H

Haacke, Hans

(12 August 1936)

Born in Germany, Haacke came to America as an art-school teacher, eventually becoming a professor at New York’s Cooper Union, by common consent long consistently among the USA’s most regal art colleges. His principal esthetic achievement has been getting galleries to display artworks that emphasize deceits caused by corporate funding of the visual arts or the shady activities of certain art patrons. Descending from CONCEPTUAL ART, Haacke began in the early 1970s exhibiting maps with highlighted neighborhoods along with photographs of buildings held by Manhattan slumlords he viewed as particularly unctuous. (This prompted the cancellation of an announced exhibition of his work at the Guggenheim Museum and the firing of its curator Edward Fry [1935–92] in a scandal that decades later is not forgotten.)

Subsequent Haacke often uses the slogans from art-supporting corporations for ironic ends, such as a single horizontal aluminum plaque on which are polished letters with Alcoa’s president’s declaration, “Business could hold art exhibitions to tell its own story.” In addition to naming names, Haacke has been skilled at satirical retitling, such as calling PBS the “Petroleum Broadcasting Service.”

His recurring theme is exposing the connections between corporate bullies and art institutions. Though some Haacke admirers claim he made “unacceptable art,” his work is exhibited and discussed respectfully while he remains professionally employed, perhaps because exposé exhibitions –in contrast, say, to publication in newspapers –epitomize the finally safe enterprise of preaching to the converted.

Hába, Alois

(21 June 1893–18 November 1973)

Discovering sounds between the familiar twelve tones to a scale, he explored quarter tones, as he called them, in his Suite for String Orchestra (1917) and then in a large body of works incorporating not just quarter tones but fifth and sixth tones, for ensembles ranging from pianos to string quartets to operas. His theoretical treatises are available only through excerpts quoted here and there. In the mysterious politics informing modern-music performance, this innovative Czech’s works are largely more forgotten than those by his contemporaries: Americans such as Charles Ives and Henry Cowell, and certain Viennese.

Haldeman-Julius, E.

(30 July 1889–31 July 1951; b. Emanuel Julius)

By common consent the most influential alternative chapbook publisher ever in America, he established in Girard, Kansas, a unique business that printed miniature vest-pocket books 3½ inches by 5 inches, “Little Blue Books,” with uniform typographic covers on cheap pulp paper, stapled at their spines. Generally left-socialist in their orientation, these books he sold initially for twenty-five cents apiece before falling to ten cents and sometimes five cents mostly on newsstands, circumventing the censorship forever implicit in the more daunting economics of commercial hard-back book publishing. These chapbooks were also sent through the US Mail when postage costs were still minimal.

Starting with classic texts in the public domain, such as Shakespeare’s plays, EHJ eventually commissioned prominent serious writers to write simply on their favorite subjects –among them, G. B. Shaw, Will Durant, Bernard Russell, and Clarence Darrow. In sum EHJ issued some three thousand different titles and, knowing what many Americans wanted to read, sold innumerable millions of these chapbooks.

Think of him as a sort of HENRY FORD of serious/literary book publishing, as no one since has been as successful at distributing so much “progressive” literature so cheaply in any Western country. Though born in Philadelphia, EHJ moved to a Kansas town where his Bryn Mawr-educated wife and mother-inlaw owned a local bank.

My maternal grandfather (b. 1885), an immigrant from Asia Minor whose English was his fourth language, treasured them, while I own a few hundred of them. Politically active as well, EHJ ran as the Socialist Party candidate for the US Senate in 1932. Ahead of his time in other ways, Emanuel Julius added his first wife’s surname to his own for both himself and his eponymous publishing.

Halley, Peter

(24 September 1953)

Among those working in the wake of a previous generation’s discovery of CONCEPTUAL ART none wrote as well or as literately. The question then becomes whether Halley’s visual art embodies the high intelligence evident in his writings? Though he has exhibited and been reviewed for more than three decades, judgment remains inconclusive. These works tend to be at once obscure and allusive to higher degrees, less “ABSTRACT” than diagrammatic. Another question is whether art informed by European professors’ THEORY is therefore “academic,” even if realized by younger artists who aren’t tenured professors? In his intellectual sophistication, Halley falls into the esoteric tradition of visual artists Graduating From at Ivy League undergraduate colleges, thus including, among his predecessors, AD REINHARDT, EDWARD GOREY, PAUL LAFOLLEY, and FRANK STELLA. Halley also published the magazine Index from 1996 to 2005, later coediting a book culled from its pages (2014).

Halprin, Anna

(13 July 1920; b. Anna Schuman)

After studying with Margaret H’Doubler (1889–1982), a pioneer dance educator at the University of Wisconsin, Halprin emphasized nondance “natural” movements, improvisation, and process in both workshops and performances beginning in the late 1950s. Though she lived and worked around San Francisco, Halprin’s work was first recognized in European festivals in the early 1960s. Her stagings of Parades and Changes (1965), a complex and ever-varying piece, caused a scandal in the mid-1960s for its total nudity.

Halprin later became more interested in the therapeutic aspects of dance –in how it feels to the participant –than how it looks to an audience. In 1980, she began a community workshop called Search for Living Myths with her husband, LAWRENCE HALPRIN. She became committed to creating modern-day rituals –in exploring collective power, archetypal forms that emerge from groups, and the possibility for concrete results from the process of creation and performance. One such ritual –a performance of Planetary Dance (19 April 1987) –involved seventy-five groups in thirty-five countries. Not unlike other modern dancers who took good care of themselves, Anna Halprin performed into her nineties.

—with Katy Matheson

Halprin, Lawrence

(1 July 1916–25 October 2009)

The husband since 1940 of ANNA H ALPRIN, he studied conventional architecture before taking his advanced degree in landscape design. Commonly credited with helping develop “the California garden concept,” Larry Halprin subsequently expanded his range to, to quote his succinct summary of his career:

Group housing, suburban villages, shopping centers. Gradually these issues have aggregated into larger ones –how people, in regions, can live together in towns and villages without raping the land and destroying the very environment they live in. This led to concerns about transportation, both freeways for cars and mass transportation (BART), with particular concern for how these mammoth constructions could do more than just function as carriers, but go further and become forms of sculpture (as well as sociology) in the landscape.

Halprin’s ideas reflected, as they continually quoted, such artists as BUCKMINSTER F ULLER and JOHN C AGE, among others featured in this Dictionary.

Hamilton, Richard

(24 February 1922–12 September 2011)

A supremely adventurous and persistent British artist, he worked in several areas, some more successfully than others. Interpreting less than imagining, he drew often upon public information and images. In 1960, while MARCEL DUCHAMP was still alive, Hamilton produced a typographic version of the older artist’s original notes for the design and construction for The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors. Hamilton later made copies of his master’s often fragile oeuvre for exhibitions, including the legendary Large Glass long at London’s Tate Modern.

His appropriation of images from advertising, particularly a body-builder in 1956, marked him as a precursor of POP ART, notwithstanding a COLLAGE less than one foot square. Among Hamilton’s more ambitious projects, in progress for decades, were illustrations for JAMES JOYCE’s ULYSSES. His collaboration with DIETER ROTH was fecund and strong enough to be remembered in a solo book.

As Hamilton aged, his unusually long face with a long nose became his principal SIGNATURE. “A madden-ingly difficult artist to place,” to the British critic David Sylvester (1924–2001), this British treasure earned not one or two but a whopping three retrospectives at the august Tate Museum, not in its provincial branches, but in London itself, each exhibition significantly different from the others.

Hamilton Finlay, Ian

(28 October 1925–27 March 2006)

Would that I liked his work more, because he is among the few contemporaries to be honored in the histories of both contemporary poetry and contemporary visual art. He began as a conventional Scottish poet whose first book, The Dancers Inherit the Party (1960), contained traditional rhymed sentiments about people in the Scottish outlands. Within a few years, he had become the principal Scottish participant in international C ON-CRETE P OETRY, often writing poems that were just collections of nouns. An example is “Little Calendar”:

- april light light light light

- may light trees light trees

- June trees light trees light

- July trees trees trees trees

- august trees light trees light

- September lights trees lights trees

His next development was VISUAL POEMS that transcended the limitations of the printed page, some of them created in collaboration with professional craftsmen and visual artists. Many of these pieces began as additions to his home garden in Lanarkshire, a remote area he rarely left because he regarded it (and thus the works collected there) as a refuge from the cruel modern world.

As Hamilton Finlay’s work assumed more political themes in the 1980s (and he came into conflict with cultural officials over one issue or another), his pieces have often been included in thematic exhibitions that were installed outdoors. His five-acre home garden, Little Sparta in Lanarkshire, Scotland, became his masterwork. In the British tradition, his surname properly opens with the letter H.

Hammid, Alexander

(17 December 1907–26 July 2004; b. A. Hackenschmied)

Born in Austria, he grew up in Prague, making his first silent experimental film, Bezúčelná Procházka/Aimless Walk in 1930. After working as a cinematographer for the leftist American documentarian Herbert Kline (1909–99), he fled Czechoslovakia in 1939 to the US where he met and married Eleonora Derenkowskaya who took the name of MAYA DEREN, much as he too took a new name. In collaboration they produced the classic avant-garde film Meshes in the Afternoon (1943) that established her reputation that survived their divorce.

In the 1960s, Hammid began collaborating with the sometime painter FRANCIS THOMPSON on multi-screen films: To Be Alive (1964) and We Are Young (1967), which knocked me out at the Montreal EXPO 67, which remains in my mind as a masterpiece of the under-developed multi-screen cinema genre. Later Hammid and Thompson, among the great collaborations in expanded cinema, produced To Fly! (1976), which still stands the pioneering classic in the IMAX technology.

Handicaps/Disadvantages

One of the hidden truths informing avant-garde creation is that many major figures overcame severe professional limitations that would have defeated less determined people. After JOHN CAGE’s teacher judged that the aspiring composer had no talent for harmony, the younger man composed musics independent of harmony. As GERTRUDE STEIN lacked competence with conventional sentences, she wrote something else. As MERCE CUNNINGHAM was born too tight-jointed to make the flexible extensions favored by most dancers, he developed other movements as both a dancer and choreographer. As JACKSON POLLOCK was limited at his easel, he developed another way to apply painting to canvas. Many distinguished modern visual artists couldn’t pass an elementary class on “drawing.” My own juvenile efforts at linear prose fiction were dismissed by a novelist once prominent well before I produced radical narratives barely dependent upon imaginative “prose.”

One conclusion behind this observation is that certain major avant-garde artists courageously transcended a genuine lack of innate “talent,” sometimes because they develop a strong esthetic idea that incorporated an intelligence of its own. As the great Dutch footballer JOHAN CRUYFF understood: “Every disadvantage has its advantage.” Such achievement should be neither disrespected nor discouraged.

Happening

(1958)

Coined by ALLAN K APROW, a gifted wordsmith as well as an innovative artist, for his particular kind of nonverbal, MIXED-MEANS theatrical piece, this term came, in the late’60s, to characterize any and every chaotic event, particularly if it wasn’t immediately definable. Especially because the epithet had been vulgarized elsewhere, it became, within the community of visual performance, exclusively the property of Kaprow, who defined it thus:

An assemblage of events performed or perceived in more than one time and place. Its material environments may be constructed, taken over directly from what is available, or altered slightly, just as its activities may be invented or commonplace. A Happening, unlike a stage play, may occur at a supermarket, driving along a highway, under a pile of rags, and in a friend’s kitchen, either at once or sequentially. If sequential, time may extend to more than a year. The Happening is performed according to a plan without rehearsal, audience, or repetition.

Like all good definitions, this excludes more than it encompasses, beginning with some examples that one might think belong.

Hard-Edge Abstraction

See COLOR-FIELD PAINTING

Harlem Globetrotters

(1926)

Long the greatest comedians in “sports,” they gave their first PERFORMANCE not in a sports arena but in a night club, indeed a legendary ballroom, incidentally initiating an African-American basketball tradition not necessarily to win but to display athletic virtuosity, not only with individual stars but as a team. At a time when the professional basketball teams were lily white and visibly graceless, these African-Americans invented their own more theatrical style with witty ball-handling and delicate dribbling, including such awesome acrobatic moves as the above-the-rim dunks that DARYL DAWKINS later displayed in the National Basketball League. After the NBA color bar went down, white basketballers adopted some Globetrotter moves, playing “blackface,” so to speak, while “honest” basketballers, including certain NBA stars, joined the touring team from time to time. Later recruits to the Globetrotters have included women and very short players.

One defining individual in establishing theatrical excellence was Reese “Goose” Tatum (1921–67), famous as a long-armed “clown prince,” whom I first saw around 1955 and whose unique antics I have remembered ever since. Once Tatum retired, his crown was assumed by Meadow Lemon III (1932–2015), known as Meadowlark L. Collectively the Harlem Globetrotters developed delicious routines that could be performed over and over again without failure. Over the decades they have toured around the world, reportedly playing over 25,000 “games” that don’t require translation, pleasing adults as well as children, in tandem with mostly Caucasian opponents, who are fated to lose. While imitators have come and gone, the HG’s virtuosic comedy survives. Odd it is perhaps that nothing comparable has succeeded in other team sports.

Hartley, Marsden

(4 January 1877–September 1943; b. Edmund H.)

Even through few prominent American painters of his generation wrote as well and no writer publishing both so much poetry and criticism painted, his professional and personal life required endless struggles. Hartley moved frequently not only through the eastern United States but also in Paris and BERLIN, rarely establishing permanent residence let alone permanent relationships. So impoverished was he in 1935 that he sadly burned many earlier paintings sooner than pay storage costs. Nonetheless, among Hartley’s poems “Diabolo” (1920) is particularly memorable, and few critics of his time wrote as well, if selectively, about art, literature, and American PERFORMANCE. As his strongest paintings reflect homosexual desires that would be less problematic a century later, it could be said that Hartley came and went too soon. After ROBERT INDIANA relocated from New York City to Maine, where he purchased property that Hartley previously inhabited, the artist younger by a half-century produced Hartley Elegies (1989–94) that channel as they implicitly enhance his predecessor. Sadly, the last major traveling (semi)retrospective of Hartley’s work, initiated in 1980 by New York Whitney Museum, acknowledged his substantial writings only in the catalog’s concluding pages (pp. 209–211), implicitly diminishing his achievements.

Hartmann, Sadakichi

(8 November 1867–22 November 1944; b. Carl S. H.)

Given how much immigrant intellectuals have always contributed to American arts history, it is scarcely surprising that the first major critic of photography, among other arts, should have been born in Japan of a German father and raised in Germany before arriving in Philadelphia as a teenager. An adventurer in the arts, Hartmann was an accomplished dancer who looked like no one else. Working in live theater, he introduced perfumes into his staged performances (that received negative notices); he was a DOWNTOWN Manhattan art celebrity whom GUIDO BRUNO crowed “The King of the Bohemians.” Though largely self-educated, Hartmann was for several years a prolific reviewer of new art for American newspapers. He founded a periodical called The Art Critic (1893) that survived only four issues; he published in 1910 an early full-length book on James McNeil Whistler (1834–1903). Unique by several measures, he also wrote poetry and plays about Jesus Christ, Buddha, and Confucius, a trilogy that was reprinted as late as 1971. Once Hartmann moved to Hollywood, he appeared in films, most memorably as the Court Magician in The Thief of Bagdad (1924). Hartmann’s best extended photography criticism, from the beginning of the 20th century, is remembered on PCCA (Photography Criticism CyberArchive) sponsored by A. D. Coleman (1943), a major independent American photography critic of a later generation.

The Hasty Papers

(1960)

A great American one-shot literary/art magazine/ anthology, this appeared in a large format, 11 inches by 14 inches, on newsprint; its publisher was Alfred Leslie (1927), nominally a painter. Its contents included “When the Sun Tries to Go On,” which remains for me KENNETH KOCH’s greatest single poem, actually written several years before; fresh contributions from PONTUS HULTÉN, W.C. WILLIAMS, JOHN ASHBERY, ALLEN GINSBERG, JACK KEROUAC, in addition to two curious texts whose inclusion later seems reflective of the time: Fidel Castro’s 1960 speech to the United Nations and the complete 19th-century American classic, Fitz Hugh Ludlow’s The Hasheesh Eater (1857). Though reflective of DOWNTOWN Manhattan, The Hasty Papers was reprinted intact in 2000, on better paper, a hardback classic of a classic, by a small press in Texas. Nothing comparably spectacular has appeared since, not even in NEW YORK CITY; even for Alfred Leslie, doing as well again would have been daunting.

Hausmann, Raoul

(12 July 1886–1 February 1971)

Born in Vienna, Hausmann spent his teen years in BERLIN, where as a young man he met Johannes Baader (1875–1955), who joined him and RICHARD H UELSENBECK in founding the DADA Club in 1918. Already in his thirties, Hausmann soon afterwards became, in MARC DACHY’s summary, “painter, craftsman, photographer, creator of photomontages, visual concrete poet, sound poet, theoretician, prose writer, technician, journalist, historian, magazine editor, dancer, and performer,” which is to say a POLYARTIST.

In 1919, Hausmann started the periodical Der Dada and organized the first Dada exhibition in Berlin. Politically radical, he allied with Baader in placing fictitious articles in Berlin daily newspapers and in proposing a Dada Republic in the Berlin suburb of Nikolassee, announcing their political activities through eye-catching posters.

Hausmann invented the Optophone, which was a photoelectric machine for translating kaleidoscopic forms into sound, and also created the Dada “phonetic poem” before KURT S CHWITTERS took the idea to a higher level, the former’s performance in 1921 of his “FMSBW” reportedly influencing the latter. “The sound poem,” according to Hausmann, “is an art consisting of respiratory and auditive combinations. In order to express these elements typographically, I use letters of different sizes to give them the character of musical notation.” Hausmann probably invented PHOTOMONTAGE before MOHOLY -N AGY and JOHN H EARTFIELD. His polyartistic career is best defined by an English epithet more popular in Europe than America: “multiple researches.”

Heartfield, John

(19 June 1891–26 April 1968; b. Helmut Herzfeld)

The son of a socialist poet, he anglicized both his names in 1916 as a protest against forced military service in World War I and, under this new moniker, produced advanced art. As a founding member of BERLIN Dada, calling himself Monteurdada, he joined Rudolf Schlichter (1890–1955), in hanging from the ceiling Prussian Archangel (1920), a shop-window dummy dressed in a German officer’s uniform and fitted with a pig’s head. Heartfield differed from his politically dissenting colleagues by actually joining the Communist party, inadvertently inviting some antagonistic journalists to equate Dada with Bolshevism, which otherwise wasn’t generally true.

Later an early adventurer in P HOTOMONTAGE, Heartfield specialized in visually seamless cutups that ridiculed Fascist politicians. These were published as cartoons, posters, illustrations, and book covers (a format that he particularly revolutionized) –wherever he could, in his aspiration to be a popular political artist. Heartfield’s most famous image is Adolf, Der Über-mensch: Schluckt Gold und redet Blech (1932), depicting Hitler swallowing large coins and spewing junk.

Once Hitler took power, Heartfield fled to Prague and then to London (while his brother, Wieland Herzfelde [1896–1988], a prominent publisher, escaped to New York City). After settling in East Germany in 1950, John Heartfield, his name still English, received all the benefits and privileges that a communist state could offer.

Heidsieck, Bernard

(30 November 1928–22 November 2014)

A pioneering sound poet, whose spoken work realized a propulsive voice instantly identifiable as his, Heidsieck pursued from the early 1950s a singular path focused upon French language and French history, usually with identifiable subjects, producing many tapes and records as well as books that include 7-inch records and even films. He coined the epithets “poésie sonore” in 1955 and “poésie action” in 1962, the first an approximation of SOUND POETRY, the second of performance poetry. He began to work with audiotape recorders as early as 1959. He was credited with organizing the first international festival of sound poetry in 1976. Heidsieck was one of the few writers mentioned in this book ever to win a major prize from his own government (in his case, the Grand Prix National de la Poésie [1991]); one explanation held that the literary judges, initially divided over more conservative candidates, picked Heidsieck to take revenge on one another. Such fortuitous accidents happen in the history of rewarding the avant-gardes.

Heilig, Morton

(22 December 1926–14 May 1997)

A cinematographer/documentarian famously way too far ahead, he published in 1955 an extraordinarily visionary proposal for “The Cinema of the Future” whose images would surround the spectator. More practically, he developed in the 1960s a patented projection technology that he called Sensorama to create for spectators a multi-sensory enveloping experience, offering the viewer not only images and stereo sound but breezes and even smells. Heilig’s classic short film/projection, vividly recalled in Howard Rheingold’s Virtual Reality (1991), took the viewer on a highly sensuous motorcycle ride through Brooklyn including the experience of headwind and exhaust fumes. (A comparable later development, done by others and called The Sensorium and prophetically billed as a “4D film,” was screened in a Baltimore amusement park in 1984.) Whole books of modern film history have appeared without Heilig’s name.

Heiss, Alanna

(13 May 1943)

A visionary servant of art, she discovered in DOWNTOWN Manhattan spacious empty spaces, usually in city-owned buildings, that, thanks to her passion and negotiating skills, could be made available to artists to use as working studios. She began in 1972 with upper floors of a building on the corner of Leonard Street and Broadway, famed for its rooftop clocktower whose dial was stuck, and so officially incorporated Clocktower Productions as a nonprofit. On floors below, all visitors remember, were New York City offices like parole boards. Heiss identified other empty spaces, some of them only temporarily available, and then a whole empty school in the outer borough of Queens, the original P.S. (Public School) # 1 that, permanently available, offered larger exhibition spaces in addition to production studios in former classrooms, initially for local artists, later for beneficiaries from around the world. With a sure sense of herself as an ART WORLD star, Heiss ran this PS 1, as it was commonly called, from 1976 to 2008 as the most visible ALTERNATIVE SPACE. (I had at the beginning there a BOOK-ART exhibition in a smaller corner ground-floor room that had obviously been a principal’s office. On the wall was still a box for controlling the ringing of bells within the school.) From its modest origins P.S.1 eventually became an official outpost of MoMA just across New York’s East River.

Heissenbüttel, Helmut

(21 June 1921–19 September 1996)

Initially a student of architecture, art history, and “Germanistik,” he was regarded as one of the foremost exponents of post-World War II German avant-garde writing. An influence upon the new poets of the 1960s (Peter Handke [1942] and FRANZ M ON, among others), he approached poetry, as well as his prose, from, in his words, a linguistically “an-anarchic” point of view. His poems are calculated, experimental, and carefully crafted, occasionally including lines in English or French. He called them “texts,” and thus his collections, literally, “textbooks.” His writings often deal with trivia, with thoughts anyone could have in the course of a day, in a language as ungrammatical as everyday language can be; once spelled out, such thoughts become generalized and yet are alienating.

His novels, usually called “projects,” are mostly parodies of historical events. In Wenn Adolf Hitler den Krieg nicht gewonnen hätte (If Adolf Hitler Had Not Won the War), Hitler and Stalin have triumphed, and Europe has become a socialist computer society whose totalitarian government lets superfluous people die for the sake of economic advantage. Triangular relationships among Friedrich Nietzsche, Paul Rée, and Lou von Salomé become the center of 1882. Eine historische Novelle (1882, an Historical Novella). Das Ende der Alternative, Fast eine einfache Geschichte (The End of the Alternative, Almost a Simple Story) tells about a beautiful, tall woman, the “alternative,” who commits suicide by drowning herself in the ocean after several attempts to kill her have failed. Heissenbuttel also worked from 1959 to 1981 as the director of “Radio-Essays” at the Stuttgart radio station.

—with Michal Ulrike Dorda

Heizer, Michael

(4 November 1944)

Count this American artist Heizer, along with ROBERT S MITHSON and RICHARD L ONG, the principal proponents and practitioners of Earth Art. He shares with Smithson a taste for executing projects on a grand scale. What distinguishes his work from that of Smithson is the paradigm from which it proceeds. Smithson’s projects accompanied a complex intellectual program built on sophisticated esthetic and scientific ideas. Heizer’s alterations of the landscape are designed to reinvigorate the traditional sensibility of the sublime, invoking the breathless and expansive sense of awe instigated by the monumentality of mountain vistas. The shortcoming of his method is that, as with most works of Earth Art, his projects are generally seen through photographs in gallery exhibitions, and there they have the dryness of documentary records. In Heizer’s Displaced/Replaced Mass (1969), three boulders were dynamited 9,000 feet up in the Sierra Mountains, and the pieces were carted down to a desert plain and loaded into prepared holes. For the typical viewer, the project is just an idea, and the photographs convey an experience others have had. His Double Negative (1969), in which two deep trenches were cut into a desert cliff, might well induce a sense of natural wonder in the face of its towering walls, but only if one were actually there. Unlike many Earth Artists, Heizer continued to execute his large-scale projects into the 1980s, most notably in Effigy Tumuli (1983–85) and City: Complex Two (1980–88). Since that time, he has focused on object-based sculptures presented in gallery spaces. They have been, for the most part, works in stone and in steel, large and simple forms such as large, smooth boulders and enormous biomorphic shapes perforated with holes.

—Mark Daniel Cohen

Held, Al

(12 October 1928–27 July 2005; b. Alvin Jacob H.)

Because he painted in various ways, persistently unfashionable, he was never an art star but a major minor player, indeed a persistently major minor player, in a competitive world with few seats available for widely acknowledged stars. Some of his earlier painting had ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST fields within geometric pigeonholes, implicitly synthesizing JACKSON POLLOCK with PIET MONDRIAN. For one innovative move, in series titled C60 (1960), Held applied black ink with a thick brush producing on paper images reminiscent of FRANZ KLINE but different in texture, thanks to Held’s preference for ink over paint. His masterpiece is the Alphabet Paintings (1961–67) that are letters drawn large, very large, with sharp edges on huge canvases. The I (1965), for instance, is 9 feet high and nearly 6½ feet across. Circle and Triangle (1964), from the same period, is 12 feet high by 28 feet wide, its black image both protruding and receding against a white background. In the par-lance of boxing, they knock-out.

Helms, Hans G.

(8 June 1932–11 March 2012)

Around 1969, I met in New York this German writer who, in the course of discussing something else in my East Village living room, claimed to have written a polylingual novel. Skeptical, I replied, “not bilingual, like Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange [1961].” His response was in an awesome number of languages. This book, Fa:m’ Ahniesgwow (1959), comes in a box with a 10-inch record on which the author reads selected pages. Some pages are predominantly German, others predominantly English. My own sense is that, like JAMES J OYCE before him, Helms made linguistic decisions based on sound and rhythm. The disk reveals that in his Sprach-Musik-Kompositionen (language-music compositions) Helms hears white space as silence. The book concludes with extensive notes (in German only, alas) by his colleague Gottfried Michael Koenig (1926), himself a noted German composer, who sees the book’s title, for instance, ingeniously combining English, Danish, Swedish, South American Spanish, and North American slang.

Around the same time, Helms produced Golem, a speech PERFORMANCE that he characterizes as “polemics for nine solo vocalists.” His Text for Bruno Maderna (1959), an Italian composer, consists entirely of phonemes, while later Helms speech-music incorporates SERIAL organizing principles to phonemes and morphemes.

A prodigious adventurous figure, Helms also worked as a jazz saxophonist in Sweden in the early 1950s, published Marxist social criticism, produced extended features for both radio and television stations in Germany (including memorable conversations with JOHN CAGE), and, in his last years, reportedly investigated the history of Jews in Eastern Europe.

Henry, Pierre

(9 December 1927–5 July 2007, pronounced EN-ree)

Pierre Henry specialized in MUSIQUE CONCRÈTE for several decades, producing many of its classics remarkable for their liveliness and originality. Born in Paris, he grew up in the countryside, then studied composition with Nadia Boulanger and OLIVIER M ESSIAEN at the Paris Conservatoire (1938–48), where he also trained as a pianist and percussionist. From the beginning his interests turned toward rhythm and “noise” –placing him in the tradition of L UIGI

RUSSOLO and EDGARD V ARÈSE. Henry experimented not only with percussion instruments, but also with preparing the piano, which he began doing in the late 1940s, initially without any knowledge of JOHN C AGE. Henry’s approach to preparing the piano was quite different from Cage’s, as his preparations were more extreme and deliberately crude, and incorporated larger objects; the result was not the delicate, controlled gamelan-like effects of Cage’s prepared piano, but sounds that were clattering, chaotic, and noisy. This distinctive element recurred in Henry’s compositional universe; it was centrally featured, for example, in his homage to Russolo, Futuristie (1975).

Figure 7

Pierre Henry’s home studio in Paris.

In 1949 Henry met Pierre Schaeffer (1910–95), a radio engineer who the year before had produced the earliest examples of musique concrète –short studies created out of manipulated recordings of environmental or instrumental sounds. Schaeffer invited Henry –who in the end proved a far more fertile composer –to join him at his studio, and together they produced the first masterpiece of ELECTRONIC MUSIC in general: Symphonie pour un homme seul (1949–50). This title, which translates as Symphony for a Man Alone, is not intended to suggest the isolation of man in modern times, but refers, rather, to the fact that a single person could “perform” all the parts of this new kind of symphony. From its relatively modest beginnings in the late 1940s, Henry’s musique concrète –or, as the genre is now usually referred to, electroacoustic music –grew in complexity and power.

In Henry’s large body of work there is great variety, but also a certain recurring atmosphere of ritual and incantation. It is no accident that several of his pieces are secular masses, i.e., the Messe de Liverpool (1967–70) and the Messe pour le temps présent (1967). There is also an underlying physicality, expressed in strong rhythms and reflecting the origin of much of Henry’s electroacoustic music in recordings of his own instrumental performances. This has led him to create scores for many ballets (notably for choreographer Maurice Béjart) and theatrical events, the latter sometimes conceived in their entirety by himself. He has also shown great open-mindedness in his collaborations with rock and pop musicians, which are sometimes successful (Messe pour le temps présent, or Paradise Lost [1982]), and sometimes not (Cérémonie [1969]).

—Tony Coulter

Hepworth, Barbara

(10 January 1903–20 May 1975)

Along with HENRY M OORE, Hepworth was one of the two premier British sculptors of the middle of the 20th century. Their works were very similar: smooth, simple, biomorphic shapes that both artists frequently pierced through. Hepworth often ran parallel lines of strings through the center hole, giving her sculpture a further similarity to the works of NAUM G ABO. The closeness to Moore is the most evident, but what Moore was to the figure, Hepworth was to landscape. Moore almost always abstracted the human form, leaving it sufficiently evident that his subject matter is unmistakable. Hepworth dealt in pure abstraction, developed out of her experience in nature. She extracted the properties of topography: open shapes, enveloping curves, cavernous concavities, the stretching arms of a coastline. Re-creating these properties as pure form, Hepworth aestheticized the landscape mode, which was an accomplishment utterly different from Moore’s.

—Mark Daniel Cohen

Herriman, George

(22 August 1880–25 April 1944)

Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strip is the zenith of the form. Krazy Kat (sometimes male, but more frequently female) loved Ignatz Mouse, and the scatterbrained Krazy always believed that a brick thrown at her head by Ignatz was a sign of his love. The newspaper-reading public did not eat this up. All of the adventures of Krazy Kat took place in the mythical Kokonino Kounty, a desert decorated with weird geological and botanical forms. Herriman’s genius, however, accounted for more than the strangeness of the physical landscape he developed or the emotional landscape of his characters. His experiments with the form of the comic strip were what made his work remarkable. Panels were inserted into panels, overlaid upon panels that served as establishing shots, or laid askew of the defining grid. Colors were used not logically but brashly. The fiction of the comic strip was laid bare by visual puns that broke through the wall of the newspaper and made clear the other reality that the characters lived within. Herriman explored, as fully as anyone has, the esthetic possibilities of the comic strip through design, language, color, and characterization. The sense that no one has ever surpassed his work indicates how confining the modern strip format is –remember that Herriman had a whole newspaper page to work with, and occasionally only one panel filled that space –and how conservative the comic strip syndicates have become.

—Geof Huth

Herschkowitz, Filipp Moiseevich

(7 September 1906–5 January 1989)

Born in Rumania, he lived from 1927 to 1938 in Austria, where he studied with ARNOLD SCHOENBERG’s pupils –Alban Berg and ANTON WEBERN. When the Nazis occupied Austria, he returned to Rumania and from there immigrated to Russia, where the composer lived, stuck mostly in Moscow, from 1939 to 1987. Forbidden to teach serial composition in Stalinist Russia, he nonetheless had private students and personal contact with a younger generation that became more prominent in the post-Soviet years, including Edison Denisov (1929–96), Alfred Schnittke (1934–98), and Sofia Gubaidulina (1931). Finally allowed to leave the Soviet Union in 1987, Herschkowitz spent the last two years of his life preparing Alban Berg’s works for publication. He is the epitome of a brilliant modern outsider unfortunately stuck in the wrong place at the wrong time, thus forbidden to realize his professional potential.

Hertzberg, Hendrik

See O’ROURKE, P. J.

Hesse, Eva

(11 January 1936–29 May 1970)

Born in Hamburg, Hesse fled in 1939 to New York with her educated and cultured family. In her brief career as a sculptor, cut terribly short by terminal brain cancer, Hesse discovered the feasibility of using several materials previously unknown to three-dimensional visual art. After dark gouaches of 1960–61, whose motifs presage later sculptures, she made reliefs and sculptures in grays and blacks. The classic Hesse work, Expanded Expansion (1969), has vertical fiberglass poles, several feet high, with treated cheesecloth suspended horizontally across them; her rubberizing and resin treatment gives cloth a density and tension previously unavailable to it. Given the essential softness of her materials, the sculpture would necessarily assume a different look each time this work was exhibited. Though Expanded Expansion is already several feet across, there is a suggestion, which the artist acknowledged, that it could have been extended to surrounding, thus E NVIRONMENTAL, length. Reportedly destroyed, the work may never be exhibited again, its mythic status notwithstanding. Hesse also used latex. In part because she was, along with LEE B ONTECOU (1931), among the first American women sculptors to be generally acclaimed, Hesse also became, posthumously alas, a feminist heroine.

Hicks, Edward

(4 April 1780–23 August 1849)

This early American artist becomes inadvertently interesting for painting roughly the same scene with the same title for at least sixty-two paintings, none of them otherwise identical. The theme of The Peaceable Kingdom was the world’s creatures living harmoniously, as Hicks apparently presumed they could, at least in the New World; for he was a devout Quaker. Mostly medium-sized and made on an easel, sometimes framed with a text, these SIGNATURE paintings were initially gifts for his family and friends, while Hicks earned money mostly from painting decorative images that are not remembered. Nearly two centuries later, his achievement is at once respected and disparaged, as he stands as a precursor to later obsessive painters, such as ON KAWARA.

Hicks, Michael

(1956)

Curious it is that a strong academic scholar of 20th-century American avant-garde music has taught for decades not as an institution customarily hospitable to innovative art but at Brigham Young University in high Utah. His books on Henry Cowell, Bohemian (2003) and Christian Wolff (2012) demonstrate why his deeply researched articles on JOHN CAGE especially should also appear as a book. His Sixties Rock: Garage, Psychedelic and Other Satisfactions (1999) is likewise exemplary scholarship featuring musical analysis. As an LDS member, Hicks also published Mormonism and Music: A History (1989) and The Mormon Tabernacle Choir: A Biography (2015). Additionally a composer of chamber and solo musics, he should not be confused with Michael R. Hicks who writes a sort of science fiction. Among the other professors writing expertly about new music count Kyle Gann (1955) at Bard College (US) and Steven Johnson (1951), Christian Asplund (1964), and Jeremy Grimshaw (1973), all also (surprise?) at BYU.

Higgins, Dick

(15 March 1938–25 October 1998)

As a precocious person of arts, Higgins was producing original adult art while still a teenager, some of which was collected in Selected Early Works 1955–64 (1982). In his mid-twenties, Higgins wrote mature arts criticism and founded a major avant-garde publishing house, SOMETHING E LSE P RESS. Though this work had little academic or commercial success (and typically earned more recognition in Germany and Italy than in his native country), it should not be forgotten.

Even if his abundant output may be conventionally divided into such categories as writing, theater, music, film, criticism, and book publishing, it is best to regard Higgins not as a specialized practitioner of one or another of these arts, but as a true POLYARTIST –a master of several nonadjacent arts, subservient to none. In over forty years, he produced a wealth of work, both large and small, permanent and ephemeral, resonant and trivial –uneven, to be sure, as no two people familiar with his activities agree on which are best. (No one trick pony was he.) In my judgment, his greatest contributions are the critical term INTERMEDIA to describe art that incorporates within itself several traditional arts not normally linked together (as in opera or GESAMTKUNSTWERK) and his book publishing, as his Something Else Press was the most substantial avant-garde publisher ever in America. As COLLAGE was a fertile esthetic idea for the first two-thirds of the 20th century, so Intermedia informed much avant-garde art in the third. (Simply, where visual poetry and book-art are Intermedia, another new epithet, Multimedia, by contrast, has come to describe presentations customarily including electronics.)

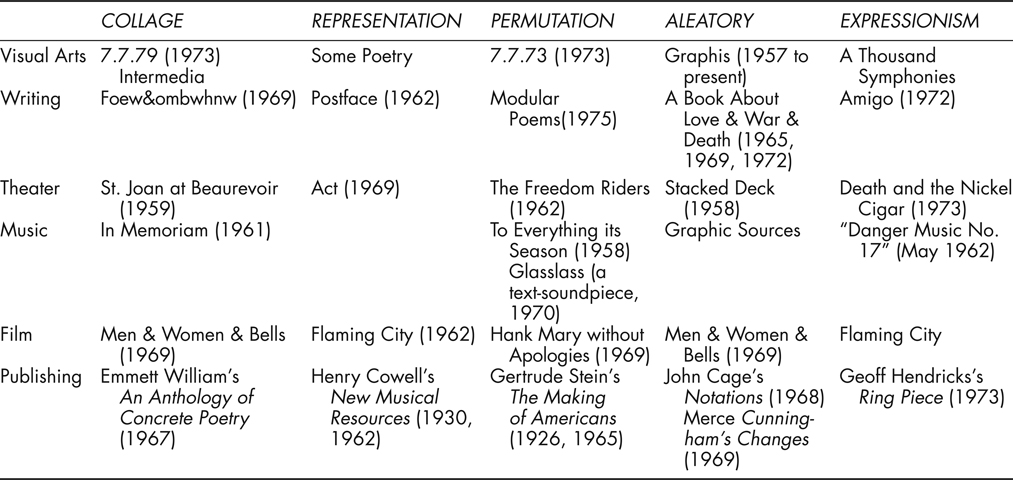

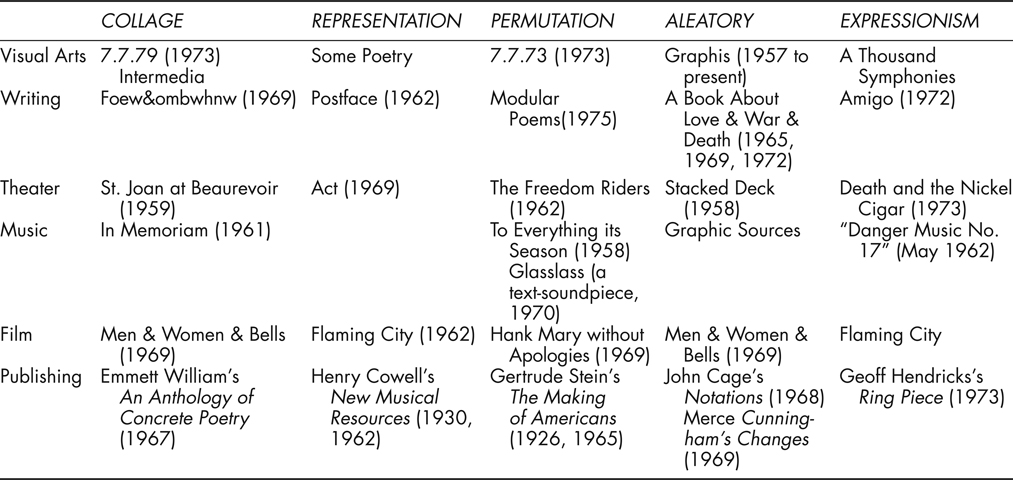

All of his diversity notwithstanding, Higgins reveals five fundamental ways of dealing with the materials of each art he explores. These procedures are COLLAGE, representation, permutation, A LEATORY, and E XPRESSIONISM. In nearly all his works, one or two of these procedures are dominant. Briefly, collage is the juxtaposition of dissimilars; representation is the accurate portrayal of extrinsic reality; permutation is the systematic manipulation of limited materials; alea-tory depends upon chance; and Expressionism reflects personality or personal experience.

Among Higgins’s many works are 7.7.73 (1973), a series of 899 unique prints of various visual images, both abstract and representational, with forms repeated from one print to the next. Amigo (1972) is a book-length poetic memoir of Higgins’s love for a young man. “Danger Music #17 (May 1962)” reads in its entirety: “Scream! Scream! Scream! Scream! Scream! Scream!” Postface (1962) is a percipient and prophetic critical essay about advanced arts in the early 1960s. Saint Joan at Beaurevoir (1959) is a complicated, long scenario that includes such incongruities as Dr. Johnson and Saint Joan appearing on the same stage. Men & Women & Bells (1959) is a short film that incorporates footage made by both his father and his grandfather.

Higgins’s Five Methods

Foew&ombwhnw (1969) –pronounced F, O, E, W, for short –is a book with four vertical columns across every two-page horizontal spread. One column continuously reprints critical essays, a second column his poetry, a third his theatrical scenarios (including Saint Joan at Beaurevoir), a fourth drawings. Though the experience of reading Foew is that of collage, the book as a whole is an appropriate representation of a multifaceted man. Higgins also published a historical study of Pattern Poetry (1987) which is, by common consent, the definitive book on its multicultural subject. He died in action, so to speak, soon after performing to exhaustion his “Danger Music #17,” whose text is entirety: “Scream! Scream! Scream! Scream! Scream! Scream!” In four decades Higgins had realized one of the great artistic lives in America –the rich experience of which book-length biographies are made.

High Red Center

(1962–64)

Formed by Genpei Akasegawa (1937–2014), Jirō Takamatsu (1936–98), and Natsuyuki Nakanishi (1935–2016), they specialized in brazen public demonstrations. Inviting guests to a banquet, 15 August 1962 (the seventeenth anniversary of Japan’s defeat in World War II), the artists ate, drank, danced, and even brushed their teeth –in the summary of the historian Thomas Havens (1939), “using vision to daunt, and thwart unslakable [sic] desire and turning impulses to consume inside out.” In another provocation, Nakanishi, recalls Havens,

rode a train in whiteface and spilled paint on a station platform, then licked and broke open an egg-shaped object containing ordinary items: hair, an old watch, a mirror, a spoon –a satire on the daily hurly-burly faced by harried commuters.

In February 1963, Akasegawa, for instance, showed fake thousand-yen bills etched on one side in a single color. He printed and distributed a flyer on the back of these pieces of paper. The show included a wall hanging on which a large number of these thousand-yen notes were mounted. As well they covered sliding doors and wrapped a briefcase. One result was an indictment for violating the Currency and Securities Counterfeit Control Law. Giving themselves an English moniker was in Japan at the time an outlaw act.

Highwater, Jamake

(14 February 1931–1 June 2001; b. Jackie Marks)

He was a colleague and East Village neighbor whom I knew and personally liked around 1970, because he produced major BOOK-ART, but also curious friend because early I marked him as a chronic fibber. When I first met him, around 1970, he claimed to be younger than I. This I accepted, as he felt contemporaneous, until I discovered in his own house a document with an earlier date (which said 1932, rather than 1931 claimed elsewhere) and an earlier career as a West Coast choreographer. I knew him as J (no period) Marks, which he claimed was Greek, shortened from Markropolous, which seemed credible to me, whose maternal ancestors came from Asia Minor. After all, his skin looked darker than mine. He told me about sisters named just L and M, which was a story unique enough for me to remember a few decades later.

Sometime later, the writer I knew as “J” began to produce books and even television features about Native American art and culture, claiming that his real name at birth was Jamake Highwater and his ancestry as mostly Cherokee. Needless to say, certain Native American critics questioned this. As did in 1986 even the prominent investigative journalist Jack Anderson (1922–2005) in his syndicated newspaper column. More recent researchers have uncovered a birth certificate for one “Jackie Marks” whose father was buried beneath a gravestone with a Star of David. ???

Having already recognized my colleague’s propensity for fibbing, which incidentally also afflicted my otherwise lovely and brilliant partner at the time, I believed the doubters without dismissing his earlier genuine achievements. All the flurry about “identity” that was so serious then seems amusing and dated now, implicitly discounting his real personal achievement, avant-garde in its way, as a masterful re-self-inventor who stuck to his stories even after others dismissed them as fake.

Nonetheless, J Marks produced Rock and Other Four-Letter Words (1970), which probably ranks as the most remarkable example of inventive book-art ever to appear within the restrictive format of a mass paperback sized 7 inches by 4 inches. Given commercial publishers’ unashamed limitations, that is no small achievement. One qualitative measure is, simply, the amount of information and images compressed into its small two-page spreads whose consistently inventive designs scarcely resemble each other. This book appeared after an LP record of the same title (1968), a rich audio pastiche composed with Shipen Lebzelter (1942–86) that was strong enough to be reissued in 2012 on vinyl.

As I recall seeing spreads of Rock’s pages in my colleague’s studio, I thought he did this book by himself; but as nothing else by “Marks” resembles it, perhaps my conclusion is false. Highwater’s quasi-autobiography, Shadow Show (1986), has a reasonable chapter about me who tends to keep friends, rather than dismissing them. As for the possible quality of Jamake’s presentations about Native American culture I’ve no opinion worth sharing. No doubt an informative biography of him will be written.

Hijikata, Tatsumi

(9 March 1928–21 January 1986)

The leading figure and principal founder of the Japanese dance-theater form called B UTOH, Hijikata determined that established dance forms did not satisfy the concerns of his generation or survivors of the shock and horror of Hiroshima. He evolved his Butoh from a wide variety of influences, including his own extensive readings and studies of European avant-garde writers, artists, and performers. His presentation of Kinjiki (Forbidden Colors, 1959), based on a novel by Yukio Mishima (1925–70), at the time one of Japan’s most famous authors, is considered to be the founding event in the development of Butoh. Here a dancer appears to have sexual relations with a chicken and is subjected to sexual advances from another man. Both subject matter and tone shocked the Japanese establishment. In 1960, Hijikata applied the term “ankoku buyo” (darkness dance) to the evolving form only in 1963 to rename it “Butoh” (based on a nearly obsolete term for dance that connotes something more basic than “buyo”). His Rebellion of the Flesh (1968) was another milestone that was also shocking because he killed a chicken as part of the PERFORMANCE. He collaborated with KAZUO O HNO, who was his student (though more than twenty years his senior), and taught and worked with almost all the younger performers who are now continuing the Butoh movement.

—Katy Matheson

Hirsal, Josef

See GRÖGEROVÁ, Bohumila.

Hirsch, Sidney Mttron

(3 January 1884–7 April 1962)

Memoirs and histories of the Southern WASP writers known as The Fugitives (John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, Robert Penn Warren, et al.) scarcely mention the slightly older Jewish literary agent who became in 1923 their first president, who proposed that they publish an eponymous literary magazine (1922–25), in whose sister’s Nashville house the aspiring writers regularly met. Remembered initially as the human model for classic sculptures by both Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) and GERTRUDE VANDERFIL WHITNEY and then a playwright, a fictioner, and an arts critic, Sidney Mttron Hirsch was early in taking an interest in the Kabbalah (where he found his striking middle name), astrology, numerology, Rosicrucianism, and much other radical esoterica.

How much influence Hirsch had upon the subsequently more visible American writers seems unknown and thus worth further research. In a memoir of a gathering by the Southern writer Donald Davidson (1893–1968) is this vivid glimpse:

[Hirsch] picked out some words –most likely a proper name like Odysseus or Hamlet or Parsifal –and then, turning from dictionary to dictionary in various languages, proceeded to unroll a chain of veiled meanings that could be understood only through the system of etymologies to which he had the key. This, he assured us, was the wisdom of the ages –a palimpsest underlying all great poetry, all great art, all religion, in all eras, in all lands. All true poets possessed this wisdom, he told us, solemnly, repeatedly.

Wow. Would that I could have attended such a marvelous private performance. Little is remembered about the last three decades of Hirsch’s life.

Histories (Of Avant-Garde Arts)

(1946)

One quality common to the greatest histories of radical MODERNISM is discussing all the arts together, whether in appreciating a single institution, such as Mary Emma Harris (1943) on The Arts at Black Mountain College or Hans Maria Wingler’s The Bauhaus (1969), or the most innovative work in several arts, as in L. MOHOLY-NAGY’s remarkably percipient Vision in Motion (1946). One critical departure, epitomized by Roger Shattuck in The Banquet Years (1958), is representing the period between 1885 and World War I with four artists working in music composition, painting, theater and fiction, and poetry and criticism. Among the mono-art critical histories of the avant-gardes, few can rival GUILLERMO DE TORRE on literature, PAUL GRIFFITHS on music, or SIEGFRIED GIEDION on architecture, all of whose books remained relevant decades after their original publication. The avant-garde usually dominates in memorable books by discriminating historians, as, by contrast, those favoring traditional work in the 20th century tend to be paltry, if not embarrassing. Q. E. D.

Höch, hannah

(1 November 1889–31 May 1978; b. Anna Therese Johanne H.)

If PAUL CITROEN made the single most classic photomontage and JOHN HEARTFIELD more famous political recompositions, Hoch was the more adventurous, not only in her art but in her life. As early as 1915 she joined both RAOUL HAUSMANN and then BERLIN DADA, soon creating from photo snippets rectangular montages with richly various imagery often personal. In her Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Beer-Belly on the Weimar Republic (1919), often reproduced, she pasted papers with images of people both familiar and unfamiliar, industrial tools, words, letters, and bric-a-brac, all equally present in non-centered space within a frame roughly 5 feet by 3 feet. Similar tastes inform Da-Dandy (1919), which is much smaller at 12 inches by 9½ inches.

Otherwise, Hoch was the only woman artist whom the other prominent Berlin Dadaists, all male, treated as an equal. As Hoch left Hausmann for a nine-year relationship with a Dutch woman before marrying a German man for several years, same-sex couples, switch-hitting (as is said in baseball), and androgyny became recurring subjects in her later photomontages such as Dompteuse (tamer) (1930), which depicts a decidedly female face above crossed muscular hairy arms. Surviving World War II in suburban Berlin, Hoch languished afterwards, unfortunately not surviving long enough to see her work revived and her heroic feminism recognized. A prominent Berlin art prize is named after her; among its recipients, as Berlin is Berlin, are individuals with entries in this book.

Hockney, David

(9 July 1937)

For me he’s always epitomized the artist who knew how to navigate the ART WORLD without ever producing indubitably major work. Curiously, I first heard about him in the spring of 1965, when I met students from London’s ROYAL COLLEGE OF ART (whose magazine Ark was publishing me), because they had already regarded him, then a slightly older recent alumnus, as not necessarily a better painter but as someone far more skilled at getting exhibitions and newspaper coverage than other recent students at England’s most prestigious visual arts college. And indeed he was, relocating to Paris before moving to Los Angeles, establishing close alliances with a prominent curator among other powermen, remaining in America long enough to become an American artist as well as a British, etc. Some identify his photography as superior; another colleague likes his Los Angeles landscapes. (Likewise a daily swimmer, I don’t find his swimming-pool pictures enticing.) As I write this entry, a 2017 retrospective previously at London’s Tate Gallery is moving to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. For a living Anglo-American artist, no doubleplay can be greater.

Hoddis, Jacob Van

(16 May 1887–after 30 April 1942; b. Hans Davidsohn)

One of the more inspired crazy poets, he studied law and published poems before he was in 1912 interned in a BERLIN lunatic asylum. Escaping by jumping out a window in December, he moved to Heidelberg and Paris before returning to Berlin following year. Accepting his schizophrenia, he received private care before being institutionalized in 1933. On 30 April 1942, he was taken away by the Nazis to be killed as both a lunatic and a Jew.

His most memorable poems appeared from 1910 to 1914 in Expressionist magazines. Sixteen of them appeared in a small booklet published as The End of the World (1918). Here is the title poem with an inter-linear English translation:

- Dem Bürger fliegt vom spitzen Kopf der Hut,

- The citizens fly from the tip of the hat head,

- in allen Lüften hallt es wie Geschrei.

- in all airing it echoes like screaming.

- Dachdecker stürzen ab und gehn entzwei

- Roofers crash and go in two

- und an den Küsten –liest man –steigt die Flut.

- and on the coasts –it reads –the tide rises.

- Der Sturm ist da, die wilden Meere hüpfen

- The storm has arrived, the wild seas bounce

- an Land, um dicke Dämme zu zerdrücken.

- on land, to crush big dams.

- Die meisten Menschen haben einen Schnupfen.

- Most people have a cold.

- Die Eisenbahnen fallen von den Brücken.

- The railways are falling from the bridge.

Quickly epitomized as the ultimate urban doomsday poem, his Weltende (1911) was often translated. When Kurt Pinthus placed the Hoddis classic at the beginning of his pioneering anthology of expressionist poetry, Menschheits Dammerung (1920, The Twilight of Mankind), he guaranteed the poet’s immortality. His pseudo-aristocratic invented surname was an anagram of Davidsohn.

Hoffman, Abbie

(30 November 1936–12 April 1989; b. Abbot Howard H.)

His politics aside, Abbie Hoffman was a courageous radical performer whose best shows were always recognized for their theatrical qualities. It was a brilliant move to go to the observation balcony of the New York Stock Exchange and toss handfuls of dollar bills onto the floor below. He led protestors in trying to levitate the Pentagon, which didn’t happen, though this effort too nonetheless made a strong show. Subpoenaed to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee, he wore buckskin pants and a shirt with an American flag. Likewise sensational was his decision, when he didn’t want to be filmed for evening television news, to write the word “Fuck” in lipstick on his forehead.

He could also be a brilliant writer (or talker, whose words were sometimes committed to print), as in this memoir of being Jewish in a traditional Christian prep school in the 1950s:

My favorite hymn was “Onward Christian Soldiers.” You know the part that goes, “With the Cross of Jesus, going as to war.” Jewish kids weren’t supposed to say the name of Christ out loud, so we all had to sing “with the cross of Hum, going as to war.” I did a two-year stretch at Worcester Academy, and by the second year Hum was giving Jesus a run for his money.

When Judge Julius Hoffman fined him five thousand dollars for contempt of court, Abbie replied to another Jew, “That’s a lot of money, Julie. Can you make it three and one-half?”

A LLAN KAPROW appreciates Abbie Hoffman, attuned to avant-garde art, for working the intermedium between radical agitation and stand-up comedy. “It makes no difference whether what Hoffman did is called activism, criticism, pranksterism, self-advertisement, or art. The term intermedia implies fluidity and simultaneity of roles.” So entertaining was Hoffman as a performer that, in comparison, nearly all his radical colleagues seem like earnest schoolteachers.

Realizing that writing could be a form of radical action, he published several books other than memoirs. My own opinion is that Steal This Book (1971) ranks among the most unrestrained incendiary texts ever published in this country. As the commercial publisher commissioning it wanted to censor some of it (under the glib grounds of “editing”), Hoffman self-published it, reportedly selling over 250,000 copies in 1971 alone, thus epitomizing free-enterprise revenge. Like all true classics, Steal was reprinted more than once after his death.

Hofmann, Mark

(7 December 1954)

What HAN VAN MEEGEREN has represented for art forgery, Hoffman stands for literary forgery, both men taking fakery to higher (or lower) levels. However, whereas the Dutchman fabricated paintings allegedly by historic Dutch artists, Mark Hofmann forged documents allegedly made by historic Americans such as George Washington, Paul Revere, Mark Twain, and Abraham Lincoln. Literarily ambitious, he even produced an Emily Dickinson poem previously unknown.

Eventually focusing upon the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, commonly known as Mormon, Hofmann used authentically 19th-century paper in fabricating handwritten pseudo-manuscripts that he successfully sold to Mormon individuals and institutions. Hoffman’s most ingenious move was creating a document purportedly by a historic Mormon previously known only for fragments. This document he placed in the stock of a classy Manhattan antiquariat that sold it to a Mormon institution. Once that forged document was accepted as authentic, Hoffman could produce and sell more documents purportedly written by this long-dead individual.

When his treachery began to unravel, he constructed bombs that killed two people before a third exploded in his own car, injuring him seriously, eventually leading to his arrest and imprisonment not for uncommon forgery but common murder. At the artful forgery of not just historic manuscripts but the œuvre of an historic figure, Hoffman’s achievement has never been duplicated. Were Van Meegeren as fictively imaginative, he would have resurrected some lost Dutch painter with a considerable body of pseudo-authentic work.

Holography

(c. 1947)

A technology new to the 1960s, drawing upon scientific discoveries of the late 1940s, holography superficially resembles photography in representing an image on two-dimensional photoemulsion (film), but it differs in capturing an image in different situations (and thus, at least implicitly, at different times) and then in situating that image in illusory space. That is to say that the principal feature of holography is creating the illusion that things are located spatially where they are not. (A variant, called a multiplex or stereogram, is created by shooting an image with motion-picture film that is then compressed anamorphically into vertical slivers that, once illuminated from below, create within a frame the illusion of an image suspended in space.) Holograms differ from stereoscopic photography and 3-D films in that the former can be viewed without special glasses.

Exploiting a laser split-beam process to register information on a photographic plate, holography is also a far more recalcitrant medium than either photography before it, or video, which arrived around the same time. The fundamental measure of the former’s recalcitrance is this statistic: Whereas there are millions of photographers and millions of video users, nearly all of them amateur, there are only a few dozen holographers, nearly all of them professional.

Incidentally, what they make is a hologram, which is not the same as a “holograph.” That word, at least in English, refers to a document wholly written, usually by hand, by the person who is its author. Among the most distinguished hologram artists are Margaret Benyon (1940–2016), Rudie Berkhout (1946–2008), Arthur David Fonari (1949), Dieter Jung (1941), Sam Moree (1946), Dan Schweitzer (1946–2001), Fred Unterseher (1945), and Doris Vila (1950).

Holzer, Jenny

(29 July 1950)

Holzer is included here only because some readers might expect to find information and insight into her work here; by no known measure is it avant-garde. Her use of language is prosaic, bordering on dull; there is no invention in either syntax or diction. Holzer’s departures, scarcely significant, are to make her words large (without the afterimage resonance gained by, say, ROBERT I NDIANA), and then to use signage technologies that are scarcely unfamiliar. Holzer’s language style descends from slogans; her sentences are designed to impress not for any linguistic excellence but as counter-adages for the cognoscenti whose prejudices, for another measure of kitschiness, are assuaged rather than challenged. By literary measures, “she can’t write” and perhaps doesn’t wish to do so.

Invariably as dumb and unoriginal as possible, her art cons an audience predisposed to the obvious, becoming thereby the litmus test for identifying people who are unsophisticated, which is the inadvertent but beneficial “political” function of her work. If you see a Jenny Holzer in a gallery, in a museum, in a private collection, or illustrated in a magazine, you know a dummy is lurking somewhere. Do not dismiss the social value of such art, for every profession needs an idiot-identifier if it is to remain a profession.

Home, Stewart

(24 March 1962; b. Kevin Llewellyn Callan)

… The epitome of a British activist of alternative letters, also very much a radical South Londoner (which is its DOWNTOWN), Home has engaged his immediate culture widely: playing in a punk band, founding periodicals, editing books, making films, publicizing Parisian Situationism, in addition to publishing fiction both linear and scrambled, fiction criticism, arts history, anarchist critiques, and much else often personal and/or unclassifiable. The apex of Home’s fiction is probably 69 Things to Do with a Dead Princess (2002) which idiosyncratically mixes explicit sex with book reviews and philosophical discussions while playing off his birth name and a recent royal (Royal?) death. As an ironist and a humorist, Home has invented protest movements whose only member was himself. In the 21st century, he has contributed to various blogs.

For his writing, Stewart Home favors smaller obscure publishers, so most of his books are hard to find, even in libraries that should have them, at least until an enlightened publisher rescues them or all become available on his eponymous website. Though Home never earned much money, he’s created much of value both socially and intellectually. If he lives long enough, his name will someday grace the Honors List. About his unique life at least one biography will surely be written.

Home Theater

(1990s)

This new epithet describes the possibility for the homeowner to purchase enough audio and video equipment to simulate the experience of a movie-house. This requires not a monitor, like traditional television, but a screen that receives a projected video image (either from in front or from behind), in addition to several loudspeakers of varying capabilities distributed over the seating area. Designed principally for watching movies, such a system also enhances the sound of compact disks, to the degree that six speakers are better than two. Fans of science fiction movies or movies with many stereophonic effects (such as airplanes swooping across the sound field) are particularly enamored of the sound quality available through having a subwoofer and more speakers spread around the room. My own experience of a large video screen (6 feet at the diagonal, taking three projections from an old Kloss perpendicularly in front of it) is that it works best for sports events and old movies. It is less successful at reproducing television produced in a studio or films produced since the mass dissemination of television, which favor closeups designed eventually to be seen on small screens. As film theaters housed within a “cineplex” become smaller and smaller, the home theater maven will go to the moviehouse not for superior reproduction but only to see new films not yet available via DVD or Internet streaming –or perhaps to make new friends.

Houdini, Harry

(24 March 1874–31 October 1926; b. Erik Weisz)

Commonly acknowledged among the great performers in an era of great American popular PERFORMANCE, he became a master magician particularly renowned for his escapes from seemingly impenetrable constraints. He began modestly as a traveling vaudeville performer doing as many as a dozen shows in a single day. Professionally struggling in America, he went to Europe, much as other major American artists did a century ago, to win fame and fortune previously unavailable at home. During his tours around the world, Houdini escaped from handcuffs, straitjackets, jails, underwater containers, and much else daunting. His stage name remains synonymous with higher conjuring a full century later. Were he still alive today, Houdini would probably have his own theater in LAS VEGAS.

Houédard, Dom Sylvester

(16 February 1924–15 January 1992)

Born in Britain’s Channel Islands, Dom Sylvester, as he was commonly known, became in 1949 a Benedictine monk, thereafter residing in Prinknash Abbey in Gloucester, England. A leading English-language theorist of Concrete Poetry in the 1960s, he published and exhibited elaborate, typewriter-composed visual poems that his colleague EDWIN M ORGAN called typestracts, speaking of them as “ikons for contemplation, topological tantric forms linked to language or ‘poetry’ only by the lingering literary hookup anything typewritten still tends to retain.” Modestly he signed his works only as “dsh,” wholly in lower-case letters. Because Dom Sylvester’s poetry was scattered through numerous chapbooks, among them Kinkon (1965) and Tantric Poems Perhaps (1966), while his religious humility deflected his innate idiosyncrasy, his work has benefitted from posthumous exhibitions.

Houédard published a good deal of criticism, often as eccentric in its typography as his learning, for instance succinctly defining his personal poetic tradition as:

benedictine baroque as contrasted with the Jesuit –& poetmonks in the west [who] have always cultivated what [Cardinal] newman calls “the alliance of Benedict & Virgil,” eg: s-abbo s-adelhard agobard b-alcuin s-adlhelm (the concretist) s-angilbert s-bede s-bertharius (caedmon) s-dunstan (another concretist) flaws fridoard gerbert (sylvester II) heiric hepidamnthenewsallust herimann v-hildebert hincmar b-hrabanusmaurus (concrete).

Houédard also wrote commentaries on the Christian mystic Meister Eckhart and collaborated in editing the Jerusalem Bible (1961).

House of Wax

(1953)

To compete with the increasingly popularity of television, which had by the early 1950s halved the American film-going audience, the Hollywood studios developed several kinds of alternative projection to transcend the TV screen. One was CINERAMA with its three contiguous screens; a second was CINEMASCOPE with its broader image. Another development was 3-D films, as they are called, because, if viewed through appropriate disposable glasses, they do indeed suggest greater depth than normal film. Of the first, House of Wax, whose plot was trivial, I remember best a sequence in which a male character wields a paddle with a ball attached to its base with an elastic band. As he bounced the ball directly in front of him toward the camera, it seemed to emerge from the screen to various spots around me, intimidating me with its illusion of dimensionality. House of Wax was also the first Hollywood film to offer stereophonic sound that was then likewise unavailable on television. Hollywood produced and/or distributed many later films that could be viewed with 3-D glasses; but if any of them had a scene as strong as that bouncing ball, I don’t remember it.

Howe, Anthony

(1956)

The distinctive mark of his kinetic sculptures is that, physically huge, they are designed to be moved by wind that customarily makes them produce roughly kaleidoscopic imagery. Unlike kinetic sculptures in the tradition of ALEXANDER CALDER, POL BURY, and GEORGE RICKEY, which are designed to move delicately, Howe’s become propulsive, its parts moving rapidly in a kind of militaristic grandeur. Necessarily taller and larger –as much as 40 feet in diameter –they become quite imposingly visible in public. My associate Shoshana E. Stone describes Lucea (2016) in Dallas, TX, as appearing to be “symbolically broadcasting an important, inspiring message from another universe that awaits our response.” Perhaps the most prominent was Howe’s cauldron created for the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro.

Hpschd

(1969)

One of JOHN C AGE’s most spectacular pieces, created in collaboration with the pioneering computer composer Lejaren Hiller (1924–94), HPSCHD was premiered at Assembly Hall, essentially a humongous basketball arena at the University of lllinois’s Urbana campus, 16 May 1969, for five hours. The venue’s name is appropriate, because Cage assembled an immense amount of visual and acoustic materials. On the outside walls were an endless number of slides projected by fifty-two projectors. In the middle of the circular sports arena were suspended several parallel sheets of Visquine, each 100 by 40 feet, and from both sides were projected numerous films and slides whose collaged imagery passed through several sheets. Running around a circular ceiling rim was a continuous 340-foot screen on which appeared a variety of smaller images, both representational and abstract. Beams of light spun around the upper reaches, both rearticulating the concrete supports and hitting mirrored balls that reflected dots of light in all directions. Lights shining directly down upon the asphalt floor also changed color from time to time. Complementing the abundance of images was a sea of sounds that had no distinct relation to one another –an atonal and astructural chaos so continuously in flux that one could hear nothing more specific than a few seconds of repetition. Most of this came from fifty-two tape recorders, each playing a computer-generated tape composed to a different scale, divided at every integer between five and fifty-six tones to an octave. Fading in and out through the mix were snatches of harpsichord music that sounded more like Mozart than anything else. These sounds came from seven harpsichordists on platforms raised above the floor in the center of Assembly Hall. Around these islands were flowing several thousand people. HPSCHD was an incomparably abundant visual/aural uninflected E NVIRONMENT, really the most extravagant of its kind ever presented. A few years later, Cage mounted a “chamber version,” with far fewer resources, at New York’s Brooklyn Academy of Music. Literally abridged, this slighter HPSCHD did not have a comparable impact.

Huelsenbeck, Richard

(23 April 1892–20 April 1974; b. Carl Wilhelm Richard Hülsenbeck)

Incidentally residing in Zurich in 1916, this young German doctor participated in the beginnings of D ADA, which he continued to support in BERLIN in 1918. Better self-organized than his artist colleagues, Huelsenbeck wrote the first history of Dada in 1920–21 and edited the Dada Almanach (1920), an anthology so well selected it was reissued in the original German by SOMETHING E LSE PRESS in 1966. After years as a ship’s doctor cruising the world, Huelsenbeck landed in 1936 in New York, where he became a psychiatrist (taking the name Charles R. Hulbeck) and, after World War II, was the only first-rank participant in Dada based in New York. His 1916 poem “End of the World” resembles GUILLAUME A POLLINAIRE’s “Zone” in its disconnected lines, universal scope, and lack of punctuation.

Huelsenbeck’s Memoirs of a Dada Drummer (1969) is very candid, not only about his colleagues but about his success as a New York shrink who, as he boasts, maintained an office at 88 Central Park West and sent his children to the best schools. “As a doctor I was a success and as a Dadaist (the thing closest to my heart) I was a failure,” he reportedly declared. Given the scant rewards for avant-garde art in New York, it is always gratifying to learn that its creators can find other vehicles of patronage.

Hughes, Patrick

(20 October 1939)