J

Jackson, Martha K.

(1907–69)

Prior to LEO CASTELLI, only a few years her junior, she was during their time together the most successful sophisticated dealer in avant-garde American art. Born in Buffalo, she studied art history at John Hopkins before, divorced, relocating to Manhattan after World War II, opening in 1952 an eponymous gallery on East 66th Street. Initially a collector with a modest trust fund, she regularly visited artists’studios customarily purchasing two works –one to keep, the other to sell. Later she moved to 57th Street, which became for two decades the principal venue for galleries exhibiting new art and incidentally sponsoring openings where aspiring artists could expect to meet each other. Much was discovered in her premises; much new learned. (Once there, I remember.)

Among the artists exhibiting in her spaces were WILLEM DE KOONING, JOHN CHAMBERLAIN, ALLAN KAPROW, CHRISTO, LOUISE NEVELSON, MORRIS LOUIS (for his sole one-man show in his lifetime), GUTAI (in 1956 & 1958), and CLAES OLDENBURG. (Her 1966 exhibition of the last artist was particularly successful in establishing his preeminence.) Eclectic in her tastes, Jackson is credited with exhibiting OP ART before the successful MoMA show. In 1969, just as the retailing of new art moved DOWNTOWN, she closed her gallery, depositing her archives in Buffalo. In addition to paper documents, these include over 120,000 photographs of every work ever exhibited and gallery installations. Martha Jackson knew that her gallery was contributing to Art History. As happens too often in art, the son inheriting her gallery (who grew up in the apartment above it, later working as his mother’s assistant), renaming it after himself (David Anderson), couldn’t function as well. Just as the sons of great baseball players rarely duplicate their father’s success and the children of great artists likewise thrive, so is the business of selling new art ferociously selectively competitive.

Jakobson, Roman

See FORMALISTS, RUSSIAN.

Janco, Marcel

(24 May 1895–21 April 1984)

Born Jewish in Bucharest, Janco happened to be studying architecture and painting in Zurich in 1915, at the beginnings of the DADA movement, joining HUGO B ALL, RICHARD H UELSENBECK, and his fellow Rumanian, TRISTAN T ZARA. A few years earlier he had cofounded a literary journal, Simbolul (The Symbol) with Tzara, its title reflecting an esthetic value popular in European literature at the time. While active in Zurich D ADA, Janco made paintings and reliefs that are still regarded as his strongest visual art, as well as neo-African masks and memorable woodcut illustrations to a Tzara poem. He is honored primarily for his 1916 painting of the CABARET V OLTAIRE, the initial Dada venue. For the exhibition he designed a striking woodblock announcement with only white letters on a black field.

Moving to Paris in 1919, Janco soon broke with Tzara and returned to Rumania, where he founded Contimporanul (1922–40) and worked as an architect. Meanwhile, nearly all of Janco’s Dada art disappeared, including the Café Voltaire painting mentioned above, which was last exhibited in his native Bucharest, to be remembered only in photographs or, less fortunately, exhibition catalogues and lists. By 1941 Janco was safely in Palestine, where he remained until his death, in a country sadly so inhospitable to avant-garde art (in contrast to avant-garde science, say) that its more remarkable creative personalities necessarily make their careers abroad, much as comparable Americans did in the 19th century.

Janecek, Gerald

(15 August 1945)

One of the few full-time academics to write intelligently on avant-garde subjects, he authored The Look of Russian Literature (1984), which documents the development of visual devices mostly in FUTURIST writing of 1900–30. In contrast to previous commentators, such as Vladimir Markov (in Russian Futurism: A History, 1968), who tended to favor the poetry of VELIMIR K HLEBNIKOV, Janecek concentrates upon the most radical figure, ALEKSEI K RUCHONYKH, finding more sense than anyone else previously unearthed in his innovations and extravagances. What makes Janecek’s avant-garde criticism special is his willingness to understand the most extreme: not only the most advanced individual in a group but his or her furthest departures. His principal sequel deals thoroughly with Z AUM, or “transrational language,” which Markov before him dubbed “the most extreme of all Futurist achievements.”

Jargon

In critical writing, the function of jargon is not to illuminate but to suggest that its author is “verbally correct,” which is a higher (or lower) semblance of POLITICALLY CORRECT. So, should you come across a piece of criticism filled with imposing terms (such as “ambiguity,” “tension,” and “metonymy” in days gone by; “dialectical,” “signifier,” “disruption,” “confrontation,” “contradiction,” “deconstruction,” “differance” [sic], “logocentrism,” “asymptotic,” “indexical,” “decentering,” etc., recently; Lord Knows What, nowadays), to all appearances used in unfathomable ways, do not worry and, most of all, don’t be intimidated (unless you’re a student or an untenured professor, whose function in the academic hierarchy is to be predisposed to intimidation). You’re not supposed to understand anything, but merely to be impressed by the author’s modish choice of lingo, much as, in other contexts, you might be awed by his or her choice of dress, shoes, car, or something else superficial.

It was the caustic American sociologist Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929) who pointed out more than a century ago that inefficient expression is meant to reflect

the industrial exemption of the speaker. The advantage of the accredited locutions lies in their reputability; they are reputable because they are cumbrous and out of date, and therefore argue waste of time and exemption from the use and the need of direct and forcible speech.

That is to say, you must be economically comfortable to talk that way and, by doing so, are implicitly announcing that you are. The reason why such jargon amuses common people is that they know instantly, as a measure of their lesser economic class, what its real purpose is.

Jarry, Alfred

(8 September 1873–1 November 1907)

An eccentric’s eccentric, who lived modestly and needed collegial support to make his works known, Jarry wrote plays and fiction so different from the late Victorian conventions that they are commonly regarded as having anticipated S URREALISM, D ADA, the THEATER OF THE A BSURD, and much else, which is to say that Jarry was a slugger in spite of himself. His play Ubu Roi (King Ubu, 1896) opens with the word Merdre, which is customarily translated as “Shittr,” proclaiming from the start its ridicule of bourgeois false propriety. Furthermore, the freewheeling movement from line to line, and scene to scene, makes it different from any plays written before.

Yet more innovative, to my mind, are Jarry’s fictions, such as Gestes et Opinions du Dr Faustroll, Pataphysicien (1911), and Le Surmâle (The Supermale, 1902), in which ridiculousness is raised to a higher level. The former begins as a satire on Lawrence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1767), if that is possible, but it ends in the modern world with pseudo-mathematics in an extraordinary chapter “Concerning the Surface of God,” which concludes with this monumental IRONY: “GOD IS THE TANGENTIAL POINT BETWEEN ZERO AND INFINITY.”

Though Jarry was a limited writer, the image of the man and his work had a great influence upon his avant-garde betters; in this respect, he resembles his near-contemporary compatriot, RAYMOND R OUSSEL, and his successor, ANTONIN A RTAUD. (Another useful divide within avant-garde consciousness is separating those who treasure Jarry from those who worship Artaud and thus those valuing mad invention over inventive madness.) After initiating a college du ‘PATAPHYSIQUE, Jarry died young of tubercular meningitis aggravated by alcoholism, which was in its time no more avant-garde, alas, than drug abuse was later.

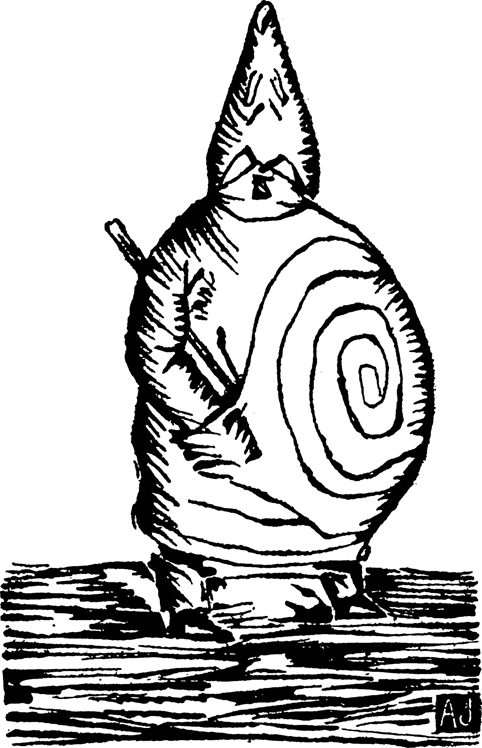

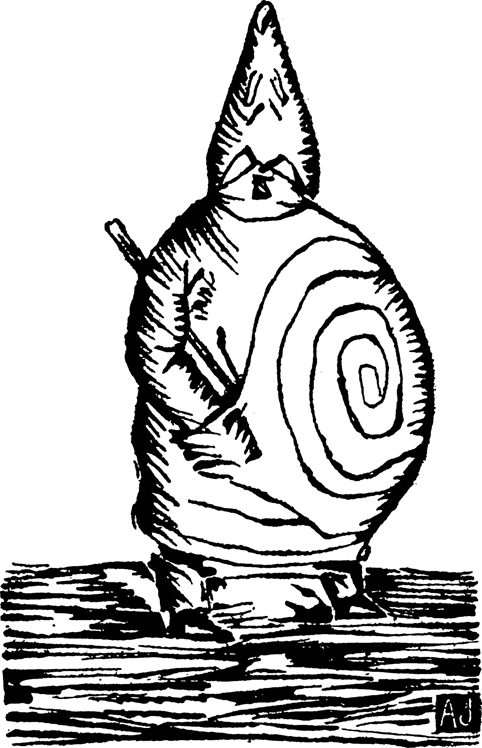

Figure 8 Alfred Jarry’s woodcut portrait of Master Ubu, 1896.

Jazz

(c. 1885)

Arising from obscure origins in the American South, this indigenous music first became prominent in New Orleans at the beginning of the 20th century. While reflecting African and African-American concepts of alternative rhythm and group participation, early jazz initially followed black gospel music in observing European harmonies abetted by rhythmic deviance. Nonetheless, other musical strategies seem peculiar to jazz in its many forms: melodic improvisation within a predetermined harmonic range; continuous harmonies either within a solo instrument or a backup band; and certain kinds of instrumentation and thus timbre and intonation. Even when adopted by musicians other than African-Americans, such as BIX B EIDERBECKE, a master improvising cornetist from Iowa, or Jewish Klezmer musicians, the result is called jazzy –or, in the Klezmer example, “Jewish jazz.” Though many prominent jazz musicians had compositional careers, jazz has remained essentially a performer’s music.

Avant-garde jazz is the fringe that was initially unacceptable because of formal deviations, beginning historically with LOUIS A RMSTRONG’s transcending the piano-based ragtime predominant between 1900 and 1920 by featuring the trumpet as a solo instrument. This departure created the foundation for the “big bands” of the 1930s that featured brass instruments customarily played in harmonic unison. The principal alternative to this style came in the 1940s with the dissonance cultivated by CHARLIE P ARKER in smaller bands. Behind him came in the next decades ORNETTE C OLEMAN and ALBERT A YLER, among others, who eschewed any metronomic beat while often playing as rapidly as possible.

The development of jazz is [to Richard Carlin] a paradigm for American avant-garde success. Instead of moving linearly from folk blues to Dixieland jazz through big band jazz to BEBOP and free jazz to jazz/ rock fusion to new acoustic jazz (in emulation of a European model of avant-garde development), jazz both moves forward and looks backwards. Although the heyday of New Orleans jazz was the 1920s, New Orleans jazz continues to be played today, both by musicians raised in this style and by others who emulate it. In this sense, each new style does not replace the old ways, but rather complements them. [RK disagrees with this RC formulation.]

From the beginning of the 1920s, classically trained composers could hardly resist the influence of jazz, as many of them incorporated one or another jazz device (or, sometimes, a live jazz musician) into their own works. Though such fusions are sometimes hailed for representing a “third stream” between classical music and jazz, that epithet has never had much acceptance with either the jazz public or that devoted to modern-ist classical music. The real influence of jazz on classical avant-garde music lies in the acceptance of kinds of rhythms, beginning with syncopation, indigenous to North America.

One recent myth that must be dispelled is that jazz is an African-American monopoly. Elsewhere in this book is an entry on BIX BIEDERBECKE, a Caucasian whose improvisations represented jazz at its best. NICOLAS SLONIMSKY, from the perspective of classical music, thinks that whites in the 1920s

developed a modern type of jazz designed for concert performance. Among them were Benny Goodman, Woody Herman, Guy Lombardo, and Paul Whiteman. The most important contribution to concert jazz was made by GEORGE GERSHWIN, whose Rhapsody in Blue became a modern classic.

Few jazz keyboardists have been as brilliant as George Shearing (1919–2011), who was born blind in the Battersea section of London. The first great jazz guitar-ist was a Belgian gypsy named Django Reinhardt (1910–53).

A subsidiary effect of jazz’s success was new kinds of dancing, not only between couples in social situations but on stages, beginning with percussive tap dancing that complements jazz to the same degree that classical music complements ballet. Within this general rubric of jazz dance are a wide variety of alternatives with unique names, such as Black Bottom, Shimmy, Charleston, Cakewalk, Strut Step, Hucklebuck, Mashed Potato, about which an encyclopedia could no doubt be written. Marshall and Jean Steams’ Jazz Dance (1968) includes graphic notations documenting how various parts of the body should be positioned for each dance, in addition to a list of films and kinescopes dating back to the end of the 19th century.

One interesting measure of jazz’s cultural acceptance is that, since 1950, most purportedly comprehensive histories of American music acknowledge jazz.

—with Richard Carlin

Jean, Marcel

(16 December 1900–4 December 1993)

Every avant-garde art group needs an associate who can write; better, someone who can write well; best, who can write irreplaceable “insider” histories. For SURREALISM that person was Marcel Jean. For his own art, one specialty was decalcomania, which for his colleagues meant not transferring images from paper onto glass or porcelain but pressing ink between sheets of paper and then separating the papers to discover a surprise that may or may not be accepted, to which some ink lines might later be added.

In addition to writing Histoire De La Peinture Surrealiste (1959; The History of Surrealist Painting, 1967), Marcel Jean edited the Autobiographie du surreálisme (1968; Autobiography of Surrealism, 1980), which is a rich chronological documentary history. Jean also traveled widely, mostly lecturing about Surrealism. Around the time of the former book’s publication, he sat beside me for a New York City radio program, speaking English as fluently as mine. For the second big book, which was apparently commissioned initially in the US, the English commentary was mostly his own. Best at his particular role he probably was. (Had I known more about his past, I would have asked about the principal mystery of his biography: How did he manage to survive World War II working in a factory in Hungary?) For his enthusiasms Marcel Jean was the complimentary antipode to his Parisian contemporary MICHEL SEUPHOR, who comparably chronicled CONSTRUCTIVISM and ABSTRACTION.

Jewish Art

As an artist and writer born Jewish, I feel obliged to write an entry that, alas, isn’t as rich as I’d wish it to be. Given the proscriptions against graven images, Jewish art, avant-garde Jewish art truest to Judaism, should be nonrepresentational –certainly devoid of people, if not nature as well. Only with other-worldly forms can other-worldly experience be portrayed. With this principle in mind, consider that the exemplary master Jewish modern artists are not MARC CHAGAL and AMADEO MODIGLIANI, for familiar examples, but BARNETT NEWMAN, LOUISE NEVELSON, and MARK DI SUVERO, none of whom have worked much with Jewish imagery or themes. (Indeed, perhaps the most notable Newman work portrays abstractly the Stations of the Cross.)

For music, few works compare with STEVE REICH’s Tehillim (1981) and Alvin Curran’s Crystal Psalms (1988), both of which incidentally began as commissions from German radio. The greatest film by Jerry Lewis (1926–2107), a truly gifted comedian, may (or may not) have been his most Jewish film about a clown in a Nazi concentration camp, The Day the Clown Died (1972), which he withdrew from public circulation soon after an initial screening. On the other hand, most of the greatest innovators in the art of printed comics were Jewish.

Modern synagogue architecture I find disappointing, particularly in America, where no Jewish church known to me reaches the level of those, say, in Rome or Florence, Italy. On the other hand, at placing abstract sculptures in synagogues and other Jewish institutions, few succeed as well as Ibram Lassaw (1913–2003, b., Egypt) and my sometime SOHO neighbor Oded Halahmy (1938, b. Iraq), the latter’s penchant for irrelevantly kitschy descriptive titles notwithstanding.

Certain questions remain in this admittedly open-ended entry: For instance, how Jewish is the art of the Rumanian DADA artists TRISTAN TZARA and MARCEL JANCO? Does the drive toward abstraction in Gertrude Stein’s prose reflect her Jewish birth? And so on?

Whoever prepares the next edition of this Dictionary might elaborate or discard.

Johns, Jasper

(15 May 1930)

Though he was initially paired with his friend ROBERT R AUSCHENBERG, who was five years his senior, Johns is a different sort of artist, concerned less with exploring unfamiliar materials than with creating objects that pose esthetic questions. In looking at his early and prototypical Target with Four Faces (1955), one cannot help but ask: Is this a replica of a target? A collection of concentric circles? Or something else? What relationship do those four sculpted bottoms of heads (noses and mouths, to be precise) have to the two-dimensional picture? Why is the target-image represented so realistically and yet the heads so sur-realistically? Is there some symbolism here, or do all meanings exist within the picture? “I thought he was doing three things,” JOHN CAGE once wrote, “five things he was doing escaped my notice.” By painting a realistic image without a background, Johns followed JACKSON P OLLOCK in abolishing the discrepancy between image and field that had been a core of traditional representational art, again raising the question of whether the target-image was a mechanical copy of the original target, or a nonrepresentational design (and what in this context would be the difference anyway?). Later Johns works develop this love of images and objects unfamiliar to painting, as well as displaying his taste for ambiguity, puzzle, and enigma. Given such a high level of exploratory richness, it is not surprising that the first major critic of his work should have been LEO STEINBERG, an art history professor whose forte was the exhaustive examination of significances available within a single picture. Johns’s work is generating a secondary literature approaching in size that devoted to MARCEL D UCHAMP, so that even catalogues accompanying his exhibitions physically resemble coffee-table books.

Johnson, B. S.

(5 February 1933–13 November 1973; b. Bryan Stanley J.)

The most experimental British novelist of his generation, Johnson began with Traveling People (1963), in which narrative gives way to impressionistic stream-of-consciousness, and Albert Angelo (1964), which, telling of an impecunious architect working as a substitute teacher, includes a section where spoken thoughts on the right side of the page become a counterpoint to the monologue on the left-hand side. Pages 149–53 of the latter book contain a hole that is purportedly caused by the knife that killed Christopher Marlowe (how British!). “Why do the vast majority (it must be over 95 per cent at a reasonable guess) of novelists writing now still tell stories,” Johnson asked provocatively in Books and Bookmen (1970), “still write as though Ulysses (let alone The Unnameable) had never happened?”

As Johnson practiced what he preached for fiction in the late 20th century, his greatest departure was The Unfortunates (1967), which came in a box whose opening and closing chapters were fixed, while the remaining twenty-five were loose, to be read and reread in any order, purportedly reproducing the jumble in his mind on a particular Saturday afternoon when he is assigned to cover a football (soccer) match for a Sunday paper. (As this was a job that Johnson actually worked when I first met him in 1965, the inspiration was autobiographical.)

Johnson published poems and stories, in addition to making a film that won several prizes, You’re Human Like the Rest of Them (1968). Of the ten books he published before his suicide, only one, his first collection of poems, was republished in America in his lifetime.

Johnson, Ray

(16 October 1927–13 January 1995)

A lightweight whom some regarded as a light-heavyweight, he produced COLLAGE too late to be innovative and too trivial to be monumental. Some of these works used words along with images in witty ways, at times with disarming simplicity. As a pioneer at MAIL ART, he publicized the mythical New York Correspondance [sic] School, its title satirizing the 1950s art-sales epithet of “New York School.” Persisting with his unique integrity for decades, Ray Johnson became an artist whose work was collected and eventually exhibited in galleries, not to mention in a solo museum show.

Four biographical facts: As an alumnus of BLACK MOUNTAIN COLLEGE, he befriended other artists easily, perhaps because few, if anyone, regarded him as threatening. He acquired well before his death a heavyweight art dealer. He had a long sub rosa affair with a sculptor publicly known as securely married with children. Since the Johnson I saw now and then had a sunny disposition (unlike B. S. JOHNSON, whom I also knew slightly), may I assume that he calculated that his jumping off a bridge in Eastern Long Island in his late sixties would be remembered as his final PERFORMANCE, as indeed it is.

Johnson, Samuel

(18 September 1709–13 December 1784)

Aside from other contributions he made to English Literature, particularly as an exemplary essayist, this Johnson became the first master of the Art of the Entry, which is his case was stylish definitions of English words in the form of a Dictionary. Given the constraint of very few words, an entry necessarily becomes a platform for aphoristic writing that at its best lightly reflects great learning as it incorporates economy and wit. Ideally, a good entry should be remembered, if not precisely, at least credibly; if not as a whole, at least in part. Among this Johnson’s classics are:

- Rant: High sounding language unsupported by dignity of thought.

- Network: Any thing reticulated or decussated, at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections.

- Rust: The red desquamation of old iron.

- Grubstreet: Originally the name of a street in Moorfields in London, much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems; whence any mean production is called grubstreet.

More than any other dictionary known to me Johnson’s contains rich asides. It also inspires the reader not to read continuously but to flip pages, both backwards and forwards, before putting the book down. It is commonly considered the greatest work of literature customarily kept in the “reference” section of a library.

Unfortunate it is that most later dictionaries, at least in English, are written by committees and thus devoid of style. Nonetheless, among the later masters of this Entry Art are NICOLAS SLONIMSKY, AMBROSE BIERCE, and JOHN ROBERT COLOMBO whose books have likewise been produced by one learned and witty writer.

Figure 9

Sara East Johnson “Utopia” from the A Goddessey, 2017, featuring dancers Efemina Alibo, Hilary Melcher Chapman, and Molly Chanoff (left to right).

Johnson, Sarah East

(18 September 1967)

A short and broadly built woman initially trained in dance, Sarah East Johnson has spoken of her early wish to “perform with MERCE C UNNINGHAM, ELIZABETH S TREB, and Circus Oz.” Instead, she made PERFORMANCE that reflects not only her remarkably powerful female body but her diverse mentors: Cunningham for nonrepresentational movement, Streb for athleticism, and the circus for her use of trapeze swings and other props. Her dancers frequently perform like acrobats while hanging onto crossbars, suspended ropes, or one another, but the pacing of Johnson’s work especially honors her origins in modern dance. Some of her innovations come from slowing down circus-like movements, better to display their choreographic beauty; and in this respect, in particular, she differs from Streb, who favors speed. “Dance is my world,” she once told a reporter. “I just use a different vocabulary than most choreographers.”

My single favorite Johnson move, “Hoop Diving,” involves two thick-sided hoops, stacked one atop the other, so that her dancers approaching them perpendicularly can decide to dive through either the lower or upper one, in either case the prop forcing them to move their bodies in choreographically remarkable ways. Another masterpiece is the magisterial duet Adagaio with Johnson supporting a slighter woman dancer on her shoulders, thighs, hands, and back, much as male dancers traditionally supported women, but here more acrobatically. Because her performers are nearly always women, one Johnson theme is the potentialities of female athletic strength.

Jolas, Eugene

(26 October 1894–26 May 1952)

Born in New Jersey, Jolas grew up in Lorraine, France (near Germany), before returning to the United States in 1911. Back in Paris in the 1920s, he worked for newspapers and then edited TRANSITION, which was the most distinguished avant-garde magazine of its time. It published not only episodes from James Joyce’s FINNEGANS WAKE among other literature that was avant-garde at the time, but illustrations of advanced paintings and even, in a departure rarely imitated, scores by comparably vanguard composers.

Consider that in the history of American avant-garde publishing Jolas’s TRANSITION represents one line while NEW DIRECTIONS represents another with scarcely any overlap. Jolas favored the more eccentric writers such as BOB BROWN, SAMUEL BECKETT, and GERTRUDE STEIN, as well as more eccentric works such as FINNEGANS WAKE while New Directions learned from KENNETH REXROTH, WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS, Delmore Schwartz (1913–1966), and somewhat less eccentric European writers such as Hermann Hesse (1877–1962) and DYLAN THOMAS. Once TRANSITION ceased publishing, New Directions appeared to represent the vanguard, at the expense of neglect of work further out.

The most distinctive Jolas poems draw upon his multilingual background, as some like “Mountain Words” broach self-invented language:

- mira ool dara frim

- oasta grala drima

- os tristomeen.

Others combine German, French, and English, such as this opening of “Weltangst en Chevauchant une Frontiere,” a polylingual prose poem:

The earth is troubled es geistert dans les cavernes her disalogues der draklings lopent through the griefhours it is so icy in the eyes in the world of and streets are tired with waiting for kinderlieder et hymns

singmourn the legends le matin is droguegrey die hirne hungern nach paradis the lonely hunting horns are tenebrating in the miserere of rooks dans la chronique de forces dans le deesert évanoui

all reflecting the sensibility of a man who said he dreamt in three languages.

Books of Jolas’s poetry have long been out of print, and his Man from Babel (1998) draws from autobiographical manuscripts drafted a half-century before. His daughter, Betsy J. (1926), is a distinguished American composer who, though she went to college in America, has resided mostly in France.

Jones, Bill T.

(15 February 1952; b. William Tass J.)

As a former track runner who became a dancer, Jones began as a spectacular performer who soon became his own choreographer, much as MERCE CUNNINGHAM did decades before him. Hailed as well as blamed for publicizing his race (black) and physical disability (HIV-positive), Jones should really be credited with a radical departure in choreographic composition. Though Jones himself was thin and athletic, his initial partner Arnie Zane (1948–88) was short and considerably less athletic. Objecting to “things that separate people,” Jones has included in his performance company dancers who were old as well as young, fat as well as thin, at one point even requiring them all to bare themselves on stage. It was not only an unprecedented vision of theatrical dance but a statement about humanity realized intelligently through performance.

As he was diagnosed HIV-positive in 1985 and Zane died from AIDS-induced complications a few years later, Jones began in 1992 to conduct a nationwide series of “survival workshops” for people who had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, cancer, AIDS, and other serious illnesses. Out of these workshops came the performance piece Still/Here (1994) that explores the experience of living and surviving under threat of death. This work prompted Arlene Croce (1934), then the veteran dance critic for The New Yorker, to write that she would not review it because it was “beyond criticism” as “victim art.”

What could have been discussed, what should be remembered, was the composition of his company and thus Jones’s courageous, if exploitative, use of physiques not previously seen in formal performance.

The other remarkable masterpiece in his history are the surviving pictures of his nude body painted with white hieroglyphs by Keith Haring (1958–90).

Jones, Chuck

(21 September 1912–22 February 2002; b. Charles M. J.)

Coming of age in Los Angeles, just as the film industry was rapidly burgeoning, he found work not in the features but in shorter films that shot not live performers but hand-made drawings –actually sequences of drawings –and were thus called “cartoons.” Thanks to support from Warner Brothers, whose bosses wanted shorter films to precede the feature that attracted most filmgoers (some of whom might be arriving late), Jones and his colleagues worked in a corporate outpost where, under-supervised (and under-funded), they were able to make all sorts of remarkable departures, such as the discovery of anthropomorphic animals who could move through the world as people could not. Customarily only several minutes in length, these films also proceed with a speed different from longer Hollywood films, which often put me to sleep.

Prolific and often profound, Jones directed Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, among other popular series; he created a character called the Roadrunner. He made “public service” animations during World War II and afterwards. Whereas most of his 300 cartoons were acceptable for modest purposes, he deserves credit for some of the most brilliant animations of all: Duck Amuck (1953), where the protagonist Daffy Duck must frantically improvise as everything around him rapidly changes in less than seven minutes; and What’s Opera, Doc (1957), which compresses RICHARD WAGNER’s Ring Cycle likewise into a single 35 mm reel less than seven minutes long. In both critical histories of the cartoons genre, these two are counted among the masterpieces.

The great tragedy of Jones’s artistic life was that Warner Brothers shut down animation production in 1962, when he was barely 50 years old. He formed his own company as well as working for other Hollywood studios in the years immediately afterwards. Though always respected, he never again produced work as brilliant as before. For his last years Jones oversaw packages reissuing his greatest works, which are still appreciated, especially in contrast to more recent computer-generated animations that seem visually klunky in comparison. He spoke often and intelligently about his career at venues around the world. Indicatively, the most thoughtful critical appreciation of Jones was written by HUGH KENNER, a literature professor otherwise known for his books about the great modern writers.

I think of Chuck and SPIKE, both Jones, born only several months apart, both from Los Angeles, to epitomize the Angelino imagination at its avant-garde best.

Jones, Spike

(14 December 1911–1 May 1965; b. Lindley Armstrong J.)

One of the greatest comic musical performers ever, a contemporary of CHUCK JONES, both born around Los Angeles within a single year apart, Spike Jones gathered in the early 1940s a group of musicians whom he called the City Slickers, who were willing to perform his extravagant comedy. Their first greater success came with a 78 rpm. recording of “Das Fuhrer’s Face” (1942) in which the semblance of a Teutonic oom-pah band regularly screams “Sieg Hiel” followed by the sound of flatulence to various lyrics deprecating Adolf Hitler. (The real Führer reportedly so hated this record that he tried to destroy every copy he could.)

Over the next dozen years the City Slickers recorded prolifically and toured widely with songs and comic arrangements that were both popular and musically sophisticated. Often they began with a song or theme already popular: “Holiday for Strings,” “Hawaiian War Chant,” “You Always Hurt the One You Love.” More memorable now probably are the group’s take-offs from more classical music, such as Franz Liszt’s Liebestgräume, which they played as fast as they could with unusual instruments; likewise Gioacchino Rossini’s William Tell Overture, played with kitchen implements. As true classics, these musical (re)arrangements remain hilarious decades later.

‘Tis said that Spike’s imagination got lost in the late 1950s wake of early rock music, which he reportedly judged already ridiculous (and thus unavailable for parody), and then the decline in his personal health exacerbated by heavy cigarette smoking. Visibly hyper-nervous, he ostentatiously performed with chewing gum as a kind of SIGNATURE movement. He died too young.

Among the later major musical comedians reflecting his influence count Raymond Scott (1908–94), Allan Sherman (1924–73), Gerard Hoffnung (1925–59, the sole Brit here), P.D.Q. BACH, FRANK ZAPPA, and “Weird Al” Yankovic (1959).

Someday an appreciative book should be written about the two Jones boys, Chuck and Spike, perhaps along with FRANK ZAPPA, as epitomizing a rich strain of Angelino art.

Joplin, Scott

(24 November 1868–1 April 1917)

An itinerant Midwestern pianist, Joplin is generally credited with composing the first popular piano piece to sell a million copies of sheet music, “Maple Leaf Rag” (1899). Although the term “ragtime” was meant to be semi-derogatory, Joplin’s piano pieces were as classically rigorous as Chopin’s études, with four parts, composed AA-BB-AA-CC (trio)-DD. Joplin’s music also incorporated dissonant harmonies, intuitively expanding the musical idioms of popular composition; his “Stop Time Rag” was the first sheet music to include markings for foot-tapping.

One misfortune of Joplin’s life is that, not unlike GEORGE GERSHWIN, after him, Joplin thought himself worthy of more ambitious music, composing a ballet based on ragtime, and then a full-scale opera, Treemonisha (1911), which everyone wishes were better than it is. He died just short of 50, a full half-century before his music was revived, first in brilliant records in the early 1970s by the conductor-pianist-musicologist-arranger Joshua Rifkin (1944), then in the popular film The Sting (1974).

—with Richard Carlin

Joshua Light Show

(1967–72)

Of all the late 1960s light shows, as they were called at the time, the Joshua Light Show, in residence at New York’s Fillmore East, a former movie palace seating 2,500 or so spectators, was the strongest. The esthetic innovation was expanding the concept of the Lumia, or the THOMAS W ILFRED light box, to fill, in live time, a large translucent screen hung behind performing rock musicians. These lights were projected from several sources behind the screen, which at the Fillmore measured 30 feet by 20 and was always filled with bright and moving imagery. In the middle, usually within a circular frame (reflecting the glass bowl necessary to make it), were nonrepresentational, brilliantly colored shapes pulsating in beat to the music, changing their forms unpredictably (thanks to the fact that the colors were composed of oil, water, alcohol, glycerine, and other materials that do not mix). Around that frame was a less blatant, fairly constant pattern whose composition and color mysteriously changed through variations repeated in a regular rhythm (these coming from slides fading over one another).

Across the entire screen flashed rather diaphanous white shapes that irregularly fell in and out of patterns (these coming from an individual situated apart from the others, using a collection of mirrors to reflect white light onto the screen). From time to time representational images also appeared on the screen –sometimes words, at other times people; sometimes still, at other times moving. For instance, when musicians were tuning their instruments on stage, on the screen appeared a gag image of, say, Arturo Toscanini hushing his orchestra. (Those pictures came from slides and sometimes films.)

For good reason, the Joshua Light Show received a billing line directly under the musicians, for what it achieved in fact contributed enormously to the superior Fillmore theatrical experience, which wouldn’t have been the same without it.

Joyce, James

(2 February 1882–13 January 1941)

My job in a book like this is to distinguish the avant-garde Joyce from the more traditional writer. FINNEGANS WAKE obviously belongs and, if only to measure its extraordinary excellence, deserves a separate entry. For Joyce’s stories, Dubliners (1914), the innovation was the concept of the epiphany, which is the revelatory moment, customarily appearing near the end, that would give meaning to the entire fiction. “The epiphany is, in Christian terms, the ‘showing forth’ of Jesus Christ’s divinity to the Magi,” notes the British writer Martin Seymour-Smith (1928–98). “They are ‘sudden revelation[s] of the whatness of a thing,’ ‘sudden spiritual manifestation’ –in the vulgarity of speech or gesture or in a memorable phase of the mind itself.” Thus the departure of a Joycean story is the form not of an arc, where events proceed to a climax before retreating to a denouement, but of continuous events that establish a flat form until the flashing epiphany.

One innovation of U LYSSES (1922) is the elegant interior monologue, also called stream-of-consciousness. Retelling in many ways the story of an oafish Jew, who has as much resemblance to the classic Ulysses as a bulldog to a greyhound, this thick book incorporates a wealth of parodies, epiphanies, allusions, extended sentences, and contrary philosophies within a fairly conventional story.

What also distinguishes Joyce’s career is the escalation of his art, as each new book proved ever more extraordinary than its predecessor. The culmination was the W AKE (1939). One’s mind boggles at the notion of what Joyce might have produced had he lived twenty years longer. Indeed, this sense of esthetic awe, if not incredulity, is intrinsic in our appreciation of Joyce’s continuing high reputation. Another measure of awe is the sense that decades later his greatest works still aren’t completely understood. New insights continue to appear.

Joyce, Michael

(9 November 1945)

He was among the first (if not the first) certified literary writer to publish a hypertext, which became the initial epithet for a literary work reflecting the opportunities offered by the new technology called a computer. His afternoon, a story (1987) was not only a disk meant to be viewed on a Cathode Ray Tube but embedded within the narrative were options offered to the reader to pursue different turns in the plot. As a professor of English with an Iowa writing degree (customarily a badge of mediocrity), Joyce also published early substantial critical guides to unprecedented literary terrains –Of two minds: hypertext pedagogy and poetics (1995) and Othermindedness: the emergence of network culture (2000). One egregious default of the second edition of this Dictionary is not including this entry that could have been written then. This Joyce (not James) has continued working at the nexus of literature and computers with works in print, for galley exhibitions, and for CRT viewing.

Judd, Donald

(3 June 1928–12 February 1994)

A pioneer of MINIMALIST sculpture, Judd established his canonical reputation with the display of simple three-dimensional forms, devoid not just of any base but also of any fronts or sides. These objects were distributed in evenly measured ways, such as protruding three-dimensional rectangles up the side of a wall. Viewed from various angles, such definite forms suggest paradoxically a variety of interrelated shapes, for Judd’s point was to make one thing that could look like many things. With success, he used more expensive metals fabricated to his specifications, often with seductive monochromatic coloring, and produced many variations, only slightly different from one another, on a few ideas.

As a writer, Judd contributed regular reviews to the art magazines of the early 1960s, advocating the move away from emotional EXPRESSIONISM toward more intellectual structuring, and away from an earlier sense of art, particularly sculpture, as interrelated parts toward an idea of a single “holistic” image. Forever severe, he preferred to call his three-dimensional works “specific objects,” instead of sculpture.

Judson Dance Theater

(1962–64)

Out of the composition classes taught in the early 1960s by Robert Ellis Dunn (1928–96) at the MERCE C UNNINGHAM Studio came young dancers wanting to create their own pieces. As a Greenwich Village landmark (1877), which had already gained cultural fame, rare for a church at that time, by making its space available for a Poet’s Theater, The Judson Memorial Church was receptive to aspiring choreographers. The result was, in Sally Banes’s succinct summary,

the first avant-garde movement in dance theater since the modern dance of the 1930s and 1940s. The choreographers of the Judson Dance Theater radically questioned dance aesthetics, both in their dances and in their weekly discussions. They rejected the codification of both ballet and modern dance. They questioned the traditional dance concert format and explored the nature of dance performance. They also discovered a coop erative method for producing dance concerts.

The result was a rich succession of choreographic experiments, some more successful than others. In addition to involving dancers who subsequently had distinguished choreographic careers, such as YVONNE R AINER, TRISHA B ROWN, and LUCINDA C HILDS, the Judson Dance Theater hosted performances authored by such predominantly visual artists as ROBERT R AUSCHENBERG and ROBERT M ORRIS. New York’s MoMA mounted an exhibition remembering Judson Dance late in 2018.