Chapter 6

Triangle Offense

Phil Jackson and Tex Winter

Tex and I have been coaching together since 1989, when I became head coach of the Chicago Bulls and he remained with the organization as an assistant. Tex is an original thinker about basketball and has played an invaluable role in establishing a system of play and coordinating our efforts on the offensive end of the court.

This system is much more than a series of plays—it’s a philosophy, a consistent way of thinking and executing that kicks in each time we gain possession of the ball. In the transition from defense to offense, players move in a natural, purposeful flow so that we’re in position and rhythm when we bring the ball into the half-court.

Over the years, this style of play has been called the triangle offense, the triple-post offense, and the sideline triangle offense. Tex doesn’t claim to have invented it, but he has mastered teaching it and instituting it, not simply as a sequence of movements but rather a set of concepts and rules that guides an offensive attack.

To describe it, we would say this offense is a sideline triangle on one side of the court and a two-man game on the other side, in which the offensive options are dictated by the positioning and reactions of the defenders. But it really isn’t all that complex. In fact, the triangle—the label we’ll use for brevity’s sake—is an offensive system that can be applied to all levels of competition.

It is old-school basketball in that it’s founded on the basics: exact court spacing, execution of fundamentals, and constant movement of ball and players based on certain rules. Winning requires a five-man coordinated effort, and we get that when we get our teams to run it properly.

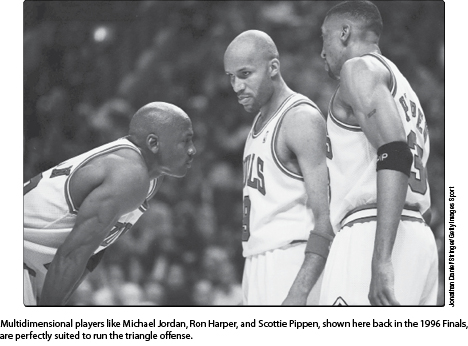

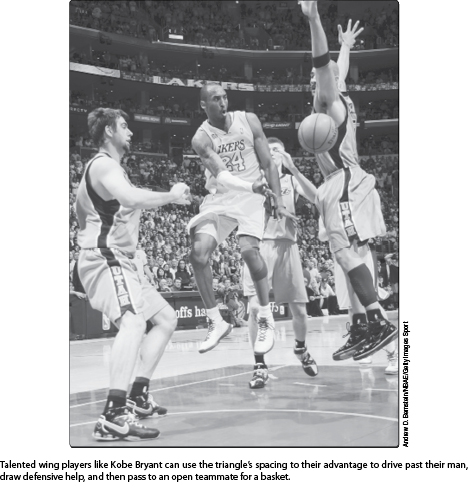

The primary misconception about the offense is that it is designed around a gifted player. Yes, Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Shaquille O’Neal, and Kobe Bryant have thrived in the system, but those four all-time greats would excel and score in any system. What the triangle really does is help players who aren’t so gifted contribute to a team’s success at the offensive end. The system, or method of play, as Coach Winter likes to call it, uniquely offers an offense the option to play unselfishly as a unit while still allowing players creative individuality in their offensive decisions.

The triangle offense requires players to be self-reliant and in control of their game. The system provides a framework that frees both the athletes on the court and the coach on the sideline from having to call a particular play or isolation on numerous occasions during a game. I do not want to, nor is it best to, dictate how a Michael Jordan or a Kobe Bryant applies his amazing scoring ability one possession after another.

I’m convinced that highly structured, nonspontaneous basketball does not win championships. My belief was, and is, that a team on the floor knows best what is going on and the players must be confident that they can read the defense and react accordingly. This style of play does, however, require players to be disciplined and willing to submit their personal ambitions to the best interests of the group. This is essential for the system to achieve optimal results.

The system also runs better when players’ games are well-rounded, not one- or two-dimensional. Complete players well-versed in fundamental movement, ball handling, screening, and shooting skills will perform the tasks demanded of them within the offense more effectively and consistently. Basketball played at its best is a reflexive sport, and I want my team to play a fluid, instinctive, complete game.

I rejected the idea of relying solely on a point guard to bring the ball up the court and make all the ball-handling decisions. Ultimately, a good defensive opponent will pressure and destroy a team with a single point-guard orientation. A two-guard offense allows players to share the ball handling and passing duties and prevents a defense from ganging up against one player out front.

Seven Principles of the Sound Offense

An effective offense, to my way of thinking, features the following dimensions.

1. Penetration. Players must penetrate the defense, and the best way to do this is the fast break, because basketball is a full-court game, from baseline to baseline.

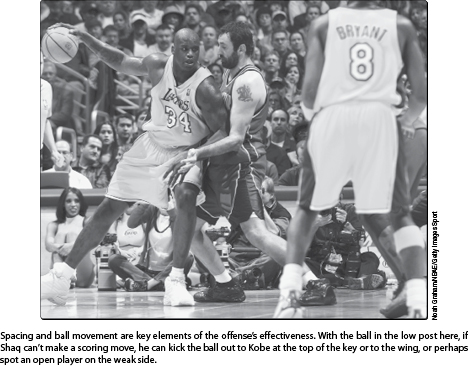

2. Spacing. I am a fanatic about how players distribute themselves on the offensive end of the court. They must space themselves in a way that makes it most difficult to defend, trap, and help. Players must align a certain number of feet apart. In high school, I’d recommend 12 to 15 feet spacing, in college, 15 to18 feet, and in the NBA, 15 to 20 feet. Proper spacing not only exposes individual defensive players’ vulnerabilities, but also ensures that every time the defense tries to trap, an offensive player will be open.

3. Ball and player movements. Players must move, and must move the ball, with a purpose. Effective off-the-ball activity is much more important than most fans and players think because they’re so used to watching only the movement of the ball and the player in possession of it. But there is only one ball and there are five players, meaning most players will have the ball in their hands 20 percent or less of the time the team is in possession of the ball.

4. Options for the ball handler. The more options a smart player has to attack a defender, the more successful that offensive player will be. When teammates are all moving to positions to free themselves (or another teammate with a pick), the ball handler’s choices are vastly increased.

5. Offensive rebounding and defensive balance. On all shots we take, players must go strong for the rebound while retaining court balance and awareness to prevent the opponent’s fast break.

6. Versatile positioning. The offense must offer to any player the chance to fill any spot on the court, independent of the player’s role. All positions should be interchangeable.

7. Use individual talents. It only makes sense for an offense to allow a team to take advantage of the skill sets of its best players. This doesn’t preclude the focus on team play that is emphasized in the six other principles, but it does acknowledge that some individuals have certain types and degrees of talent, and an offense should accentuate those assets. Michael Jordan taught me this.

Finally, I want the offense to flow from rebound to fast break, to quick offense, to a system of offense. The defenses in the NBA are so good because the players are so big, quick, and well coached. Add the pressure that the 24-second clock rule applies to the offense to find a good shot, and the defense gets even better.

The triangle offense has proven most effective, even against such obstacles, when players commit to and execute the system. The offense hinges on players attending to minute details in executing not just plays but also the fundamentals underlying the plays. Once players have mastered the individual techniques required of their roles, we then integrate those individuals into a team. Once this is done, the foundation for a good offense is solidly in place. The team can then go on the court with the confidence and poise so essential to success.

This method of play is as old as basketball. The triangle set is adjustable to the personnel, but such adaptations can be made without altering the essence of the offense. The only necessary adjustment from one season to the next involves tailoring the series of options based on each individual’s talents. Now Tex and I will present the triangle offense in detail, including some of those variations and options to optimize its use for specific teams.

Court Symmetry

Proper spacing gives the ball handler ample room to respond to help and traps and also puts the onus on the defense to cover a larger area in which it can be attacked at more angles. So the offense starts in a symmetrical alignment of players, forming a triangle on both sides of the half-court (figure 6.1).

In the triangle offense, the role of the players is totally interchangeable. There’s no need for the guards, forwards, and centers to play only in their typical spots on the floor—the spots can be filled by any player. Once the spots are filled, the offense is run by where the ball is positioned on the court and by how the defense is moving.

Line of Deployment

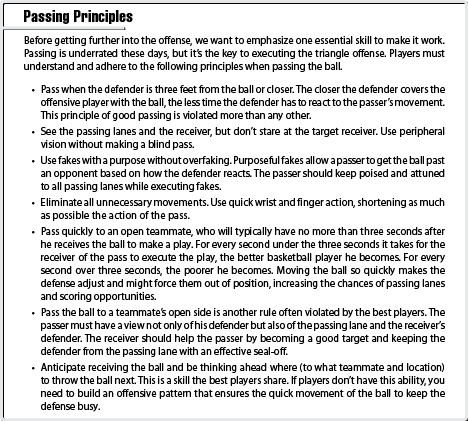

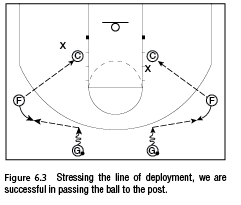

One of the assets of the triangle offense is the chance to isolate the post and attack his defender. We want to talk now of the “line of deployment,” a basic concept. With this term we mean an imaginary line traced from the forward with the ball to the center in the low post, his defender, and the basket.

To play a standard defensive position between the center and the basket, the defender of the center must play behind him, as long as the center remains on the line of deployment (figure 6.2). But when being defended in this way, it’s easy for the forward to pass the ball to the center.

If the center’s defender wants to prevent an easy pass, he must overplay him, either on the baseline side or the high side, losing in this way his alignment with the center and the basket, so the forward can make a quick pass to the open side of the center. The center must master the technique of shaping up on the post, playing the line of deployment. After receiving the pass, the center can either shoot or pass out to a teammate in position to do something constructive with the ball (figure 6.3).

By thoroughly indoctrinating the players on the line of deployment theory, we feel we have been successful in getting the ball to our center, and this has been true despite a concentrated effort by opponents to prevent the pass to the post.

Forming the Sideline Triangle

Most offenses require an entry pass to start a play, but this is not the case with the triangle offense. The triangle offense can be initiated with any of several pass options, depending on defensive adjustments and offensive strategies.

First Pass (Strong-Side Fill)

Following are the options for the first pass, strong-side fill.

Guard to Wing

• Outside cut. The ball handler (1) dribbles in the pro lane, passes to the wing (3), cuts outside him, and goes to the corner, forming a triangle with 5 and 3. Here we must again talk about spacing—3 must set himself at a proper distance away from the sideline to let 1 cut behind him (as well as to allow the other types of cuts, which we’ll explain soon).

• Slice cut. 1 passes the ball to 3, moves toward him, and then cuts away and goes to the corner (figure 6.4).

• Blur screen cut. 1 passes the ball to 3, cuts inside, brushes off the center (5), and moves to the corner.

• Basket cut. 1 passes the ball to 3 and then cuts to the basket, coming off 5 and moving to the corner (figure 6.5).

On all the cuts of the strong-side guard (1), the other guard (2) moves to the middle of the floor for defensive balance and then plays two on two on the weak side.

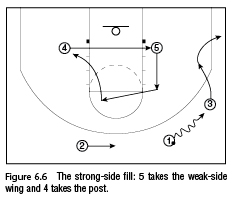

Wing Dribble Entry

1 dribbles toward 3, which signals 3 to go to the basket and then to the corner; meanwhile, 5 moves to the high post, and 2 goes to the middle of the court. Then 4 cuts into the lane and takes the center position, while 5 replaces 4 in the wing spot with a weak-side cut (figure 6.6).

Center Corner Fill

• 1 passes to 3; 5 goes to the corner; 4 cuts, high or low, into the lane and replaces the center; and 2 cuts to the weak-side wing spot, replacing 4 (figure 6.7). 1 moves to the top of the circle, and proper spacing is maintained.

• Another option: 1 passes to 3, 5 goes to the corner, and 1 (or 2, whichever is the better post player) replaces 5 in the post (figure 6.8).

First Pass (Weak-Side Fill)

Following are the options for the first pass, weak-side fill.

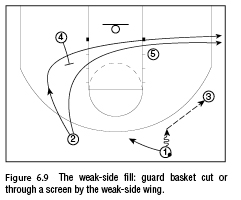

Weak-Side Guard Fill

1 passes to 3; the weak-side guard (2) can then fill the corner in two ways (figure 6.9):

• with a basket speed cut, or

• after a back-pick off the wing (4).

Weak-Side Forward Fill

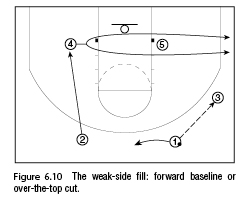

1 passes to 3; 4 makes a baseline or over-the-top cut and fills the corner; 2 replaces 4 in the wing position (figure 6.10). Note that the court is once again balanced.

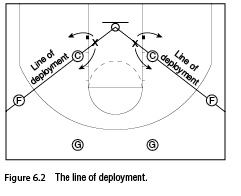

Second Pass

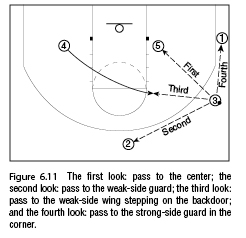

After we form the triangle on the strong side of the court, four passes could become available for the strong-side wing. We call these four passing options “second pass” because they’re made after the first pass to the wing position, which initiates the offense. There are four spots on the court where these passes could be directed, and each of these spots offers a multitude of offensive options.

Assuming that 1 passes to 3 and then fills the corner, 3 reads the defense and takes the following looks to pass (figure 6.11):

First look: to the center (5).

Second look: to the weak-side guard (2) at the middle of the half-court at the top of the circle.

Third look: to the weak-side wing (4) on the backdoor step.

Fourth look: to the strong-side guard (1) in the corner.

First Look: Pass to the Center

We’ll now show one of the simplest options of this offense; it’s as old as basketball, but still quite effective. It’s called split cuts or split the post or sometimes post cuts. The play starts with the entry pass from 1 to 3 and 1’s outside cut to the corner to form the sideline triangle, while 2 goes to the middle of the court (figure 6.12).

Option 1. 3 passes to 5, makes a fake to cut inside the lane, and then cuts on the baseline side of 5 while 1 cuts as close as possible behind 3. The passer is the first cutter and cuts to the side of the teammate he is trying to free (5) (figure 6.13).

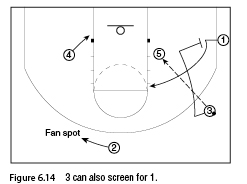

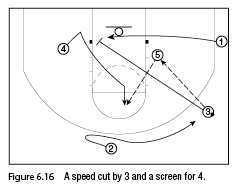

3 can also make a change-of-pace cut and attempt a screen for 1 (figure 6.14). 2 spots up opposite to the ball at the fan spot, and 4 gets near the lane for the rebound. After the pass to the post (5), 3 can also start a speed cut and then screen for 2 (figure 6.15). 3 might also make a speed cut and then screen for 4, while 1 speed cuts on the baseline (figure 6.16).

The post (5) can also kick the ball off to 2, who has spotted up on the weak side at the fan spot, also called the garden spot because it’s a nice and open spot on a court for shooting if the defensive man attempts to double team the center (figure 6.17).

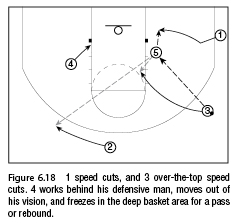

Option 2. 3 passes the ball to 5; 1 speed cuts to the baseline and, if open, receives a drop pass from 5; 3 makes an over-the-top speed cut (we call this an action zone speed cut). Meanwhile, on the pass from 3 to 5, 2 spots up at the garden spot to receive the ball from 5, and 4 cuts behind the defense to the freeze spot (figure 6.18). The freeze spot is a point on the court where he keeps his defender busy while waiting for a possible screen.

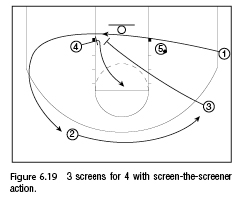

If 1, 2, or 3 aren’t open, 1 continues his cut, rubs off 4’s screen, and moves out for defensive balance, while 3 cuts into the lane and screens for 4 (screen-the-screener action) and 2 replaces 3 (figure 6.19). 4 pops out to the free-throw area and receives the ball from 5, or, if 4 is not free, 5 can also pass to 3, who has rolled to the basket after the screen. If he has no other choice, 5 can pass to 2. If 3 doesn’t receive from 5, he fills the corner on the weak side (figure 6.20).

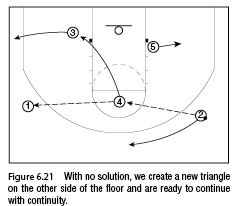

2 passes to 4 (or can pass back to 5) and then moves to the top of the circle. If 4 is not free for a shot, he passes to 1 and then cuts to the low-post position, while 5 takes the weak-side wing spot (figure 6.21). Now we have formed the triangle on the other side of the floor, and we can restart our offense. As we like to say, “We are always in our offense and ready to operate!”

Option 3. After the pass to 5, 3 makes a rebound screen cut (starting to cut as if going to the rebound in the lane, but instead going to screen), while 1 step fakes on the baseline to set the defender up and cuts off 3’s screen to a position in front of 5; 2 and 4 spot up opposite to the ball (figure 6.22). 5 passes the ball to 2 or 4, whichever one is open.

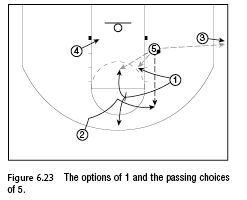

If neither 2 nor 4 is open, 1 continues to the free-throw line area, where he can cut into the lane, screen for 2, who has come back to the ball, and then roll to the basket or pop out after the screen (figure 6.23). 5 can pass to 1, 2, or 3, who, after setting the screen, pops out in the corner.

Second Look: Pass to the Weak-Side Guard on Top of the Circle

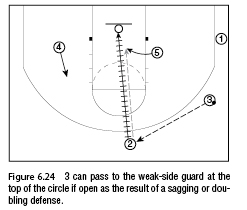

Option 1. If 5 is not open, 3 can pass to 2 at the top of the circle; if 2 is open, 2 can shoot as the first option, or pass to 5, who ducks into the lane (figure 6.24).

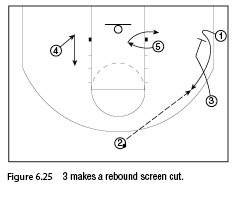

If 5 is not open on his duck into the lane, 3, after the pass to 2, runs a rebound screen cut, while 1 step fakes on the baseline to set the defender up and cuts off 3’s screen on the way back to defensive balance. 2 can pass to 1 if he’s open (figure 6.25). 4 fakes a cut and comes back, as does 5. This action keeps the defense occupied off the ball.

2 can pass to 1 if he’s open, or, if the defense is sagging, can dribble weave the ball to 1. 2 passes to 1 on the dribble interchange, at about the midpoint, or 2 passes up to 1 and 1 passes to 3, who has stepped back into the corner after the screen (figure 6.26). 4 reverses back to the basket area as the dribble-weave action takes place to get into rebounding position, and 5 posts deep or rebounds if a shot goes up.

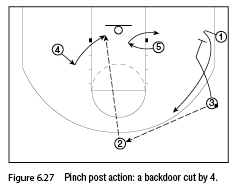

Option 2. We call this play pinch post action. 4 starts to pop out to the ball when 2 receives the ball from 3, but 4 is overplayed, so he reverses to the basket (in a backdoor cut) to receive an over-the-top pass from 2; meanwhile, 1 gets back for defensive balance, and 5 keeps his defender busy, moving in and out of the lane ready to rebound or freeze at the basket for a pass (figure 6.27). 2 passes to 4.

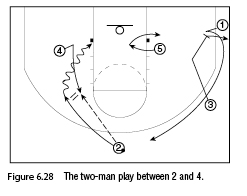

If 4 can’t receive on the back door, he pops out to the high-side post area at the elbow and receives the ball from 2, who speed cuts off 4 and receives the ball back via a short flip pass off 4’s front hip (figure 6.28). 2 must have his hands in a ready position to catch the ball on the two-man play, while 3 screens for 1. After the screen, 3 steps back to the corner, 1 moves back for defensive balance, and 5 keeps his defender busy and then freezes for a second at the block.

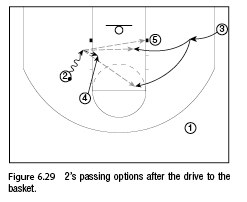

2 drives to the basket, and 4 reverse pivots with the pass—he opens up to the ball, reads the defense, and reacts accordingly. If there’s a direct line to the basket, he dive cuts to the basket and receives a return pass from 2. If 2 is double teamed, 4 opens up to the ball with a reverse pivot and holds for a return pass from 2 (figure 6.29). 5 freezes at the block, ready to receive a possible pass from 2, and 3 spots up for a possible kickoff pass or cuts to the front of the rim for a pass or to go after a rebound.

Third Look: Pass to the Weak-Side Wing on the Backdoor Step

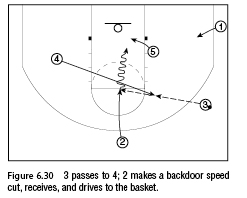

Option 1. 3 passes to 4, who has flashed to the elbow on the ball-side high post, and 2 makes a backdoor speed cut to the basket. If 2’s head and shoulders are by his defender, 4 makes a quick drop pass to 2 (figure 6.30). 2 should reach ahead for the ball, catching it knee-high.

3, after making the pass to 4, runs a rebound screen cut, while 1 step fakes to the baseline and comes off the screen of 3. 1 gets back for defensive balance, and 3 reads the play and prepares for the rebound off the front of the rim. 5 freezes at the block and anticipates a possible pass from 2, in case his defender switches to help 2’s defender on the drive (figure 6.31). 4 then reverse pivots and reads the defense, staying behind the ball or diving to the basket, ready to receive a pass from 2 if 4’s defender drops to cover 2.

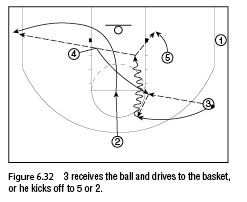

Option 2. 3 passes to 4, who has flashed to the elbow on the ball-side high post, and 2 makes a backdoor speed cut to the basket. If 2 is not open, he cuts into the corner, and 3 cuts right after him to receive a pass from 4 (figure 6.32). 3 can drive to the basket for a layup, or he can drive and kick off to 5 on the block, or to 2, who spots up in the corner.

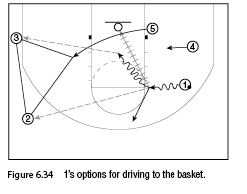

If 2 is not open and 3 can’t receive the ball, 4 dribble weaves to 1 coming out of the corner, or passes to him on the step back to the corner (figure 6.33). If 1 receives the ball on the dribble weave, he drives straight to the basket, or he can take a jump shot or make a fan pass to 2 or 3, spotted up at the wing and in the corner, while 5 flashes to the low post from the other side of the floor (figure 6.34).

If nothing happens with the pass to 2, we have formed a triangle on the other side of the court with 2, 5, and 3, with 1 at the top of the lane and 4 on the weak-side wing spot, and we create continuity in our offense.

Fourth Look: Pass to the Strong-Side Guard in the Corner

3 passes to 1 in the corner, and 1 looks at the basket with a threat to shoot. After the pass, 3 makes a banana cut to the basket and can try to receive the ball, while 5 gets to the high post at the ball-side elbow (figure 6.35).

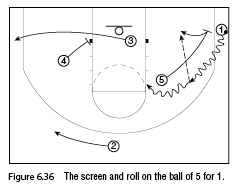

Right after 3’s cut, 5 screens and rolls on 1, who drives to the top of the key, where he can pass to 5 on the roll; 3 continues his cut and is screened by 4 on the weak side (figure 6.36); 2 fans away as 1 dribbles out of the corner, spotting up opposite to the ball.

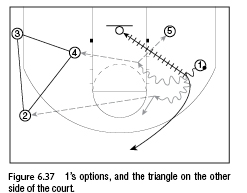

1 can shoot or drive to the basket or pass to 2, who has spotted up (figure 6.37). 1 can also pass to 4 or 5 if there’s help on the basket penetration. If nothing happens, we have formed the triangle on the other side with 3, 4, and 2, while 5 becomes the weak-side wing and 1 sets up at the top of the lane.

Solo Cut Series of Options

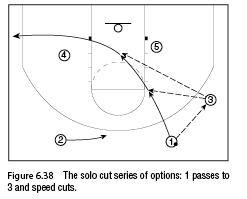

After 1’s pass to 3, instead of cutting to the corner to create the triangle, 1 makes a speed cut to receive the ball at the free-throw line area or under the basket, if he’s free (figure 6.38). 4 moves to 15 to 18 feet from the basket and holds; 2 gets to the top of the circle and holds.

3 gets into triple-threat position and looks to the post (5) for a pass. 1 holds position in the corner opposite the ball. 3 passes to 5 and makes what we call a solo cut to either side of 5 (figure 6.39). 2 spots up on the garden spot, away from the ball, while 4 screens down for 1, and 1 pops out in the corner.

As 3 cuts by 5, 5 has a cleared area for a shot, and 2 works behind the sweet spot. 3, if he doesn’t receive the ball on the cut, screens for 4, who can come high to the free-throw line area or cut to the basket to receive the ball from 5 (figure 6.40). 5 can instead pass to 2.

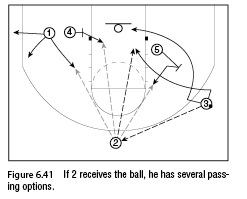

Let’s now assume that 3 can’t pass to 5. 3 then passes to 2 at the top of the circle and then makes a rub cut off 5, while 5 steps up to pinch post off 3’s cut. On the weak side, 4 screens for 1, who can pop out flat to the corner, or out and up. 2 has several options for passing (figure 6.41): He can pass to 3, 1, or 4, who has rolled to the basket after the screen for 1, or to 5 on the pinch post.

Pressure Releases

We must be able to overcome the problem of the defense, which puts a lot of pressure on our offensive players. Here we’ll show methods of pressure releases and penetrating the front-line defense.

Moment of Truth

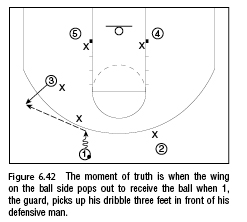

Following are some terms we use: We define “moment of truth” as the position of 3, the wing in front of the defensive player defending the ball. 1 is ready to pass the ball to the wing (3) as he reaches the moment of truth, and 3 must coordinate his pop-out so he can receive the ball at the wing position as 1 reaches the moment of truth (figure 6.42).

Therefore, we call the line of truth the imaginary line across the floor three feet in front of the defensive player guarding the ball handler (figure 6.43).

Lag Principle

If 1 reaches the moment of truth and 3 is not open on the pop out, we apply the “lag principle,” a guard-to-guard pass. 1 passes to 2 as 2 lags behind the line of truth, by three feet or more, as a safety valve. Then 2 passes to 4 as he pops out to receive the ball (figure 6.44). All three players involved in these two quick passes must coordinate their moves and timing for a successful wing entry—much dribbling is required to execute these actions properly.

Blind Pig Action

If 2, the player who should receive the lag pass, is overplayed, 4 flashes to the top of the lane, 1 passes quickly to 4, 2 speed cuts down the back side for a backdoor cut, and if he’s open receives a drop pass on the cut to the basket (figure 6.45).

If 2 is not open, he continues the cut to the weak side freeze spot, and 1 cuts over the top of 4 and receives the ball from him (figure 6.46). 1 drives to the basket or dribbles onto the operating spot, on the wing or in the corner.

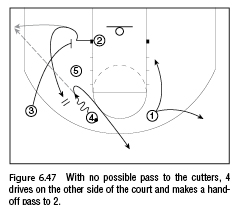

If 1 is not open on the cut, he continues to the basket area and then steps out, looks for a late pass from 4, and holds position. 4 then drives to the other side of the court for a dribble weave and meets 2 coming off the down screen set by 3 (figure 6.47). After the pass, 4 has centered the court and can operate on either side. 4 can also pass directly to 2, who has popped out to the corner after 3’s screen and fills the wing spot to form the triangle.

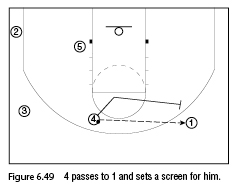

Options for 4: 4 can pass to 3 and, instead of screening for him, screen down for 1, who moves to the top of the floor (figure 6.48). 2 holds the freeze position and reads the action, while 3 holds the wing position, instead screening down for 2. If 4 goes away to screen for 1, 2 pops out to the corner area and a sideline triangle is formed by 3, 5, and 2. 4 can also pass to 1 and set a screen for him (figure 6.49).

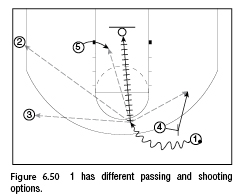

1 has the following options (figure 6.50):

• Make a drop pass to 4 on 4’s roll to the basket (screen-and-roll two-man play).

• Drive right to the basket.

• Penetrate to clear for a jump shot.

• Penetrate and pass the ball to 5 on the block; to 3, who’s holding on the weak side; or to 2 in the corner spot.

If no teammate is open, we can form the sideline triangle with 3, 5, and 2. 1 can pass to 3 and then get to the top of the circle; 4 can go to the wing spot.

After the blind pig (see figure 6.45) and 2’s cut, 4, with the ball at the top of the circle, passes it back to 1 and then goes away (figure 6.51).

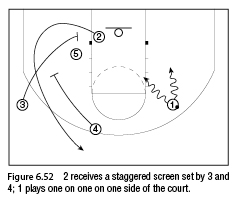

4 sets a second screen (a staggered screen) for 2, who has come out of the lane and has received a first screen from 3. 1 is isolated on one side of the court and can play one on one, while 2, if not open for a shot, has come off the screens set by 3 and 4 and is back in the center of the court for defensive balance (figure 6.52).

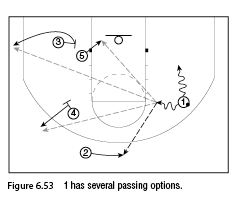

If 1 can’t beat his defender to the basket, he can pass the ball off to one of his four teammates, who have spaced out on the weak side (figure 6.53). Again, we form the sideline triangle with 4, 5, and 3, while 2 sets himself up at the top of the circle and 1 at the weak-side wing.

Wing Entry on the Blind Pig

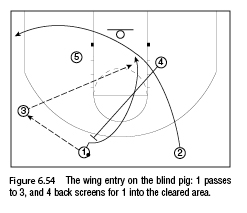

4 has flashed to the top of the circle, and 2 speed cuts into the lane and continues to the corner. But this time 1 can’t pass to 4, so he passes to 3, and then 1 receives a back screen from 4. 1 speed cuts, and 3 looks for a high over-the-top pass to 1 (figure 6.54). Note that the right side of the court is clear.

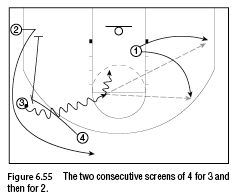

After setting the screen for 1, 4 sets a side screen for 3, who drives around 4 to the lane (we call this action wing screen and roll). 1 spots up in the corner or at the wing spot, or comes back for a dribble weave interchange with 3. After the screen for 3, 4 screens for a third time, now in the corner for 2, who comes up for defensive balance (figure 6.55). 5 freezes in the weak-side post area.

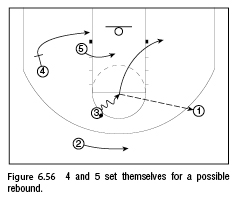

After the screen, 4 continues to the weak-side rebound position, and 3 posts down after the kickoff pass to 1 (figure 6.56). 5 sets himself in the lane to possibly rebound a shot by 1.

If 2 is overplayed or has violated the lag principle, 2 cuts first and 4 cuts second, right off 2’s tail (we call this a blur screen). 4 receives the ball from 1, 1 speed cuts off the back side of 4. 3 screens for 2, who comes up for defensive balance. 1 can also make a high pass to 2 if open (figure 6.57).

Wing Reverse

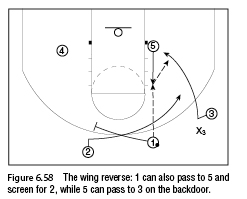

If 1 can’t pass to 2 or 3, he can pass to 5, who has flashed to the high-post position at the elbow on the ball side, as usual, respecting the spacing of his teammates. 3, on the pass to the high post (5), cuts backdoor (we call this action wing reverse). 5 drop passes the ball to 3, if 3 is head and shoulders past his defender (figure 6.58).

If 3 can’t receive the ball on the cut, 1 screens on 2 (we call this action “guard squeeze action”). 2 cuts off 1’s screen to a position three feet in front of 5, and 5 passes the ball to 2, if open. After the screen, 1 rolls to the free-throw area and can receive the ball from 5 (figure 6.59).

Final Points

Winning basketball is a matter of fundamentals and details, but you also need a tough attitude to reach the top. Players are now quicker and bigger than in the past, but this system of play, based on fundamentals, has proven effective for nearly 60 years. The system helped win college games in the 1960s and 1970s, and helped win games in the NBA during two different periods—first with the Bulls of Jordan and Pippen’s time, and second with the Lakers of Bryant and O’Neal’s time. In short, the triangle offense has proven to be ageless and tremendously effective. We hope this chapter gives you insight into basketball at a deeper level. This style of play takes basketball back to a teaching level and, at the same time, liberates players to elevate their skills at both an individual and team level. We solicit your attention to the details of the fundamental skills as the necessary tools to carry out the triangle offense. Always remember, “It’s the execution that counts.”