Chapter 14

On-the-Ball Pressure

Mike Fratello

The phrase “defense wins championships” applies to all levels, from high school through college to the pros. For our purposes in this chapter, defense means to aggressively attack an opponent’s offense, harassing and disrupting its every move.

Playing defense requires being extremely active. It means generating pressure on the offense, acting rather than reacting, looking to force turnovers, trying to confuse the offense and keep them off balance, and not waiting for mistakes to occur but creating them through aggressive, disruptive pressure.

To establish a defensive foundation for his team, a coach must consistently preach, teach, and be firm on this basic aspect of basketball. Defense is not a play a coach invents during a time-out or as a desperation move—it is a constant practice after practice, game after game, and season after season.

Rules for Building a Defense

To build a defense, you want precise rules that are easy to understand. Establishing individual defensive rules strengthens the importance of defense. Here are my building blocks for a pressure defense:

• Force the dribbler to make as many turns as possible, blocking his complete view of the court and making him lose time. This disrupts the flow of the offense, forces delays at the beginning of the play, and presents the defense chances to trap the ball handler.

• Don’t give an easy path to the basket to the player with the ball; always stay between him and the basket. If the defensive player on the ball handler is beat, all other defenders must rotate to stop the drive, which can create easy shots for the opponents.

• Pressure the ball as long as it’s in the hands of the offensive player; this means pressuring the dribble and also the pass. Pressuring the ball handler and contesting the pass means preventing the ball from getting inside the lane and taking away high-percentage shots.

• In general, force ball handlers to the sideline to block their view of the court and limit their passes to one direction. (Depending on the situation, you sometimes might want to force the ball handler to the middle.) If the defense keeps the ball on one side of the court, the ball handler stops or delays the quick reversal of the ball to the other side of the court. This is a great advantage because the reversal of the ball can create the problem of closeouts for the defenders on the weak side and rotation.

• Take away as many strengths of the opposing player as possible. Force the offensive player to shoot if he’s a nonshooter, to dribble with his weak hand, or just to dribble if he’s not a great ball handler. Basketball is a game of moves and countermoves; if you’re clever enough to take away the most dangerous moves of your assigned offensive players, you’ve done half your job.

• Remember that a defender is responsible for one offensive player and a half: his own assigned offensive player and “half” of the player assigned to the teammate nearest him. Each defender must understand he’s part of a defensive system, and his job is not only to stop his assigned offensive player but also to be part of a collective defense. The defender must always be ready to help, taking a charge whenever possible as well as blocking out and rotating as necessary.

Four Foundations for Building the Defensive Wall

Playing defense is like building up a wall between the offense and the basket. To build the wall you start with four foundations: mental skills, physical skills, technical skills, and communication.

Mental Skills

An offensive player must have skills such as passing, dribbling, and shooting. Playing defense is more a state of mind, but some individual and collective fundamentals are involved.

Any player—small or big, quick or slow—can play defense. He needs no particular physical assets but only these mental skills that any player can develop:

• Aggressiveness (but also control)

• Strong will to never give up

• Determination to give 100 percent

• Individual and collective pride and motivation

• A big heart

• Enthusiasm (which is contagious)

• Court intelligence to help read and react to the offense

• The desire to help a teammate who’s been beaten

As I’ve said, playing defense requires a total commitment from all players on the team. A coach must reach this goal by practicing all phases of defense: stance, foot movement, strong- and weak-side positioning, and rotations. Talk constantly, challenging and motivating your players to be the best they can be on defense. Set goals for each player as well as for the team. Goals give an exact vision of what you intend each player and the team to accomplish.

Individual Goals. Having all players, starters and reserves, keep a defensive goal in mind helps build both individual defensive pride and team pride. These are some of the defensive goals a coach can assign to a defender:

• Keep an assigned offensive player under his usual scoring average.

• Stop a great passer from recording his usual number of assists.

• Block out a great rebounder to reduce his offensive rebounds.

Team Goals. In addition to individual goals, also set team goals, which are important to motivate your team on defense. Here are some examples of team goals:

• Reduce the opponent’s number of dribble penetrations.

• Reduce the number of assists.

• Take away as many passes inside the lane as possible.

• Minimize fast-break opportunities.

Talk about the importance of defense at the first team meeting and then throughout the season. Talk both to the team and to individuals, perhaps particularly to your point guards, who are your right-hand men on the court. Also meet with team captains, who tend to have a positive influence on the team.

When you correct players in practice, be positive. Tell them what to do right, not what they’re doing wrong. Be sure to praise players when they perform techniques correctly.

Physical Skills

It’s true that playing defense is a state of mind. It’s also true that superb physical conditioning can enhance mental skills. When a player is on the defensive end of the court, he needs strength, stamina, and power to deal effectively with talented offensive players. This conditioning helps defensive players to sprint and recover in defensive transition, to pay the toll necessary in fighting through screens, to cope with all the bumping that occurs in the lane, to take charges and dive on the floor for loose balls, to rotate to help a teammate, and to block out a big, tough player. Without proper conditioning, the defender loses his mental toughness and is much easier to beat.

To attain superb physical conditioning, players must work on several areas, including

• flexibility, to improve performance and prevent injuries;

• core strength, to improve muscle balance, muscle movement, efficiency, and durability;

• agility, to be able to perform such demanding moves as changing direction and pace, repeated jumping, sprinting, cutting at various angles, and sliding while moving side to side and backward and forward; and

• speed, to be able to beat offensive players to spots and for recovering from rotations back or close up to their own men.

Preparing players for the tough demands of a long basketball season is the job of the strength and conditioning coach, an essential member of the coaching staff at any level of the game. This coach must work on individual programs appropriate to the physical and body characteristics of each player.

Technical Skills

Whenever you are building something, you need to start with a foundation, laying the first brick on the ground. On defense, the first brick is the coverage of the player on the ball, usually made by your point guard, the first line of your team’s defense.

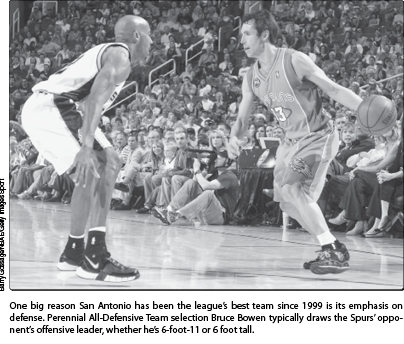

If you watch players like Chauncey Billups or Tony Parker, you see perfect examples of how to pressure the offensive player with the ball. The primary technical skills for pressuring individually on the ball are the defensive stance, step-and-slide moves, the close out, and stealing the ball.

Defensive Stance

Just as an offensive player must assume a correct basic triple-threat position as soon as he receives the ball, the defender must start in a proper defensive stance. Balance is key on all offensive moves with or without the ball, and the same is true on defense. Let’s examine the details.

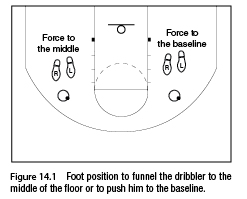

Foot Position. To establish a good base, place one foot forward and the other back, about shoulder-width apart. From here, you can quickly slide side to side or back and forth and can move either foot forward or back. Feet should be no more than shoulder-width apart to prevent loss of quickness. The lead foot is ahead of the back foot, and the toes of the back foot are aligned with the ball of the lead foot.

This foot positioning allows good balance, both laterally and back and forth. Which foot should be forward? It depends on the defensive philosophy of the coach. If a coach wants to funnel the dribbler to the middle of the floor, the defender keeps the foot nearest the sideline forward; if he wants to push the dribbler to the baseline, the defender keeps the foot farthest from the sideline forward (figure 14.1).

There’s often debate over where to place body weight. Many coaches say body weight should be on the balls of the feet; others disagree. In my view, players should do what’s most comfortable. Whether they put their weight on the balls of their feet or keep their feet planted, it’s all the same to me. All I ask is that their positioning doesn’t hinder their defensive sliding ability or quickness.

The key is how quickly players can move their feet. They must move with what I call a “step and slide” technique, which involves moving in a sequence of steps and slides—not bringing the feet together or crossing them. If they bring together or cross their feet, balance and quickness are affected, as is the ability to change direction quickly. They must lead with the foot closest to the direction of the dribbler. Here’s the pattern: right dribble, left foot lead step, right foot slide; left dribble, right foot lead step, left foot slide.

Leg Position. Bent knees make for quicker defenders. The knees should be bent as far as comfort allows. In most cases, we like our players to appear as if they’re trying to sit on a chair.

Trunk Position. The trunk should be slightly bent forward, but not too much. The primary bend should be at the knees, not the trunk. Too much bend at the trunk causes a loss of balance.

Hand Position. The role of the hands in the defensive stance is crucial. I teach defenders to raise the hand on the same side as the forward foot. The hand corresponding to the back foot (the back hand) is placed on the side to take away the passing lanes. This hand is constantly tracing the ball, trying to get a piece of it. The defender stays half a man away from the ball, with his nose on the ball.

Once the ball has been picked up and the offensive player can’t dribble anymore, the defender swings up the back hand and mirrors the ball, tracing the ball’s movements with hands crossed at the wrists, chesting up to the offensive player and aggressively pressuring him, trying to deflect the ball, taking away the passing lanes, and restricting the view of the offensive player by forcing him to turn his shoulders away from where he wants to pass.

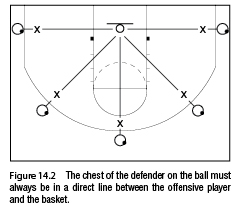

Chest Position. This is an important point. I tell players that when pressuring the opponent with the ball, they must always have their chest in front of them. When they’re in the middle of the court, on the wing, or in the deep corner, they should be in a direct line between the offensive player and the basket, with the chest always fronting the offensive player (figure 14.2).

When pressuring the ball, never assume a fencer or boxer stance. Athletes in these sports turn sideways, reducing exposure of the target to the opponent to avoid being hit. If a defender turns too much, he offers the ball handler a straight-line drive to the basket—a drive we want to avoid because it disrupts the entire defense.

Step-and-Slide Moves

As mentioned, when pressuring an offensive player dribbling upcourt, the defensive player moves with alternating steps and slides. The initial step-and-slide technique must take into account the speed and quickness of the offensive player as well as that of the defensive player. The quicker the defender is than the offensive player, the closer he can get up on the ball initially. The slower the defender, the farther away he needs to start.

Side to Side. This technique is used when the defender is quicker than the offensive player or the defender is trying to impede all progress of the ball, taking away all angles to the ball handler. It is the basic step-and-slide technique described earlier. Lead with the foot closest to the direction of the dribbler, keeping feet spread apart and moving them as quickly as possible. Try to anticipate which direction the ball handler is trying to take; then beat him to the spot and take it away, forcing the ball to change direction and repeating the process in the other direction.

Retreat Step Slide. This technique is used when the defender encounters a quick and clever ball handler or when the coach wants to force the offense to take time off the clock under pressure. The retreat step helps keep the ball in front of a slower defender. The defender takes his first step slide movements in retreat, giving ground and letting the ball come to him. This technique ensures that the ball remains in front of the defender and is not designed to force a change in direction of the ball.

Drop Step. Use the drop step in a step and slide to change directions quickly. As the defender is stepping with his left foot and sliding with his right foot, he cuts off the direction of the ball and forces it to change direction.

On the drop step, plant the outside foot and push off and change direction with the ball. Drop the inside foot and open up to avoid contact with the offensive player, retreating until you can get in front of the ball and gain control again.

Crossover Step. When executing the step-and-slide technique and losing ground to the offensive player, stay low and execute a crossover step to turn and then run to catch up with the ball. Sometimes you might need to take two or three running, or crossover, steps to catch up to the ball. Once back in front of the ball, revert to the step-and-slide technique.

Closing Out

One of the most important techniques in pressuring the ball is the closeout, which is used in simple help-and-recover situations, when rotating out of double teams on the post, when rotating out of traps in pick-and-rolls, after offensive rebounds, or when chasing loose balls. All these situations require a defender to close out on his man.

The closeout technique is about quickness, balance, and control. When closing out, you must recover quickly and get close enough to take away initial shots while also preventing drives to the basket. You must move quickly, maintain control, and stay low. You want to be able to challenge a three-point shot while also being prepared for a drive to the basket. As you get close to the offensive player, run in short, choppy steps so that you’re ready for a quick drive to the basket and can maintain balance when challenging a shot. If you’re standing upright or are off balance, you’ll tend to lunge at the shooter, who will fake and drive easily to the basket.

Stealing the Ball

Pressuring the ball means trying to create turnovers and force the offense into mistakes. It also means trying to steal the ball.

There’s no special technique to teach here because some players have the instincts to know when to go for the steal and some don’t. Ball steals are based on timing and gambling, but keep the gambling to a minimum. If you go for the steal and miss, the dribbler gets inside the defensive gut and puts the defense at a disadvantage. A missed steal can force defensive rotations and cause mismatches, such as guards defending and blocking out big men, and big men getting into foul trouble because they’re guarding smaller players—all serious problems for the defense.

Communication

Communication among defenders is extremely important. We created a defensive terminology that we use all the time, both in practice and games. Consistent terminology helps defenders move in a synchronized way; it alerts teammates that a screen is coming, where help is needed on the court, and how to play the pick-and-roll.

Here are some examples of the terminology we use:

• When we want to double team the ball handler on a pick-and-roll, we say “Blitz!”

• When we want to change defensive assignments as offensive players cross, we say “Switch!”

• When a defender gets over, under, or through a screen, we say “Over,” “Under,” or “Through!”

• In pick-and-roll situations, when the defensive player guarding the screener can’t stay attached to his man (usually in quick-hitting screens in transition) or when one offensive player sets a screen across, before that player goes and sets the screen, we say “Track!”

I want to add a quick note about tracking. The rule is that when a defender can’t stay attached to his man, he’ll take a defensive stance with chest facing the half-court, feet sliding sideline to sideline, trying to keep the ball in front of him until the original ball defender can recover. He doesn’t trap or show but just tries to contain the ball. Tracking is a passive technique. It prevents quick splits by guards coming off the pick-and-roll.

Tips on Special Individual Defense

Mainly in the NBA, but also at the high school or college levels, teams often face the problem of how to defend in special situations, such as against a great penetrator, a great shooter, or a player with a signature move. When trying to defend a player with special offensive skills, there’s always a trade-off. You need to determine how the player can hurt you most. If he’s dangerous in several areas, don’t expect to shut him down completely, but try to minimize his options so that he can’t beat you by himself.

Let’s looks at some guidelines for defending players with unusually strong offensive skills.

A Great Penetrator

When defending a great penetrator, you want to give yourself enough space without giving him too much space. There might be a very thin line between too much space and not quite enough, but you want to find that line. If the penetrator also has a good pull-up jump shot, you’ll want to play him a little closer but not so close that he can get by you. Most coaches choose to give up the perimeter shot rather than the penetration because penetration hurts the interior of the defense, creates foul trouble, and allows wide-open shots to be created when defenders help on the penetration.

A Great Shooter

You defend a great shooter by relentlessly dogging him to restrict his opportunities to touch the ball. You always want to be close enough to touch him when he catches the ball, before he has a chance to put up a shot.

Once the shooter catches the ball, don’t go for ball fakes; crowd him and force him to put the ball on the floor. Don’t let him get a good look at the basket. If he goes up for a shot, get an extended hand to the ball to challenge the shot. If you’re smaller than the shooter or if you have quick hands, try to strip the ball from his hands before he can get the ball into shooting position. Always force him to shoot with his weaker hand and from the direction he least prefers.

A Player With a Signature Move

Great players like Kobe Bryant, Tracy McGrady, Kevin Garnett, LeBron James, and Dwyane Wade have signature moves that make them dangerous on offense. When possible, watch film of such players to understand their tendencies. Study pregame scouting reports to develop a defensive strategy. A player might be weaker from one side than the other. You must learn his signature move and try to take it away from him as often as you can. If you take it away, he might find another way to score, but don’t get discouraged. Continue to focus on his most dangerous move. Team defense plays a big part in this. No single defender can guard these great players.

Drills for Pressuring the Ball

To pressure the ball, a player must have the desire and will to stop his offensive player, but he must also possess the proper defensive skills and techniques. These are only some of the many drills that can help to build a pressuring defense on the ball.

Zigzag

We use all four corners of the court for this drill. Big men play with big men, and the small with the small. You can run the drill on each half of the court or on the full court, depending on how many players are involved. The drill has four parts.

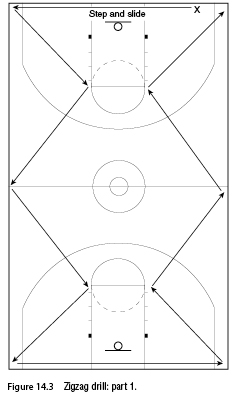

1. Players line up on the baseline at the right corner. Player 1 jumps onto the court facing the baseline, his back to the court and his hands together behind his back. He steps and slides, stepping with the left foot and sliding with the right foot, along the baseline from the right corner to the left corner. He then places his left foot at the intersection of the baseline with the sideline, drop-steps his right foot, changes direction, and then steps and slides with his right foot stepping and left foot sliding. When he reaches the free-throw line extended, he plants his right foot, drop-steps with his left foot, pushes with his right foot, and steps and slides with his left foot. He now steps and slides to the other free-throw line extension, drop-steps again, and then steps and slides until he reaches the intersection of the sideline and baseline. He then steps and slides along the entire baseline and repeats the same moves as he returns to the starting point on the other side of the court (figure 14.3). Once player 1 has reached the midpoint of the baseline, player 2 enters the court to begin the drill.

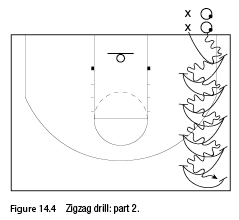

2. Players line up outside the baseline in one corner. This part of the drill starts with two players, one on offense, with the ball, and one on defense. The offensive player dribbles hard to the lane while the defensive player steps and slides to cut the dribbler off. The offensive player reverses the dribble and dribbles hard to the sideline, while the defensive player steps and slides to cut off the sideline. The offensive player continually dribbles to the lane and to the sideline while the defensive player continually slides and steps and cuts the dribbler off from the lane and from the baseline (figure 14.4).

This part of the drill ends at the half-court, where the two players exchange roles. They then return to the baseline in the same way as described.

3. The start is the same as the second part of the drill, but now the dribbler takes two hard dribbles and picks the ball up. The defensive player raises his hands, with wrists crossed, to jam and mirror the ball to prevent the pass.

The dribbler picks up the ball three or four times, and each time the defensive player jams the ball. The two players then exchange roles.

4. The offensive player now plays normally, trying to beat the defensive player to half-court, while the defensive player steps and slides and cuts the dribbler off as in a game situation. At the half-court line the two players exchange roles.

Five-Second Drill

Players are paired, with defenders inside the court and offensive players outside the court. We run this play on the half-court, using the two half-court sidelines, the baseline, and the half-court line (but you can use any line on the court).

The defender with the ball passes to the offensive player, who makes two hard dribbles, picks up the ball, and raises it over his head. The defender steps and slides to guard the two dribbles and, when the offensive player picks up the ball, jams the ball with the same technique as described in the previous drill (figure 14.5).

The ball handler dribbles back and forth from where he started the drill, and then the two exchange roles. This is a very short but intense drill; we emphasize the technique of jamming the dribbler.

One-on-One

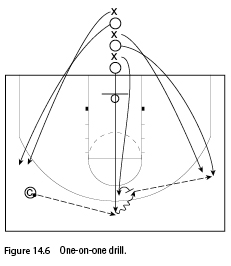

Six players line up on the baseline; the coach has the ball on the wing. At the call of the coach, the six players run onto the court. The first player is on offense, the second on defense, and so on; the three pairs set up on the two wings and in the middle of the court.

The coach passes the ball to one of the offensive players, who can go to the basket with only two dribbles or pass the ball to one of the teammates (figure 14.6). The drill ends only with a score or if the defense recovers the ball. If the offense makes more than two dribbles, the ball goes to the defense, and the defense goes on offense.

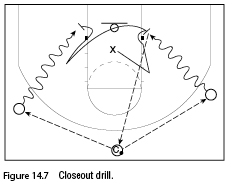

Closeout

A coach has the ball in the middle of the court. Two offensive players are set up at the wing positions, and a defender is in the middle of the three-second lane. The coach passes the ball to one of the offensive players, who drives to the baseline. The defender closes out, slides, and cuts off the path to the baseline, hitting the dribbler with his chest (not pushing him with his hands). At this time, the offensive player passes the ball back to the coach, who reverses the ball to the other offensive player, who drives to the baseline. The defender must recover, close out, and cut off the path to the baseline, while the offensive player can only drive, not shoot (figure 14.7).

Two-on-Two Help-and-Recover

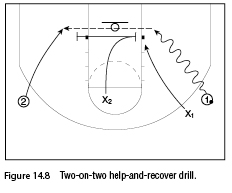

The ball is in the wing area or at the top of the lane in the hands of 1, while 2 is on the opposite wing. X1 covers 1; X2 helps and recovers on the baseline. 1 drives to the baseline or into the lane. As soon as 1 drives, 2 slides to the corner to receive the pass. X1 and X2 must communicate and not let the ball go to the baseline (figure 14.8).

Three-on-Three Help-and-Recover

The drill starts with offensive players 1, 2, and 3 on both wings and at the top of the key. The ball can start at any position on the court—top of the key or either wing (in the figure, the ball starts on the right wing). X1 guards 1 and forces him to drive to the baseline. X3 rotates off 3 and cuts off 1’s baseline drive. X2 rotates off 2 and picks up 3 on the baseline. X1 rotates off the baseline back to 2 at the top of the key (figure 14.9). The play is live and doesn’t end until the ball is secured by the defense or the offense scores a basket.

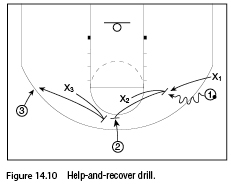

Out of the same set, the ball can be forced to the middle of the court to work on the help-and-recover and full rotation. The help-and-recover happens when the closest defensive player to the ball stunts to help take away middle penetration and recovers to his own offensive player. That is, X2 steps in to help stop the penetration by 1 and recovers to 2; X1 stays with 1; X3 is in a position to help X2 on 2’s penetration and then recovers to 3 (figure 14.10).

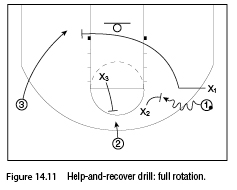

The full rotation occurs when the next closest defender rotates off his offensive man and traps the ball on penetration. The next defensive player then rotates to cover for that defensive player by picking up his open man (that is, 1 penetrates to the middle of the court, X2 traps the ball, X3 rotates to 2, and X1 rotates to 3) (figure 14.11).

These drills are designed to help with communication and quick reaction in help-and-recover and full-rotation situations. At the end of the drill, the offense goes off and the defense goes to offense. A new defense comes on the court. (Always send the next three players in on defense, not offense.) You can make the drill competitive by keeping score.

Final Points

As coach, you can decide to play any type of defense you choose—half-court or full-court man-to-man, zone, or matchup—based on the rules at your level of play and your philosophy of the game. But no matter what defense you play, if you want to be aggressive, the most important step is to pressure the offensive player with the ball. If the ball is easily passed around the perimeter, gets easily inside to the low-post area, or is quickly reversed, your defense won’t be at all effective. Pressuring the ball is the key to any type of defensive set and is by far the most important aspect of this phase of the game.