Prayer of Confession (9:1–38)

On the twenty-fourth day of the same month (9:1). The text as it stands refers to events that occurred two days after the end of the Feast of Booths, which took place from Tishri 15 to 22. According to Leviticus 16:29, Tishri 10 was the great Yom Kippur or Day of Atonement, on which every man searched his own heart. Though not held on the tenth day, this day of penance resembles the spirit of the Day of Atonement.

M. Gilbert in a perceptive analysis highlights several keys to this confessional prayer. He notes that the giving generosity of Yahweh is stressed by the occurrence of the verb nātan (“to give”) fourteen times: “He gives the land, the Law, the manna, water, his Spirit, the oppressors, but also the deliverers…. No biblical text, it seems, uses so frequently the verb ‘to give.’ ”237 He also observes that another theme is the land (hā-ʾāreṣ), which occurs thirteen times. He observes that Yahweh is addressed directly as “you” (ʾattâ) ten times.

This prayer of confession has been compared to Psalm 136 and to the apocryphal “Prayer of Manasseh,” the wicked king who reigned fifty-five years (2 Kings 21:1–18; 2 Chron. 33:1–20). This short prayer, which is not included in Catholic versions of the Bible such as the NAB and JB, has been called by Bruce Metzger “one of the finest pieces in the Apocrypha.”238 Blenkinsopp has called attention to a somewhat similar text from Qumran entitled “The Words of the Heavenly Lights,”239 which were prayers for the days of the week. These also recall God’s mercy in creation and in history, confess Israel’s rebelliousness, and ask for forgiveness. They speak as well of Moses having atoned for their sin.240

Wearing sackcloth and having dust on their heads (9:1). “Sackcloth” (śaq) was a goat-hair garment that covered the bare loins during times of mourning and penance. “Dust” (ʾ adāmâ) occurs 221 times in the Old Testament. It originally indicated reddish-brown earth. Joshua 7:6; Lamentations 2:10; and Ezekiel 27:30 also mention the placing of ʿāpār (“ashes,” often rendered “dust”) on one’s head (cf. also 2 Sam. 13:19; Job 2:12). At the excavations at Beersheba in 1970–71, Anson F. Rainey noticed that the streets were composed of gray ash made from the broom tree. The mourner could simply sit on the ground and pick up ashes and dust to place on his head, which was a sign of mourning (1 Sam. 4:12; 2 Sam. 1:2; 15:32).241

Levites (9:5). According to the Hebrew text, this prayer is ascribed to the Levites. The RSV and NRSV insert at the beginning of verse 6: “And Ezra said,” following the LXX. In any case, this is one of the most beautiful and most complete liturgical prayers outside Psalms (cf. Ps. 78; 105; 106). The prayer reviews God’s grace and power in creation (Neh. 9:6), in Egypt and at the Red Sea (vv. 9–11), in the desert and at Sinai (vv. 12–21), during the conquest of Canaan (vv. 22–25), through the judges (vv. 26–28), through the prophets (vv. 29–31), and in the present situation (vv. 32–37). Allen comments, “Verses 6–25 presented kaleidoscopic pictures of divine grace: common grace, prevenient grace, and forgiving grace.”242 The prayer in Nehemiah 9:5–37 has had a profound impact on the Jewish synagogue service243 (see sidebar on “Synagogues”).

You alone are the LORD (9:6). This beginning affirmation, though not in the same words as the famous Shema of Deuteronomy 6:4, expresses the central monotheistic conviction of Israel’s faith (cf. 2 Kings 19:15; Ps. 86:10; Isa. 37:16). The concept of a singular God, which both Christianity and Islam have derived from Judaism, was exceptional in antiquity. Except for the abortive monotheism of Akhnaton in Egypt (c. 1350 B.C.),244 the Greek philosopher Xenophanes (560–478 B.C.), and the questionable case of Zoroastrianism,245 the religions of ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Canaan, Greece, and Rome were all uniformly polytheistic.

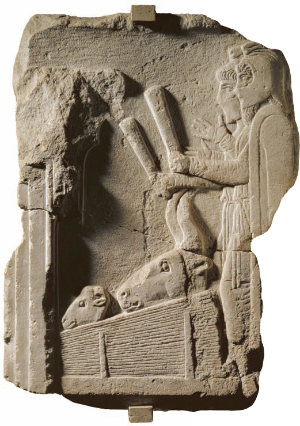

All their starry host (9:6). “Host” (ṣābā ʾ (pl. ṣebā ʾôt) literally means “army, host, warriors.” The NIV interprets the host here as stars (cf. Gen. 2:1). The ancients worshiped the stars and the planets, a practice forbidden in the Torah (Deut. 17:3). The observation of celestial phenomena by the ancient Mesopotamians led to the development of astrology.246 But the word can also mean angels (cf. 1 Kings 22:19; Ps. 103:20–21; 148:2). Elsewhere the KJV transliterates the word in the phrase “the Lord of Sabaoth,” which means “the Lord of hosts.” The expression, which occurs three hundred times in the Old Testament, is especially prominent in the prophetic books of this period, occurring fourteen times in Haggai, fifty-three in Zechariah, and twenty-four in Malachi.

Astrology was developed to new levels and practiced intensely by the Magi. This 5th century B.C. relief of two magi with their bundles of reeds is from Daskyleion (Ergili, Turkey).

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, courtesy of the Istanbul Archaeological Museum

Image of a calf (9:18). The “image of a calf” recalls Exodus 32:4–8 and Deuteronomy 9:16. The Egyptians worshiped their gods in animal form. The Apis bull of Memphis represented the god Ptah, and the cow the goddess Hathor.247 Jeroboam I, who erected golden calves at Dan and Bethel in leading the ten northern tribes in rebellion against Solomon’s son, Rehoboam, was no doubt influenced by the time that he had spent as an exile in Egypt.

Your great compassion (9:19). “Compassion” renders raḥamîm, which is a cognate of reḥem (“womb”). Girdlestone says that this “expresses a deep and tender feeling of compassion, such as is aroused by the sight of weakness or suffering in those that are dear to us or need our help” (cf. also 1:11; 9:27–28, 31).248 The two adjectives that describe Allah as “merciful and compassionate” in the opening lines of the Qurʾan are cognate Arabic words (raḥmîn, raḥem).249

Sihon king of Heshbon (9:22). Sihon refused the Israelites passage through his land, which was in Transjordan between the Jabbok and the Arnon (Num. 21:21–33; Deut. 2–3; Judg. 11:19–21, Ps. 135:11; 136:19–20). Excavations between 1968 and 1971 at Tel Hesban have not revealed any settlements earlier than the seventh century B.C., so the location of Sihon’s Heshbon remains uncertain.250

Wells already dug (9:25). The lack of rainfall during much of the year made it necessary for almost every house to have its own well or cistern to store water from the rainy seasons (2 Kings 18:31; Prov. 5:15).251 By 1200 B.C. the technique of waterproofing cisterns was developed, permitting the greater occupation of the central Judean hills.252

Iron Age well rebuilt by Romans

Kim Walton

Kings of Assyria (9:32). One of the “kings of Assyria” was Shalmaneser III (858–824 B.C.), who reported that he defeated Ahab at the important battle of Qarqar in 853, an important battle not mentioned in the Old Testament.253 The first Assyrian king to expand his empire to the Mediterranean was the great Tiglath-Pileser III, also known as Pul. He attacked Phoenicia in 736, Philistia in 734, and Damascus in 732.254 Early in his reign (752–742) Menahem of Israel paid tribute to him (2 Kings 15:19–20).255 During his campaigns against Damascus, he also ravaged Gilead and Galilee and destroyed Hazor and Megiddo (2 Kings 15:29).256

Shalmaneser V (727–722 B.C.) laid siege to Samaria—a task completed by Sargon II (721–705).257 Sargon’s commander carried on operations against Ashdod (Isa. 20:1). Sennacherib (704–681) failed to take Jerusalem in 701 (2 Kings 18:13–17) but captured Lachish.258 Esarhaddon (681–669) conquered Lower Egypt259 and extracted tribute from Manasseh of Judah (2 Kings 19:37; Ezra 4:2; Isa. 37:38). Ashurbanipal (669–633) also invaded Egypt and proceeded as far south as Thebes.260 He was probably the king who freed Manasseh from exile and restored him as a puppet king (2 Chron. 33:13; Ezra 4:9).261

They rule over our bodies (9:37). The term gewiyyâ (“bodies”), used thirteen times in the Old Testament, characterizes the human being in weakness, oppression, or trouble (e.g., Gen. 47:18–19). It is also used of a “corpse” (1 Sam. 31:10, 12; Ps. 110:6; Nah. 3:3) or of a “carcass” (Judg. 14:8–9). The Persian rulers drafted their subjects into military service. Possibly some Jews accompanied Xerxes on his invasion of Greece.

Making a binding agreement (9:38). “Making” is literally “cutting.”262 “A binding agreement” translates ʾ amānâ, which occurs only here and in 11:23, where it means a “royal prescription.” The word is related to “Amen,” and its root has the connotation of constancy. The KJV and RV translate it “sure covenant.” The usual word for covenant (berît) appears in 1:5; 9:8, 32; 13:29; and in Ezra 10:3. The Old Aramaic inscription of Panammu I, dated to the eighth century B.C., has a similar expression: mn krt (“a sure covenant struck”).263