Epilogue

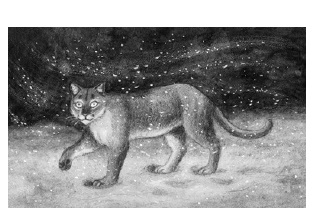

Cougars do exist in Waterton Lakes National Park and elsewhere within North America, though they are rarely seen. Collaring animals such as bears and cougars is one way scientists can follow an animal’s movements and determine the size of its range, and the collaring techniques described in the story are actually used by scientists studying cougars. Just a decade ago the collar had to fall off the animal before data could be gathered. Today improvements in GPS (Global Positioning Systems) and remote data gathering enable scientists to track a cougar in real time, seeing where it is going as it is moving.

Cougars are at the top of their food chain, so by studying them scientists are able to evaluate the overall health of an ecosystem. A rise in the cougar population means there is an abundance of prey animals, such as deer, elk and moose, as well as smaller prey like hares, grouse and even porcupines. But a rise in the cougar population also means that young cougars must travel farther in their search for unoccupied territory, sometimes bringing them into contact with human populations.

In 2005 it was estimated there were only 680 cougars in Alberta. In 2015 that number had risen to more than 2,000. By studying cougars, scientists hope to understand how humans, livestock and cougars can coexist.