THE FIRST MAJOR STEP toward a scientifically rigorous means of criminal identification was taken by a civilian employee of the Paris police by the name of Alphonse Bertillon. In 1878, Bertillon was a records clerk in the Paris prefecture of police. His job made him acutely aware of the difficulty of identifying repeat offenders, and his family background suggested a possible solution.

Bertillon was born in Paris in 1853. Although this was an era in which scientists were making rapid forward strides, it was still possible for a generalist to contribute usefully to several fields of knowledge. Bertillon’s father, Louis-Adolphe, a descendant of a family of vinegar makers from Dijon, was a medical doctor as well as an anthropologist and statistician. The anthropologist Paul Broca, whose researches into the human brain first located the speech center, was a regular visitor at the Bertillon house and a sometime colleague of Dr. Bertillon.

From his childhood association with Broca and his father, the young police clerk had an intimate knowledge of the human skull. He first saw a way to apply anthropological studies to the work of the police when he heard of a theory of Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet (1796–1874).

Quetelet was one of those polymathic geniuses who seem so common to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A noted astronomer and mathematician, he was a founder of modern statistics, a method he developed in order to reduce errors in the measurement of stars. He was also an important innovator in the fields of meteorology, demography, sociology, and criminology, and was among the first to apply statistical methods to the study of human behavior. His most influential book was his 1835 Treatise on Man (or, as the French called it, Sur l’homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale).

Quetelet believed that the differences among individuals could be quantified, and that they fell along a normal distribution curve. His studies were among the earliest to show a relationship between crime factors such as age, gender, poverty, education, and alcohol consumption. He carried his theories of measurement of differences from the social realm to the physiological, observing that no two people have exactly the same body measurements.

Bertillon saw that if Quetelet was correct, it would be necessary to compare the measurements of two people only at a limited number of points in order to tell them apart. And if one kept a record of these measurements, one could identify a person with certainty if one ever had the occasion to measure him again. This seemed to Bertillon to have a direct application to the problem of identifying repeat offenders.

Bertillon worked out a system he called anthropometrics, but which his French compatriots came to call Bertillonage. Its three basic tenets were as follows:

1. That after about the age of twenty, the underlying bone structure of the human body is fixed.

2. That by using the right measurements one could differentiate every member of the human race.

3. That these measurements might be made with sufficient precision without undue difficulty.

In 1879, Bertillon took his idea to Prefect of Police Louis Andrieux, but the prefect’s response was less than enthusiastic: he threatened Bertillon with immediate dismissal if he continued to waste time on such a project. Fortunately for the future of anthropometrics, in 1882 Andrieux was replaced by Jean Camescasse, who gave Bertillon permission to conduct a three-month trial of his system. Two months and one week later, on February 24, 1883, Bertillon successfully identified his first recidivist. In 1883 he identified 43 recidivists, and in 1884 the number rose to 241. These successes were so impressive that a new service of judicial identity was formed, with Bertillon placed at its head.

The system that Bertillon developed had three components:

1. Measurements of the body: the height of the subject standing; his reach (the distance from fingertip to fingertip when the arms are outstretched); and the height of the subject when seated.

2. Measurements of the head: its maximum length from front to back; and the length and diameter of the right ear from upper left to lower right.

3. Measurement of the limbs: the length of the left foot; the lengths of the left-middle and little fingers; length of the left forearm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. The left side was chosen for limb measurements because it was believed to be less subject to changes from the stresses of physical work.

Bertillon constructed special stools and calipers in order to standardize the measuring process. Nonetheless the person taking the measurements had to be trained to do it correctly or the results would be anything but uniform. Even in the best of situations the measurements would vary from one taker to another. Bertillon was forced to publish a table of tolerances to allow for such errors. Another difficulty was the large number of criminals under twenty—their anthropometric measurements were still subject to the changes of maturation.

These anthropometric records would be useless without a specific record for comparison. The French criminalist Edmond Locard described the system that was devised thus:

The mass of a service’s files is divided into three groups, according to whether the length of the head is large, medium, or small. Each of the groups is divided into three subgroups according to the breadth of the head. Then each subgroup in its turn is subdivided into three classes by the length of the middle finger. And each class of middle fingers into three categories by the length of the ring finger.

In 1896, Ida Tarbell, a well-known and accomplished American journalist, wrote a long article on Bertillonage for McClure’s Magazine. When she interviewed Bertillon at his office in Paris, Miss Tarbell found him to be “a tall man of slightly haughty bearing. He had a grave face, of long regular lines; a dark, almost melancholy eye, with the slight contraction of the lids peculiar to serious students, and a nervous trick of knitting his brow.” His contribution to society, and particularly to forensic science, was unparalleled, she wrote. Bertillon was

the man who has so mastered the peculiarities of the human anatomy and so classified and organized his observations, that the prisoner who passes through his hands is subjected to measurements and descriptions that leave him forever “spotted.” He may efface his tattooing, compress his chest, dye his hair, extract his teeth, scar his body, dissimulate his height. It is useless. The record against him is unfailing. He cannot pass the Bertillon archives without recognition; and, if he is at large, the relentless record may be made to follow him into every corner of the globe where there is a printing press, and every man who reads may become a detective furnished with information which will establish his identity. He is never again safe.

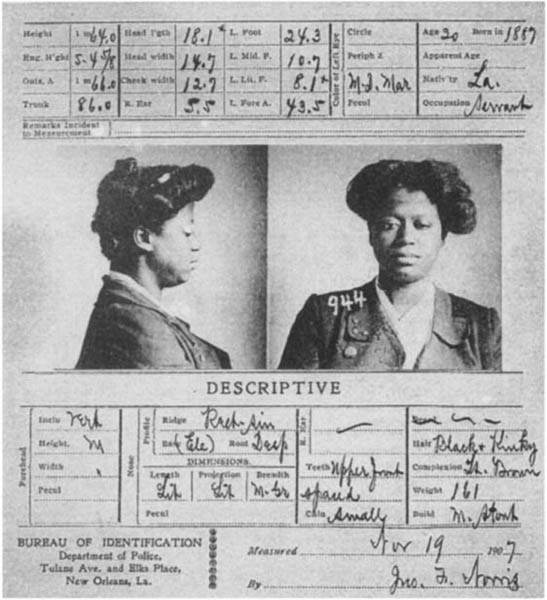

A Bertillon form used by the New Orleans Police Department, 1907.

After a short while Bertillon found it expedient to add a fourth element to his system: a pair of photographs, one in full and one in profile, taken with a special camera. Attached to the photography was a written description, a portrait parlé, that included items such as birthmarks, scars, tattoos, and noticeable deformities.

For a contemporary account of how the system worked, I again turn to Ida Tarbell, who had the privilege of watching as Bertillon’s anthropometrically trained officers measured a thief:

“Call the prisoner,” said my guide, M. David of the service, and immediately the guard brought in a short, rather stout man, clad only in undershirt and trousers. His feet were bare. His face was not at all disagreeable, and his eyes were bright and dark. He seemed to be perfectly indifferent to what awaited him, and gave his name and country without hesitation.

“He has been arrested for stealing rabbits at Robinson,” said my guide. “Our business is to find out if he has ever been up before. We’ll make the observations together, and you may record them on this card,” handing me a piece of card-board with many peculiar divisions and sub-divisions marked on it.

“Observations Anthropometriques” was the introductory heading, and “height” the first division. The prisoner was directed to place himself against a high measuring board, bearing at the side a scale. A flat board was placed across the top of his head, and the height it marked noted.

“Five hundred and fifty-eight,” said my guide. As I made my entry, a clerk in a high desk at the side repeated the number and wrote it in the book before him. “Of course,” said M. David, “it is understood that it is one metre, 55.8 centimetres” (five feet, 1.34 inches).

Without changing his position, the arms of the prisoner were stretched at full length, and the third measure taken—one metre, fifty-nine centimetres (five feet, 2.6 inches). The second measure, the curvature of the spine, is rarely taken. The fourth, height of the trunk, followed—eighty-three centimetres (two feet, 8.68 inches).

The next step was a little more complicated. The subject was ordered to sit down, and a jointed compass, furnished with a semi-circular scale divided into millimeters, was applied to his head, one foot being braced against the root of the nose, and the other moved over back of the skull, in search of the point of greatest depth. . . . After three trials the greatest depth was found, and 19.2 centimeters (7.56 inches) read out. In the same way the width was taken, 17.3 (6.8 inches), and then followed measurements of the ear.

“These measurements of the head,” said my guide, “are of extreme importance, because so sure. A tricky subject may expand his chest or shrink his stature, but he cannot add to or subtract from the length and breadth of the skull. And now for the foot.”

The prisoner was told to step upon a stool, and throw back the right leg in such a way that the entire weight should come upon the left foot. The measuring of the foot was followed by that of the left middle and little fingers and of the left forearm. “All good measures,” observed my conductor; “for the rule rests against the bones, and no dissimulation is possible on the part of the subject, and the chance for error on the part of the operator is little. And now for the eyes.”

The man was placed in a strong, full light, and told to regard the operator in the face. The latter then raised the left eyelid slightly, and seemed to be making mental notes of what he saw.

“But the eye changes,” I objected. “That man’s eye ought to be darker now, under the excitement of this examination.”

“False notion, that of the eye changing so much,” said my guide. “It is the ground of the iris which is affected chiefly by the light; and we do not base our classification on that. Here are the notes.”

“Class 3–4: aureole, radiant, of medium chestnut; periphery, of medium greenish yellow; two circles equal.”

“But where do you get all that information?” I queried. The gist of the answer I received was as follows:

The color of the eye is the result of the fusion of two elements, the shade of the ground of the iris and that of the aureole which surrounds the pupil. The usual method of classifying eyes in the past has been to regard them at a distance of three or four feet, and to mark the result of the fusion of the two elements. Eyes thus studied are classified as blue, brown green, and gray, or as dark, medium, light. But there is little precision in this method. M. Bertillon resolved to study the eye close ahand, and to analyze each of the elements. He found that the ground of the iris is rarely decided in shade, varying from a sky blue to a slate blue, and changing according to the intensity of the light and is, therefore, of little service in an exact description. The pigment of the aureole around the pupil is, however, more pronounced in color, and less variable in the light, and therefore better capable of serving as a basis of classification. By means of it the eye can be separated into seven sufficiently distinct classes.

(1). Pale, or without pigment; that is, an eye in which the aureole is absent or very insignificant, and in which the iris is marked by whitish striae.

(2). Yellow aureole.

(3). Orange aureole.

(4). Chestnut aureole.

(5). Maroon aureole in a circle or disk around the pupil.

(6). Maroon aureole covering the iris irregularly.

(7). Maroon aureole covering the entire iris.

Each of these divisions may be further divided into light, medium, dark, according to the shade. The sub-divisions approach closely sometimes; thus an eye may appear to one person as a dark orange, which to another will seem light chestnut.

When there is a doubt, the two classes are marked: thus, in the case of our rabbit man, the class was three or four. After the class is decided, the arrangement of the aureole is noted. Is it a solid, definite circle? Does it send off short rays? Do the rays touch the periphery? Do they cover the iris? Is it mottled by a different shade? All the mosaics, the festoons, the lace-like drapings of the aureole are noted. In the same way the color and the arrangement of the periphery of the iris are described. If there are striking peculiarities, they are added to the list.

“There are still two classes of points to be taken,” said M. David, “the descriptions and the special marks and scars; but we have now all that is essential. You may go,” to the prisoner.

The portrait parlé was also meant to stand alone as a verbal identification system. From his written description, a policeman trained in the portrait parlé could recognize a person in a crowd. But with hundreds of possible subdivisions and fine details, it took time and intelligence to master.

As originally devised by Bertillon, there were four major sections to the portrait:

1. A determination of the color of the left eye, hair, beard, and skin.

2. A morphological description of the various parts of the head, with emphasis on the right ear.

3. General considerations—body shape, carriage, voice, language or accent, clothing, apparent social standing, etc.

4. Indelible markings: scars, tattoos, birthmarks, and the like.

The recorder was to note peculiarities such as freckles and pockmarks. Hair could be light blond, blond, dark blond, brown, black, red, white, mixed grey, or grey. Baldness was also noted and described as either frontal, occipital, top-of-head, or full. Eyes were either blue, grey, maroon, yellow, light brown, brown, or dark brown. There were also various peculiarities of the eye—extremely bloodshot, eyes of two different colors, and arcus senilis, a white ring around the edge of the cornea.

And while the shape of the nose was of prime importance, it was by the ear that one might truly know the man. Barring accident, its shape is changeless from birth to death, making it the surest means of confirming identification by photograph. In its position and its angle on the head, the ear varies from person to person. It may take one of four general shapes: round, oval, rectangular, or triangular. Unlike Gaul, it is divided into six parts, the helix, the antihelix, the tragus the antitragus the lobule, and the concha. The helix is further subdivided: it may be either folded or flat and can form a variety of angles. The other parts also have distinct peculiarities that when added together account for tens of thousands of possible variations—a large enough number for preliminary elimination, but not large enough for positive identification.

Back to Miss Tarbell for a contemporary description of how the individual cards were classified and subsequently retrieved:

“To classify, we select the measures which are the surest [said her guide]; that is, those which do not vary with age; which the individual cannot change; which are the most valuable from one person to another, and which the operators make the fewest errors in taking. Experience has taught us that these are: (i) the length of the head; (2) the breadth of the head; (3) the middle finger; (4) the foot; (5) the fore-arm.” . . .

From the full card cabinet with ninety thousand cards, each representing one man or woman in the criminal catalog, the job was to find which card matched the man now being measured. With each division—the width of the head, the length of the middle finger to the first joint, the length of the foot, the length of the forearm from elbow to fingertip—the number of possibilities was reduced until it was down to a mere four hundred. Then, with the height and the length of the little finger added, the pack was winnowed down to about sixty. Next came the color of the eye, and the sixty was reduced to a dozen.

And last—distinguishing marks. A mole on his left arm? The prisoner rolled up his sleeve and there it was. Another mole on the wrist? There it was. They had identified their man.

At the time, the recording of distinctive marks—scars, moles, tattoos, and the like—was one of the strong points of Bertillon’s portrait parlé. But advances in surgery have made such things untrustworthy over time.

The portrait parlé was modified over the years into a simpler and more-or-less uniform identification form that was used by most police forces until the mid-twentieth century. One of Bertillon’s students, Harry Ashton-Wolfe, describes the advantages of the portrait parlé with enthusiasm:

One of the reasons why the layman cannot memorize a face in words is that he has no vocabulary to suit the need, and it is this vocabulary which was one of the first things the experts created. When we can describe a man as medium-tall, muscular, and corpulent; brachycephalic (round-headed) with low forehead; short, straight black hair coming to a point between bushy eyebrows; clean-shaven, with large ears set at right angles to the skull; eyes black, deep-set, small, and mobile; nose flat, with wide nostrils; fleshy lips; angry red bullet scar on left cheek; bulldog chin; abnormal canine teeth—we already have a mental picture of a simian, criminal type which would fix his unpleasant personality on our memory.

Bertillon advanced the science of photographic identification by a system he called metric photography, in which the camera, the lens, the distance of the camera from the subject, and the chair the subject sat in were standardized. He suggested a standardized reduction ratio of 1:7 for all photographs, so that the relative sizes of the subjects’ heads were immediately apparent. He also pointed out something that should not have needed mentioning—that the photographic negative should not be retouched to remove scars or blemishes from the subject’s face.

Bertillon worked out a method of improving the use of the camera in photographing crime scenes. He used standardized lenses, he took his pictures from standardized heights above the floor, and he printed on special paper imprinted with either an indoor or an outdoor grid, the outdoor grid allowing for distances to infinity.

Bertillon also made lesser-known but nonetheless important advances—the “galvano-plastic” method of preserving footprints found at the scene of the crime, for instance. Perhaps his only notable failure was his attempt to develop a system of handwriting analysis. Unfortunately he allowed himself to believe that he had succeeded. His aim was to identify forgeries or disguised handwriting and determine their author. Bertillon had studied the problem and developed some theories. His espousal of his incorrect ideas thrust him into the middle of an affair that became one of France’s greatest political and social crises.

On October 15, 1894, Captain Albert Dreyfus of the French army was arrested on a charge of treason. He was alleged to have written a letter (known throughout France as the bordereau [memorandum]) in which he offered to pass on secret information to the Germans. In fact Dreyfus was completely innocent. But he was a Jew at a time when the French army’s general staff was rabidly anti-Semitic.

The prosecutors asked Bertillon, the renowned head of the Paris prefecture’s Service of Judiciary Identity, to evaluate the bordereau. After a careful examination, Bertillon declared it a “self-forgery,” that is, that Dreyfus had attempted to imitate his own handwriting. He had done this presumably in order to argue that the document was a forgery in the event he were caught. Why he did not simply imitate someone else’s handwriting Bertillon did not say. Somewhere in the course of his investigation, Bertillon developed an idée fixe of Dreyfus’s guilt that warped his neutrality and thus his judgment.

Bertillon prepared a document showing where Dreyfus had employed a number of “deviations, shifts, or displacements” and had traced some of the words seven or eight times before writing them. According to Bertillon’s investigations, Dreyfus had even borrowed the shapes of certain letters from other members of his family. Jean Casimir-Périer, the president of the republic, given a demonstration of Bertillon’s conclusions, described Bertillon to a friend as “not merely bizarre, but completely insane, given to an extraordinary and cabalistic madness.”

Bertillon told the army that “The proof is there and is irrefutable. From the very first day, you knew my opinion. It is now absolute, complete, and admitting of no reservation.” The army wanted to believe. Dreyfus was convicted and sent to Devil’s Island. After two more trials and the fall of two governments, the identity of the real traitor, Commandant Count Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, was revealed. Dreyfus was exonerated and reinstated in the army in time to fight in World War I. The affair blighted the reputation of Bertillon and cast a shadow over his truly notable achievements.

While Bertillon identified criminals by measurements of their heads, the Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso (1836–1909), director of an insane asylum at Pesaro, Italy, took this system one step further. Misunderstanding Darwin’s theory of evolution, Lombroso decided that criminals differed from their more law-abiding brethren because of traits that were either atavistic or degenerative. Where the atavistic traits were throwbacks to an earlier stage of evolution, the degenerate ones had progressed in the wrong direction along the evolutionary line. Both types exhibited physical anomalies that made it possible to recognize them even before they committed the criminal acts they were doomed by their natures to perform. The atavists could be recognized by their subhuman characteristics—large jaw, a bulging brow, high cheekbones, and extra-long arms. According to Lombroso, these were “reminiscent of apes and lower primates, which occur in the more simian fossil men, and are to some extent retained in modern savages.”

The degenerates could be known by their congenital weaknesses and by their slack-jawed, unintelligent appearance. Tattooing, unless extremely minor, was another symptom of degeneracy. Lombroso used Bertillon’s anthropometric techniques to collect measurements of his “criminal types,” and believed he had found a meaningful correlation.

Many followers of Bertillon returned the compliment by firmly embracing Lombroso’s theories. As Harry Ashton-Wolfe explained:

Criminal faces, as the police and the laboratory experts understand them, are divided into three sections: those of degenerates or throw-backs, which vary little during their lifetime; those stamped with the evil characteristics which a career of crime inevitably evolves through constant association with others of the species and a frequent sojourn in penal establishments; and, finally, the faces which reveal Darwinian deformation and asymmetry of the features which, in many instances, may be merely some single strikingly abnormal development due to hereditary criminal tendencies.

For a while in the late i8oos Lombroso reigned supreme. Quoted everywhere, his doctrines were embraced by the criminal courts of Europe. “L’uomo delinquente” (the born criminal), believed to have more savage inclinations than the most savage ape, had better be put safely away for his own good and the good of humanity. Many who were accused of comparatively minor crimes received substantially longer sentences than their brethren because they had thick brows or long arms.

Bertillon himself wasn’t so sure, telling Ida Tarbell:

“No; I do not feel convinced that it is the lack of symmetry in the visage, or the size of the orbit, or the shape of the jaw, which make a man an evil-doer. A certain characteristic may incapacitate him for fulfilling his duties, thus thrusting him down in the struggle for life, and he becomes a criminal because he is down. Lombroso, for example, might say that, since there is a spot on the eye of the majority of criminals, therefore the spot on the eye indicates a tendency to crime; not at all. The spot is a sign of defective vision, and the man who does not see well is a poorer workman than he who has a strong, keen eyesight. He falls behind in his trade, loses heart, takes to bad ways, and turns up in the criminal ranks. It was not the spot on his eye which made him a criminal; it only prevented his having an equal chance with his comrades. The same thing is true of other so-called criminal signs. One needs to exercise great discretion in making anthropological deductions. Nevertheless, there is no doubt but that our archives have much to tell on all questions of criminal anthropology.”

But Bertillon, who seemed to have an ear fixation, averred that an infallible sign of either atavism or degeneration was a “striking asymmetry and malformation of the ears.” Lombroso’s later contention that genius was another form of degeneracy brought him into disrepute, especially among those who believed themselves to be geniuses.

The form of portrait parlé used in the United States before World War II, as recorded in Söderman and O’Connell’s Modern Criminal Investigation (1935), looked like this:

NAME . . .

SEX . . .

COLOR . . .

NATIONALITY . . .

OCCUPATION . . .

AGE . . .

HEIGHT . . .

WEIGHT . . .

BUILD—Large; stout or very stout, medium; slim; stooped or square-shouldered; stocky.

COMPLEXION—Florid; sallow; pale; fair; dark.

HAIR—Color; thick or thin; bald or partly bald; curly; kinky; wavy; how cut or parted; style of hairdress.

EYES—Color of the iris; eyes bulgy or small; any peculiarities.

EYEBROWS—Slanting, up or down; bushy or meeting; arched, wavy, horizontal; as to texture, strong; thin; short or long-haired; penciled.

NOSE—Small or large; pug, hooked, straight, flat.

WHISKERS—Color; Vandyke; straight; rounded; chin whiskers; goatee; side whiskers.

MUSTACHE—Color; short; stubby; long; pointed ends; turned-up ends; Kaiser style.

CHIN—Small, large; square; dimpled; double; flat; arched.

FACE—Long; round; square; peg-top; fat; thin.

NECK—Long; short; thick; thin; folds in back of neck; puffed neck; prominent Adam’s apple.

LIPS—Thick; thin; puffy; drooping lower; upturned upper.

MOUTH—Large; small; drooping or upturned at corners; open; crooked; distorted during speech or laughter; contorted.

HEAD—Posture of—bent forward; turned sideways; to left or right; inclined backwards or to left or right.

EARS—Small; large; close to or projecting out from head; pierced.

FOREHEAD—High; low; sloping; bulging; straight; receding.

DISTINCTIVE MARKS—Scars; moles; missing fingers or teeth; gold teeth; tattoo marks; lameness; bow legs; pigeon toes; knock-knees; cauliflower ears; pockmarked; flat feet; nicotine fingers; freckles; birthmarks.

PECULIARITIES—Twitching of features; rapid or slow gait; long or short steps; wearing of eyeglasses; carrying a cane; stuttering; gruff or effeminate voice.

CLOTHES—Hat and shoes—color and style; suit—color, cut, maker’s name; shirt and collar—style and color; tie—style and color; dressed neatly or carelessly.

JEWELRY—Kind of; where worn.

WHERE LIKELY TO BE FOUND—Residence; former residences; places frequented or hangouts; where employed; residences of relatives, etc.

PERSONAL ASSOCIATES—Friends who would be most likely to know of the movements or whereabouts of the person wanted, or with whom he would be most likely to communicate.

HABITS—Heavy drinker or smoker; drug addiction; gambler; frequenter of pool parlors; dance halls; cabarets; baseball games; resorts, etc.

HOW HE LEFT THE SCENE OF THE CRIME—Running; walking; by vehicle; direction taken.