TWELVE

THE B-29s STARTED their long flights to Tinian Island during the first week of June. My crew and I were among the last to leave the windswept desert of Wendover.

Dorothy had known for over a month that I was shipping out. There was no question she would return to Boston. Wendover had the feel of a ghost town. No one in their right mind would want to stay there, and in any event, there was no telling when I’d be back—a year, two . . . who knew? On June 19, our last morning together, we had breakfast, said our good-byes, kissed and hugged, and spoke of when we’d meet again. My crew and I lifted off for the last time from the hardscrabble place that had been our home for the past several months. I swung around toward our house, circling it at about 100 feet. There was Dorothy, standing alone in the dust bowl we called our front yard, waving. I dipped my wings to let her see me and then waved the wings in a final good-bye as I continued my turn. Banking the airplane up, I swung around back toward the west and on to Sacramento.

During the afternoon of June 21, we landed in Hawaii at the end of the first leg of our journey. After a brief layover that night, we flew on to Kwajalein, where we stayed the second night, and then on to the Marianas and the island of Tinian the next morning. There was an unconcealed excitement among the men. We were going to war.

One year earlier, as marines stormed ashore and eventually took Tinian, hundreds of Japanese soldiers went into hiding in the caves, jungles, and hills around this tiny island. They continued to radio reports of our activities to neighboring islands still held by Japanese forces. We were warned not to venture too far out after dark. Not long after our arrival, in spite of the tight security surrounding our group, Tokyo Rose welcomed the 509th to Tinian and encouraged us to go home to our loved ones before we were killed. In later broadcasts, she assured us that Japanese fighter planes and antiaircraft gunners would take special aim at the mark on the tails of our airplanes, our distinctive arrowhead inside a circle. Although none of us would admit it, her broadcasts were a little unsettling.

Approaching from the air, each of the islands of the Marianas is a green, lush oasis in a vast blue. Up until then, those islands had been only names I had read about or seen in the black-and-white starkness of movietone news clips, or in the more graphic uncensored military combat films. Saipan, Tinian, Guam. It was hard to square the beauty of the Marianas with the human suffering visited upon them so recently. With the exception of our foray into Cuba, this was my first trip ever outside the continental United States.

After getting clearance from the tower, I began my final approach from the west and landed on one of the four parallel 8,500-foot-long runways on North Field that ran east to west across the northern tip of Tinian. Literally overnight, navy construction battalions, the Seabees, had constructed these mammoth airstrips and ancillary facilities. These facilities constituted the largest airfield in the world at the time.

Servicemen overseas like to bring a feeling of home to their bases whenever they can. Some enterprising engineer—I suspect he was from New York City—found a way to bring New York to our new base. Tinian is shaped much like the island of Manhattan—elongated, north to south. The streets on Tinian were laid out and named after the streets in Manhattan. Broadway and Eighth Avenue ran the length of Tinian, with Wall Street, Forty-second Street, 110th, and so on, intersecting. The address for the 509th was the corner of 125th Street and Eighth Avenue, formerly occupied by the Seabees. We lived in “Upper Manhattan.” It pleased me to no end that someone had named the road that ringed North Field, Boston Post Road.

Before we arrived, Tinian had been occupied by the 313th Bombardment Wing of the XXI Bomber Command, flying incendiary missions over Japan and dropping mines by parachute into the waters of Japan’s harbors to stop the flow of ships supplying Japanese troops. Our group was to be nowhere near the 313th on the island, however. The 509th was totally isolated within its own compound, connected by taxiways to North Field. The compound was enclosed by a high fence with a main gate that was guarded around the clock by armed sentries. The perimeter of the fence was patrolled by heavily armed MPs. Inside the security perimeter were our living quarters and offices, a series of Quonset huts connected by a network of roads. Our working areas were the flight lines, located two miles from our living quarters. This area contained the only windowless, air-conditioned buildings in the Pacific, where the Alberta and Manhattan scientists and technicians and the First Ordnance personnel were laboring. Here the various components of the bombs would be assembled. The actual bombs’ casings and electrical circuits were also kept in this area, awaiting the internal workings that would breathe life into the weapons—uranium and plutonium firing mechanisms and cores. Anyone trying to gain access without proper clearance could be shot.

At North Field, our airplanes were under the same degree of security. No one was allowed near our aircraft or the specially dug concrete loading pits. Unauthorized personnel were also subject to being shot.

The accommodations within our compound were the best on the island—and possibly in the entire Pacific. The Seabees, who had built and lived in our quarters, had spared no amenities. Tibbets and I, for example, had private showers. Each day tubs constructed on top of the huts were filled with water by a tanker truck. I would step into a closet enclosure, pull a chain, and down cascaded water warmed by the sun. I would then soap up, pull the chain to rinse off, and I was done. Just like home.

As combat-hardened veterans, the Seabees were the first to go into forward areas, constructing vital airstrips and facilities, many times under enemy fire, as the marines pressed on from island to island. They were leaving for duty on Okinawa as we were arriving on Tinian, and we inherited their quarters. This started an undercurrent of ill will toward the 509th among other units on Tinian, which was intensified by our isolation and apparent special treatment.

After the bleak, dreary endlessness of Wendover, life on Tinian was lush. It was a tropical island, hot and humid. We swam in the warm, crystal-clear ocean during the day and at night sat under a star-encrusted sky.

We attended the 313th Wing ground school to learn the particular operations in this theater, such as weather patterns, air-sea rescue procedures, and flight patterns in and around airfields. We did not, however, fly missions within the command, and our aircraft could not be reassigned to non-509th crews, regardless of the need. Our maintenance operation and vast resources were not subject to the jurisdiction of the wing commander or the island commander. We were untouchable.

The other B-29 crews were flying into the teeth of the enemy every night, carrying maximum loads of bombs, often barely making it into the air to start a journey of thousands of miles round-trip. Many never got airborne. Their airplanes would perhaps lose an engine on takeoff and then crash and explode in the ocean if they were unable to dump their payloads quickly enough before impact. Loaded with thousands of pounds of weaponry, the B-29 could be unforgiving in those first few moments as it struggled to gain altitude. Crashed-out hulks of the unsuccessful were not an uncommon sight.

These brave men looked upon us as contributing nothing to the war effort. We had no mission they were aware of. From an objective point of view, I could sympathize with their disdain. We seemed destined to finish out the war training for an illusory mission.

We got the green light to commence practice missions over the neighboring islands of Rota and Guguan, which were still occupied by the Japanese. Our forces had bypassed those islands because they possessed no strategic value and, with their supply routes cut off, posed no danger to our forces in the Marianas. The missions would give our crews an introduction to theater operations without exposing them to enemy antiaircraft fire. The last thing we needed was to lose one of our specially trained crews while it was dropping practice bombs on an irrelevant target.

The airplanes on these missions would drop pumpkins, but unlike the Wendover pumpkins, these would be filled with Torpex, an enhanced explosive with an enormous destructive yield for a conventional bomb. We would release from 30,000 feet and the explosion would allow us to spot where it hit, whereupon the crew would maintain course until it took vertical photos of its own damage.

After a series of runs we were authorized to bomb Truk and Marcus, where the Japanese had such limited antiaircraft batteries to throw up at us that they would have little or no effect. This provided our first combat conditions, even though these runs were still recorded as “practice” missions by the air force.

On July 20 we were finally cleared to fly missions over Japan. The targets were Otso, Taira, Fukashima, Nagaoka, Toyama, and Tokyo. With the exception of Tibbets and a handful of the men he’d brought in at Wendover, most of the members of the 393rd would be flying their first combat missions. Tibbets, Beahan, Ferebee, and Van Pelt had flown missions in Europe. Captain Fred Bock and Lieutenant Colonel Classen had seen tours of duty in the South Pacific. It would be my first combat over enemy territory. At long last, we were in the war.

These missions over Japan would have the same profile as the real one, if it ever happened. Each airplane would carry a single pumpkin filled with Torpex, drop it on a target, and then take vertical photographs of the damage. Although inflicting damage on the enemy would be welcomed, it was a collateral objective. We were dress-rehearsing for the big day. The crews would be navigating long-range over water to a primary city in heavily defended enemy territory and dropping the weapon visually from 30,000 feet on a specific enemy target. The target might be a factory or a military base or a railroad yard. The goals were accuracy and assessment.

Unfortunately, these missions would also confirm that the fuses were still unpredictable. On at least two occasions, fuses detonated before the pumpkins reached the point where they were scheduled to explode. The airplanes were far enough away from the explosions at the time not to have taken any damage, but after all the tactics and maneuvers our crews had perfected, we were silently aware that for one piece of the puzzle, all we could do was hope that perfection would be achieved.

Each crew would be briefed on a secondary target and a tertiary target if the primary target could not be bombed because of weather or any other problem. If the secondary and tertiary targets were obscured, the pilot, on his own initiative, could drop on so-called targets of opportunity. The only prohibition in the theater was that under no circumstances were the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, where the emperor resided, and the ancient city of Kyoto, a religious and cultural center for the Japanese, to be bombed. We were not seeking to destroy a culture but to stop an aggressor. And as a practical matter, killing or injuring the emperor or destroying a center of cultural and religious importance might also give the regimented Japanese public another rallying point around which to mobilize in a final suicidal defense of the home islands. Also on the off-limits list were Hiroshima, Kokura, Nagasaki, and Niigata for reasons that were not explained to us by Colonel Tibbets.

The Torpex drops also had the effect of allowing the Japanese to get accustomed to seeing a single B-29, unescorted by fighter aircraft, drop a single bomb from 30,000 feet. Perhaps they would become comfortable with a tactic that inflicted so little damage and choose to concentrate defensive measures against other more destructive air assaults. Some of the men wondered aloud if this was the reason we had been training so hard and in such secrecy—to drop new, huge, powerful iron bombs, one at a time. Could the brass have overestimated the desired effect?

There were two further prohibitions. Colonel Tibbets and I were never to fly together over Japan, and Tibbets was prohibited from flying any of these combat missions. His capture by the Japanese could jeopardize the entire Manhattan Project. Within the 509th, he was the only one who knew practically everything.

Four days before we began our assault on the Japanese mainland, at Alamogordo, New Mexico, the first nuclear weapon had been successfully detonated. Events were now gaining momentum. On July 26, we heard over Armed Services Radio that the terms of the Postdam Declaration called for the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces.

Japan stalled. The killing went on. Every day hundreds of Americans continued to be killed and wounded in battles throughout the Pacific, in Southeast Asia, and in barbarous prisoner of war camps. The Japanese treatment of our POWs defied humanity. When their army decided to force-march thousands of prisoners from Bataan in the Philippines sixty miles north to Camp O’Donnell—many of the prisoners wounded and some barely alive—they murdered over seven thousand American and other Allied prisoners on the march alone. The men were shot, stabbed, decapitated, or otherwise physically destroyed during that agonizing journey. Their captors withheld food, water, and medical treatment. Those prisoners who were still alive at the end of the march, along with other POWs, were placed in camps that were repositories of unmitigated horrors, camps such as the one at Palawan, where 150 emaciated prisoners were forced into an air raid shelter. The guards poured gasoline into the shelter and then set it ablaze. Those who tried to stagger out were machine-gunned, clubbed, or bayoneted to death.

Years later we could learn of the Nazi-esque medical experiments conducted on prisoners.

Of the 140,000 Americans held by the Japanese, 34 percent—47,000—would die in captivity. The survivors would be remnants of the men they had been.

In words and deeds, Japan also made known its intention to execute every Allied prisoner of war at the start of any planned invasion of the mainland. Everywhere they were held, prisoners were ordered to dig slit trenches to serve as mass graves for the executions. On Formosa, the prison camp commander was directed, in the event of an invasion, to kill all prisoners. On Java, 300,000 Allied prisoners—American, Dutch, British, and Australian; civilian and military—were in jeopardy. At Davao, in the Philippines, machine gun emplacements were constructed to face inward and stores of gasoline were being stockpiled to burn bodies. Earlier, at places like Tarawa, Ballale, and Wake Islands, the Japanese shot or beheaded all of their POWs in anticipation of American invasions.

Thus, the United States had good reasons to take the Japanese threat seriously.

In the context of this reality, on June 18, in a meeting at the White House, Admiral William Leahy advised the president that, based on our experience at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, in the first thirty days of an invasion we could realistically expect casualties in the range of 230,000 to 270,000. For a 120-day campaign to invade and occupy only the island of Kyushu, casualties could reach 395,000.

But President Truman possessed the means to perhaps bring the war to a quick and decisive end.

In the following week the list of targets grew. On July 24 I flew a strike against the marshaling yards at Kobe.

The 509th almost made history of a different kind during these missions, and the legend of Claude Eatherly grew in ways he did not intend. On Eatherly’s first flight, his primary and secondary targets were socked in by cloud cover. He had his navigator chart a course to Tokyo. His intended target: the Imperial Palace. This action was in direct violation of American policy, not to mention direct orders from the commanding general of the theater, General LeMay, and Colonel Tibbets. It was a court-martial offense. Aiming at his target, Claude found that Tokyo was also obscured by cloud cover, making a visual drop impossible. Undeterred, he dropped the bomb by radar. Fortunately, the Torpex-filled pumpkin fell wide of its intended target and no damage was done to the emperor or the palace. The bomb did obliterate a railroad station, though. History had not been altered by the act of a single loose cannon.

As events set in motion years earlier approached reality, Tinian, in a sense, became the center of the universe. Two billion dollars of our national treasure; years of tireless work by thousands of scientists, technicians, and mechanics; and the efforts of the best minds of the century were about to be handed over to us. On the morning President Truman announced the terms of the Postdam Declaration, the cruiser Indianapolis arrived at Tinian. Its cargo contained the firing mechanism for a bomb, and a machined uranium “bullet” resting in a lead container to prevent radioactive leakage. This cargo was stored in the assembly building to await delivery of the uranium core at which the “bullet” would be fired. Also awaiting delivery was the plutonium core for the second bomb, the real pumpkin. These additional components were en route from Hamilton Air Force Base in California aboard three B-29s, each carrying separate radioactive packages.

A few days after we watched the Indianapolis depart from Tinian en route to Leyte, in the Philippines, a Japanese submarine sank her. Although a radio distress message had been transmitted before she slipped to the bottom of the ocean, rescue did not come to the men who baked in the relentless tropic sun, floating helplessly in the tranquil, shark-infested waters, for four days. In the fog of war, by some perverse oversight, military authorities at Leyte didn’t notice that the Indianapolis was missing. A lone aircraft chancing over the area spotted the remaining survivors. Before surface ships arrived, over eight hundred men had died, many devoured by sharks. It was the last American capital ship sunk in World War II.

Charles W. Sweeney as an Air Cadet, 1940

Charles W. Sweeney as an Air Cadet, 1940

(l. to r.) Admiral Purnell, General Farrell, Colonel Tibbets, and Commander Parsons

(l. to r.) Admiral Purnell, General Farrell, Colonel Tibbets, and Commander Parsons

The Hiroshima Mission Briefing. Colonel Tibbets is seated third from the left, holding his pipe. Major Sweeney is two rows back over Tibbets’s right shoulder.

The Hiroshima Mission Briefing. Colonel Tibbets is seated third from the left, holding his pipe. Major Sweeney is two rows back over Tibbets’s right shoulder.

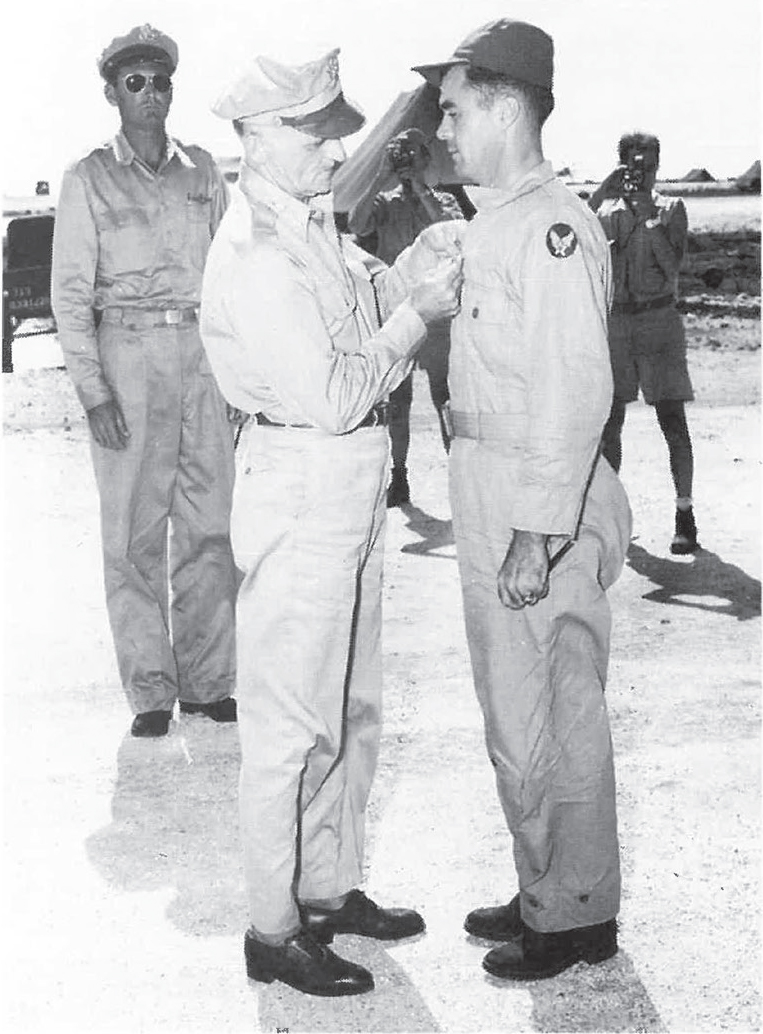

Tinian. General Spaatz awarding Colonel Tibbets the Distinguished Service Cross, August 6, 1945, after the Enola Gay landed. At the time, the DSC was the second highest award for valor.

Tinian. General Spaatz awarding Colonel Tibbets the Distinguished Service Cross, August 6, 1945, after the Enola Gay landed. At the time, the DSC was the second highest award for valor.

The crew of the Bock’s Car immediately after landing on Tinian, after returning from Okinawa on August 9, 1945. (l. to r., bottom row) Kuharek, Spitzer, Gallagher, Buckley, Dehart; (top row) Sweeney, Albury, Olivi, Beahan, Van Pelt, Beser

The crew of the Bock’s Car immediately after landing on Tinian, after returning from Okinawa on August 9, 1945. (l. to r., bottom row) Kuharek, Spitzer, Gallagher, Buckley, Dehart; (top row) Sweeney, Albury, Olivi, Beahan, Van Pelt, Beser

The Bock’s Car after the Nagasaki mission

The Bock’s Car after the Nagasaki mission

The atomic explosion over Nagasaki

The atomic explosion over Nagasaki

The destruction at Nagasaki, September 1945

The destruction at Nagasaki, September 1945

General Davies awarding Major Sweeney the Air Medal after the Nagasaki mission. Later, he would be awarded the Silver Star for bravery by Lieutenant General Nathan Twining.

General Davies awarding Major Sweeney the Air Medal after the Nagasaki mission. Later, he would be awarded the Silver Star for bravery by Lieutenant General Nathan Twining.

The Bock’s Car on display at the Air Force Museum, Dayton, Ohio

The Bock’s Car on display at the Air Force Museum, Dayton, Ohio

Major General Charles W. Sweeney today

Major General Charles W. Sweeney today