If nature had only one fixed standard for the proportions of the various parts, then the faces of all men would resemble each other to such a degree that it would be impossible to distinguish one from another; but she has varied the five parts of the face in such a way that although she has made an almost universal standard as to their size, she has not observed it in the various conditions to such a degree as to prevent one from being clearly distinguished from another.

—Leonardo da Vinci

LET’S LOOK AT some of the problems raised by the seemingly simple problem of telling one person from another. In The Art of Cookery, an eighteenth-century cookbook by Hannah Glasse, the recipe for her allegedly delicious Jugged Hare begins, “Take your hare when it is cased,” meaning “First catch your hare.” The same problem exists with felons: they cannot be jugged until they are caught, and they cannot be caught until they are identified.

From the Middle Ages to modern times, felons who were not summarily executed (and there were hundreds of crimes for which the penalty was death) were branded. The purpose of branding was for identification—to warn good citizens to beware the offender—rather than for punishment. It was thought to be insufficiently painful in an era when the rack, the thumbscrew, and the whip were in common use. In France, from the fourteenth century on, the fleur de lis was branded on the shoulder of a released convict. In eighteenth-century Britain, thieves who escaped hanging were branded on the cheek. In tsarist Russia, prisoners sent to Siberia were branded on both cheeks and the forehead. The practice did not die out around the world until the early twentieth century. It endured in China until 1905.

In various parts of the world, another form of identification by disfigurement was in use until quite recently—mutilation, usually ear or nose cropping, and castration. For many centuries China practiced amputation of the nose or feet. The practice of cutting off a thief’s hand, still the law in Saudi Arabia and other Arab states, serves the triple function of identification, punishment, and deterrence.

Branding and mutilation were generic solutions, however. They were not very effective in identifying specific individuals. One would know that a person sporting a brand, a neatly removed nose, or a V-shaped cut in his left earlobe was a felon, but not know just which felon he was. A positive means of identifying a specific criminal was needed, and it would be many centuries before it was found. In the Roman Empire, written descriptions of missing criminals and runaway slaves were distributed. These focused on many of the same details found in the portrait parlé, a method developed in the nineteenth century by Alphonse Bertillon and still used by some police forces today. But these were no more accurate than the powers of observation and description of the writer.

Eugène Vidocq, the reformed felon who became head of the Paris police in the 1820s, realized the importance of personal identification. In his memoir he wrote:

I was no sooner the principal agent of the police of safety, than, most jealous of the proper fulfillment of the duty confided to me, I devoted myself seriously to acquire the necessary information. It seemed to me an excellent method to class, as accurately as possible, the descriptions of all the individuals at whom the finger of justice was pointed. I could thereby more readily recognize them if they should escape, and at the expiration of the sentence it became more easy for me to have that surveillance over them that was required of me. I then solicited from M. Henry authority to go to Bicetre with my auxiliaries, that I might examine, during the operation of fettering, both the convicts of Paris and those from the provinces, who generally assemble on the same chain.

With the growth of cities in the nineteenth century and the establishment of professional police forces came attempts to systematize the identification process. As penitentiaries became the preferred places of rehabilitation, the idea emerged that repeat offenders were insufficiently penitent and should receive harsher sentences. Professional criminals facing these harsher sentences would then naturally go to extreme lengths not to be identified. Policemen, particularly detectives, were encouraged to attend weekly criminal parades in which all the suspects in custody were lined up. They would then stare at the faces of those passing through the system so that they might recognize them when they encountered them again. Visiting policemen from other jurisdictions were also expected to attend these local lineups so that they could memorize the features of local criminals and spot any felons wanted on outstanding warrants in their own cities.

It was the custom in New York City for detectives attending the lineups to wear masks so that the criminals could not return the compliment by recognizing them.

On occasion these efforts to identify wanted criminals and repeat offenders had unanticipated results. In July 1844 the prefect of the Paris police offered a reward of twenty francs for the identification of “recidivists,” as they were called. Often a felon who was certain that he would be recognized struck a deal with a friendly policeman who would then turn him in and split the reward.

But personal identification for police purposes has serious flaws. Many freshman psychology courses demonstrate the dangers of eyewitness testimony by having someone run unexpectedly into a classroom, fire a revolver, then run out, or perform some other attention-grabbing stunt. The professor then asks the students to describe the actions and the actor. Seldom does anyone get all, or even most, of the salient facts correct.

It is also true that people may not notice something that is right in front of them. On the internet you can find a wonderful four-minute clip of a basketball-tossing game. As an exercise in observation, you are asked to count the number of times the ball is passed between the players wearing white shirts. After coming up with the number, you are asked if you noticed anything else. So you play the clip again, this time on the alert for something even slightly strange. And this time you see what initially escaped your view—a woman (the website explains) in a gorilla suit entering from the right, walking between the players, thumping her chest at the camera, and exiting on the left.

Not only in the classroom is eyewitness testimony problematic. In 1803 a New York City carpenter named Thomas Hoag, happily married and the father of a young daughter, suddenly disappeared. Two years later his sister-in-law heard his distinctive lisping voice behind her on the street. Turning, she saw that the man behind her was indeed Hoag. She pointed him out to the authorities, who then arrested him for deserting his family. At his trial, eight people, including his landlord, his employer, and a close friend, identified him. He had a familiar scar on his forehead and a recognizable wen on the back of his neck.

But the defendant insisted he was in fact one Joseph Parker. To prove it, he brought in eight witnesses of his own, including a wife of eight years. The judge could not decide.

Hoag’s friend, with whom he had once exercised daily, remembered that Hoag had a large scar on the bottom of his foot. The defendant was asked to remove his boots, which he gladly did. There was no scar, and so Parker went home to his wife. Hoag was never found.

In Great Britain in 1877 there was a more serious case of mistaken identity. A man calling himself “Lord Willoughby” went to prison for defrauding persons whom the authorities referred to as “women of loose character.” Since the man was clearly not entitled to the name he claimed, the prison records settled on the name “John Smith” as a suitable identifier.

In 1894, less than a year after his release from prison, a cluster of women, “mostly of loose character,” complained to the police that they had been defrauded by a man who called himself “Lord Wilton,” or, on occasion, “Lord Winton de Willoughby.” Their descriptions of the man varied, but the bad checks the women had received all seemed to have been written in the same hand. About a year later, in December 1895, one of the ladies, Ottilie Maissonier, passed a Norwegian mining engineer named Adolf Beck on Victoria Street in London. She recognized Beck as Lord Winton de Willoughby and reported him to a policeman.

Beck protested his innocence, but the bobby took him back to the police station, where several other similarly defrauded women came to look at him. They too identified Beck as the bogus lord. A retired police constable who had dealt with the earlier “John Smith” was called in to look at Beck, and he also swore that Beck and Smith were one and the same man. His opinion was confirmed by a second officer.

Beck was convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison, a harsher sentence than he would otherwise have received had he not been listed in the criminal records as a repeat offender. In 1896, Beck’s lawyer managed to have the case reexamined on the grounds that the prison’s own records showed that John Smith had been circumcised, whereas Beck had not. The Home Office decided not to grant him a new trial but did order his previous conviction expunged from the prison record.

After he had served his term and had been a free man for almost three years, the unfortunate Beck was arrested once again on new complaints that read a lot like the old ones. This time he was convicted and sentenced as a repeat offender. But just as he was about to be sent away to prison, a man calling himself Thomas was charged with offenses much like those for which Beck had just been convicted. When confronted with Thomas, the women who had identified Beck realized that they had made a mistake.

The police, now suspecting the truth, brought in witnesses to both earlier crimes. Thomas was identified as the real “Smith” and as the man who had committed all the crimes of which Beck had been convicted. Beck was at once granted a “free pardon” and awarded £5,000 compensation.

Eyewitness identification is not helped by the passage of time. In 1981, John Demjanjuk, a sixty-two-year-old Ukrainian who had emigrated to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1952 and worked as a steelworker, lost his United States citizenship for allegedly entering the country under false pretenses. Then, in 1986, he was extradited to Israel to stand trial for major war crimes. He was accused by the Israelis of being “Ivan the Terrible,” a guard at the Treblinka death camp who had supervised the gas chamber and was responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Jews. In 1988, after the emotional testimony of Treblinka survivors who identified Demjanjuk as the monstrous guard, and despite his vehement denials, Demjanjuk was convicted and sentenced to death—a punishment that in Israel is reserved for those who commit crimes against humanity.

In 1993 the Israeli Supreme Court reversed the conviction. New evidence from Soviet archives showed that while Demjanjuk was probably a guard at Sobibor, another death camp in Poland (a charge he also vehemently denies), he was never in fact at Treblinka and was not Ivan the Terrible. The survivors’ identifications of Demjanjuk as the guard they had seen under stressful conditions forty years earlier, though made in good faith, were mistaken. Demjanjuk may indeed have been guilty of war crimes, but not of those charged against him. In 2009 he was deported to Germany, where officials are considering trying him for yet other war crimes.

An infrequent but interesting and complex problem of identity concerns who a person is not rather than who he is. The most famous case of this kind during the last century was that of the missing Grand Duchess Anastasia of Russia and of the several women who claimed to be her.

Tsar Nicholas II, the last of the Romanov dynasty, was murdered along with his entire family on July 17, 1918, by the new Bolshevik government. Their bodies were burned and buried in a pit, the location of which was kept secret. But a persistent rumor had it that Anastasia, the youngest of the tsar’s children, had escaped the massacre and was living under an assumed name in a foreign country.

Of the several claimants to her identity, the most convincing was a girl who jumped off a bridge in Berlin on February 17, 1920, one year and seven months after the mass execution. She claimed to have lost her memory, and she subsequently spent two years in a mental hospital where all the while people remarked on how closely she resembled the beautiful missing Anastasia. For want of a better name she called herself Anna Anderson. She claimed to have vague memories of another life, a grand and wonderful life cut short by tragedy.

She remembered being bayoneted, and being rescued by a soldier named Tschaikovsky who took her to Romania. They were married and had a child. When Tschaikovsky was killed in a street fight, she sent the child to an orphanage and gathered her courage to go to Berlin and ask Anastasia’s aunt, Princess Irene, for help. It was then that she lost hope and jumped off the bridge.

For the rest of her long life (she died in 1984), she attracted both adherents and detractors from among Anastasia’s royal relatives and the scientists and experts who examined her. Crown Princess Cecilie, the kaiser’s daughter-in-law and a distant relative of Anastasia, believed in Anna, but the princess’s son, Prince Louis Ferdinand, did not. Pierre Gilliard, who had been Anastasia’s tutor, believed at first and then later changed his mind. Grand Duke Alexander, cousin of the tsar, firmly believed.

Grand Duke Ernst of Hesse, who did not believe, conducted an investigation which concluded that Anna was actually Franziska Schanzkowska, a Polish factory worker who had disappeared in 1920. But Anna claimed to know of a secret trip that the grand duke had made to Russia in 1916 to visit the tsar. Ernst adamantly denied making any such trip, but in 1966 the kaiser’s stepson swore in court that he had been told that Ernst had indeed made such a trip. If Anna was an imposter, how could she possibly have known this?

The burial place of the Russian royal family was discovered and the remains removed in 1991. DNA testing confirmed that the grave had contained the bones of the tsar, his wife, and three of the children. Anastasia’s remains were not found. At yet another site were found charred bones that may be those of Anastasia and her younger brother.

Some men has plenty money and no brains, and some men has plenty brains and no money. Surely men with plenty money and no brains were made for men with plenty brains and no money.

—From the notebook of Arthur Orton

In the days before fingerprinting, photography, and Bertillonage, simple identification could be a confounding exercise. When a mother says that she recognizes her son, no matter how unlikely the body in which she finds him, how are we to argue?

The cargo schooner Bella was one of the first vessels to disappear in what has since become known as the Bermuda Triangle. It set sail from Rio de Janeiro, bound for New York City by way of Kingston, Jamaica, on April 20, 1854, carrying a cargo of coffee beans, a crew of forty, and one passenger—twenty-five-year-old Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne, heir to one of the oldest and richest estates in England. But the ship never arrived at either port, and neither did Mr. Tichborne or any of its crew. A bit of wreckage was found, but no further trace of the ship. Lloyd’s wrote it off as “foundered with all hands.”

In July 1855, Roger Tichborne was formally declared lost at sea. It should have ended there, but Roger’s mother, Lady Tichborne, was not one to give up easily. She placed ads in newspapers throughout Britain, America, Europe, and Australia in which she asked for word of her son. She described him as being rather undersized and delicate, with sharp features, dark eyes, and straight black hair. Many young men answered these ads, but none of them proved to be the missing Roger.

In 1862, when Roger’s father died and his baronetcy passed to Roger’s younger brother, Lady Tichborne began a fresh spate of advertising, offering a reward for information. An ad posted in the Melbourne, Australia, Argus read:

A handsome reward will be given to any person who can furnish such information as will discover the fate of Roger Charles Tichborne. He sailed from Rio Janeiro on the 20th of April 1854 in the ship La Bella, and has never been heard of since, but a report reached England to the effect that a portion of the crew and passengers of a vessel of that name was picked up by a vessel bound to Australia, Melbourne it is believed. It is not known whether the said Roger Charles Tichborne was among the drowned or saved. He would at the present time be about thirty-two years of age, is of a delicate constitution, rather tall, with very light brown hair, and blue eyes. Mr. Tichborne is the son of Sir James Tichborne, now deceased, and is heir to all his estates.

This appeal of course occasioned a new gush of sightings, claims, and stories. In 1865, Lady Tichborne was notified by the Missing Friends Bureau of Sydney, Australia, that a man answering her description had been found in the town of Wagga Wagga in New South Wales, where he ran a butcher shop and answered to the name of Thomas Castro. He said, however, that this was not the name given him at birth. A second letter confirmed that Castro was in fact a British nobleman in disguise, and that he had admitted to at least one person that he was really Roger Tichborne. Mama sent Andrew Bogle, an old family retainer, and Michael Guilfoyle, the erstwhile head gardener at Tichborne Park, both of whom had moved to Australia, to interview the butcher. Castro in the meantime had done his best to learn everything he could about Tichborne and the family history. Somehow, both Bogle and Guilfoyle accepted this fat, barely literate man as the slim, elegant, well-read Roger Tichborne.

The newly minted young Tichborne then wrote to his “Dear Mama” directly, proving himself unable to write a grammatical English sentence and to have trouble in spelling certain words, among them “Tichborne” (he spelled it “Titchborne”). He assured his mama that he had the birthmark (of which she had no recollection), and recalled an incident at Brighton (which she did not remember).

But poor Roger had been brought up in France, after all, and he always did have trouble with his English. And he never could spell very well. Almost convinced because she desperately wanted to be convinced, Mama sent him a return ticket to England. As she wrote to her Australian contact, “I think my poor, dear Roger confuses everything in his head, just as in a dream, and I believe him to be my son, though his statements differ from mine.”

But the man who returned was far from the son who had left. As Edward H. Smith put it, in Mysteries of the Missing:

She had sent away, thirteen years before, a slight, delicate, poetic aristocrat, whose chief characteristic was an excessive refinement that made him quite unfit for the common stresses of life. In his stead there came back a short, gross, enormously fat plebeian, with the lingual faults and vocal solecisms of the cockney. In the place of the young man who knew his French and did not know his English, here was a fellow who could speak not a word of the Gallic tongue and used his English abominably.

Of course she recognized him as her son immediately. They met in Paris, thus avoiding the young man’s British relatives until he had an opportunity to learn what he had to learn. He came, stayed, and learned fast. And Lady Tichborne was happy with her newfound son until she died some three years later in 1868.

The turns and twists of this story have filled at least a dozen books. Here we will follow the main thread until it reaches a sort of conclusion. In 1870 the Tichborne pretender filed suit to retrieve “his” birthright: the Tichborne estates and the baronetcy that went with them. He had used the intervening years to study up on everything Tichborne and to make friends with all the people whom he had supposedly known from childhood, using each new bit of information he unearthed as a lever to pry loose the next bit. It was noted that his handwriting grew more and more like that of the Roger Tichborne who had been on the Bella. Was he becoming more like his old self, or had he merely been practicing?

With the death of Lady Tichborne, the claimant had been cut off from his money supply, and the present heirs would not support his efforts to take the estate away. The case attracted a great deal of public attention, with the man in the street siding with the claimant. As the public saw it, greedy relatives were attempting to hang on to money that wasn’t rightfully theirs. After all, a mother should know her own son, shouldn’t she?

On May 11, 1871, a trial began that continued until March 1872. Sir John Coleridge, representing the family, questioned the chubby claimant for twenty-two days. More than a hundred witnesses took a hundred days to tell the jury that they knew Roger Tichborne, and that “that man over there” was he. Among the witnesses for the claimant were one baronet, six magistrates, one general, three colonels, one major, thirty noncommissioned officers and men, four clergymen, seven Tichborne tenants, and sixteen household servants.

The defense brought only seventeen witnesses, but they, along with the testimony of the claimant himself, carried the day. Sir John had exposed so many contradictions, distortions, absences of fact, and outright blunders that it became clear to the jury that the hundred witnesses who had testified for the claimant were mistaken. The claimant was immediately taken into custody, charged with three counts of perjury, and remanded for criminal trial.

Between the two trials the truth about the claimant came slowly to light. His real name was Arthur Orton. He was the son of a butcher residing at 69 High Street, Wapping, and had practiced the butcher’s trade himself in South America and Australia. After reading one of Lady Tichborne’s advertisements in an Australian paper, as a lark he had begun calling himself Roger Tichborne and assuming what he imagined were noble airs (mostly copied from music hall sketches).

At the criminal trial Orton was sentenced to fourteen years in prison and served nearly eleven—a couple of years were knocked off for good behavior. When he got out, he wrote up and sold an account of his “true story.” But he didn’t get much for it—by then the public had lost interest.

But Orton had done an impressive, almost credible job of fooling people. If he had not gone to court to try to claim the estate, he might well have remained a Tichborne for the rest of his life. The family might even have supported him in some meager manner if he had agreed to stay away. Consider that more than a hundred people who had known the real Roger swore in open court that Orton was indeed Roger returned. He took advantage of his time in England to visit all the places Roger had been, to practice Roger’s handwriting, to learn to walk and talk like a gentleman, and even to study French, though he could never manage to get the hang of it.

The time, expense, and notoriety of the trial, as well as Orton’s near success at pulling it off, clearly showed the British authorities that a better means of identifying people needed to be found.

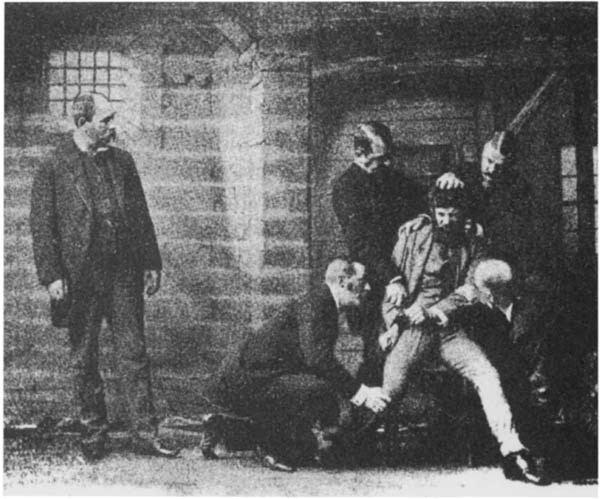

An infallible means of identifying those who, for whatever reason, were in the hands of the police was the goal, and the invention of photography brought it one step closer. As early as 1854, daguerreotypes of criminals were being made in Switzerland. A delicate process that uses wet plates and exposure times of up to two minutes, the procedure must have been trying on both the authorities and the suspects. In the 1860s the Paris commissioner of police, Lêon Renault, set up the first photographic studio intended specifically for police use. By the 1880s, after the development of more efficient dry-plate processes, photography became an essential police tool. Pictures of criminals were taken upon either apprehension or conviction, depending on the local laws. Photographs of habitual criminals were gathered together in large “rogues’ galleries” that were regularly studied by the police. A detective’s ability to memorize the faces of habitual criminals in his district was his most useful tool in crime detection and prevention.

The New York police persuade a man to have his picture taken, 1906.

Unfortunately, photographs did not prove as reliable as had been assumed. First offenders who happened to resemble habitual criminals were given harsher sentences than they deserved. And the reverse also occurred: in 1888 a convict in Manchester Prison serving a light sentence as a first offender murdered a warder; in the subsequent investigation it was found that he was a known criminal whose appearance had changed sufficiently to fool the camera.

What was needed was a foolproof means of telling one person from another—a measure of a man that would differentiate him from all other men. Ideally this would be something that could be easily measured, that would not change over time, and that could be codified and retrieved when needed. It wasn’t until the late 1870s that such a way was devised.