Chapter 9

Fast-Break Principles

George Karl and Doug Moe

All coaches have their own personalities that are reflected in the style of play of their teams. In our case, we’re pretty assertive guys and not very patient. So we prefer to play up-tempo and create offense through defensive pressure. And, when we get the ball, we want to force the action.

Nothing against coaches who choose to have their teams walk the ball up the court, run set plays, and execute a more methodical offensive attack. That’s just not us. We favor the fast-break offense for several reasons:

• It’s harder to prepare for and defend because it has no strictly defined positions or set plays.

• It hurries many opponents, setting a tempo faster than they prefer to play.

• It wears down the opposition, who will typically like to run less than your players and won’t be as well conditioned to run more.

• Run properly, it produces more easy and open shots than an attack that allows the defense to get in place.

• It’s generally more fun for players because they get more shot attempts, use a greater variety of skills, and get to be involved more, both through more passing and more frequent substitutions.

History shows that every championship team has good chemistry, good spirit, tough defense, a positive, unselfish offensive energy, and a play-hard intensity that doesn’t waver. So, in addition to our personal preference, we have a solid rationale for employing a high-speed attack. Let’s look at each of those five reasons in greater detail.

Be hard to guard. Because only the point guard in our system has what could be called a defined role, the opponent is challenged to match up with us every time we break down the court. And because the whole offense is based on players responding to each situation, the defense has no real notion of how the attack will materialize on any given possession. This lack of predictability is very unnerving to opposing coaches and players, and a big plus for the fast-breaking team.

Rush the opposition. The very pace of a high-speed, fast-break offense often unsettles opponents. Their comfort zone is disrupted because they have to think and move faster than they do against other teams. Rather than dictating a more leisurely tempo, they are now reacting to—and trying to keep up with—what seems to them a helter-skelter style of play. When this happens to the opposition, you’ve got them where you want them. Not only will their defense suffer many breakdowns, but their transition game and offense will move into a quicker mode than normal as well, which leads to turnovers and poor shot selection on their end of the court.

Fatigue the opponent. You can’t count on the opposition being out of shape; any coach worth his salt will have his players fit enough to compete and win. But being in condition to run a standard, set offense and being physically prepared to play a high-speed, fast-break attack for a full game are two different levels of conditioning. And a winded or tired player is a very vulnerable player. So what you’ll see during long stretches of continuous play and in the second half of games is the opposing team suffering defensive breakdowns, coming up short on its shots, and having to go deeper than it would prefer on its bench. Just watch how opponents of the better fast-breaking teams start tugging on their shorts during every dead ball. The pace takes its toll on athletes who aren’t trained to handle it.

Produce more and easier looks. At its most fundamental level, winning comes down to scoring more points than the opponent. We believe the best way to do that is to create more possessions and scoring chances than the opposition. A successful fast-break attack generates more shots. In addition, because the defense won’t have time to get in position every time down the court, it is more likely that one offensive player will get free for a jumper or a layup, which should increase your shooting percentage.

Use players’ preferred style. Although not a determining factor in our deciding to commit to the break, another plus is that players are enthusiastic about playing a fast-paced style. Whether a freshman in high school or a second-year pro, most athletes are going to want to display their talents in an open-court situation rather than be confined in a more restrictive half-court attack. But taking part in a fast-break offense isn’t easy. Those who contribute to a fast-break system must sacrifice as well, as we’ll see when it comes to putting such an attack in place.

Implementing the Fast Break

Becoming a running team doesn’t happen with a snap of the fingers. It’s a process that involves firm and clear instruction and correction by the coach, and gradual acceptance by players until the system becomes second nature to them.

What’s essential is that everyone involved in the program understands that the team and coaching staff are committed to playing that style all the time. The fast break starts with establishing an unquestioning mind-set that eliminates hesitation and doubts, and instead thrives on a full-speed-ahead attitude and instincts developed through countless repetitions.

Apply Defensive Pressure

Every championship team has high energy on defense. That go-hard intensity you’re looking for from players on the offensive attack must also be evident when the opponent has possession.

Good fast-breaking clubs bring their defense to the offense; they don’t wait and react to what the offense does. This makes sense when you consider the unfamiliar, up-tempo pace at which you want the opposing team to play.

Perimeter pressure is especially important to prevent, or at least discourage, their guards from playing catch outside, running the clock, and slowing the game down until they decide to shoot or dump it inside to the post. We’ve benefited from coaching some outstanding defenders over the years. T.R. Dunn was a tremendous perimeter defender with the Nuggets’ teams of the 1980s. Of course, Gary Payton earned his reputation as one of the NBA’s all-time best defensive guards (hence his nickname, “The Glove”) playing in Seattle on some of the Sonics’ fine teams.

Yes, we want defenders to go for steals when the percentages are with them. Such takeaways should lead to easy buckets on the other end. But we don’t want our players taking chances, foolishly reaching, fouling, or getting out of position to allow an easy score. The key is for defenders to play hard and smart, and to assess the risk–reward of each possible steal attempt. Good, sound defensive pressure should disrupt an offense enough to generate a high number of turnovers without taking too many chances.

Rebound the Ball

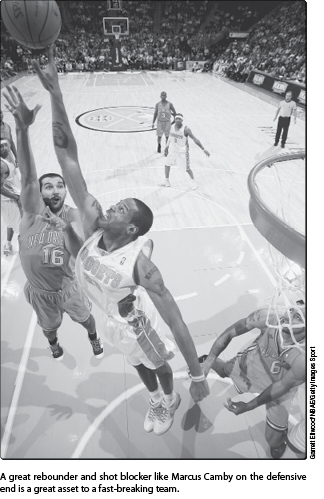

Obviously, besides turnovers and steals, the only other way to gain possession (other than after an opponent has scored) to start the break is to rebound missed shots by the opposition. So there’s no way to overemphasize the importance of rebounding in a running system.

Where so many teams that want to run fail is in too few of their players attacking the defensive boards. Instead, they have three or four guys cherry-picking, out at half-court looking for an outlet pass from the only guy on the squad who’s going after the ball. To prevent that from happening, we demand that four players (all except the point guard) attack the glass every time the opponent shoots. They are not allowed to start toward the offensive end until they or a teammate claim the rebound.

Sprint the Court

Once possession is gained, the scene on the court should look like runners exploding out of their starting blocks to run a race. Our guys must think full-speed ahead and take off without hesitation.

Only with this mental approach can players fully accept the physical challenge of playing our energy-sapping style. The best up-tempo teams don’t just run, they sprint—the whole game. Breaking through that mental barrier of the natural inclination to rest or run less than full speed is perhaps the biggest hurdle to becoming a full-court fast-break club. This approach is something a coach must insist on every day in practice and in games, and correct immediately if the pace of the team up and down the court starts to slow.

Move the Ball

The effort required to sprint the court is worthwhile only when combined with equally fast movement of the basketball. Nothing puts the brakes on the break quicker than a player holding the ball in a stationary position. Quick passes, on the other hand, are impossible for even the quickest defenses to stop. It’s quite simple—if you move the ball faster than the defense can react, someone will have an open shot.

Of course, it helps if those quick passes are accurate. Hitting a teammate in stride where the ball can be caught easily and converted quickly into a shot attempt is the goal. Sloppy passes that require a receiver to make an adjustment just to gain possession allow the defense to catch up to the ball and perhaps create a turnover or deny what would have been a good shot attempt that trip down the court.

Moving the ball also has the beneficial effect of wearing down an opponent. Making the defense work continuously through each possession just to keep up with the ball and to try to deny passing lanes will take its toll over the course of a game.

Take Quick, Good Shots

The final piece of the puzzle is to insist that players shoot the ball quickly. If players pass the ball around the perimeter and run the clock down while looking for a perfect, wide-open shot each time down the court, you’re in trouble. They need to have the green light and take immediate advantage of shot opportunities on the primary and secondary breaks. If the shot clock comes into play when you have the ball (and you aren’t simply expending time at the end of the first half of the game), this should send a warning signal. We don’t recommend anything like a “chuck and duck” shooting mentality, but the whole basis for this system is a relentlessly fast attack.

To do this, players must develop a good sense of what is and isn’t a “good” shot for them, and be very confident in what they define as good. Their sense of good versus bad shots comes largely from the coaches’ feedback during practices. Once their good shots have been defined, players must be prepared—even eager—to take those shots during games.

We do not set strict rules, but our players must understand their roles and be conscious of their offensive ability and the range of their shot. For example, Carmelo Anthony has great offensive skills and is free to shoot on a fast break whenever he wants. Other players, such as Marcus Camby and Kenyon Martin, are not our best options for the first shot on the fast break or when they’re open on the perimeter, because they possess different offensive skills.

Executing the Fast Break

When it comes to running our break, the rules are few. The freedom we allow execution-wise has a purpose—we want players to learn to think for themselves and react instinctively in the most effective manner in each situation. That’s because each situation on any given break presents unique challenges and opportunities. If we were to preprogram players to always move to a certain spot on the court or always run the same pattern, we’d make life much easier for our opponent and miss a lot of scoring chances along the way.

This less-structured approach is a good basis for player development. Through being forced to make many fast decisions on the fly repeatedly every practice, they gain a good sense of what the game is about and how to play it. Mind you, it won’t always be pretty, but it’s essential that you stand firm behind what you’re teaching and stay positive with the players.

When we were implementing the offense in Denver, we had an exhibition game in Wyoming versus Golden State. The Warriors just killed us, and we committed 30 or more turnovers. After the game, everyone was commenting on how poorly we were executing the break and even suggesting that we might want to slow down our offensive attack. So they were surprised when we sounded so optimistic after the blowout. From our perspective, our pressure defense was great, our rebounding was great, and our running was great. What we hadn’t quite developed yet was a feel for the passing game.

Starting Point

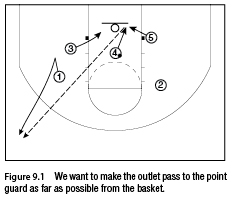

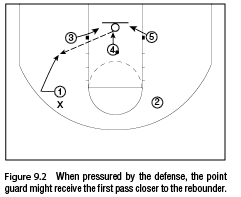

As we mentioned before, only one position on our team has a defined role in our break. The point guard is responsible for receiving the ball from the rebounder (assuming the point guard hasn’t rebounded the ball). We’ll emphasize once again just how important defensive rebounds are to making a fast break successful. When the opposition shoots, your players must crash the boards with all their might and make sure they get the ball quickly to the point guard, who should either come to the ball or create a clear passing lane between himself and the rebounder. We want our point guard to receive the outlet pass as far away as possible from the defensive basket (figure 9.1). He’s our main target when we start the fast break. However, if there is good defensive pressure on him, making this first pass extremely difficult, we want the guard to quickly come in closer and get the ball (figure 9.2).

Once the ball is in hand, the point guard quickly brings the ball up the middle of the court, where defenders can’t use the sideline to trap him. We believe having the ball in our point guard’s hands places pressure on the defense. The point guard can penetrate to the basket, pass the ball to an open teammate, shoot a pull-up jumper, or even launch a three-pointer on occasion. In our system, as in many fast-break attacks, the point guard is the key cog in initiating the offense and making the first key decision in the frontcourt.

Winging It

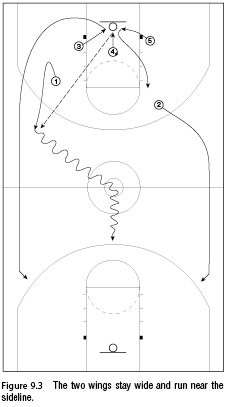

Once possession is gained, the two players closest to the wings (roughly the free-throw line extended on each side of the court) should sprint to those spots. We want them as wide as possible to create space to allow more room for the point guard to receive the ball from the rebounder. Then, as the point guard takes off with the ball, the wings dash down opposite sides of the court, staying wide until they reach the free-throw line extended on the offensive end (figure 9.3). The most difficult thing to teach the players who run on the wings is to stay wide. The wider they are, the better the passing lanes, thereby increasing our chances to score.

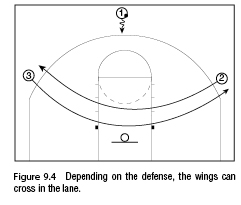

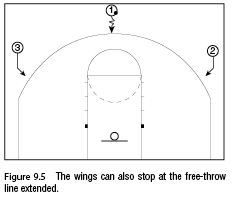

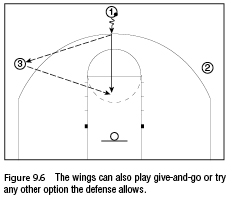

Again, we don’t force any rules on the wings. Depending on the defensive situation, they must read and react. In short, the two wings can cross in the lane (figure 9.4), they can stop at the free-throw line extended (figure 9.5), they can play give-and-go with the point guard (figure 9.6), or they can try any other option the defense allows.

Ideally, your 2 and 3 players will fill the role of the wings most of the time. They’ll usually be faster than your big men and better able to convert a scoring opportunity during the initial onslaught. But we don’t have any strict rules on this because in some cases the 4 or 5 could fill the wing lane.

Support Troops

Assuming your 4 and 5 players gain the majority of your defensive rebounds, they’ll most often be the last two team members up the court. If 4 grabs the rebound, he’ll fill the lane between the point guard and a wing on one side of the court. 5 will trail the point, moving to a position near the top of the key (figure 9.7).

As with the wings, the spacing of the two trailers is important. They should be far enough apart that they both can’t be covered by one defender, and they must stay aware of what’s happening as they run upcourt, ready to alter their paths as necessary.

Primary Break

As you’d expect, quickness and speed are vital to the primary break. By “primary break” we mean a fast break run when there’s a real advantage over the defenders.

In all situations in which there’s an offensive advantage, defenders are outmanned and kept off balance, creating a variety of possible mismatches. The defense simply can’t cover all spots on the court. Instilling this notion in our players is not as simple as it seems, and coaches must teach and practice these situations regularly, using a few basic and practical rules to increase the odds that the advantage will go to the offense.

However, before discussing the fast-break rules and how to teach them, we want to say something about the mental game. We’re convinced the first ingredient of an effective fast break is the mental switch, the “offensive transition”—that is, rapidly changing the mind-set from defense to offense within a split second. This quick switch must occur after a basket, a defensive rebound, a steal, a turnover, a sideline or baseline inbounds play, or a made shot or free throw.

Following a score by the opponent, if the inbounder is slow to inbound the ball, or, following a defensive rebound, if the rebounder doesn’t make a quick outlet pass, the fast break will almost certainly be affected. We think an extremely quick “mind switch” is the basis of an effective fast break.

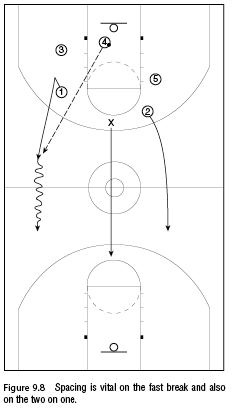

The second fundamental aspect of the fast break is running. The main rule here is that players must always maintain proper spacing on the court. If the offense runs a two-on-one fast break and the two offensive players are too close to each other, one defensive player might effectively guard the two players and prevent what should have been an easy basket (figure 9.8).

These are the premises from which a coach can build the primary break, and without these two vital aspects, we don’t think a primary break can be successful. Basketball is a game of habits, and these two habits must be taught and practiced to be reinforced. It’s a big mistake to skip the teaching and learning of these basics. Failing to do so is like driving a Ferrari equipped with motorbike tires: You won’t get anywhere!

Coaches personalize their fast-break approaches, as can be seen from coach to coach. Some coaches run their primary break on the sideline or in the middle of the court (figure 9.9); others want the two wings to cut at the free-throw line extension or else work off a give-and-go move.

We’re different from the majority of coaches because we don’t give our players specific rules. We tell them to react to what the defense gives them. This doesn’t mean our philosophy is necessarily better than that of others—just that it works best for us. As always, you’ll want to gear your approach around your players.

Secondary Break

The secondary break occurs after the primary break has failed to produce a basket. In this case, the team quickly tries to take advantage of the defense—which is still not yet set—and find a quick-scoring play. On the secondary break, all five offensive players are involved. Normally, the secondary break lasts just a few seconds and tries to punish the ill-formed defense (characterized by poor matchups and bad rotation).

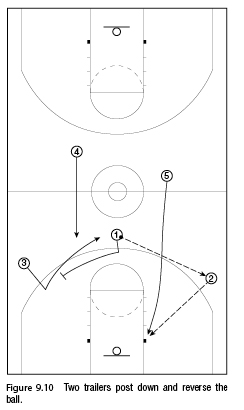

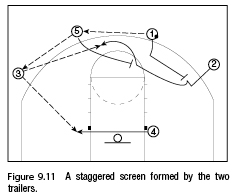

There are many ways to run the secondary break, but the break typically involves one or two trailers, generally the big men, who are used for reversing the ball and posting down on the low-post position (figure 9.10) or for a stagger screen for an outside shot (figure 9.11).

We don’t have an established secondary break. If we don’t score right away, we immediately run our passing game, which in effect is our secondary break, including cuts, backdoor plays, the give-and-go, and screens on and off the ball.

Again, we want to underline that the game and the decisions belong to the players, who react to the defense, and that they don’t depend too much on the input of the coaching staff. The players must be responsible for their moves and decisions: We don’t want to call every play like a teacher in a classroom directing her students.

One of our favorite and most respected coaches, Dean Smith, was convinced that to have a good passing game without rules you needed five very smart players on the court—which is not always possible. He believed that if you lacked savvy players, you needed to set rules, lest your passing game be ineffective. With all due respect to Coach Smith (and there is much that is due), we happen to think differently. We believe players must have the freedom to make the proper decisions on the court based on the reaction of the defense. However, based on the number of ACC and national championships Coach Smith won and the dozens of All-American players he coached, maybe, just maybe, Coach Smith was on to something.

Drills for the Fast Break

Our practices typically last no longer than 75 to 90 minutes. We believe you get more out of high-speed, high-concentration practices than you do long sessions, when physical and mental fatigue set in.

Our typical practice focuses on the fast break and teamwork. More isolated drills have their place with developing players, especially in the off-season and preseason, but once the competitive season gets under way, our emphasis shifts to helping our squad execute as a unit.

Standard Practice Session

Three-line full-court fast break 10 to 15 minutes

Five-player passing game fast break 15 minutes

Half-court defense with a fast break 30 to 40 minutes

Scrimmage 20 minutes

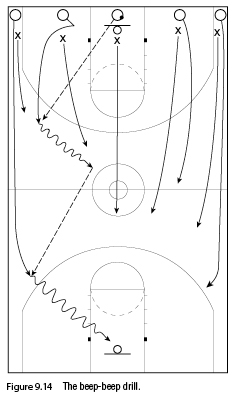

The three group drills we run to develop and sharpen our execution on the break are the three-line and five-player breaks and what we call a “beep-beep” drill. Here’s how they work.

Three-Line Drill

We run this drill as a way to teach our wings to stay as close as possible to the sidelines. They must start to run only when the point guard receives the ball and starts the dribble. We form three lines, toss the ball off the backboard, and start the fast break without the defense (figure 9.12). Players are free to cut at the free-throw line extension, make a give-and-go, or try any other variation as long as they maintain proper spacing.

Five-Player Passing Game

The second drill is a five-player passing game drill without the defense (figure 9.13). We run this drill until one player asks for a time-out because he’s out of gas. Players can run any options they want on the passing game, but everything must go at full speed.

Beep-Beep

We call this five-on-five drill “beep-beep” after the cartoon character the Roadrunner. We tell our players the rule is that the point guard must bring the ball down as quickly as possible on offense and either shoot as quickly as he can or make only one pass, and that whoever receives the pass must shoot immediately (figure 9.14). The defense then switches to offense and runs the play down the other end of the court. This drill works the fast break and conditioning at the same time.

We run all our drills at top speed to help our players maintain the essential habit of sprinting the court. The pace also raises the level of competition during practice, which in turn challenges players to step up their performance each time on the court, not just in games.

Finishing Up the Fast Break

Many coaches are reluctant to adopt the fast break as a primary offensive attack, citing the various challenges to playing an up-tempo style. To close the chapter, we’ll address the common concerns coaches have about committing to a running system. Just remember that no system is flawless, and whatever means of attack you choose will require fine-tuning to your situation and personnel.

• What happens when the team lacks a capable point guard? Admittedly, this is probably the Achilles’ heel of the fast-break system. It’s very difficult to have much success without a playmaker who can put pressure on the defense each time down the floor. At the high school level, what you must do is ensure your feeder schools are developing players who can step into this role when they come of age. At the college level, you must make your point guard position a priority for at least every other recruiting class. And at the pro level, you need to draft or trade for at least a starter and capable backup point guard if you hope to have success running the fast break.

• Can the break be effective without an especially fast team? That’s like asking if you can rebound without a tall team. The answer to both is yes, but it sure helps when players have the physical tools so they don’t always need to work that much harder than the opposition just to keep on a level playing field. If your team is overmatched from a speed standpoint, you can still run the break effectively with superior conditioning, hustle, smarts, techniques, and tactics. The important thing is that the players don’t consider their lack of speed a handicap or use it as an excuse when they come up short. Sharp cuts, quick passes, and fast thinking can offset faster feet.

• Don’t fast-breaking teams commit too many turnovers to win consistently? If you adopt a fast-break system, you must accept that you’ll incur more turnovers. That’s not because your team is being loose with the ball or playing too risky—it’s just that there are so many more possessions, trips down the court at a high speed, and passes to be thrown and received. That all adds up to a higher turnover total for a fast-break team than for a half-court club. We don’t like a high number of turnovers, but we believe a more important statistic is turnover ratio. As long as we consistently have fewer turnovers than our opponents, our per-game turnover average isn’t that much of a concern.

• Won’t the team wear down over the course of a season? Yes, the cumulative effect of a running game can take its toll in a season as long as the NBA’s. That’s why we keep our practices short and more intense. It also helps to have a decent bench, so you can call on your 8, 9, and 10 players to give your starters occasional rests. At the college and high school levels, you can maintain a higher pace over the season because the season and length of games are shorter. Plus, players are younger and less susceptible to the kind of fatigue that athletes encounter in their pro careers. We always felt that the conditioning factor—both in a particular game and over the course of a season—was in our favor because we were well trained to maintain the fast break better than our opponents were.