THE PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILER is the new magician of forensic science. And as with magic, profiling provokes a variety of responses from observers and practitioners alike. The basic notion is simple. If you can think like a criminal, you can predict his actions. Or if you have many examples of his actions, you can form a clear image of the sort of person he is. Both of these notions have been tried, and on occasion they have worked exceedingly well. And sometimes they have not.

Probably the most infamous murderer of all times is the man known only as “Jack the Ripper.” He terrorized London for a few months in 1888, killing five women that we know of and possibly at least two more. The victims, all prostitutes working in the Whitechapel district of London’s East End, were killed quickly and brutally, some on street corners where anyone might walk by at any second—in one case it seems he was interrupted before he had finished. The victims were horribly mutilated, and with each killing the mutilation increased—the murderer took body parts away with him when he left the scene. After one killing he mailed half the victim’s kidney to the head of a Whitechapel vigilante organization, claiming in his letter that he had fried and eaten the other half. He ended his letter with the taunt, “Catch me if you can.”

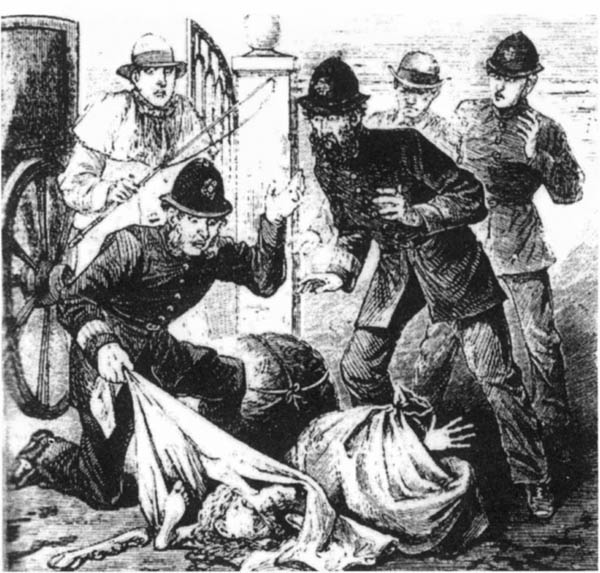

Another victim of Jack the Ripper in London’s East End.

Police surgeon Dr. Thomas Bond, who had assisted in the autopsy of Mary Kelly, one of the victims, was asked by investigators for a medical analysis of the wounds. In notes dated November io, 1888, Bond provided what today would be called a profile of the probable killer.

The killings, Bond asserted, had been committed by one man working alone. He was probably middle-aged, quiet, and inoffensive looking but nonetheless physically strong, composed, and daring. He dressed neatly and probably wore a cloak to hide any bloodstains resulting from his efforts. He would be a loner, without any real occupation, eccentric, and mentally unstable. He might suffer from Satyriasis (today we call it hypersexuality), and his acquaintances would be aware that he “was not in his right mind.” Bond was quite certain that the Ripper had a sixth victim, a prostitute named Alice McKenzie, though her wounds were unlike the others’. He thought that offering a reward for information might nudge someone’s memory or conscience.

Since the Ripper was never caught, the accuracy of Dr. Bond’s assertions cannot be known. Much has been written about the Ripper case and many theories cited as to who the Ripper was. None have been wholly satisfactory.

Before the days of official police profiling, there was the case of George Metesky (1904–1994), New York City’s “mad bomber.” He began his bombing before World War II, leaving his first bomb in a toolbox on a windowsill in a Consolidated Edison facility on West Sixty-fourth Street. That was on November 16, 1940. The bomb didn’t go off, and the bomb squad found a note wrapped around it: “CON EDISON CROOKS, THIS IS FOR YOU.” The presence of the note was puzzling, for if the bomb had gone off it would have been destroyed.

The unsuccessful bomber would seem to be a disgruntled employee or former employee of Con Edison. But Con Edison was vast. Except for a miniscule corner of Queens, it served all of New York City and most of Westchester County. And it was an amalgam of more than twenty earlier companies, some added only recently. The records of the employees of all these companies were scattered and poorly kept.

The next bomb also failed to go off. It was found almost a year after the first one, wrapped in a sock and lying on Nineteenth Street near a Con Edison office. Three months later Pearl Harbor was attacked, and New York, along with the rest of the country, had more important things to do than hunt down a maker of dud bombs. The bomber agreed, sending a letter to the police:

I WILL MAKE NO MORE BOMB UNITS FOR THE DURATION OF THE WAR—MY PATRIOTIC FEELINGS HAVE MADE ME DECIDE THIS—LATER I WILL BRING THE CON EDISON TO JUSTICE—THEY WILL PAY FOR THEIR DASTARDLY DEEDS . . . F.P.

And F.P. was true to his word. Apart from a few crank letters and postcards sent to the police, the newspapers, Con Edison, and random strangers, he was not heard from again until 1951, ten years later.

Over the years his bomb-making skills had improved, and his choice of targets became more grandiose. The first bomb of this new batch, and the first to actually detonate, was placed on the lower level of Grand Central Station. Luckily, no one was hurt in the explosion.

Evidently miffed that his bombs were getting so little publicity (the police were urging the newspapers not to play up the incidents), F.P. sent another letter, this time to the New York Herald Tribune:

HAVE YOU NOTICED THE BOMBS IN YOUR CITY—IF YOU ARE WORRIED, I AM SORRY—AND ALSO IF ANYONE IS INJURED. BUT IT CANNOT BE HELPED—FOR JUSTICE WILL BE SERVED. I AM NOT WELL, AND FOR THIS I WILL MAKE THE CON EDISON SORRY—YES, THEY WILL REGRET THEIR DASTARDLY DEEDS—I WILL BRING THEM BEFORE THE BAR OF JUSTICE—PUBLIC OPINION WILL CONDEMN THEM—FOR BEWARE, I WILL PLACE MORE UNITS UNDER THEATER SEATS IN THE NEAR FUTURE. F.P.

He went on to place more than thirty bombs over the next six years. His targets included Radio City Music Hall, the Capitol Theater, the Roxy Theater, the Paramount Theater, the New York Public Library, and Macy’s department store. In 1954 a second bomb at Radio City went off during a showing of Bing Crosby’s movie White Christmas, injuring four people. A bomb exploded in a toilet bowl in a men’s room at Pennsylvania Station, seriously injuring the seventy-four-year-old attendant who was trying to plunge out a bowl at the time.

While the bombs had not yet killed anyone, the bombings had injured quite a few people and were causing near-panic in the city. And the police were spending too much time following dead-end leads, searching for unexploded bombs, and attending to copycats and pranksters.

By 1956, after F.P. had planted his bombs for sixteen years, the authorities had neither caught him nor even developed any promising leads. This led the New York City police to call on the services of psychoanalyst James A. Brussel to create a personality profile of the mad bomber. After reviewing all the case material, Dr. Brussel started with the obvious:

—The bomber was paranoid.

—The bomber had a specific grievance against Con Edison.

—The bomber was male (well over 90 percent of bombers are male).

—The bomber was around fifty years old (paranoia classically peaks at thirty-five, and this had been going on for fifteen years).

—The bomber was a meticulous worker (the construction of the bombs showed that).

Then Dr. Brussel proceeded into the unknown:

—The bomber was not a native-born American. His use of language on the notes—“dastardly deeds,” “the” Con Edison—demonstrated this.

—The bomber probably had a high school education, but probably little or no college. This deduction was also derived from the language of the notes.

—The bomber was of Slavic origin and probably Roman Catholic. Eastern Europeans were known to use bombs, and most Slavs are Catholic.

—The bomber lived in Connecticut rather than New York. Many of the letters had been mailed from Westchester County, halfway between New York and Connecticut. There was a large Eastern European population in Connecticut.

Dr. Brussel also concluded that the bomber had an Oedipal complex. Therefore he was probably unmarried and might live with one or more female relatives, but not his mother.

Dr. Brussel threw in one last observation, “When you catch him,” he said, “and I have no doubt you will, he’ll be wearing a double-breasted suit.” Before the detectives could say anything he added, “And the suit will be buttoned!”

Then Dr. Brussel gave the detectives a piece of advice that went against their standard practices and all their police instincts: publicize these findings. Someone would come in or would have seen something useful. There was even the possibility that the bomber would see something he objected to in Dr. Brussel’s profile and call to complain.

So the police released Dr. Brussel’s profile along with other information about the bombings, holding back only a few details.

On Christmas Day 1956, acting on Dr. Brussel’s suggestion, New York City newspapers published a version of his profile of the bomber. The next day the New York Journal-American printed an open letter to the bomber urging him to turn himself in. The paper promised to publish his grievances and to see that he got a fair trial. F.R answered, listing all the places where he had planted bombs in the past year and saying, “My days on earth are numbered—most of my adult life has been spent in bed—my one consolation is—that I can strike back—even from my grave—for the dastardly acts against me.”

The Journal-American printed an edited version of his reply and followed it with a request that he tell its readers what his grievances were. He replied. He had been injured, he said, at a Con Edison plant, and had to pay his own medical bills; Con Edison had even blocked his worker’s compensation case. He went on:

When a motorist injures a dog—he must report it—not so with an injured workman—he rates less than a dog—I tried to get my story to the press—I tried hundreds of others—I typed tens of thousands of words (about 800,000)—nobody cared . . . I determined to make these dastardly acts known—I have had plenty of time to think—I decided on bombs.

He then sent a third letter, in which he revealed the date of his injury—September 5, 1931. Alice Kelly, a Con Edison clerk who had been going through old files, found letters from a George Metesky in a batch of denied workman’s compensation forms from 1931. She noted that words in his letters were similar to the ones in the bomber’s published replies. These included the phrase “dastardly deeds.”

New York police went to Metesky’s house in Waterbury, Connecticut, a little before midnight on Monday, January 21, 1957. They were accompanied by several local policemen and carried a search warrant.

Metesky answered the door in his pajamas. “I know why you fellows are here,” he told them. “You think I’m the Mad Bomber.” The detectives asked him what F.P. stood for, and he told them, “Fair Play.”

The detectives told him that they were taking him to the Waterbury police station, so he went upstairs to get dressed. When he came back down he was wearing a double-breasted suit, and it was buttoned.

The author and pop psychologist Malcolm Gladwell does not think that profiling is a science at all. With regard to Dr. Brussel and the Metesky case, he wrote:

Brussel did not really understand the mind of the Mad Bomber. He seems to have understood only that, if you make a great number of predictions, the ones that were wrong will soon be forgotten, and the ones that turn out to be true will make you famous. The Hedunit is not a triumph of forensic analysis. It’s a party trick.

But a double-breasted suit? Buttoned?

In 1943 the OSS (Office of Strategic Services), a wartime espionage service and precursor to the CIA, asked Dr. Walter C. Langer to develop a behavioral and psychological analysis of Adolf Hitler. They wanted to be able anticipate Hitler’s reactions to various war scenarios.

Langer used a number of sources to build up his profile—Hitler’s autobiography, Mein Kampf (My Struggle), his speeches, and interviews with people who had known him. In the resulting 135-page profile, Langer noted that Hitler was meticulous, conventional, and prudish about his appearance and body. He was not shy about describing himself, however. When Germany reoccupied the Rhineland in 1936, he said, “I follow my course with the precision and security of a sleepwalker.” This is hardly the description of a man in conscious control of his actions. And his estimation of himself was in little doubt: “Do you realize that you are in the presence of the greatest German of all time?” and “I cannot be mistaken. What I do and say is historical.” Langer predicted that in the event of the military collapse of Germany, Hitler would commit suicide. In 1945, hiding in his bunker in Berlin as the Russian army reached the outskirts of the city, Hitler shot himself.

On December 29, 1977, as Ambrose Griffin of Sacramento, California, headed from his car into his house with two sacks of groceries, he suddenly fell over. His wife thought he was having a heart attack and rushed him to the emergency room, where he died. The cause of death turned out to be wounds caused by two .22-caliber bullets. His wife then remembered hearing two popping sounds just as her husband collapsed.

The following day a news crew found two spent shell casings on the street outside Griffin’s house. Later that day a twelve-year-old boy reported that he had been shot at while riding his bicycle the day before. He said that the assailant drove a brown Pontiac Trans Am—twelve-year-old boys are good at identifying cars—had brown hair, and was probably in his twenties.

A woman living two blocks away reported she had been shot at in her house two days earlier. A .22 slug that matched the ones taken from Griffin was found in her kitchen wall.

Almost a month later, on January 23, 1978, twenty-two-year-old Theresa Wallin was savagely attacked as she took out the garbage. A bullet went through her hand, up through her arm, and out her elbow. A second bullet penetrated the top of her head. After she fell to the ground, the killer shot her again in the head, dragged her lifeless body inside and into her bedroom, and furiously assaulted it with a knife. She was stabbed repeatedly and cut open. Her spleen, kidneys, and intestines were pulled out. Then her kidneys were placed back inside her body. Her left nipple was excised. An empty yogurt container stained with blood was found near her body, as though someone had used it to gather and drink her blood. Bloody footprints were found in several rooms.

When Theresa’s husband came home after work and found his wife, who was three months pregnant, he ran from the house and could not stop screaming.

Sacramento police feared they had a serial killer on their hands and asked the FBI for help. Profiler Robert Ressler gathered the scant information that was known about the killer and suggested they look for a

White male, aged 25–27; thin, undernourished appearance. Residence will be extremely slovenly and unkempt, and evidence of the crime will be found at the residence. History of mental illness, and will have been involved in the use of drugs. Will be a loner who does not associate with either males or females, and will probably spend a great deal of time in his own home, where he lives alone. Unemployed. Probably receives some sort of disability money. If residing with anyone, it would be with his parents; however this is unlikely. No prior military record; high school or college dropout. Probably suffering from one or more forms of paranoid psychosis.

There are two kinds of serial killers—organized killers who plan everything methodically, and disorganized killers who plan nothing, act entirely on impulse, and scatter clues around their crime scenes. This one was clearly a disorganized killer, but clues like shoe prints are useful only when you have shoes to compare them to.

Four days later, on January 27, the neighbors of thirty-eight-year-old Evelyn Miroth grew worried when a little girl who had been sent to Miroth’s house on an errand reported that although she had seen some movement in the house, no one answered the bell. One of the neighbors entered the house, saw Evelyn’s fifty-one-year-old friend Dan Meredith lying dead in the hall, and immediately called the police. The first officer on the scene found Meredith with a gunshot wound to the head. He moved further into the house and found Evelyn in the bedroom. She was naked and shot through the head. She had been sodomized and then cut up in a fashion similar to that used on the body of Theresa Wallin. On the far side of the bed lay Evelyn’s six-year-old son Jason, shot twice through the head.

Evelyn had been baby-sitting for a friend, and now the infant was missing. A bullet hole was found in a pillow where the child had evidently been sleeping.

Dan Meredith’s red station wagon was taken by the killer and found parked a few blocks away with the keys still in it.

The police surmised that the killer lived within walking distance of where he had left the car and within walking distance of his victims—if he had stolen a car he had probably walked to the crime scene. A woman had told them of seeing a wild-eyed young man driving a red station wagon. Based on this description, they went around the neighborhood with a sketch of their suspect.

When Nancy Holden saw the sketch, it rang a bell. It looked to her like a boy she had gone to high school with. She would not have recognized him at all except that she had recently run into him in a shopping mall and thought that he had acted weirdly. His name was Rick Chase—Richard Trenton Chase.

Two officers went to Chase’s apartment, only a few hundred yards from where he had left the station wagon. Although they could hear him moving around inside, he refused to come to the door. They left but staked out the apartment and waited. Chase came out a while later, carrying a cardboard box and heading for his car. When the detectives tried to grab him, he threw the box at them and ran. They chased him and, after a violent struggle, subdued and handcuffed him.

They found a loaded .22-caliber pistol in his belt and a pair of latex gloves and Dan Meredith’s wallet in his pockets. In the cardboard box were bloodstained papers and rags.

The detectives took Chase to the police station, then, as he was being questioned, went back to search his apartment. The place was covered with bloodstains and strewn with feces. In the refrigerator were dishes holding human internal organs including brain tissue. There were three dog collars but no dogs. They later found out that Chase once bought dogs in order to kill them. On a calendar he had written “TODAY” across the dates of the Wallin and Miroth killings, with forty-four such dates yet to come.

The predictions of Robert Ressler, the FBI profiler, were eerily accurate. He accurately estimated Chase’s age. He was correct about Chase’s physical appearance, the appearance of his apartment, and the fact that mementos of the crimes would be found there. Chase indeed had an extensive history of mental illness, but given the nature of the crimes, this was probably the easiest of the predictions. He was a loner who used drugs and received disability checks. His mother paid the rent on his apartment. He was a college dropout.

During his questioning, Ressler asked Chase how he had selected his victims. “I go down the streets testing doors to find one that was unlocked,” he explained. “If the door was locked, that means you’re not welcome.”

Chase was clearly paranoid. He had been released from a mental hospital only months before taking up a gun and knife. Even when he was at the hospital, the other inmates had been afraid of him and kept away. Two staff members had quit after seeing him biting the heads off birds in the garden. Chase was convinced that his blood was turning to powder and that he had to drink fresh blood to stay alive.

Despite his history of grave mental illness, the prosecution at his trial was determined not to let him get away with an insanity plea. The jury complied, and on May 8, 1978, it found Chase guilty of six counts of first-degree murder. He was sent to San Quentin’s death row to await execution. While there his physical and mental health deteriorated, and he was sent to the facility for the criminally insane at Vacaville. On Christmas Eve 1980, Chase committed suicide by overdosing on anti-depressant pills he had hoarded from his daily dose.

Early in the morning of Wednesday, February 11, 1987, the mutilated body of thirty-seven-year-old Peggy Hettrick was discovered by a bicyclist on Landings Drive in Fort Collins, Colorado. At first he thought it was a mannequin lying in the field ahead of him. When he realized it really was the body of a woman, he called the police.

The coroner’s autopsy showed that Hettrick had been killed by a single stab to the upper left back. Her body had subsequently been sexually mutilated.

Fifteen-year-old Timothy Masters, who lived in a house next to the field, had also seen the body when walking to school that morning. He had not gone near it, also thinking it was a mannequin left there as a prank. When the police heard from his father that Timothy had walked through the field on his way to school, they pulled him out of class and took him to the station for questioning. The lead investigator, Fort Collins detective Jim Broderick, immediately settled on Masters as his primary suspect. The boy was grilled for well over six hours with no mention of his right to an attorney. In spite of Broderick’s aggressive tactics, Masters stubbornly refused to confess.

His room and school locker were searched, and a knife collection was discovered along with more than two thousand pages of his writings and drawings, many of “a pornographic and sadistic nature showing intense hostility toward women.” Police also found a newspaper article about the murder. Broderick became convinced of Masters’s guilt and would remain so for years despite all evidence to the contrary—there was not enough evidence for an indictment, much less a conviction.

Two hairs that were not Peggy Hettrick’s were found on her body, and fingerprints that were not hers were found in her purse. They were carefully compared to Timothy Masters’s, but they were not his.

The case eventually went into the cold case file, and Masters went on with his life. Five years later, in 1992, the Fort Collins police heard from a former high school classmate of Masters that when Masters and she had talked about the murder the week it happened, Masters had mentioned to her that Hettrick’s nipple had been cut off. This was one of the facts that had been withheld from the public.

On the basis of this new information, the police obtained an arrest warrant. Two officers flew to Philadelphia where Masters, who had joined the navy, was stationed aboard the USS Constitution.

“I probably told her that,” Masters admitted. “I heard it from a girl in art class.”

The detectives rushed back to Fort Collins to interview this girl, who admitted that she had told Masters about the missing nipple. She had been one of a group of explorer scouts that the police had asked to help search the field for Hettrick’s missing body parts. So Masters stayed in the navy.

In 1995, eight years after the murder of Peggy Hettrick, Lynn Burkhardt, a college student who was house-sitting for Dr. Richard Hammond and his family, spotted a camera lens concealed in the bathroom floor. Using a paper clip, she and a friend opened the locked door of Dr. Hammond’s “spare office” on the other side of the bathroom wall. Inside they found a mass of camera and electronic equipment along with a collection of pornography, much of it pictures of women sitting on the toilet of the bathroom next door. Some of these were close-ups of breasts and genitalia. The Hammond house was one hundred yards east of where Peggy Hettrick’s body was found.

When the Hammond family returned from vacation, Dr. Hammond was arrested for sexual exploitation. His wife told the police that she knew nothing of his secret room or his private hobby. She had been worried about him, however—he had recently begun collecting guns and knives.

Hammond was released on bail and checked himself into the Mountain Crest Hospital in Fort Collins for counseling. A few days later, the police were called to a motel in north Denver. Hammond had been found dead in his room. An intravenous needle containing cyanide residue protruded from his thigh. He left a suicide note that read in part, “My death should satisfy the media’s thirst for blood.”

At Detective Jim Broderick’s direction, the Fort Collins police destroyed all the evidence in the Hammond case. The fire burned for over eight hours. Miles Moffeit, a staff writer for the Denver Post, had this to say about Broderick’s decision: “Had Hammond been formally investigated and the evidence preserved, detectives might have been intrigued by parallels with the Hettrick case. . . . They might have searched Hammond’s warehouse specifically for Hettrick’s body parts. They might have tested his sex toys for DNA, as well as the knife on his belt. They might have matched his hairs with the two found on Hettrick.”

But Broderick wasn’t interested in Hammond; he was still focused on Masters. He had become convinced that the motive for the crime lay hidden in the mass of drawings that the police had confiscated from Masters on the day after the murder. He contacted forensic psychologist J. Reid Meloy, the author of The Psychopathic Mind: Origins, Dynamics, and Treatment and other books on the pathologies of criminal psychopaths. Meloy was interested in sexually motivated murders and had become an expert witness on the subject. He theorized that artwork can be a key to understanding the mind of a psychopathic killer. Not many professionals in his field agreed with him, but he was just what Broderick needed.

Meloy took a look at the pile of drawings Masters had done as a teenager and was prepared to testify that motivation had turned into action. “The killing of Ms. Hettrick translated Tim Masters’ grandiose fantasy into reality,” he wrote. He made this claim without interviewing or even meeting Masters. Meloy’s interpretation of a pencil sketch of a short man pulling another man as arrows fly toward them is bizarre.

Forensic psychologist J. Reid Meloy interpreted this drawing by Timothy Masters to be a depiction of the homicide he had committed.

This is not a drawing of the crime scene as seen by Tim Masters on the morning of Feb. 11 as he went to school. This is an accurate and vivid drawing of the homicide as it is occurring. It is unlikely that Tim Masters could have inferred such criminal behavior by just viewing the corpse, unless he was an experienced forensic investigator. It is much more likely, in my opinion, that he was drawing the crime to rekindle his memory of the sexual homicide he committed the day before.

And the fact that both figures are male? And the arrows? Meloy seemed unaware of Freud’s admonition that sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

Armed with Meloy’s willingness to testify about his suppositions, Broderick took the next step. On August 10, 1998, eleven years after Peggy Hettrick’s murder, Tim Masters, who had settled in California after leaving the navy, was extradited on a first-degree murder charge.

The trial began in March 1999. There was no new evidence and no physical evidence of any kind connecting Tim Masters to the murder of Peggy Hettrick in a field outside Masters’s house on that long-ago February day. There were only Masters’s teenage drawings and a man who called himself a forensic psychologist and admitted to an obsession with sexual killings.

At the trial, the prosecution projected grossly enlarged images of Masters’s drawings on the wall along with photographs of Hettrick’s body. The picture of the small man dragging a man’s body was one of Meloy’s favorites. How did he explain the arrows? Piquerism—a sexual aberration where one is gratified by stabbing or cutting with sharp objects.

Masters was convicted and sent to prison. By a 3–2 vote the Colorado Supreme Court refused to overturn the conviction. Justice Michael Bender, writing for the dissent, said, “Most of these writings and drawings have nothing to do with this grisly murder. The sheer volume of the inadmissible evidence so overwhelmed the admissible evidence that the defendant could not have a fair trial. . . . There exists a substantial risk that the defendant was convicted not for what he did, but for who he is.”

Five years into his prison sentence, Masters hired a new lawyer, Maria Liu, who quickly became convinced of his innocence. She was amazed that he had been convicted on such flimsy evidence. First, she wanted her own experts to examine the physical evidence. And the first step in this process was to have it preserved. Her motion to preserve was strenuously fought by the district attorney’s office. They argued, among other things, that “There is no statutory duty to preserve evidence.” In fact the two hairs found at the scene and the photographs of the unidentified fingerprints were already missing.

But Liu prevailed and took the medical examiner’s photographs of Hettrick’s injuries to Dr. Warren James, a Fort Collins obstetrician-gynecologist. He recognized the mutilations to the genitals as an actual surgical procedure. “Ms. Hettrick underwent a surgical procedure known as a partial vulvectomy,” he said. This was not a simple procedure, he told Liu. It required a “high degree of surgical skill and high-grade surgical instruments.” Powerful light would also be required, and the victim would have to be positioned with her legs apart. Tim Masters possessed neither the skill, the light, the privacy, nor the time to have done this.

On looking over the notes from the original investigation, Liu saw that even the medical examiner had called the cutting “surgical” at the time.

After a two-year court fight, Liu and her defense team finally got permission to have the remaining clothing from the crime scene sent to a lab in the Netherlands for DNA analysis. The forensic team there found no sign of Masters’s DNA, but they did find a stranger’s DNA on the inside of Peggy Hettrick’s panties.

After twenty years in prison, Masters was released in January 2008. Several of the officials involved in the original prosecution have been investigated for unethical conduct—it was found that they had not turned over a quantity of exculpatory evidence to the defense. When asked how he felt about being largely responsible for a twenty-year miscarriage of justice, J. Reid Meloy replied, “No comment.”