Chapter 10

Primary and Secondary Breaks

Mike D’Antoni, Alvin Gentry, and Marc Iavaroni

More than half our points are scored off our fast break. That includes both the baskets we make quickly off the initial offensive surge at our end of the court (primary breaks) and the baskets we score quickly afterward once all our players make it into the frontcourt, before the defense is able to fully recover (secondary breaks).

A successful running game starts not with Xs and Os but with a proper state of mind. Basketball is a game of reaction; players must react immediately to new situations and change instantly from defense to offense. Players don’t have time to think about where they should go or what they should do; they must simply respond in a flash. The rebounder who hesitates in throwing the outlet pass, or the guard who fails to anticipate and break to the pass to push the ball up the floor, will render what appears to be a perfect fast break on paper ineffective on the court. A “move it, now” mind-set is essential to the success of a breaking team.

The second prerequisite for the fast break is understanding how to run. That means as soon as we gain possession—or as soon as it appears we’ll gain possession—of the ball, we’re off to the sprints. The rebounder, or more likely the recipient of the outlet pass, should high-tail it up the court with the ball, looking for a free teammate further down the floor. Everyone else is sprinting to the offensive end. There should be no wasted motion. That’s easier to say than do because proper running and sprinting technique take a willingness to work and a high level of conditioning. Watching videos showing correct running mechanics and then practicing these techniques will help establish the basics; then it comes down to applying those same movements at full speed in game situations.

The simple part of instituting a running system is selling the players on it. Few athletes in today’s game want to walk the ball up the court and hold it for the full 24 seconds each possession. They want to play up-tempo—just as they play in full-court pick-up games when given the chance. The fast-break style appeals to players’ natural preference to make something happen, and quickly. The style is a lot of fun when it works. But what most players fail to appreciate, at least at first, is what it takes to execute a consistently effective, fast-paced, full-court offense.

Coaches are often reluctant to commit to a running-style game for fear of too many turnovers. That’s understandable; a helter-skelter-type break almost invariably leads to a high percentage of lost possessions, even before the team can attempt to score. In our system, however, we remain in control. In fact, our turnover total is among the lowest in the NBA, and is extremely low given the number of additional opportunities we create with the break.

In this chapter we’ll explain how we do it. You might be limited by the personnel of your team, or your league might have rules that limit your commitment to such a system, but even so, you’re sure to find many elements here to benefit your offensive attack.

Elements of the Break

Before getting into the specifics of how we run our primary and secondary breaks, let’s first look at the core components that make our style of play possible.

Personnel

Every team must have a good point guard who can see the whole picture on the court. Naturally, it helps if that point guard is Steve Nash, the two-time NBA MVP, who is like a second coach on the court. But not every point is going to have Steve’s tremendous court vision, superb passing skills, and fantastic ability to anticipate on the court. What’s essential, though, is that the point guard can read situations and pass the ball quickly with no wasted dribbling.

Nothing undermines a fast-break offense quicker than a point guard who fails to advance the ball upcourt or who misses an open teammate in position to score. Every player without the ball must be in motion, sprinting the court, cutting, and using screens—doing whatever it takes to get open. If a point guard fails to deliver the ball to teammates who are making such an effort, before long they’ll stop moving as quickly and persistently on the floor. When that happens, your fast break is effectively shut down.

To complement a capable point guard, successful running teams also have quick athletes who are totally committed to this style of play. Amare Stoudemire is one of the quickest power forwards in the NBA, and Leandro Barbosa is also very fast. Players with such quickness love the opportunity to use that asset, and the fast-break game creates those situations.

Conditioning

A high level of physical conditioning is mandatory for any team committed to running the fast break. All players, including reserves, must be in top shape and have the stamina to sprint the court from the opening tip to the final buzzer. For reaching the best possible shape, we run a lot in practice, and we do all our drills, on full- or half-court, at maximum speed, from the usual full-court break drills to shooting drills.

Defense

Fast-breaking teams are sometimes accused of playing poor defense. Critics point out that we allow opponents more points than other teams do and that our opponents’ field-goal percentages aren’t the best. What they neglect to mention is that we typically outscore our opponents by more points than almost anyone.

Our defense has to fit our running offense, so we’re not going to play a sit-and-wait, slug-it-out style favored by more physical, deliberate teams. When we play well defensively, we disrupt the opponent’s flow and create loose balls and turnovers that we can convert quickly into baskets. Our fast break is most productive when we’re aggressive on the defensive end, stealing the ball, stepping into the passing lane, contesting shots, and blocking out.

We harass the opposing offense, keeping them unsettled by the pace of our game and forcing them into taking bad shots. When that happens, they often miss, and then we’re off to the races. We’re dictating the action and making our opponent exert a great deal of energy in the transition game. The result is that we create more and better scoring opportunities for ourselves, taking our opponent out of its comfort zone and wearing it down over the course of the game.

Rebounding

Obviously, the more possessions you have, the more chances you have to run the fast break. The most common way to get the ball is to take the defensive rebound, which is easier said than done. All five players must be alert on every opponent’s shot and block out the offensive players; they need the strength of will to prevent opponents from getting into the paint and grabbing rebounds. This task is demanded not only of the big men but also of the guards and small forward—an example is small forward Shawn Marion, a great rebounder and among the best in the league.

Ball Handling

We strongly believe that every player, from the starting five to the last of our reserves, must have good ball-handling skills if we’re going to run a sound fast break. If the ball is in the hands of Nash the majority of the time on the primary or secondary break, there will be more than one occasion when the play requires our forwards and centers to drive when running the fast break. When we talk of ball handling, we include the skills of dribbling the ball at full speed as well as executing proper passes at proper times.

Shooting

When a player is free on a primary fast break, he has the green light to shoot. Yes, players must exercise good shot selection—taking shots within their range that they can shoot with confidence—but they must not hesitate to put the ball up when scoring opportunities present themselves. I get much more upset when players fail to shoot open shots than I do when they miss the shots (unless, of course, an open shooter passes to a teammate who has an even better shot).

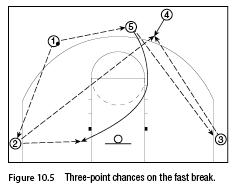

A signature of our break involves players spotting up on the three-point arc, ready to launch a shot. This feature really spreads the defense because the players who have hustled back to defend must decide whether to extend out to the perimeter or stay back in the lane to deny easy layups. Often we’ll catch defenders in no-man’s land, unsure of what to do, in which case our man on the arc can shoot, fake, and drive, or fake a shot and pass to a teammate in better position to score.

Ideally, every player on the team will have excellent shooting mechanics, but that’s rarely the case. Regardless of how much instruction they receive and practice they put in, some players are going to have idiosyncratic technical flaws in their shooting motion. That doesn’t always mean they’re incapable of shooting at a high percentage, especially if they’re consistent in their technique, release the ball quickly, and get decent elevation at release. Again, shot selection comes down to each player understanding what a good shot is for him.

Primary Break

A standard way of defining the primary break is the first two or three seconds a team has the ball after transitioning from defense to offense. This is when the opposing defense is most vulnerable. Once we gain possession, there’s no hesitation—we’re sprinting toward our end of the court.

We fast break on every possession in the following situations:

• A defensive rebound following a missed field goal or free throw.

• An out-of-bounds play, whether after a score or a violation. (Normally, the power forward is supposed to make the inbounds pass, but we don’t strictly follow this rule. Any player nearest the ball after an opponent’s score can make the inbounds pass if doing so gains us precious seconds in getting the ball upcourt.)

• A steal by the defense or a turnover by the offense.

Although a very fast player with good ball-handling and shooting skills might be called a “one-man fast break,” rarely is a team successful if it relies on a single player to convert in its transition game. Rather, the two most common primary break scenarios involve two offensive players and three or more offensive players on the attack.

Two-on-One Break

When two players fast break against one defender, the offensive players must keep good spacing between them, which is the secret of any fast break. This prevents the single player back on defense from covering both offensive players.

As the two offensive players move toward their basket, the ball handler should stop (but continue to dribble) near the corner of the free-throw lane, while the other offensive player, keeping proper spacing, cuts at a 45-degree angle to the basket (figure 10.1). At this point, it is up to the ball handler to read the situation and react based on what the defender does. If the defender moves out to cover him, the ball handler passes the ball to an open teammate. If the defender sags back or hedges toward the offensive player without the ball, the ball handler takes the open shot or drives to a point where an unimpeded shot can be taken.

We don’t have definite rules for players in our fast break except that they maintain proper spacing and an eagerness to run. Of course we try to correct them when they make the wrong decision on a two-on-one fast break, but we generally allow their court sense to determine the best option.

Break With More Than Two Players

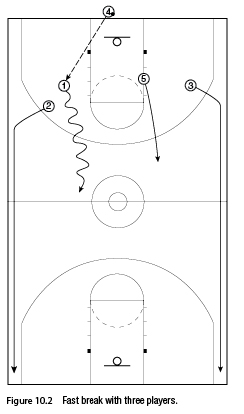

After a basket by the opponents, let’s assume that 4, the power forward, makes the inbounds pass to 1, the point guard, and the two other perimeter players—2, the shooting guard, and 3, the small forward—run as wide as possible (exaggerating, we tell them to “touch” the sideline to give them precise lanes to occupy) and go deep into the two corners of the offensive half-court (figure 10.2).

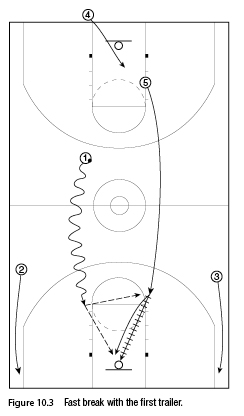

These three players must recognize that with the fast break they can go straight to the basket and score with a layup, but without the fast break there’s no advantaged situation in which the offense outnumbers the defense. In this case, the two wings run until they reach the baseline and then stay deep in the corners; in this set, the spacing is very important—you want to force the defenders to cover a wider area. 5, who is the first trailer (4 has made the inbounds pass and is the second trailer), sprints the floor, following the first three players on the fast break. 5 has two options:

• He can, once he reaches the free-throw line extended, receive the ball and shoot, or cut into the lane at a 45-degree angle and receive the ball for a shot under the basket (figure 10.3).

• He can stay in the middle of the floor to reverse the ball to the other side of the court.

In this second case, 1 moves the ball to an area in which he can take advantage of spacing and possibly pass the ball to 5 to try to score with a layup.

Alternatively, 4, a shooter who made the inbounds pass, sprints on offense and spots up for a three-point shot (figure 10.4). The players’ movements can also create the chance for a three-point shot by 2 or 3, who are spotted deep in the corner, or a shot by 5, who, in this case, is the first trailer (figure 10.5).

If there are no quick solutions on our primary fast break, we immediately run a pick-and-roll play. 4 sets a screen on 1, and they play a quick pick-and-roll. This action can create a situation in which 1 can pass to perimeter players 2 or 3, who are in the deep corners, for a three-point shot; 1 can pass to 5, who has cut into the three-second lane; 1 can make a layup; or 4 can shoot from the lane, rolling to the basket after setting the screen for 1 (figure 10.6).

Secondary Break

Our secondary break is in the hands of Steve Nash, who is an unbelievable passer and creator of scoring options for himself and his teammates. Again, such a player is the base of the success of our fast break.

We play our secondary break in a different way from other teams. We post up our centers and power forwards for no more than a few seconds because we want to take advantage of the quickness of our big men and their shooting skills from the outside. As you’ll notice, we always want to have at least three, if not four, players on the perimeter, and we give them the green light to shoot if they’re free. We also want to reverse the ball as quickly as possible to create open shots on the perimeter. Let’s now look at some of our plays generated from the offensive transition.

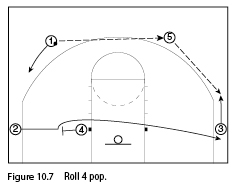

Roll 4 Pop

If in this case 4 is the first trailer and 5 is the second trailer, 4 cuts into the lane and posts up, while 5 stops outside the three-point line.

1 passes the ball to 5 and goes in the opposite direction; 5 reverses the ball, passing it to 3, who comes high. At the same time as the pass from 5 to 3, 2 cuts along the baseline, using the screen of 4, and then moves into the opposite corner, replacing 3 (figure 10.7).

If 3 can’t pass to 2, 1 screens down for 4, who comes high and receives a stagger screen from 5, who, after the screen, sets up in the short corner. 4 goes to the middle of the court and receives the ball from 3. 1, after setting the screen, returns to his original position (figure 10.8).

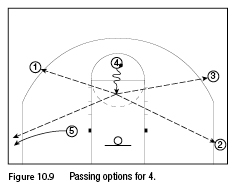

4 drives to the basket, where, if he can’t shoot, he kicks the ball to a teammate on the perimeter: either to 5, who pops out to the corner, or to 1, 3, or 2 (figure 10.9). At least one of these four players on the perimeter will be free for a shot.

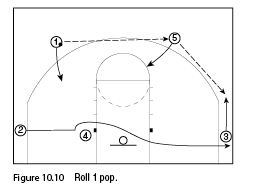

Roll 1 Pop

The play starts like the previous one but this time is run for 1. 1 passes to 5; 5 passes to 3, who comes high. At the same time as the pass from 5 to 3, 2 cuts on the baseline, using the screen of 4, and then moves to the opposite corner, replacing 3 (figure 10.10).

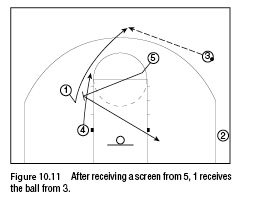

1, after the pass to 5, starts to cut down; this time he doesn’t screen for 4, but receives a screen from 5, goes high in the middle of the half-court, and receives the ball from 3. Right after the screen, 5 rolls to the basket and moves to the short corner on the other side of the court, while 4 goes to the angle of the free-throw area (figure 10.11).

1 passes the ball to 4, cuts around him for a possible hand-off pass, and then goes out to the corner. Meanwhile, 3 cuts into the lane and moves to the short corner on the other side of the court. 4, if he can’t shoot or drive to the basket from this position, drives toward 2 for a hand-off pass. 2 can penetrate or pass to 4, 5, 3, or 1 (figure 10.12).

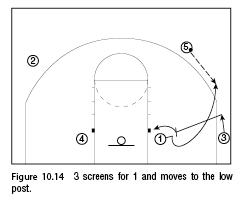

Through Flare 1 Man

Starting from our set after the offensive transition with 5 as the second trailer, 4 as the first trailer on the low post, and 2 and 3 in the deep corners, 1 passes the ball to 2, who comes high, or to 5, in this case, and then cuts to the opposite side of the court in the low-post area (figure 10.13). 3 screens for 1, who comes off the screen and receives the ball from 5. After the screen, 3 moves to the low-post area (figure 10.14).

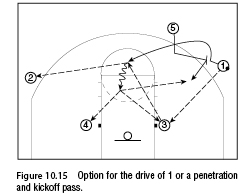

If 1 isn’t free to shoot, he passes the ball to 3, receives a screen from 5, goes to the middle of the court, and receives the ball back from 3. He can now drive to the basket or drive and kick off the ball to 2, 4, 3, or 5, who rolls after the screen (figure 10.15).

Practice

Running teams must run a lot during practice. This goes back to one of the basic aspects of the fast break, maintaining a running attitude, a state of mind that’s developed in practice.

We do some work on half-court in practice, but once the season starts we devote most of the 90 minutes to full-court running. Sometimes execution is sloppy, but we don’t want to compromise our running. Our style of basketball is based on quickness and speed, not on power and set plays, so our players must be able to react immediately to any defensive situation. This is why we practice all the possible plays of the secondary break at full speed.

We divide the team into perimeter players (point guards, guards, and small forwards) and big men (power forwards and centers). Our big men have different skills from most big men on other teams; they don’t post up much, but they can face the basket and also drive and shoot from the outside. One of our main offensive rules is that we want the middle of the court open.

In the following drills we’ll show how we work with our big men, while on the other side of the court, our perimeter players practice shooting off the different options of our secondary break.

Drills for Primary and Secondary Breaks

You cannot simply ask the team to run on offense if you do not run in practice and you do not practice the different solutions that will be applied on the court. Here are some simple drills we run to cover the different options on the break.

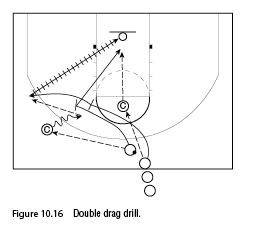

Double Drag

We set up one coach on one side of the half-court and another coach at the free-throw line, while a line of big men, each with a ball, are in the middle of the half-court.

The first player passes the ball to the coach on the perimeter; the second player passes the ball to the coach at the free-throw line. These two players then set a stagger screen (we call this a “double drag”) for the coach on the perimeter. The first player picks and rolls to the basket, receives a pass from the coach at the free-throw line, and shoots a layup or a dunk; the other player, after the second pick for the coach outside the three-second lane, pops out, receives the ball from the coach on the perimeter, and shoots from outside (figure 10.16).

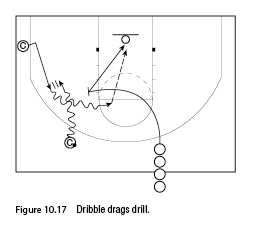

Dribble Drags

We set up one coach in the corner without the ball, one coach with the ball on the same side outside the three-point line, and one line of players. The coach with the ball starts to dribble toward the other coach, who comes high and receives a hand-off pass. The first player in line makes a screen for the second coach, then rolls to the basket to receive the ball from the second coach, who has dribbled around the screen (figure 10.17).

Rim Runs

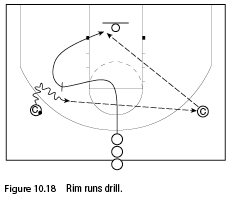

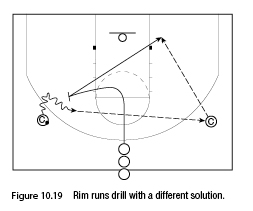

We set up one coach with a ball on a wing and another coach on the opposite wing, without a ball; players form a line in the middle of the half-court.

The drill starts with the coach with the ball dribbling toward the baseline and then receiving a side screen from the player at the front of the line. The coach goes around the screen and reverses the ball, passing it to the coach on the other side. After setting the screen, the player rolls to the basket on the side opposite the ball and receives a lob pass for a layup or a dunk (figure 10.18).

The same drill can be run with a different finish. The coach dribbles toward the baseline and receives a screen from the player, but this time, after the coach goes around the screen and reverses the ball to the coach on the other side of the court, the player cuts straight to the opposite short corner, receives the ball, and takes a jump shot (figure 10.19).

Read the Defense: Step Up

If the defense wants to force the ball handler to the sideline, we counter this defensive move with a step-up move. Following is the drill for practicing this move.

We run this drill on both halves of the half-court, with a coach with the ball on the wing and a line of players behind him. The coach starts to dribble to the baseline, and the first player follows him; then the player comes back and screens. After the screen, he rolls to the basket, going inside the lane, and receives the ball from the coach for a layup or a dunk (figure 10.20).

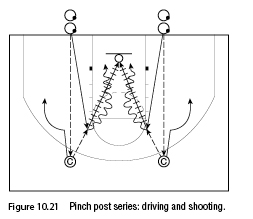

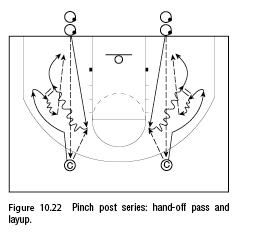

Pinch Post Series

We set up two lines of players at the baseline, facing the midcourt line. Each player has a ball. Two coaches are in front of the two lines.

The first player of each line passes the ball to the coach at the head of the line, then posts up at the corners of the free-throw area and receives the ball back; after the pass, the coach cuts around the player. While cutting around, the coach, acting as a defender, tries to hit the ball so that the offensive players must face a game situation. We run this drill with two finishes:

• The player drives right away to the basket for a layup or a dunk after faking a hand-off pass. As soon as the player receives the ball, he protects it, watching over his shoulder to get used to locating the defender, and then drives to the basket. Because two players are involved simultaneously, they must coordinate their drives to the basket.

• The player can also turn, face the basket, and make a jump shot (figure 10.21).

• The initial routine is as described before, but now the player receives the ball and dribbles outside the lane toward the coach, who after the pass has cut toward the corner. The player then makes a hand-off pass to the coach, who dribbles toward midcourt and passes the ball back to the player, who has rolled to the basket for a layup or a dunk (figure 10.22).

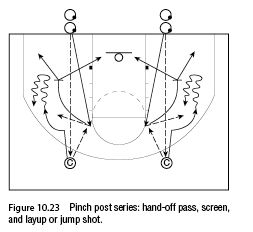

• The initial routine is as described before, but now the player makes a hand-off pass to the coach, who dribbles toward the baseline. The player then screens for the coach, who dribbles toward midcourt and passes the ball to the player, who, after the screen, can roll to the basket for a layup (or dunk) or to the short corner for a jump shot (figure 10.23).

Final Points

We’ve discussed the primary and secondary breaks, the practices, and the drills, but we would now like to say a few words about the foundation on which to build your running game—that is, all players must be in superb physical condition and have the proper mental approach.

We have spoken of endurance, stamina, and strength—all physical skills that a player builds through hours of conditioning on the court and in the weightlifting room. As we mentioned, we run all-out in practice; we do everything at full speed to build up the conditioning necessary to run for an entire 48-minute NBA game.

Yet you create this style of play not only through conditioning and drills but by talking to your players, giving them examples to follow, designating leaders who are totally committed to the running game, and instilling the idea that every player on the court will have a chance to score as long as he trusts this style of play. In short, you need to work on the physical and technical aspects of the fast-break game, yes—but you must also tend to the mental side. You must motivate your players to buy into this system. Once they do, they’ll find it’s an effective and exciting way to play basketball.