Haman’s Plot to Destroy the Jews (3:1–15)

Haman … the Agagite (3:1). The name Haman, as well as that of his father, are Persian, though their meanings are disputed. The most plausible explanations are that Haman is a Hebraized form of the name that appears in classical sources as Omanes, and that Omanes is a form of the name “Humpan,” an Elamite deity.105 The term “Agagite” is rendered as a gentilic noun, that is, an indication of ethnic origin. Ancient interpreters universally understood the text to mean that Haman was a member of the race of Agag, or the Amalekites.106 The Amalekites were a nomadic people descended from Esau (Gen. 36:12, 16). They typically ranged through the Negev and Sinai Peninsula, where they clashed with Israel during the Exodus (Ex. 17:8–13; Deut. 25:17–18). But during the reign of King Saul, the conflict became fateful. God ordered Saul to utterly destroy the Amalekites and to take no booty from them. But Saul saved some of the loot and took the Amalekite king, Agag, as a captive. The prophet Samuel killed Agag, but not before informing Saul that his disobedience would cost him his throne (1 Sam. 15). Since Mordecai is associated with the house of Saul, the clash between Mordecai and Haman is set up as a “rematch” of the Saul–Agag affair.

Higher than … all the other nobles (3:1). The exact nature of Haman’s position is not explicit in the text. Since he was not native Persian, he was not from one of the seven noble families that served as advisors to the king. Modern writers frequently call him Xerxes’ “vizier” or “prime minister,” but it is uncertain that the Achaemenid court had such a position.107 Another possibility is that he held the position of hazarpatish, or “Commander of the Thousand” (called the “chiliarch” by the Greeks). This officer was the head of the king’s personal bodyguard, and no one could enter the king’s presence without his permission. The Greeks believed the chiliarch was the second great power of the kingdom, but they probably formed a mistaken impression based on the officer’s easy access to the throne. Persian sources do not seem to attribute a great deal of authority to the position.108 It has also been suggested that Haman held the office that the Greeks called the “King’s Eye,” an inspector who had charge over all the satraps.109 It would have been a position of great authority and economic influence; but once again, Persian evidence for the existence of such an office is scant.110

Kneel down (3:2). According to Herodotus, the Persians were very conscious of social class, observing strict protocols.111 They would greet equals with a kiss, but would always bow and make obeisance before those of higher standing. Such prostrations were foreign to the Greeks but common throughout the Near East. Ancient Near Eastern peoples often knelt before one another as a sign of respect. Israelites generally had no qualms with such demonstrations (see, e.g., Gen. 33:3; 42:6; 1 Sam. 20:41; 24:8). Given that prostration was such a common sign of respect, Mordecai’s refusal to kneel down or pay Haman honor (3:3) is a mystery. The rabbis invented a story that Haman carried an idol with him, and it was before this image that Mordecai refused to bow.112 But this story was moralistic rather than historical, with no textual support. A more likely explanation may be found in Mordecai’s assertion that he will not bow to Haman because he (Mordecai) is a Jew (3:4). It is probably ethnic antagonism between Jews and Amalekites that lies behind Mordecai’s refusal to pay Haman the required homage.

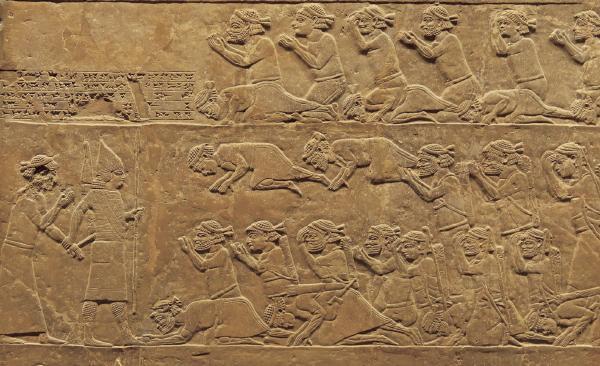

People bowing before a ruler

Todd Bolen/www.BiblePlaces.com

Killing only Mordecai (3:5). Most civilizations of the ancient Near East adhered to the notion of lex talionis, or “proportional retribution.” A person was only allowed to respond to an injury with an injury equal to that received: an eye for an eye, or a tooth for a tooth. This idea is found in the law code of Hammurabi §190, as well as in the Old Testament (Ex. 21:15; Lev. 24:17–22). Haman’s plan to punish the entire Israelite nation because one man wounded his pride was excessive. But there is poetic justice in Haman’s evil design. Israel had been commanded to utterly exterminate the Amalekites (Deut. 25:17–19; 1 Sam. 15:3); now, an Amalekite attempts to exterminate Israel.

Nisan (3:7). March-April (see comments on 2:16). In Babylonian thought, the opening days of the new year was the time when the gods determined mortal destinies. This ancient tradition may have made the beginning of the year seem an especially appropriate time for Haman to determine the date for the Jews’ destruction.

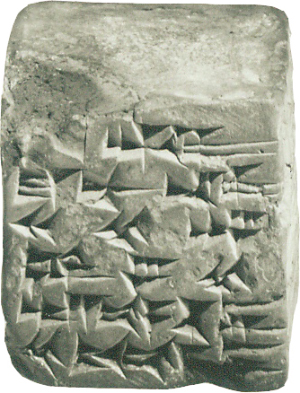

Lot of Yahali, 9th c. B.C. using the word puru for the lot

Courtesy of the Yale Babylonian Collection

Pur (3:7). The word pur is the Babylonian word for a lot, and Esther’s author provides the Hebrew translation for his readers, who would be unfamiliar with the term.113 The casting of lots was a common method for determining the will of the gods or deciding any matter of great importance. In the Old Testament, lots were used frequently in cases where choices were needed—for example, to select the scapegoat on the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16:8) or to identify God’s chosen king (1 Sam. 10:20–21). Herodotus and Xenophon attest to the use of lots in Persia.114

The form of the lot and how it was used are uncertain. One possibility is that the lot was cast onto a surface that was divided into sections marked with the names of the months and days. The day on which the lot fell would be considered the gods’ choice. Another possibility is that lots with months and days printed on them would be placed inside a pouch. The pouch would be shaken until one of the lots popped out, thus indicating that a god had chosen that particular date.115 An Assyrian lot from the ninth century B.C. has been recovered; it is a baked clay square about an inch across, inscribed with a prayer.116

Customs are different … do not obey the king’s laws (3:8). The same Hebrew word is translated here as “customs” and “laws” (dāt). The Persians regularly allowed subject peoples to follow their own laws and customs, so long as these did not interfere with the peace of the empire.117 The Jews did, indeed, have unique customs, such as keeping the Sabbath and eating kosher foods, but these presented no danger to Xerxes. More troublesome was the charge that the Jews would not obey the king—that is, they were rebellious (cf. Ezra 4:14–15). Xerxes had dealt with the revolt in Egypt in the first year of his reign (485 B.C.),118 and he ferociously suppressed revolts in Babylon in 484 and 482 B.C. In the course of this action, Xerxes showed none of the mollifying tendencies for which Cyrus had been famous.119 He had no compunctions about using ruthless tactics to secure the compliance of his subjects.

Decree … to destroy them (3:9). The idea of genocide seems especially repugnant to us in the light of atrocities committed against the native Americans and the Jewish Holocaust. But in the ancient world, genocide was not considered abhorrent. Indeed, the thirteenth-century Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah bragged (rather prematurely) that he had utterly destroy the Israelites, leaving them no descendants.120 Among the Persians, too, there is evidence of such excessiveness. In 522 B.C., when Darius overthrew a Magian who had seized the throne of Persia, the Persians went on a rampage, slaughtering all the Magians they could find. Herodotus reports that only nightfall prevented their extinction.121

Ten thousand talents of silver (3:9). Haman is apparently offering a bribe, promising to provide the royal treasury with a sum far above what is needed to exterminate the Jews. Of course, bribery is a perennial problem of any government, but it seems to have been especially troublesome in Persia. The Greek writer Xenophon (ca. 430–355 B.C.) reports that in Persian courts, the decision went to whichever party provided the largest bribe.122 Alternatively, Haman’s offer has been explained as an example of the ancient, acceptable custom of bakshish: offering a gift in exchange for a favor.123

The size of the bribe that Haman offered was fantastic. According to the standard established by King Darius, it equaled about 333 tons of silver. At the time of this writing, silver sells for over $6.00 per ounce, making this bribe worth about $64 million. But a better way to understand the size of Haman’s bribe is to compare it to the actual resources of the Persian Empire at the time. Based on the figures given in Herodotus, Haman’s bribe has been estimated to equal about two-thirds of Persia’s annual revenue.124

Signet ring (3:10). The signet ring served like a signature in the ancient world. One would place wax or other substances on the document to be sealed, and then press the signet ring into the sealing material, making a unique impression that could be recognized and identified by the signet’s owner, or by others familiar with the design. The rings were usually made of gold or precious stones, and gold signet rings have been excavated from Persepolis.125 In this era, however, the Persians seemed to have preferred using cylinder seals for official communications. These objects were worn around the neck on a string, placed on a spindle, and rolled in the sealing material.126

Egyptian god signet ring portraying pharaoh before Hathor

Rama/Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Louvre

Keep the money (3:11). The Hebrew reads literally, “The money is given to you.” Many translators follow the LXX in understanding that Xerxes told Haman that the king would fund the Jews’ destruction himself rather than accepting Haman’s offer of silver. But since Mordecai states later that Haman’s promised funds would go into the royal treasury (4:7), the Hebrew reading seems preferable. The expression probably means that Haman had sufficient funds to do as he had said. It is uncertain where these funds would have come from. If they were his personal funds, they represented a vast fortune. Another possibility is that Haman’s position gave him authority over certain public monies, and Xerxes granted him permission to use those funds for the task at hand. Or, perhaps Haman was anticipating a great deal of spoil from the destruction of the Jews, and he intended to use those funds to pay off his mercenaries.

Xerxes’ condemnation of the Jews on Haman’s testimony violated a principle of Persian law forbidding anyone to be executed on the testimony of a single witness.127 Herodotus expresses his admiration for this principle, and Xerxes himself proclaimed his fairness in the so-called “harem inscription” found at Persepolis, stating that he would never render a judgment in a case until he had heard the testimony of both parties.128

On the thirteenth day of the first month (3:12). That is, the day before the Jews were to celebrate Passover (see comments on 3:7).

Script of each province … language of each people (3:12). See comments on 1:22.