Chapter 12

Out-of-Bounds Plays

Brendan Malone

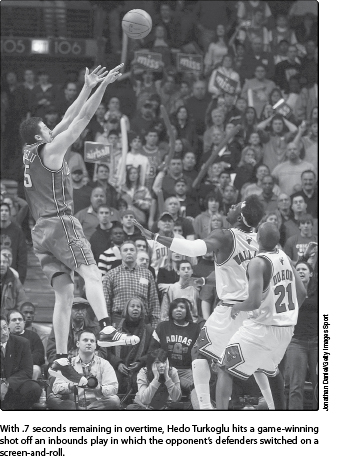

Well-executed out-of-bounds plays, as well as other special-situation plays, can be critical because late in a game they often make the difference between a win and a loss. All NBA teams run several of these plays, practicing them until they are automatic. Another name for the out-of-bounds play is the inbounds play.

There are keys to success at every level of basketball, but two stand out in our league. One such key is detail, which applies to individual fundamentals as well as to team offense and defense. Maybe more than any other team sport, basketball is a game of details, as well as of finesse and strength. A player might miss a shot by a fraction of an inch, costing his team the game. A screen set at a slightly improper angle won’t be effective in freeing up your shooter for his shot. A pass that is a trace too slow or barely off target will likely result in a steal. When it comes to running out-of-bounds plays, detail is as important as ever. When a team is working on the fundamentals necessary to run a baseline or sideline out-of-bounds play, the coach must attend to every detail.

Another key is execution. To perfectly execute a play, and to know that the play will be executed perfectly every time, teams must practice the play over and over until it becomes automatic. Never assume that players will run a play in a game properly after they’ve practiced it only a few times. Execution doesn’t come naturally to all players. You must run the play initially at moderate speed without the defense, then with the defense playing at 50 percent, and finally with the defense playing as they would in a game.

Run each out-of-bounds play many times during each practice. Players must have complete knowledge of the entire play. They must master the play’s first option as well as all the other options. They also must master the timing of the different actions of each option.

As coach, you need to make sure every player understands not only how to run the out-of-bounds play but why to run it; you want the skills of the play to be automatic, but you don’t want your players to play like robots. You want smart players who are conscious of the reasons behind each play. But before inserting and teaching specific plays, it’s useful to specify to players what you consider the keys to making your team optimally successful in such situations.

Basic Concepts

Before we get into each play, I want to emphasize some concepts I feel are important in the effective and successful execution of the out-of-bounds play.

• Get the ball inbounds. This is top priority. The inbounder can’t waste time or commit a turnover because he has locked into a single idea for the inbounds play. He needs to get the ball into the court, be it underneath or outside of the lane—this is the first aim of the play!

• Make your best passer your inbounder. The inbounder must pass the ball into the court with speed and accuracy, preferably to particular teammates, so use your most reliable passer for the best execution of the inbounds play. If your best passer is out of the game, designate a player who handles the ball a lot, usually a 2 man or a 3 man. Your inbounder should always be the best passer you have on the court at the time.

• Your best scorer should be the first option to receive the pass. Don’t use your best scorer as the inbounder. This player should be the first option to receive the inbounds pass. Your team’s best shooters must get into position to receive the inbounds pass in the right spot when the passer is ready to inbound the ball.

• Use fakes. The inbounder will be aggressively pressured and in many cases should use pass fakes and other deception to get the ball inbounds. The inbounder might fake a pass up and then throw a bounce pass; he might fake a bounce pass and then make a pass over the top. He should also use eye and head fakes to throw the defender off, looking in one direction and passing in the other.

• Make good screens. You’ll usually use your big men to set screens and get their teammates open. But you can also use your 2 or 3 man to screen your big man or to force a defensive switch, or in screen-the-screener action to get the ball to the 2 or 3 man for shooting. The player who receives the screen must set up his defender. Meanwhile, the screener should screen a body, not the air, and, after the screen, he must step to the ball. Two other important points: Remind your players that the screener will always be freer than the teammate who is screened for, and make sure the screened player waits for the screen and doesn’t rush his shot.

• Screen the screener. This action is common in the NBA but is especially effective in inbounds situations. “Screening the screener” simply means that the player who first makes the screen then receives a screen himself. In most cases, the screener’s defender won’t have time to react to the second screen.

• Back screener will always be open. In certain situations, such as at the end of a game when opponents put a lot of pressure on your best shooter, the player who sets the back screen is always open. This player might become your first option—the player who gets the shot—or, if he can’t shoot, have him play pick-and-roll.

• Don’t panic. The inbounder must keep his poise. He should be counting, and if he can’t make the inbounds pass by the count of three, he should call a time-out. If no time-outs are left, he should throw the ball off a defender’s leg.

Calling the Plays

Different teams have different names for their inbounds plays. Some teams use the name of another team (New York, Indiana, and so on); other inbounds plays might be called a “quick,” “special,” or “home-run.” Sometimes numbers are used to indicate the player or players involved. For instance, if we call “53,” it means the play is run for our big man, 5, and our small forward, 3; if we call “42,” the play is run for our power forward, 4, and our 2 guard.

An out-of-bounds play can occur during a game or after a time-out. In either case, the coach calls a particular play, and the inbounder communicates the call to his teammates.

Remember that repetition and close attention to details will ensure the flawless execution of your out-of-bounds plays.

Baseline Out-of-Bounds Plays

In the NBA, most out-of-bounds plays are against a man-to-man defense, so most of the plays described here reflect that. On page 202, we show one play versus a zone defense.

“Series” Plays

The first play I want to introduce is one we call “series,” which includes sequences designated by an action and a number. The first number designates the receiver of the inbounds pass, and the second number designates the receiver of the guard-to-guard pass. The action is designated by the second part of the call and will be explained soon. It’s not imperative that we line up in the same spots each possession, but we must get to the proper spots to receive the inbounds pass and execute the action.

The first number (the receiver of the inbounds pass) catches the ball in the “catch area,” which is an area around the elbow extended on the side of the inbounder. The second number (the receiver of the guard-to-guard pass) catches the swing pass even with the catch area on the opposite side of the free-throw lane.

The proper receiver must make himself available to receive the ball in the proper area at the time the passer is ready to make the pass. Also understand that the pass doesn’t have to go directly to the catch area from the out-of-bounds pass. If the defense prevents this pass, the ball can go through the corner to the catch area and you’ll still have the same option.

Here are the different action sequences for “series.”

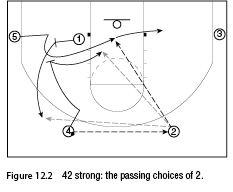

42 Strong

1 is the inbounder; the other four players are set on a flat formation on the baseline: 5 and 3 are near the sidelines on the corners; 4 and 2 are on the low-post areas above the blocks.

4 (the receiver in the “catch” area) fakes to go to receive the ball from 1 and then pops up toward the midcourt line and outside of the three-point line. 2 (the receiver of the guard-to-guard pass) makes the same movement. 1 passes the ball to 4 and then enters the court and replaces 4 (figure 12.1).

4 swings the ball to 2; 5 comes off the shuffle screen of 1; 4 screens the screener, 1; and 2 has the following choices:

• pass to 5,

• pass to 1, or

• pass to 4, who rolls to the basket after setting the screen for 1 (figure 12.2).

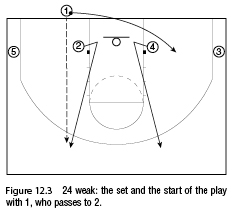

24 Weak

The set is similar to the previous one, but now 4 and 2 invert sides and roles: 2 receives the pass in the catch area, and 4 receives the guard-to-guard pass; 1, after the pass to 2, enters the court and replaces 4 (figure 12.3).

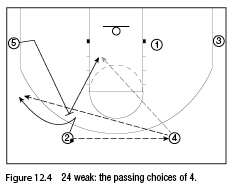

Now 2 swings the ball to 4, and 5 sets a flare screen for 2. 5 reads the defense—if his defender jumps out, he slips the screen and cuts to the basket (figure 12.4). 4 has the following choices:

• pass to 2, or

• pass to 5, who slips the screen or rolls to the basket after setting the screen for 2.

43 Counteraction

The set is similar to the previous one, but now 2 and 5 are in the corners near the sidelines and 3 and 4 are on the low-post areas above the blocks. 4 pops up and receives the inbounds pass in the catch area. 3 also pops out to take his defender high, while 1 enters the court and goes out to the three-point line. 3 then makes a backdoor cut to receive a lob pass from 4 (figure 12.5).

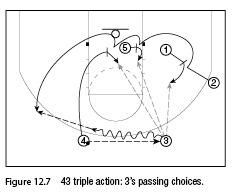

43 Triple Action

The set is similar to the previous ones, but now 5 and 2 are near the sidelines above the blocks, and 4 and 3 are on the low-post areas, with 4 the receiver in the “catch” area, and 3 the receiver of the guard-to-guard pass.

4 pops out over the three-point line and receives the inbounds pass from 1, while 3 also pops out over the three-point line. After the pass to 4, 1 enters the court and cuts opposite to the ball (figure 12.6).

1 screens for 2, who cuts into the lane and receives another screen from 5. 4 swings the ball to 3 and cuts down to the lane to make a third screen for 2, who pops out over the three-point line. 3 dribbles toward 2 and either passes 2 the ball or chooses one of these options (figure 12.7):

• pass to 4, who goes to the ball after the screen,

• pass to 5, who rolls to the basket after the screen, or

• pass to 1, who opens up to the ball after the screen.

24 Weak Dive

The set is similar to the previous ones, but now 2 and 4 are on the low-post areas above the blocks, with 2 the receiver in the “catch” area, 4 the receiver of the guard-to-guard pass, and 5 and 3 near the sidelines.

2 pops out over the three-point line and receives the inbounds pass from 1; 4 pops out over the three-point line (figure 12.8). After the pass to 2, 1 enters the court and replaces 4.

2 swings the ball to 4; 5 sets a flare screen for 2. On the pass over the top from 4 to 2, 4 dives to the basket to receive the ball from 2. 2 can also pass to 5, who, after the screen, rolls to the free-throw area (figure 12.9).

Stack Plays

One common offensive set in the NBA is the stack, in which two or three players are lined up in a straight line, either perpendicular or parallel to the sideline. This special set is often used and recommended for out-of-bounds plays. Here is a series of plays that start from this formation and have different solutions.

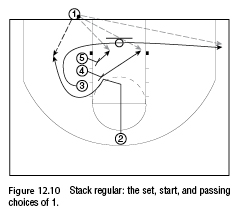

Stack Regular

1 is the inbounder; 5, 4, and 3 line up in the stack formation on the left side of the court parallel to the sideline; 2 is at the top of the key. 3 curls around 4 and 5, rubbing off 5’s shoulder, and goes to the opposite corner, outside of the arc of the three-point line. As soon as 3 curls around 5, 2 fakes a cut to the middle of the lane and then uses the double screen of 4 and 5 to go to the midpoint outside the lane (figure 12.10). 1 has the following choices:

• pass to 2 on the curl,

• pass to 3 in the opposite corner, or

• pass to 4 or 5, who roll to the basket in opposite directions after setting the double screen.

Option. If 2 receives the ball and doesn’t have a shot, 5 goes to the low-post area opposite of the stack; 4 plays pick-and-roll with 2; 1 enters the court, rubs off 5’s shoulder, and goes outside the arc of the three-point line (figure 12.11). 2 now has the following choices:

• shoot, using the pick of 4, or drive to the lane;

• pass to 4, who after the screen rolls to the basket;

• pass to 1;

• pass to 3 in the corner; or

• pass to 5, who ducks into the lane.

If 1 receives the ball, he has these options:

• shoot,

• pass to 5 in the low post, or

• pass to 3 in the deep corner.

Stack Special 1

Now let’s look at some options to the regular stack. As said before, on every play a coach must have options based on the reactions of the defenders. The initial set here is the same as described for the stack regular: 1 is the inbounder; 5, 4, and 3 form the stack; and 2 is at the top of the key. After 3’s curl, 5 screens for 4, 4 pops out, and then 5 screens again, this time for 2, and rolls to the basket (figure 12.12).

1 has the following choices:

• pass to 3 on the curl;

• pass to 4, who has popped out to the corner;

• pass to 2, who has cut into the lane; or

• pass to 5, who has rolled to the basket after the screen.

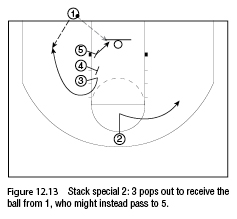

Stack Special 2

Starting from the same set as just described, this time 3 doesn’t curl around the stack but pops out to receive the ball from 1. 1 might instead pass the ball to 5, who’s rolling to the basket after the screen (figure 12.13).

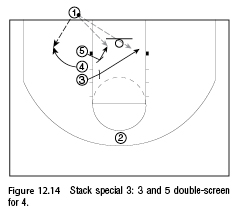

Stack Special 3

The starting set is the same as before. Here 3 doesn’t cut into the lane. Rather, 3 and 5 pinch in and screen for 4, who pops out to the corner to receive the ball from 1. 1 might instead pass to 5 or 3, who roll to the basket in opposite directions (figure 12.14).

Golden State

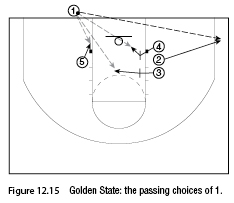

In this play we still form a stack but opposite to the ball and with different players. 1 is always the inbounder; 4, 2, and 3 set a stack formation on the right side of the court; and 5 is on the left low post, facing the ball.

2 pops out of the stack to the corner, while 4 and 3 squeeze the defenders, forming a double pick. 1 passes the ball right away to 2 for a three-point shot, or to 4, who rolls to the basket after the screen (figure 12.15). 1 can instead pass to 5, who’s cutting to the basket, or to 3, who’s rolling opposite to 4.

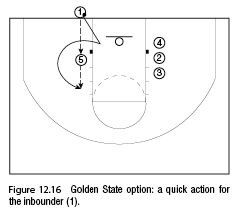

Option. With a few seconds left on the clock, after the inbounds pass directly to 5, 1 enters the court and cuts off 5 after faking away. 5 passes the ball back to 1 for a quick shot (figure 12.16).

Indiana

I call this play Indiana because when I was assistant coach with the Indiana Pacers, we ran this set with a high rate of efficiency for Reggie Miller or Jalen Rose. You might recall Miller as one of the best outside shooters ever to play in the NBA.

Start in a flat formation on the baseline. 1 makes the inbounds pass; 5 is at the low post; 4 is at the low-post position opposite to 5; 2 is under the basket; and 3 is in the opposite deep corner on the same side as 4.

2 comes out of the lane using the screen of 5, goes to the deep corner, and receives the ball from 1. After the pass to 2, 1 enters the court, is screened by 5, goes high, and receives the ball from 2 for a shot (figure 12.17). 2 can also pass to 5, who has rolled to the basket after setting the screen for 2.

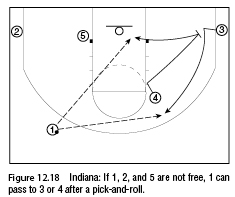

On the pass from 1 to 2, 4 goes out of the lane opposite to the ball and screens down for 3 in the corner. 1 can pass to 3, who comes off the screen of 4, or to 4, who rolls to the basket after the screen (figure 12.18). After we ran this play a few times, we were able to give the ball right away to 3 (or to 2 in the corner) because all the defenders jammed the three-second lane (figure 12.19).

New York

In this play, 3 is the inbounder, 5 is at the low post, 2 is in the opposite low-post position, 4 is at the corner of the free-throw area on the same side as 5, and 1 is set up above the three-second lane, making himself available as a safety. 2 screens for 4, and then 5 screens 2 in screen-the-screener action (figure 12.20). 3 has the following choices:

• pass to 4, who is screened for by 2;

• pass to 2, who cuts to the strong-side corner off the screen of 5; or

• pass to 5, who rolls to the basket after screening for 2.

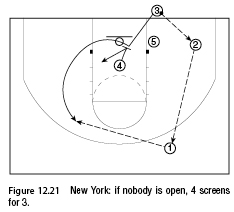

After he has received the screen from 2 and can’t receive the ball, 4 goes down and screens for 3, who, after the inbounds pass to 2, has entered the court. 2 passes to 1; 1 passes to 3, who comes off the screen of 4 (figure 12.21). 3 can then pass back to 4, who is rolling to the basket after the screen.

I remember a game when I was on the bench with the New York Knicks. We were down by three points at the end of the game, and we called this play (though it had a different name then). 1 was completely free at the top of the key, and Hubie Brown, our head coach, yelled to pass directly to 1 for a three-point shot. That tied the game. In fact, all the defenders, recognizing the play, were so worried about jamming the lane that they failed to cover 1.

25

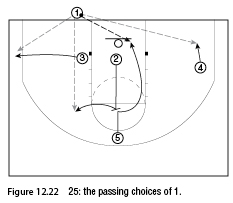

This play is run for 2, the shooting guard, and 5, the center. 1 is the inbounder; 2, the best scorer, is under the basket; 3 is at the midpoint of the three-second lane; 5 is at the top of the lane, inside the three-point line; and 4 is outside the lane on the right side.

2 screens for 5, who cuts to the basket (the big men are not accustomed to being screened, so this move can surprise them). On this type of screen, very seldom is there a switch because a smaller player cannot guard a big man, so 5 is left open.

3 pops out to the three-point line in the corner. 2, after setting the screen for 5, pops out on the ball side (figure 12.22). 1 has the following choices:

• pass to 5, who cuts off the screen of 2;

• pass to 2, who pops out after the screen;

• pass to 3, if his defender helps out on 5; or

• pass to 4, who has spotted up on the other side of the court.

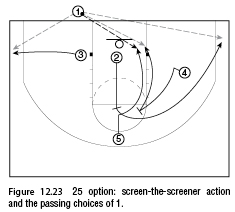

Option. The set is the same as just described, but on this option, while 3 pops out in the corner, 2, after setting the screen for 5, receives a screen from 4 (screen-the-screener action) and then pops out at the three-point line. After the screen, 4 rolls to the basket (figure 12.23).

1 has the following choices:

• pass to 5, who cuts off the screen of 2;

• pass to 2, who receives the screen from 4 and then pops out;

• pass to 3, who pops out in the corner; or

• pass to 4, who is rolling to the basket after setting the screen for 2.

Now I would like to show two inbounds plays particularly designed for the big men: 4, the power forward, and 5, the center.

54

3 sets up on the low post near the baseline on the same side as 1, the inbounder; 4 is at the corner of the free-throw area on the ball side; 5 is in the low-post area, opposite to 3; and 2 is set up outside the three-point line, opposite the ball.

3 pops out in the corner to take away the help; 5 makes a diagonal screen for 4, who cuts into the lane; 5 rolls to the basket after the screen; and 2 spots up on the ball side (figure 12.24). 1 has the following choices:

• pass to 4, who cuts off the screen of 5;

• pass to 5, who rolls to the basket after setting the screen for 4;

• pass to 3, if 3’s defender helps on the roll of 5; or

• pass to 2, who spots up for a three-point shot.

Quick 2

The action and the set are similar to the previous drill but this time involve mainly the guard (2) and the center (5). 1 is the inbounder; 4 is at the low post on the left side of the three-second lane, on the same side as the ball; 5 is on the low post on the right side of the three-second lane; 2 is at the corner of the free-throw area, facing the ball; and 3 is outside the arc of the three-point line. 5 screens diagonally for 2 and pops out, while 4 pops out of the low post and goes to the corner (figure 12.25). 1 has the following choices:

• pass to 2, who rubs off the screen of 5;

• pass to 5, who, after the screen for 2, pops out;

• pass to 4, if 4’s defender helps on 2’s cut; or

• pass to 3, who spots up for a three-point shot.

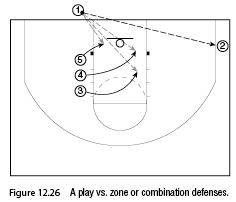

Baseline Out of Bounds vs. Zone or Combination Defenses

1 is the inbounder; 5, 4, and 3 form a stack parallel to the sideline near the lane on the ball side; and 2 spots up in the opposite corner for a potential direct pass. 5 and 4 cut into the open gaps of the zone while 3 cuts to the open area in the middle of the three-second lane. The cuts of 5, 4, and 3 shrink the zone defense, which enables 1 to make a direct pass to 2 in the corner (figure 12.26).

Sideline Out-of-Bounds Plays

Let’s now look at some sideline out-of-bounds plays, another basic aspect of the game that every coach at every level must be ready to face—but especially in the NBA, where many games are won or lost by 1 or 2 points.

End of the Game or Quarter Plays

The following plays are used on the sideline and when there are few seconds left on the clock at the end of the game or a quarter. This situation can give a definite advantage to the team on offense, because the opposing players are not accustomed to facing plays that are not run throughout the course of the game, and a basket scored on one of these plays can be crucial at the final buzzer.

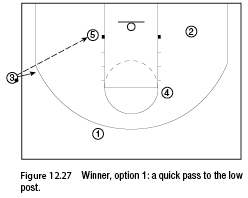

Winner

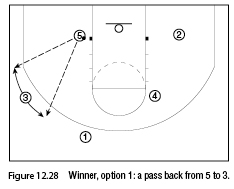

Option 1. 3 is the inbounder; 5 is at the low post, ball side; 1 is outside the three-point line; 4 is at the elbow opposite the ball; and 2 is opposite to 5 and outside the lane. The easiest option is a direct pass to 5 for a quick shot (figure 12.27). If 5 receives the ball but can’t shoot, 3 steps inbounds to receive a pass back from 5 for a three-point shot (assuming you need a three-pointer to win the game) (figure 12.28).

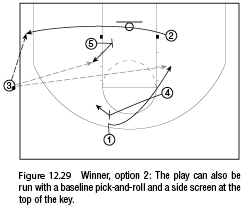

Option 2. 3 has the option to pass the ball to 2, who cuts into the lane, gets a screen from 5, goes out past the three-point line (assuming you need the three-pointer), and shoots. If you need a two-point shot, 3 can pass to 1, who is screened by 4, or to 5, who rolls to the basket (figure 12.29).

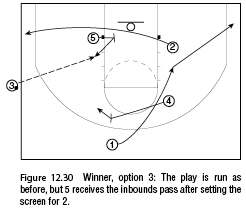

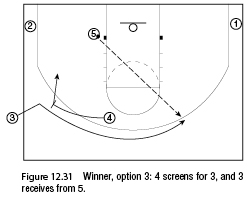

Option 3. The play is run as before, but this time after setting the screen for 2, 5 rolls to the ball and receives the inbounds pass from 3 (figure 12.30). Right after the pass, 3 steps inbounds and receives a screen from 4, and 5 passes the ball to 3 for a three-point shot (figure 12.31).

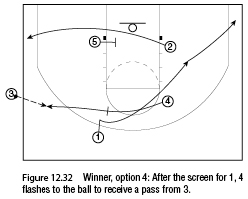

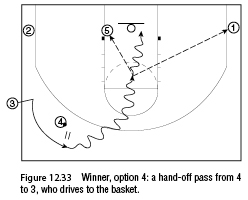

Option 4. 4 screens for 1, who goes to the corner, and 4, immediately after the screen, cuts to the ball and receives from 3, while 2 cuts to the other side of the court and is screened by 5 (figure 12.32). 5 can then roll to the basket. 3 passes to 4 and cuts off him; 4 hands the ball off to 3, who drives to the basket, looking to score or to kick the ball off to 5 on the low post, or to 1 in the corner (figure 12.33).

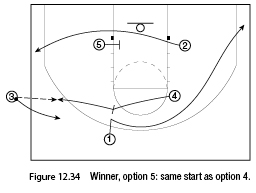

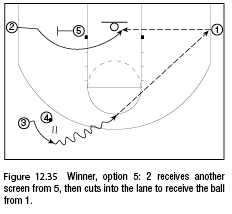

Option 5. 4 screens for 1, who goes to the corner away from the ball. 4, immediately after the screen, cuts to the ball (figure 12.34). 3 passes the ball to 4, who hands the ball off to 3; 3 passes the ball to 1 in the corner, and 1 passes to 2, who receives a screen from 5 and cuts into the lane (figure 12.35).

Hook

The following plays were created by Chuck Daly, who won two NBA championships as coach of the Pistons. He was also coach of the original Dream Team, which won the 1992 Olympic Games. This was one of his favorite sideline out-of-bounds plays when he needed a basket at crunch time. 3 is the inbounder; 4 and 5 set up outside of the free-throw elbows; 1 is near 4 on the ball side; and 2 is under the basket. 4 screens for 1, and 1 cuts off the screen and goes to the deep corner, ball side. At the same time as 4’s screen for 1, 5 screens for 2, trying to set the pick at a certain angle. 2 comes out to the three-point line. As soon as 1 cuts off the screen, 4 pops out to receive the ball from 3. 4 passes to 2, who can shoot a two- or three-point shot. If 2 can’t shoot, he passes the ball to 5, who has frozen his defender under the basket after setting the screen for 2 (figure 12.36).

X

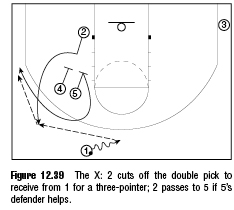

4 is the inbounder; 3 and 2 are set up outside of the three-point line; 5 is at the top of the key; and 1 is under the basket. 3 and 2 cut off 5; 2 sets up at the low-post position, ball side, and 3 goes to the opposite corner (figure 12.37). Right after the cuts of 3 and 2, 5 turns and screens down for 1, who comes up and receives the ball from 4. After the screen, 5 cuts back to the ball as a safety valve in case 4 can’t pass to 1. Right after 1 has received the ball from 4, 4 and 5 start to move to set a double pick inside the three-point line (figure 12.38).

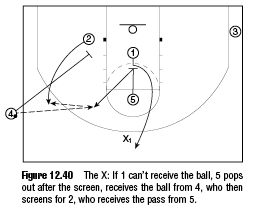

4 and 5 set a double screen for 2, who receives from 1 for a three-point shot. If 5’s defender helps out on 2, 5 cuts to the corner to receive the ball and shoot a three-pointer (figure 12.39). Naturally, not all teams have a post and a power forward able to shoot from the three-point range, so change the role of your players as necessary. If your 5 is not a good three-point shooter, have your 4 set the down screen for 1 instead of 5. If you don’t have a 4 or 5 that can shoot from the three-point arc, have a small forward inbound the ball. If 1 is denied the ball, 4 passes to 5, who has popped out after the screen, and then screens down for 2, who receives the ball from 5 to shoot (figure 12.40).

Line

3 is the inbounder; 5, 4, 2, and 1 are set in a straight line parallel to the baseline at the free-throw line. 1 cuts off 2, 4, and 5, looking for a pass from 3, but 1 is rarely open. After the cut, 1 goes to the deep corner on the weak side. After 1’s cut, 2 brings his defender down into the lane and then cuts back off the double screen set by 4 and 5, looking for a pass from 3 (figure 12.41). If 5’s defender shows to help on 2’s cut, 5 cuts to the basket to receive the ball and shoot a layup (figure 12.42).

If the ball is inbounded by 3 to the deep corner, you can still run this play. The only thing that changes is the angle of the line, which will be at about 45 degrees to the corner on the ball side and is formed by four players. With 5, 4, 2, and 1 lined up in this order, 1 cuts around 2, 4, and 5, looking for a pass from 3 (figure 12.43).

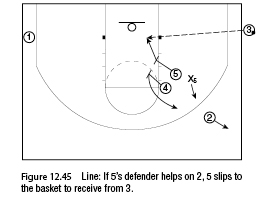

If 1 doesn’t receive the ball, he goes to the weak-side corner. The second option is the pass to 2, who, after having brought his defender down into the lane, cuts off the double screen set by 4 and 5 (figure 12.44). Finally, 3 can also pass to 5, who rolls to the basket if his defender steps out to help on 2, or 3 can pass to 4, who pops out after setting the screen for 2 (figure 12.45).

C

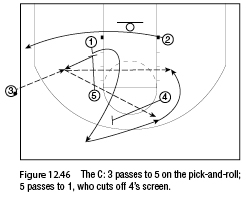

This is another play for when you need a basket late in the game. 3 is the inbounder; 1 and 2 are at the low-post positions; and 5 and 4 are at the elbows of the free-throw area, 5 on the ball side and 4 on the other side in a box set. 2 clears out to the opposite corner; 5 screens down for 1, who cuts off the screen and out to the three-point line; 5 rolls to the ball and receives from 3. At the same time, 4 screens for 1, who receives the ball from 5 for a three-point shot or a drive to the basket (figure 12.46).

Corner

3 inbounds the ball from the deep corner, always starting from a box set—this time with 1 on the ball side and 2 on the weak side. 2 clears out to the corner; 1 sets a diagonal back screen on 5’s defender; and 4 sets a screen on 1’s defender (screen-the-screener action). 3 can pass the ball to 1 or 5 (figure 12.47).

Argentina

This play was not taken from any NBA team playbook, but other NBA coaches and I had the chance to watch it at the 2002 FIBA World Championship in Indianapolis. We were impressed. 3 is the inbounder; 1 is on the weak side; 4 and 2 are at the low post spots; and 5 is on the high post, ball side. 2 back-screens for 5, is screened for by 4, and goes out to the three-point line. 3 passes the ball to 2 for the three-pointer (figure 12.48).

San Antonio

I watched the San Antonio Spurs run this play to win a game. 1 is at the low post, ball side; 5 is out of the lane; and 4 is at the elbow of the free-throw area on the same side as 5. 4 and 5 make a stagger screen for 2, who cuts out to the three-point line. 3 can pass to 2 for a wide-open shot. If 5’s defender helps out, 5 rolls to the basket to receive from 3 and shoot (figure 12.49).

Short Clock (1 or 2 Seconds Remaining)

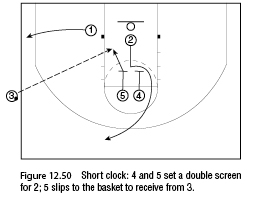

3 is the inbounder, 1 is at the low post, 2 is under the basket, and 5 and 4 are at the free-throw line. 5 and 4 set a double screen in the lane for 2, who cuts high out to the three-point line; 1 pops out to the corner, ball side. Right after setting the double screen, 5 rolls to receive from 3 and shoots under the basket (figure 12.50).

Short Clock 2

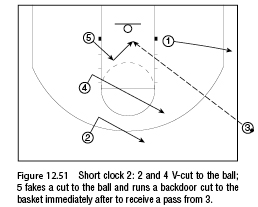

1 is at the low post, ball side; 5 is on the weak-side low post; 4 is at the elbow of the free-throw area; and 2 is outside the three-point line. This action all occurs at once: 1 cuts to the ball; 4 and 2 make V cuts to the ball; 5 cuts first to the free-throw line and then backdoor to the basket; and 3 makes a high lead pass at the rim to 5 (figure 12.51). The 5 player must be tall and able to catch a tough pass.

Three-Quarter Court Sideline Out-of-Bounds Plays

Following are two plays to run against a three-quarter press, one of the many defensive situations an NBA team, but also a team at the high school or college level, could face and must be able to beat.

Line Play vs. Three-Quarter Court Pressure

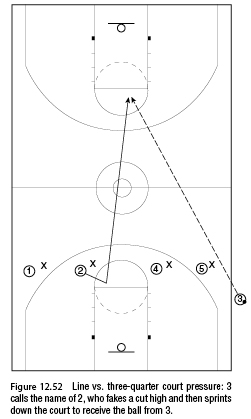

3 is the inbounder; 1, 2, 4, and 5 form a line outside the lane parallel to the baseline. 3 calls the name of one of his teammates (2, in this case), who fakes to cut high but then sprints to the basket to receive a long pass from 3 to shoot the layup (figure 12.52).

X Play vs. Three-Quarter Court Pressure

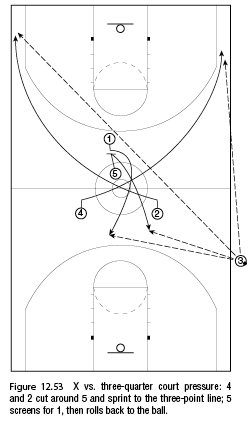

3 is the inbounder; 4 and 2 set up outside the three-point line; 5 is in the midcourt; and 1 is at the other half-court near the three-point line. 4 and 2 cut around 5 and sprint to opposite corners. Right after 4 and 2 are past him, 5 screens down for 1, who comes high. 3 can pass to 4 or 2 (figure 12.53). After the screen, 5 rolls back to the ball. 3 can also pass to 5 or 1.

Final Points

Depending on personnel and game situations, a coach can change the inbounder and the receiver of the passes. For example, if his best three-point shooter is a small forward (3), he can designate another player as the inbounder and 3 as the receiver of the pass for the shot. In short, the coach adapts the inbounds play to the skills of his players.

During my career I noticed a common mistake coaches make, so I’ll share it with you by way of closing remarks: Don’t take for granted that any play you watch and then adopt for your team will work as well for you as for the team you first saw use it. Very few coaches prove to be basketball geniuses, and while you can benefit from taking some ideas from others, remember that you must also be intelligent enough to evaluate whether certain plays really fit the skills of your players.

One final comment: Don’t complicate your life and the lives of your players. Using strange and difficult inbounds plays is usually not wise for several reasons. Fatigue, stress, crowd noise, game momentum, and, above all, your opponents can all affect a play’s dynamic, and when all these factors come together, as they often do, the last thing you need is to try something complicated. Sometimes the KISS rule (keep it simple, stupid) should override all others.