Chapter 7

Princeton Offense

Eddie Jordan and Pete Carril

Offensive basketball is comprised of five elements: cutting, passing, dribbling, screening, and shooting. The aim of our offensive attack is to have five players working together using each of those elements at the proper time, in the most effective manner, as the game situation dictates. These are the premises on which the Princeton offense, or high-post offense, was founded.

At Princeton University in 1967, we adopted an offensive system based on backdoor cuts, screens, and a great deal of movement without the ball. What appealed to us about this style of play was that it involved, indeed relied on, the efforts of five players, not just one or two. The offense also was very flexible and unpredictable and could be started in many ways.

The basic idea is to spread out the court with a high formation, keeping players above the free-throw area extended except when they cut to the basket. All five players are in constant motion, reading reactions of the defenders and determining the best manner of attack. This prevents the defense from providing weak-side help and leaves it vulnerable in many ways. A common result is that the defense tires over the course of a game, and we try to take great advantage of that extra step gained by the offense.

And we don’t look for just any shot. We want shots to come within the flow of players’ movements, with little or no defensive pressure, and well within the shooter’s high-percentage range.

Offensive Fundamentals

The offense is successful only when players execute with patience, poise, and unselfishness. Each offensive player must blend with his four teammates and share a mind-set and complementary skills to form a cohesive attack with multiple options. For this to happen, every player must be sound in all offensive fundamentals.

Cutting

Most of the time, the defender dictates to the offensive player which direction to cut. Is the defender denying the ball from being passed to a player? If so, the offensive player makes a backdoor cut, faking a move toward the ball or away from the basket and then quickly cutting behind the defender to create an opening through which the ball handler can pass. If the defender is playing below or slightly off the player he’s guarding, the offensive player makes a high cut to receive the pass.

When cutting in any offense, players must be aware of what their teammates are doing and try to anticipate the cuts and moves they’ll be making. If all four teammates without the ball make a basket cut or backdoor cut at the same time, a traffic jam is produced in the lane area, with no player open to receive a pass. For cuts to be effective, they must be executed with good court awareness and familiarity with teammates’ tendencies on the offensive end.

Finally, when an offensive player starts any type of cut, that cut should be completed so that the passer can anticipate where the player will be and deliver the ball with accuracy. So, even if a defender recovers to prevent a back cut from being successful, the offensive player should maintain the continuity of movement he initiated in case the ball handler has committed to the pass. If he stops in midcut to the basket and his teammate passes the ball to where it appeared he was moving, a sure turnover results.

Passing

No other facet of the game fosters offensive teamwork like quick, accurate, and unselfish passing. Conversely, a team riddled with players who dribble with no purpose and shoot low-percentage shots when they have the ball is sure to be dysfunctional.

Great passers have tremendous basketball instincts. They can see the play unfolding even at its initial stages and deliver the ball to the right spot at the right time with the right touch. The best pass isn’t made when it’s one of the few options left for the ball handler. Rather, productive passes are those that achieve a specific aim on the offense.

Not every great pass is an assist. Often it’s the pass that leads to the assist that’s more important to the score. Hockey rewards assists on such passes, and most basketball coaches value them similarly.

Passing becomes contagious when all players on a team accept the notion that the objective of an offense is to get the best possible shot on each possession. Even the best scorers on the team must subscribe to this approach. Remember that the quality of passing determines an offense’s quality of shots.

Dribbling

We want all five players on offense to be able to dribble, but we also want each one of them to use the dribble in a selective and savvy manner. Too much dribbling is nonproductive and actually stalls an offense. We ask our players to have a purpose in mind before putting the ball on the floor.

The dribble can be an effective way to create or maintain proper offensive spacing. A short dribble can create a better passing angle to a teammate. Dribbling is also one (but not the best) way to reverse the ball to the other side of the court. And just the threat of the dribble to the basket should prevent the ball handler’s defender from guarding too close for fear of getting beat for an open shot or layup.

Screening

Screens are essential for the long-term effectiveness of an offense. The best basketball programs have always used screens as a crucial part of their offensive attacks, even when isolations, one-on-one moves, and quick-shooting fast breaks became popular for a while.

Screening encourages teamwork and flow and serves to gain a specific advantage over the defense. For example, a screen on the defender of a particularly good shooter can provide that shooter the space he needs to drill a three-pointer. A screen across the lane on a post defender can open up a big man to receive a pass near the hoop for an easy basket.

Screening technique is important because ineffective screens contribute nothing to an offense and can actually diminish offensive flow through wasted time and movement and unnecessary fouls. A screen is not simply a matter of bumping and pushing a defender to help a teammate get open. In fact, good screening is an art.

Basketball is a precise sport, and screens must be executed with the same precision as a pass or a shot. Timing between the screener and the screened player is key. The screener must also determine the best angle at which to approach the defender, both to prevent the defender from fighting over the screen and to give his teammate an opportunity to get open to receive, pass, drive, or shoot the ball.

Shooting

As in passing and cutting, when a player decides to shoot he must do so, because the worst thing in shooting is indecisiveness. We want our players to shoot without unnecessary dribbling. Too much dribbling tends to make teammates stand around and watch the ball handler rather than continuing to move to get free for an open shot.

Taking and making good shots from the perimeter forces defenders to come out, and a defense that is spread across the court is much more vulnerable; it even makes smaller and slower offensive players seem taller and faster.

Players should only take shots they know they can make. Every player in the offense must have a keen sense of his individual aptitude in this regard. Indeed, knowing when not to shoot is just as important as knowing when to do so.

Initial Set

The initial set is a 2-3 alignment with two guards, two wings, and one high post (figure 7.1). When playing with a high post, you need a player in this position who’s able to pass, dribble, and shoot, because he’s like a big point guard. The offense is designed in such a way that it’s possible to start the play on either side of the floor using different entries, either with a pass or dribble.

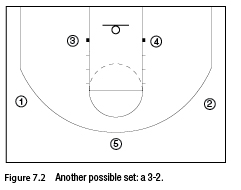

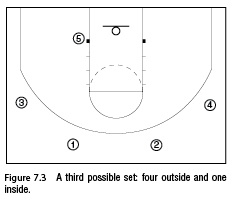

From this set the offense can evolve to three players out and two inside at the low-post (figure 7.2) or to four players on the perimeter and one at the low post (figure 7.3). None of these sets is permanent but is constantly changing.

Pass

Pass to the Wing. This is the easiest way to start the offense, but not the most common because many times the wings are overplayed. 1 is the ball handler in this example, but it could also be the off guard, 2. 1 passes to 3, the wing on his side. 1 can then cut to the same side as the ball or to the other side of the court.

Pass to High Post and Guards Cut or Exchange. If 1 can’t pass to 3, the wing, or reverse the ball to 2 because both are overplayed, he passes to 5, the high post, who has flashed to the free-throw area. 1 and 2 cut and go to the low-post positions on the same side as the cuts, while the two wings (3 and 4) replace the guards (figure 7.4). After the entry pass to the high post (5), 1 and 2 can exchange positions with the wings (3 and 4).

Dribble

Dribble Clear. If none of the other four teammates is free, 1 begins the play by dribbling toward one of the wings, a signal for the wing to clear out and cut backdoor to the basket, or else post down low (figure 7.5). 1 dribbles toward 3, who clears out and cuts to the basket.

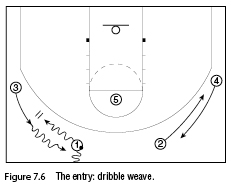

Dribble Weave. Another way to beat an aggressive defense that prevents the direct pass is to make a dribble weave. 1 dribbles toward 3 and then makes a short kickoff pass (or, if possible, a hand-off pass) to 3 if the defense plays loose; 2 and 4 can exchange positions (figure 7.6).

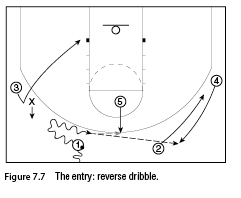

Reverse Dribble. The ball handler (1) can also dribble in one direction, make a reverse dribble, and then pass the ball to the wing (4), who has exchanged positions with 2 (figure 7.7). 1 can also pass to the post (5), who has popped out to the free-throw lane to get free.

Screen

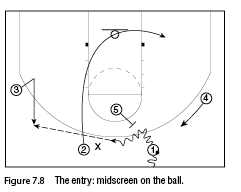

Midscreen on the Ball. 1 can also use a midscreen set by 5 as an entry on the offense (figure 7.8). 2, who is overplayed by his defender, cuts into the lane as soon as he sees 5’s screen on 1 and goes to the opposite corner; 4 and 3 come high, and 1 passes to 3.

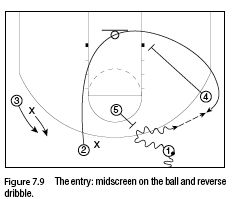

Midscreen on the Ball and Reverse Dribble. 1 receives a midscreen from 5 but can’t pass to 3 because he’s overplayed, so he makes a reverse dribble and passes to 2, who has come off the down screen of 4 (figure 7.9).

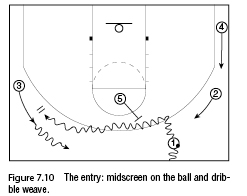

Midscreen on the Ball and Dribble Weave. 1 receives a midscreen from 5 and dribbles toward the wing (3), but 3 is overplayed, so 1 makes a dribble weave with him for a short kickoff pass or a hand-off pass, while 2 and 4 come up (figure 7.10).

Backdoor Cut

A trademark of the Princeton offense is the backdoor cut, one of the most basic and best ways of playing without the ball to beat an overaggressive defender. Players don’t need to fight the defender; rather, they run away from the pressure. The word “backdoor” describes exactly how this cut is done, but to use the move most effectively you need players who can make the pass to the cutter with proper timing and technique, usually via a one-hand bounce pass. All players on the offense must master the backdoor cut, whether they’re post or perimeter players.

We’ll now describe some situations for using the backdoor cut. The backdoor cut can be a pressure releaser, and it’s also used to get a player the ball on his way to the basket when his defender has lost sight of him or of the ball.

A key point to the backdoor cut is good timing between the cutter and the passer. The cutter must not make a banana cut; rather, he cuts at an angle and calls for the ball only when he’s sure to be open, giving the passer a target with his hand to indicate where he wants to get the ball. The passer must pass quickly, preferably with a one-hand bounce pass.

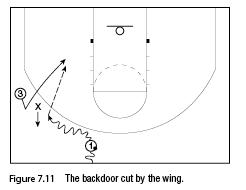

Wing

Direct Backdoor Cut. If the defender of the wing (3) tries to deny his receiving the ball, 3 makes a strong step toward the ball to create an overreaction from his defender, cuts hard behind him, and, if possible, receives the ball from 1 for a layup (figure 7.11).

Both Wings Backdoor Cut. With the ball in the hands of the post (5), both wings can fake going up and then make backdoor cuts if they are aggressively overplayed.

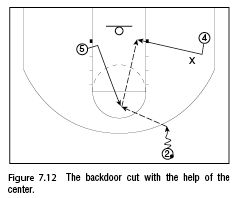

Backdoor Cut With the Help of the Center. This is another classic backdoor situation that requires perfect spacing and timing. The post (5) flashes to the high-post area and receives the ball from 2; 4 fakes going up and then cuts backdoor to receive the ball from 5 for a layup (figure 7.12).

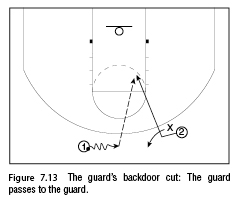

Guard

Backdoor Cut With the Pass From the Other Guard. If the guard (2) is overplayed and 1 can’t pass him the ball, 2 makes a direct backdoor cut (figure 7.13).

Backdoor Cut With the Pass From the Wing. If the wing (4) wants to pass to 1, but 1 is overplayed, 1 fakes going toward him and then cuts backdoor (figure 7.14).

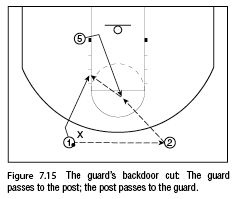

Backdoor Cut With the Pass From the Center. The guard (1) can also make a backdoor cut, playing with the post, 5, who flashes to the high-post area, receives from 2, and passes to 1 on the backdoor (figure 7.15).

Post

High-Post Backdoor Cut. If the defender of the high post (5) denies the pass reversal when the ball is in the hands of the wing (1), 5 fakes to go toward the ball and then cuts behind the defender to receive the ball from 1 for a layup (figure 7.16).

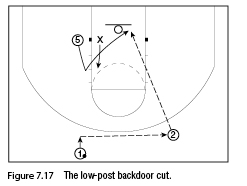

Low-Post Backdoor Cut. The backdoor cut can also be made from the low post. If 5’s defender denies his receiving the ball while he’s flashing to the high-post area, 5 makes a strong backdoor cut to receive the ball and shoot under the basket (figure 7.17).

Basic Action

As we’ve said, the initial set is a 2-3 formation, with two guards (1 and 2), two forwards (3 and 4) near the free-throw line extended, and one post (5), who can start from the low-post position and then flash to the high-post area at the elbows or at the free-throw area.

This is the initial formation, but remember that all the players are interchangeable on the court and also that we can start the action on both sides of the court or by passing to the high post. As we mentioned, the four perimeter players must be able to play both the guard and wing position because they’ll often exchange their positions on the court. The “basic” has three set options:

• Pass and screen away from the ball.

• Pass and cut away.

• Pass and follow the ball (high split).

Pass and Screen Away From the Ball Set

We’ll now show different options for the screen away from the ball based on defenders’ reactions.

Option 1. 5 flashes to the high-post position and receives the ball from 1; 1 then screens away from the ball for 2, who cuts backdoor and moves to the other side of the court, where he receives a down screen from 3.

As you can see just from these two simple moves—one side screen and one down screen—we keep all the defenders busy and create several options for shooting. 5 can pass to 2 on the backdoor when he comes off the screen set by 3, or, if 2’s defender cheats on 3’s screen, when he runs back under the basket. 5 can also pass to 3, who rolls to the basket after the screen; or 3 can post down low and receive the ball from 1 (figure 7.18). Finally, 5 can also pass to 1, who pops out after setting the screen.

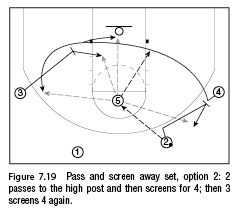

Option 2. 2 passes the ball to 5 and then screens for 4, who goes backdoor, while 2 pops out. 5 can pass to 4 for a layup when 4 comes out of 3’s screen, or, if 4’s defender cheats on 3’s screen, when he runs back (figure 7.19). 5 can also pass to 2, who pops out after the screen, or to 3, who rolls to the basket after setting the screen, or 3 can post down low and receive the ball from 4.

Option 3. Let’s now assume that 1 can’t make the entry pass to 3 or to 5, and he can’t reverse the ball to 2 to start the offense on the other side of the court. 1 then drives toward 3 for a hand-off pass, while 2 and 4 exchange their spots (figure 7.20). 3 passes to 4 and 4 passes to 5, who has flashed to the elbow, while 3 cuts to the other side of the court. 5 can pass to 3 (figure 7.21).

4, after passing to 5, screens for 2, who goes backdoor, cuts to the other side of the floor, and is screened for by 1, who then goes to the corner. 5 can pass to 2 on the backdoor, or to 4, who, after setting the screen for 2, rolls to the low-post position or pops out. 2, if he doesn’t receive the ball from 5, continues his cut and rubs off the screen set by 1. If 2’s defender cheats on 1’s screen, 2 runs back and receives the ball from 5 under the basket (figure 7.22).

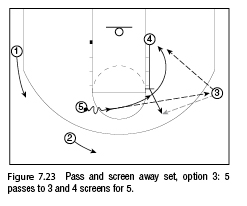

If there’s no solution, 5 makes one or two dribbles to the other side of the court and passes to 3. 4 then back-screens for 5, who receives the ball from 3. 3 can also pass to 4, who has popped out after the screen (figure 7.23).

Option 4. 2 reverses the ball to 1, and 1 passes to 3, while 2 cuts to the other side of the court. 1 screens down for 2, while 5 pops out of the lane (figure 7.24).

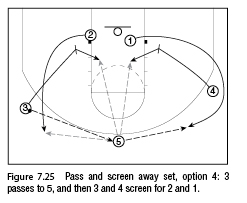

3 passes to 5 and screens down for 2, while 4 screens down for 1. 5 can pass to 2 or 1, who come out of the down screens of 3 and 4, respectively, or to 3 or 4, who have rolled to the basket after the screens. If nothing happens, 5 passes to one of the two guards—to 1, in this example (figure 7.25).

After the pass to 2, 5 then screens away for 1, who goes backdoor, while 2 dribbles to the other side of the court. 2 can pass to 1 on the backdoor, or to 5, who rolls to the basket after the screen (figure 7.26). After the pass to one of the guards, who came up after the screen, 5 can also post down low.

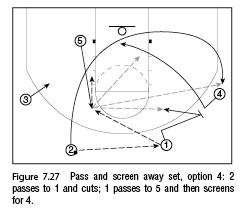

If, after the pass to 2, 5 posts down low, he can then flash to the high-post area at the elbow, while 2 passes to 1 and cuts to the other side of the court. 5 receives the ball from 1, then 1 screens away from the ball for 4, who goes backdoor, while 1 pops out. 5 can pass to 2 on the cut or when 2 comes out on the other side of the floor, or 5 can pass to 4 on the backdoor or to 1, who has popped out after the screen (figure 7.27).

Option 5. 1 passes to 2, cuts and screens for 5, and then goes out on the wing on the other side of the court. 5 goes to the high-post position and receives from 2, who then screens for 4, who goes backdoor. 5 can pass to 4 on the backdoor, to 1, who pops out after the screen, or to 2, who rolls to the ball after screening for 4 (figure 7.28).

Pass and Cut Away Set

We always want to have the four perimeter spots occupied, and we also want to constantly move the defense so we don’t have a weak and strong side of the court. For this reason, we tell our players that they can also pass the ball and cut away from the ball. Here is an example; from the previous plays, you can see that the pass and cut away is an important move of this offense.

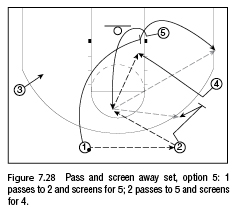

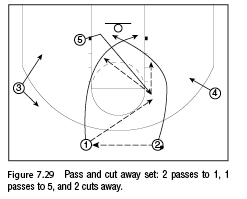

2 passes to 1; 5 flashes to the high-post position at the elbow opposite the ball; 1 passes to 5; 2 cuts to the other side of the floor; 1 cuts and goes to the opposite side of the court, timing his cut after the cut of 2 (figure 7.29). 5 can pass to 2 or to 1 on the cut.

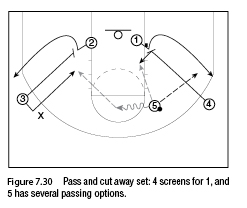

While he’s coming out of the lane, 1 receives a down screen from 4 (or he can replace 2). 5 can pass to 1 off the down screen of 4, or to 4, who rolls to the basket after the screen for 1. If 5 can’t pass to 1 or 4, he dribbles toward 3, who, if he’s overplayed, goes backdoor and can receive a pass from 5 (figure 7.30). 3 can also screen down for 2, and 5 can pass to 2. In this case, if 2 can’t shoot, he can pass to 3, who has posted down low.

Pass and Follow the Ball (High Split)

As we’ve said, in this offense the post must be a good passer and able to read different defensive situations. 2 passes to 1 and cuts to the opposite side of the court, while 5 flashes to the high-post position at the elbow opposite the ball to receive the ball from 1. 5 can pass the ball to 2 on the cut or after 2 comes off 3’s screen (figure 7.31).

If this solution is not possible, these are the alternatives:

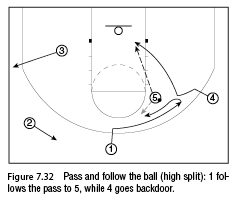

• After the pass to 5, 1 follows the pass, while 4 fakes a split and goes backdoor to receive from 5 (figure 7.32). 5 can also pass to 1, who pops out.

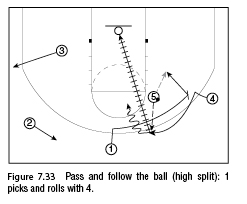

• 1 screens for 4, and 4 receives the ball for a jump shot or a drive to the basket (figure 7.33). 5 can also pass to 1, who rolls to the basket.

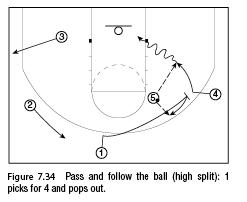

• 1 screens for 4, 4 goes backdoor, and 1 pops out for a jump shot (figure 7.34).

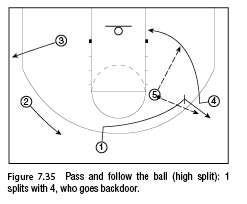

• 1 splits with 4, who goes backdoor and then to the low post; 1 then pops out to the wing area (figure 7.35).

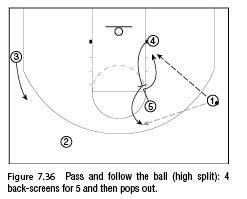

• After the pass to 1, 5 is back-screened by 4 and receives the ball from 1 (figure 7.36). 1 can also pass to 4, who pops out after the back screen.

Options to “Basic”

No matter what type of offense you run, you must have different options to start your play in case the defense stops your primary entry option. As we’ve said, there are two basic options for starting a play: either with a pass, as we described previously, or with a dribble. In this section we’ll review options for starting the offense with a reverse dribble.

Reverse Dribble

Option 1. 1 can’t pass to one of his teammates, so he starts to dribble toward 2, who cuts away from the ball to the opposite side of the court; 1 then reverse dribbles toward 4, who goes backdoor (or screens for 2) and then to the low-post position; 5 flashes to the elbow on the weak side (figure 7.37).

After the reverse dribble, 1 passes to 2, receives a side screen from 5, and gets the ball from 2 for a jump shot or a drive to the basket. 2 can also pass to 5, who has rolled to the basket after the screen. 2, after the pass to 1, can also screen down for 4, and 4 can receive the ball from 1 (figure 7.38).

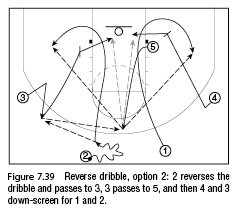

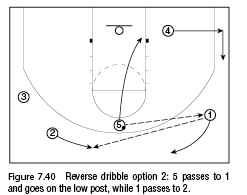

Option 2. 2 dribbles toward 1, then reverse dribbles and passes to 3; 5 has flashed outside the lane to receive the ball from 3. 2 and 1 cut to the same side of the court from which they started and are screened respectively by 3 and 4 (figure 7.39). 5 can pass to 2 or 3 off the screens or to 4 or 5, who have rolled to the basket after the screens. 5 passes to 1 and goes to the low-post area, while 4 goes outside the three-point arc. 1 passes to 2 (figure 7.40).

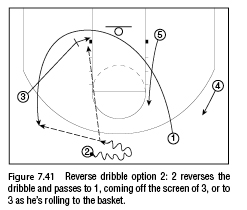

2 then starts to dribble toward 1, who cuts in the lane and comes out on the other side of the court, brushing off the screen of 3. 2 makes a reverse dribble and passes to 1 or to 3, who rolled to the basket after the screen (figure 7.41). 1 passes to 3, while 5 side-screens for 2 and then pops out (figure 7.42). 3 can pass to 1, who spots up, to 2, to 5, or to 4, who spots up.

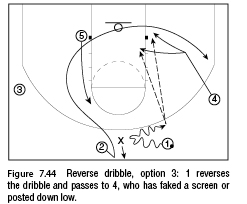

Option 3. 2 is overplayed, so 1 dribbles toward him; 2 makes a backdoor cut and gets out on the opposite side of the court. 1 reverse dribbles and has these options on the strong side:

• 4 screens for 2 and then rolls to the basket (figure 7.43).

• 4 fakes the screen and cuts to the basket.

• 4 posts up down low (figure 7.44).

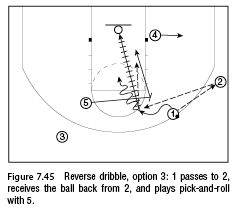

1 can also pass to 2, receive a screen from 5, and get the ball back from 2; 1 then plays pick-and-roll with 5 (figure 7.45).

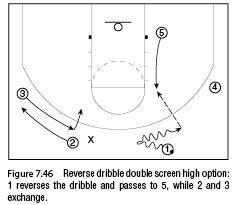

Reverse Dribble with Double Screen High

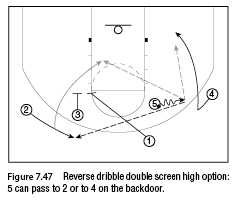

1 dribbles toward 2, who is overplayed and can’t receive the ball, so 2 and 3 exchange spots as 1 reverses the dribble and passes to 5, who has flashed to the elbow (figure 7.46). 3 and 1 double-screen on the other side of the court. 5 has these options:

• Pass to 2, who rubs off the double screen high or low.

• After a couple of dribbles, pass to 4, who cuts backdoor if he’s overplayed (figure 7.47).

• Pass to 2, who fakes to rub off the double screen and then cuts backdoor.

• Pass to 1, who pops out of the screen (figure 7.48).

Chin

This action, called chin, starts with a back pick by the high post on the weak side of the half-court.

Option 1. 2 passes to 1, then rubs off the back screen set by 5 and gets to the other side of the court, while 1 passes to 3 (figure 7.49). 3 can pass to 2. If 2 can’t receive the ball, 5 screens on the other elbow for 1, who receives the ball from 3 for a shot or a drive to the basket (figure 7.50). 5 can roll to the basket in the opposite direction of 1 and receive from 3.

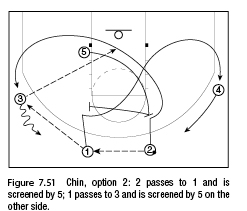

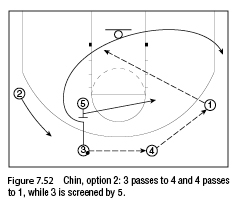

Option 2. 2 passes to 1, rubs off the back screen of the high post (5), and cuts to the other side of the court. 1 passes to 3 and 3 dribbles to the right, while 5 screens for 1, who cuts to the opposite side of the court and replaces 4, who gets to the guard position (figure 7.51). 3 passes to 4 and 4 passes to 1, while 3 rubs off the back screen set by 5 and goes to the ball-side corner. 1 can pass to 3 (figure 7.52).

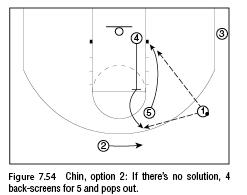

If nothing happens, 5 flashes to the other elbow and back-screens for 4 (figure 7.53). 1 can pass to 4. If 4 can’t receive the ball, he comes back and back-screens for 5. 1 can pass to 5 or to 4, who pops out from the screen (figure 7.54).

Chin Pass to Strong Side (Flare Action)

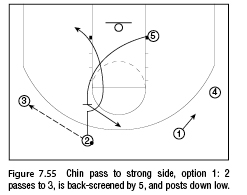

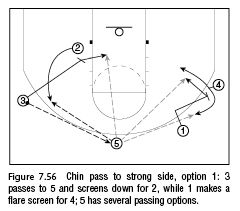

Option 1. 2 passes to 3 and receives a back screen from 5, who has flashed to the strong-side elbow. 2 posts down low on the ball side, while 5 pops out after the screen (figure 7.55).

3 passes to 5 and then screens down for 2, while 1 makes a flare screen for 4. 5 has several options (figure 7.56):

• Pass to 2, who comes off 3’s screen.

• Pass to 4, who comes off 1’s screen.

• Pass to 3, who rolls to the basket after setting the screen for 2.

• Pass to 1, who rolls to the basket after setting the screen for 4.

4 can also make a backdoor cut if his defender slides over the screen.

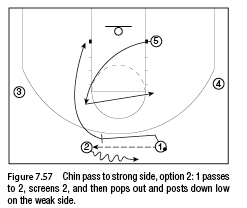

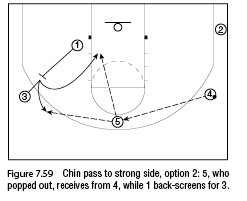

Option 2. 1 passes to 2, screens on the ball, and pops out to replace 2. 2 dribbles on the other side of the court, while 1 posts down low on the weak side and 5 gets to the other elbow (figure 7.57). 2 passes to 4, rubs off the back screen of 5, and goes out on the ball side, while 5 pops out after the screen (figure 7.58). 5 receives the ball from 4, and 1 screens for 3, who pops out and receives from 5 (figure 7.59).

Sets Out of the High Pick

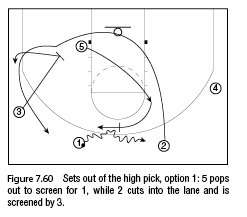

One of the possible entries on this offense is the high pick. From this entry we can start different sets.

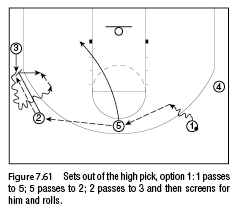

Option 1. 5 flashes to the elbow, then pops out and sets a high screen for 1. 2 cuts into the lane, is screened for by 3, and gets out to the other side of the court, replacing 1 (figure 7.60). After the screen, 5 rolls outside.

1 reverses the dribble and passes to 5; 5 passes to 2 and then posts down low; 3 gets outside the three-point arc. 2 passes to 3 and screens on the ball. 3 drives to the basket or passes to 2, who has rolled to the basket (figure 7.61).

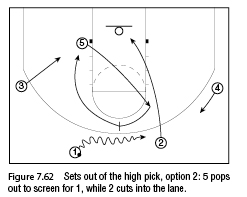

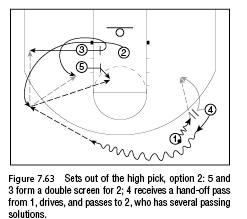

Option 2. 5 flashes to the elbow, pops out, and sets a high screen for 1, while 2 cuts down low (figure 7.62).

After the screen, 5 runs down and forms a double screen with 3 for 2, who rubs off and gets out to the three-point arc. 1 dribbles toward 4 for a hand-off pass to him. 4 dribbles to the other side of the court and passes to 2. If 4 is overplayed, he can go backdoor while 1 is dribbling toward him. 2 can also pass to 5, who rolls to the basket, or to 3, who can pop out or curl around 5 (figure 7.63).

Implementing the Offense

Some coaches are reluctant to adopt this offense. It’s wise to be cautious before accepting and implementing any particular manner of attack. However, any drawbacks to this offense are more imagined than real. We’re convinced this style of offensive play has far fewer shortcomings and many more appealing features than the popular alternatives, so let’s address what we’ve heard coaches cite as their major concerns.

• The offense is too slow to develop. True, this offense requires a bit of patience. It might very well take a while before the offense gets an open, high-percentage shot during a possession. And that’s the point: It forces the defense to work over longer stretches, reacting to the players’ and the ball’s movement. But just because the offense might require more passes and more seconds might tick off the shot clock before a field-goal attempt is made doesn’t mean the offense is slow. Indeed, it’s far faster than an offense in which players dribble too much, cuts are made too slowly or not at all, and passes are deliberate and telegraphed. In our offense, the ball never remains in one player’s hands for more than a couple of seconds, and the players without the ball are constantly moving (cutting or screening). Plus, we don’t have to waste time calling out plays or resetting the offense; players can flow immediately to new solutions without losing time. And, typically, there’s more than one good opportunity to score per possession—but if the first backdoor cut is open for a layup, hey, we’ll take it.

• The offense is difficult to teach. Because execution is the key to any set, as with any offense, you need to take care and practice details when learning it and all its options. Think of it this way: You’re not teaching an offense but are teaching the game of basketball, including all the basics a player must master to play the game well. If a player can master the fundamentals involved in this offense, he can play in any other type of offense. By adopting and working on this offense, a coach improves not only his players’ offensive skills but also their defensive skills, because they must work on any type of defensive situation that occurs on the court, including screens on and off the ball, every type of cut, blocking out in difficult situations, and so on.

• This offense hampers players’ scoring averages, and the best scorer on the team gets fewer touches. Would you prefer to have a happy scoring leader who’s averaging 30 points a game on a losing team riddled with dissension caused by selfishness and a one-pony style of attack, or would you prefer having every player participate in and contribute to the offense of a successful and cohesive team, though no individual averages more than 18 points? And, considered from a different angle, which team would you rather defend—the team with only one threat or the team with five threats? Basketball is a team sport, and the team wins, not a single player. Besides, gifted offensive players can and do shine in the Princeton offense, though their scoring stats might not be as gaudy as another team’s gunners.

• This offense gives more freedom to the players, so the coach has less control. This is true. But, then again, a coach’s sense of control in other offenses is no more than an illusion. Ultimately, the fundamentals and execution of players determine the success of any team. We as coaches can’t shoot, pass, dribble, or make the hundreds of on-court decisions for players during the course of a game. The last thing any coach should want are robots on the court. Instead, we find great satisfaction in seeing our players take the principles they’ve been taught and practiced and apply them most effectively during competition. And we know our players appreciate the respect we show for their unselfishness and decision-making skills by allowing them such freedom.

Final Points

A few final points on teaching and practicing this offense: Emphasize working on those things that matter—the skills needed and situations most likely to be encountered in a game. Don’t waste hours of practice time on drills that don’t mean much when it comes to how your players and team perform in competition. If you watch what your players are doing when they play, they will show you what to teach them.

When you do work on a drill that’s directly related to game performance, put maximum effort and concentration into it. The quality of work is more important than quantity, though the best drills should be repeated often and done right. With this offense, as with others, taking shortcuts only adds to shortcomings. Winning is in the details, and we hope you have learned enough about the Princeton offense to at least seriously consider it as an option for your team.