In future time, through all coming generations, let the king, who may be in the land, observe the words of righteousness which I have written on my monument; let him not alter the law of the land which I have given, the edicts which I have enacted; my monument let him not mar. If such a ruler have wisdom, and be able to keep his land in order, he shall observe the words which I have written in this inscription; the rule, statute, and law of the land which I have given; the decisions which I have made will this inscription show him; let him rule his subjects accordingly, speak justice to them, give right decisions, root out the miscreants and criminals from this land, and grant prosperity to his subjects.

—The Code of Hammurabi, circa 1750 B.C.

FOR THERE to be a solution to a crime, forensic or otherwise, there must first be actions that are defined as criminal. The definition of crime varies from time to time, place to place, and context to context. Killing another human being is murder—except when it isn’t, as in war or when mandated by the state as an execution. Incest is a crime—unless you are the pharaoh of Egypt and are expected to marry your sister. For many centuries, harboring a runaway slave was a crime; today, throughout the world, slavery itself is illegal.

For most of history, a crime has been whatever the local ruler declared it to be. Local officials twisted the laws to suit themselves since few people knew just what was prohibited or just what punishments there were. Indeed the nobles of ancient Rome held on to their power partly by keeping others in ignorance of the laws they nevertheless enforced with great severity against the plebeian classes. After a few hundred years of this, even the nobles decided that the privilege was not worth continuing. An ambassador was sent to Athens to study Greek law and to draw up a definitive set of laws for Rome; and in 449 B.C. the Law of the Twelve Tables was published on twelve bronze tablets and set up in the Forum.

More than a thousand years earlier, Hammurabi, the king of Babylon from about 1796 to 1750 B.C. decided that everyone had a right to know what the laws were. This may have been a ploy to prevent his own nobles from making up the laws as they saw fit. In any event, he inscribed his body of laws, known today as the Code of Hammurabi, on seven-foot-high stone slabs that were then erected at various places around his kingdom. All of them have disappeared over the centuries, except for one that was found in 1901 by the Egyptologist Gustav Jéquier during an expedition to ancient Elam, a town in Khuzestan, a province of present-day Iran. On it Hammurabi begins by stating his authority:

. . . Anu the Sublime, King of the Anunaki, and Bel, the lord of Heaven and earth . . . assigned to Marduk, the overruling son of Ea, God . . . dominion over earthly man, and made him great among the Igigi, they . . . called by name me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince, who feared God, to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak; so that I should rule over the black-headed people like Shamash, and enlighten the land, to further the well-being of mankind. . . .

Then he got down to business with 282 specific injunctions, some of interest to us:

If any one ensnare another, putting a ban upon him, but he cannot prove it, then he that ensnared him shall be put to death [an apparent forerunner of “thou shall not bear false witness”].

If any one bring an accusation against a man, and the accused go to the river and leap into the river, if he sink in the river his accuser shall take possession of his house. But if the river prove that the accused is not guilty, and he escape unhurt, then he who had brought the accusation shall be put to death, while he who leaped into the river shall take possession of the house that had belonged to his accuser [crime-solving by magic].

If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death. . . .

If any one break a hole into a house [break in to steal], he shall be put to death before that hole and be buried. . . .

If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out [the now familiar “eye for an eye”].

If he break another man’s bone, his bone shall be broken.

If he put out the eye of a freed man, or break the bone of a freed man, he shall pay one gold mina.

If he put out the eye of a man’s slave, or break the bone of a man’s slave, he shall pay one-half of its value.

If any one strike the body of a man higher in rank than he, he shall receive sixty blows with an ox-whip in public.

If a free-born man strike the body of another free-born man of equal rank, he shall pay one gold mina.

If a freed man strike the body of another freed man, he shall pay ten shekels in money.

If the slave of a freed man strike the body of a freed man, his ear shall be cut off. . . .

If a builder build a house for some one, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built fall in and kill its owner, then that builder shall be put to death.

Sometime during the third century B.C., Hier on II, the tyrant of Syracuse, gave a quantity of gold to one of the city’s goldsmiths. He was asked to fashion a gold laurel wreath as a crown for the winning athlete at an impending festival. For a reason long lost to history, Hieron came to suspect the goldsmith of secretly replacing some of the gold with an equal weight of silver—not a good trick to play on a tyrant. But was it true? Hieron asked the city’s leading citizen, the polymath Archimedes, to devise a method to detect this possible debasing, preferably one that wouldn’t involve the destruction of the wreath.

As told two centuries later by the Roman architect and historian Vitruvius, Archimedes saw the answer to his problem as he sank into his bathtub and noticed the water displaced by his body spilling over the edge. With a great cry of “Eureka!” he leaped from the bath and ran naked through the city streets.

Watching his body push the water from the tub, Archimedes had realized that an ounce of gold, being denser than an ounce of silver, would displace less water because it had less volume. If you picture an ounce of copper—eleven pennies—as opposed to an ounce of balsa wood—about the size of four decks of cards—you have an exaggerated image of the phenomenon. All Archimedes had to do was drop the crown in an amphora filled to the brim with water and then do the same with a lump of gold that weighed the same. If more water flowed out with the crown than the gold, it proved that something had been added to the mix.

Or he might place the crown on one side of a balance scale and enough gold onto the other pan to bring the scale into balance. The scale would then be immersed in water. If the crown were not pure gold, it would displace more water—the difference in buoyancy would cause the lump of gold to sink and the crown to rise. Whichever method Archimedes used, Vitruvius records that the crown was shown to be debased, and the goldsmith was beheaded. Archimedes might be the first European to use science to solve a crime.

Some fifteen hundred years later, in the fourteenth century A.D., we find the first recorded use of expert testimony in criminal trials in Europe. Among these earliest expert witnesses were “masters of grammar” who could read and interpret the medieval church Latin in which the laws were written and so determine the proper form for such swearing.

In a 1554 trial, Buckley v. Rice, the judge noted that “If matters arise in our law which concern other sciences or faculties, we commonly apply for the aid of that science or faculty which it concerns, which is an honorable and commendable thing in our law, for thereby it appears we do not despise all other sciences but our own, but we approve of them, and encourage them as things worthy of commendation.”

Back then, the word “science,” from scientia, the Latin word for knowledge, connoted “what there is to know,” rather than the formal study of a particular field of knowledge. But the beginnings of forensics can be found in this four-centuries-old ruling.

Among criminal matters, none is more serious than capital cases; in capital cases nothing is given more weight than the initially collected facts; as to these initially collected facts nothing is more crucial than the holding of inquests. In them is the power to grant life or to take it away, to redress grievances or to further iniquity.

—Sung Tz’u, The Washing Away of Wrongs, 1247

As seems to be true of much of human knowledge, the roots of scientific forensic investigation lie in ancient China. When Portuguese traders arrived in Canton in 1517 they were impressed by how carefully and thoroughly Chinese judges examined the facts of their criminal cases before reaching their verdicts, particularly when compared to European practice of the time.

Robert van Gulik (1910–1967), a Dutch citizen who grew up in Indochina and who spoke Mandarin Chinese, became interested in medieval Chinese detective stories when he was a member of the Dutch diplomatic mission in Peking. Once a popular genre, they were almost unknown in the China of the 1940s. Van Gulik began translating one of the classics, Dee Goong An (The Criminal Cases of Judge Dee), into English in 1947 and completed it in 1949 while stationed in Tokyo. Set in T’ang dynasty China, the tale is based on the career of Ti Jen-chieh, an actual magistrate who lived from 630 to 700 A.D. and who was an astute solver of complex crimes. The original stories about Judge Dee and other famous magistrates on which van Gulik based his tales were composed in the seventeenth century. Based on thousand-year-old criminal cases, the tales show that the function of the criminal investigator was well understood by the Chinese long before it developed in the West. Judge Dee used a staff of investigators when he didn’t go forth in disguise himself.

The procedures of his time called for the examination of witnesses, suspects, and physical evidence. In order to determine the cause of death in possible murder cases, bodies were examined by specially designated coroners. Since a case could not be closed until a culprit confessed, a magistrate who was convinced of a suspect’s guilt might judiciously apply torture to induce a confession. If the magistrate was mistaken and tortured the wrong man, he himself could be subjected to whatever torture he had inflicted on the suspect—a system that created a harsh but careful judiciary. In these seventeenth-century stories the magistrates also put great faith in the intercessions of ghosts and spirits to guide them to the truth.

Chinese forensic techniques and procedures were well established two thousand years before the original Dee Goong An was written. Archaeologists at a dig of a Ch’in dynasty tomb in Hubei Province in 1975 discovered a bundle of bamboo strips on which were inscribed a text that dates to the period known as the Warring States (475–221 B.C.). Compiled by then-chancellor Lü Puwei, the text, known as The Spring and Autumn of Master Lü, is a manual of forensic procedures. One section of it discusses how to examine a crime scene; one how to relate evidence found at the scene with the findings of the lingshi (the coroner); another how best to examine a corpse for broken bones and other trauma; and another how to determine the time of death from the condition of the body. In cases of death by hanging, the coroner recorded the sort of rope used, the structure from which it was hung, the position and location of the victim, and the state of the body. The victim’s friends and relatives were questioned about the victim’s affairs and asked to suggest the names of anyone who might have had a motive for the crime.

Establishing the exact cause of death, or the amount and type of trauma suffered by the victim if he lived, was vital—the type and severity of punishment depended on the degree of harm inflicted. During the Sung dynasty (960–1279 A.D.), punishments authorized by the state included beatings with the “light rod,” beatings with the “heavy rod,” imprisonment, and execution. The Sung Code of 962 A.D. established the penalty for a severe assault at forty blows of the light rod. But:

If there are wounds or if weapons other than fists are used, the penalty is sixty blows of the heavy rod. If the wounds cause the loss of a square inch of hair or more, the penalty is eighty blows. If blood is drawn from the ear or eye, or there is the spitting of blood, one hundred blows.

A book called Yi Yu Ji, which apparently translates to A Book of Criminal Cases, dating to the Wu dynasty (264–277 A.D.), relates that the coroner Zhang Ju investigated the case of a man whose body had been burned in a fire. His wife was suspected of killing him and of then setting the fire to cover her crime. She denied it, of course, saying that the fire had been a horrible accident.

Zhang Ju made a fire like the one that had killed (or not killed) the man. In it he burned two pigs, one alive and the other dead. When he examined the bodies of the pigs afterward, he found that the live pig had ashes in its mouth while the already dead pig did not. The victim had no ashes in his mouth and so, Zhang Ju concluded, he had already been dead when the fire was set. The woman confessed to murdering her husband.

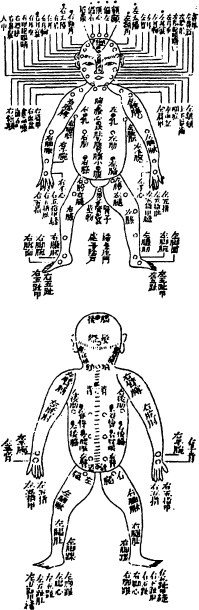

In 995 A.D., Emperor T’ai Tsung decreed that in all cases of suspected homicide or of death involving bodily injury, a coroner be appointed and an imperial inquest held. The coroner was required to inspect the crime scene, conduct a postmortem on the body, and report his findings to the imperial authorities. In his report he was required to include a front-and-back diagram of the body with wounds or other markings indicated. This procedure formalized and standardized investigations into suspicious deaths.

Under the Sung dynasty in China, coroners who inspected a crime scene were required to submit a front-and-back diagram of the body with wounds or other markings indicated.

Toward the end of the Sung dynasty, Sung Tz’u, a jurist who as a junior official had become known for successfully suppressing bandit gangs in several provinces, rose to the high office of judicial intendant. He wrote a book of criminal forensic procedures entitled Hsi yüan chi lu (The Washing Away of Wrongs). Published in 1247, it remained in print and in use for the next 650 years.

It includes the following advice:

A coroner must be serious, conscientious, and responsible.

He must personally examine each dead body or the wounds of an injured person. The particulars of each case must be recorded in the doctor’s own handwriting.

A coroner must not avoid performing an autopsy because he detests the stench of corpses. A coroner must refrain from sitting comfortably behind a curtain of incense that masks the stench, must not let his subordinates do the autopsy unsupervised or allow a petty official to write his autopsy report, leaving all the inaccuracies unchecked and uncorrected.

Much in the writings of Sung Tz’u has a modern feel to it. In the case of a serious assault and battery, The Washing Away of Wrongs ruled that if the victim were seriously injured, a recovery period was to be set. If the victim died within this period, he was deemed to have died of his wounds, and the accused would then be tried for murder. If he lived beyond the recovery period or died of a cause that was obviously unconnected to the crime, only assault was charged. Then, ironically, the victim was placed in the care of the accused, the person with the strongest possible motive for wishing him a complete recovery.

Sung Tz’u did not have the highest opinion of the motives or behavior of his fellow men, nor even of his fellow bureaucrats. He suggested, for instance, that if the relatives of the victim did not wish to have an inquest, it was perhaps because they had been bought off by the accused. He believed that an attendant at an inquest who accepted a gift from anyone should be punished. He stressed that the officials conducting the inquest eschew personal relationships with anyone involved and avoid staying at the houses of the relatives of either the victim or the accused.

In some of Sung Tz’u’s advice you can hear the exasperated sigh of the practitioner trying to drum some sense into the heads of his subordinates: “In writing up inquests, do not write ‘The skin was broken. Then blood flowed out.’ In general when the skin is broken, blood flows out.”

His descriptions of what to look for in suspicious deaths are precise and detailed:

When people have committed suicide by hanging, the eyes will be closed, the lips and mouth black, and the mouth open with the teeth showing. If hanged above the Adam’s apple, the mouth will be closed, the teeth firmly set, and the tongue pressed against the teeth but not protruding. [This] can easily be distinguished from cases where the victim was strangled by someone else . . . with the death passed off as suicide. Where the victim has really killed himself by hanging . . . the flesh where the rope crosses over behind the ears will be deep purple in color. . . . If another man strangled the victim and tried to pass it off as suicide, the mouth and eyes will be open, the hands apart, and the hair in disorder . . . and the tongue will neither protrude nor will it be pressed against the teeth.

The appearance of the body after being beaten with various implements—fists, staves, whips, axes, bricks, and a few others—is described. Detailed descriptions suggest what to look for in cases of drowning. Sung Tz’u differentiates between accidents, suicides, and murders. He describes the effects of various poisons. If the victim seems to have been in good health and there is no obvious cause of death, Sung Tz’u suggests that the official look for evidence of bamboo slivers inserted in the nose, ears, or under the fingernails, or for other objects forced into the mouth, rectum, or vagina. A careful search is to be made of the scalp to make sure that a nail hasn’t been driven through the skull and into the brain.

Sung Tz’u records the case of a particularly brutal murder in which a peasant was hacked to death with a rice-cutting sickle, a weapon that suggested an assault by a fellow peasant. The magistrate gathered the peasantry in the village square, where he inspected their sickles. There was no sign of blood on any of them. So he had them place their sickles on the ground. After a while the blowflies—shiny green flies with small spots of orange on their thoraxes—began to fly in random patterns around the sickles. These flight paths became increasingly less random, until shortly, most of the flies landed on one particular sickle. As carrion-lovers, the flies were attracted to bits of flesh and blood too small for the human eye to detect. The guilty peasant was led away, and the first recorded case of forensic entomology entered the record book.

The Washing Away of Wrongs remained the high point of forensic investigative techniques until modern scientific methods superseded classical Chinese empiricism. Yet the ethical standards demanded by Sung Tz’u are no less important today. Perhaps his words should be engraved over the entrance to every forensic science lab: A coroner must be serious, conscientious, and responsible.