T

Talbot, William Henry Fox

(11 February 1800–17 September 1877)

Talbot is generally regarded as the father of photography. He invented the negative-positive process that enabled the production of multiple prints on paper from a single negative, which became the basis of photography through the next century.

A brilliant student at Harrow and Trinity College in Cambridge, Talbot was graduated in 1825. At heart an accomplished scientist, he was elected to the Royal Society in 1831. Like earlier inventors, he experimented with salt and silver nitrate and the camera obscura (Latin for “dark chamber”), and the possibilities of fixing the reverse image that it projected. In August 1835 he produced what has become the first surviving negative, a 1-square-inch image of a latticed window, taken with an exposure time of about thirty minutes.

A scholar of many pursuits, Talbot left photography after those experiments, but in early January 1839, when he heard of the work of Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), he feared that he might not receive credit for his findings, so he presented his “photogenic drawings” on 25 January and described his experiments in a paper presented to the Royal Society on 31 January.

In 1843 he produced a book, The Pencil of Nature, with twenty-four photographs and text detailing the scope and potential of his calotype process. In June 1844 Talbot made a walking tour of Scotland and published a portfolio – the world’s first photo book without text – Sun Pictures of Scotland. Talbot went on to discover in 1851 a method for taking instantaneous pictures, invented a new photoengraving process the next year, and in 1854 created a traveler’s studio that combined a camera with two tanks, one for sensitizing wet plates and one for developing prints.

Much of Talbot’s work was of scenes in and around his home, Lacock Abbey (now a photography museum) and its environs. He usually created simple documents of 19th-century life. In 1855 Talbot won the Grand Medal of Honor in the Paris Exposition for his contributions to photography and another major prize in BERLIN in 1865. Though he had by then essentially retired from photography to concentrate on mathematical theory, he was made an honorary member of the Royal Photographic Society in 1873.

—Gloria S. and Fred W. McDarrah

“Talent”

This epithet is something glibly attributed to people working in the arts, though hard to measure, because not as respected as it used to be, particularly in the creation of innovative art, where, for instance, many important visual artists can scarcely “draw” and others overcome normally debilitating HANDICAPS.

My own sense is that imagination, likewise hard to measure, but certainly palpable in innovative work, is more crucial. So is courage, which is even harder to measure in advance, though eventually palpable as well. And so, finally, is work-work, which is to say the results of focused effort functioning at its highest imaginative level.

Taneraic

(August 1968)

Over the centuries, people have invented languages for many purposes. These planned languages often had one main purpose: to de-Babelize the globe, enabling people to live and function more comfortably and peacefully together. Other languagewrights had as their goal the development of a perfect language, a language that was logical, or a language that hearkened back to a pre-Babelian time when language was pure and singular, or a language without exceptions or ambiguity. All these languages failed, and the new ones invented continue to fail. But the planned language that succeeds the most in my mind is the hermetic language Taneraic. Devised by the Australian Javant Biarujia (8 August 1955), when the creator was only 13, Taneraic is a beautifully systematic language built not – as most planned languages are – on the roots of other languages, but out of the thin air of human imagination. The language developed from the modest cryptographic notations of a teenager into a language with inflections and set grammatical rules. Within two years of the inception of this language, Biarujia was using Taneraic to write a diary (quite Pepysian for a teenager), having studied English, French, Russian, Esperanto, and the national Creole of Indonesia on the way. By 1978, Javant Biarujia (both of whose names are Taneraic inventions) drifted away from the language, gave up writing a diary in Taneraic, and eventually began to forget his language. Having burned all the holographic Taneraic-English dictionaries, Biarujia discovered that the language was no longer open even to the inventor and had to rebuild and rediscover the vocabulary word by word. This act of invention (not of a play or a story or a painting, but of a language) so detailed, so exact, so real, to produce a language for the creator’s personal use alone, is the ultimate hermetic art: art for the artist’s sake. Occasionally, the lessons of learning the language are “poetic” in themselves: “Ava vayole esnula. Beqa an vayole esnula./We are friends. All of us are friends.” But what makes this language-making an art is the wonder the process creates, even as we can’t begin to fathom it all.

—Geof Huth

Tati, Jacques

(9 October 1908–5 November 1982; b. Jacques Tatischeff, reportedly of Russian-Dutch-Italian-French descent)

The most sophisticated of the modern comedy directors, Tati followed Chaplin’s precedent in both directing his films and playing the protagonist. Tati’s self-star is tall, gangling, clumsy, self-absorbed (if not oblivious) – a childlike innocent whose ignorance of social rules causes chaos around him. Because his second major film, Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot/Mister Hulot’s Holiday (1953) did not depend upon speech, it was an international success. Indeed, the soundtrack is a brilliant mixture of noises, human grunts, snatches of distant conversation in different languages, and much else that would be dismissed as aural garbage did it not enhance the ambience of comic chaos.

Tati’s first film, Jour de Fête (1949), portrays a provincial postman inspired by an American film about increasing efficiency. Mon Oncle (1958) was likewise an international success. Tati’s later films become more serious, their satire heavier (particularly in ridiculing modernization/Americanization), and less popular.

Financing for subsequent projects became more problematic. “Confusion,” announced in 1977, never materialized, though it would have been only his seventh film in a career spanning three decades. Their classic qualities notwithstanding, Tati’s films have had remarkably little influence, perhaps because, even after the development of cheaper videotape, such one-person creations are increasingly rare in feature-length filmmaking.

Tatlin, Vladimir

(28 December 1885–31 May 1953)

Commonly regarded as a founder and principal figure in Soviet C ONSTRUCTIVISM, Tatlin returned to Russia after a 1913 visit to PABLO P ICASSO’s Paris studio to make abstract reliefs composed of sub-art materials such as tin, glass, and wood. Always rivaling KAZIMIR M ALEVICH, Tatlin called his art Productivist (and later Constructivist), in contrast to Malevich’s Suprematism. Nonetheless, their purposes were complementary. As the Paris art historian Andrei B. Nakov (1941) succinctly put it, “Tatlin’s sculpture is really free of any connection to extra-artistic reality in the same way as Malevich’s suprematist forms are purely non-illusionistic.”

Once the Soviet Revolution succeeded, the government’s Department of Fine Arts commissioned Tatlin to design a Monument to the Third International (1919), which he exhibited only as a model. With a continuous sloping line resembling that of a roller coaster, this was intended to be 2,000 feet high and to contain assembly halls, smaller spaces for executive committee meetings, all within a central Lucite cylinder that would revolve mechanically. Though his proposal was never executed, thus exemplifying CONCEPTUAL ARCHITECTURE, the architectural historian Kenneth Frampton (1930), for one, has measured, “Few projects in the history of contemporary architecture can compare in impact or influence to Vladimir Tatlin’s 1920 design.”

After the Stalinist crackdown on vanguard art, Tatlin worked mostly on more modest applied projects, such as furniture design, workers’ clothing, and the like. Beginning in the late 1920s, he spent several years designing a glider plane that he called Latatlin. Though he died from food poisoning in Moscow in relative obscurity, an exhibition mounted there in 1977 included paintings, book illustrations, and stage designs. In PONTUS HULTÉN’s mammoth Paris-Moscow traveling show (1979), which I saw in Moscow in 1981, Tatlin was clearly portrayed as a lost star, the exhibition there featuring his Letatlin.

Tattooing

(forever)

This is the modern name of a body art that comes from making permanent designs and drawings on human skin. In certain cultures, appropriate design can represent status. In others, such as modern America prior to 1980, tattoos generally reflected declassé living. They have since become more acceptable among the bourgeois in Western cultures, or at least their children, initially on body parts customarily covered by clothing, but more recently not. The most ingenious tattoos exploit the peculiar luminescence of human skin, or perhaps body movement, so that an image changes shape when a body part moves, etc.

For some, the next step was piercing the body, not just in the ears, as women have done for decades, but elsewhere – nose, tongue, private parts of both men and women, often prompting questions, if not conversation, in otherwise icy social circumstances. Scholars appreciative of artistic tattooing, such as Professor Mark Taylor (1945, religion, Columbia U.), have traced it back to the Edo period of Japan at the beginning of the 17th century.

Though this entry, requested by my second publisher as our book was going to press, is finally too P OSTMODERN, too post-1980s, for my taste, it is reprinted here.

Tavel, Ronald

(17 May 1936–23 May 2009)

The superficial record of his career identifies him as a principal contributor to the Theater of the Ridiculous, a 1960s development that was regarded as a successor to the THEATRE OF THE ABSURD. The credits for several ANDY WARHOL films, including The Chelsea Girls (1967) and Vinyl (1965), name Tavel as the scenarist.

The hidden history is that around that time he also published an extraordinary novel probably more distinguished than his plays. Street of Stairs (1968) takes place in Tangiers, in which a large number of narrators, perhaps forty, tell of life in a circuitous, mysterious city. Some of the more striking passages reproduce a lingo unique to the place:

Soden we shewit dirty fotografias, askin 3,00 francos por todo el colección. No needit! gettim in Neuva York! him says end looksit for mad. – D’acuerdo, you want for see dirty bad cine.

Actually an abridgment of a manuscript reportedly at least twice as long, this edition was meant to prompt sufficient interest to persuade a publisher to do the longer version. That never happened. Disillusioned with America, Tavel resided mostly in southeast Asia before his unfortunate death of a heart attack on a flight from BERLIN to Bangkok.

Tavener, John

(28 January 1944–12 November 2013)

Many people whose taste I respect consider Tavener the strongest composer of his (my) generation, recently in late middle age. Whether his music is avant-garde is an open question. On the one hand, he assimilated serial music and electronics; on the other hand, after his conversion to Greek Orthodoxy in 1976, his compositions often sound quasi-medieval in conventional forms, with standard instrumentation.

His solo pieces, especially for cello, sound pure and meditative, while his choral works, often commissioned for public occasions, sound impure and bombastic. One oddity that I saw at Lincoln Center in the summer of 2002 was The Veil of the Temple that began late at night to go into the following morning. Supposedly about “spiritual reflection and transcendence,” incorporating stretches of silence, it was impressively ambitious.

Perhaps this contemporary kind of neoclassicism accounts for why his music is frequently recorded in his native Britain. His name is often confused with that of John Taverner (c. 1490–1545), spelled slightly differently, whose music is authentically medieval.

Taylor, Cecil

(15 March 1929)

A reclusive musician who rarely performs and whose few available recordings are reportedly not always authoritative, Taylor is one of those rare NEW YORK CITY artists whose reputation gains from personal absence. Active as an African-American JAZZ pianist, poet, composer, and bandleader since the late 1950s, Taylor took compositional ideas from European Impressionism, relying more on tone and texture than rhythm and melody. His improvisations often featured highly energetic articulations, jagged starts and stops, abrupt changes in mood, and ever-shifting structures often devoid of melody or beat. Eschewing harmonic landmarks, he refuses to use a bassist; and when he plays piano behind a soloist, Taylor’s improvisations are less complementary than independent. When I heard his Black Goat performed at New York’s Metropolitan Museum in 1972, I found his favorite structure to be a succession of sounds, quickly articulated and followed by a pause, so that individual instrumentalists played vertical clusters at varying speeds. He also writes and sometimes recites his own odd poetry.

Tchelitchew, Pavel

(21 September 1898–31 July 1957)

Hide and Seek (1942), which was long permanently exhibited at the MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, is a uniquely eccentric painting that assembled a larger image from smaller complimentary images whose different identity became visible only on close viewing. Measuring over 6½’ by 7’, it especially instructed children (including myself once) about the possible ambiguities of painting, in this case about small children’s heads composing images of larger heads. (Decades later, after it was stored away, I miss seeing it again in visiting MoMA.)

Otherwise, Tchelitchew had a rich career as a designer of theatrical costumes and sets, incidentally contributing illustrations to VIEW, which was edited by CHARLES HENRI FORD and Parker Tyler (1904–74), a film critic who published a lush biography of Tchelitchew (1967), whose name is best pronounced as Che-LEE-schev (with a soft SCH as in “sheer”).

Teachers

Not only do the greatest produce their own avant-garde work but they teach many who later do likewise. In painting, few score as high as FERNAND LEGÉR; in classical music composition, the champs were ROGER SESSIONS and OLIVIER MESSIAEN. Whereas the three of them had many students, JOHN CAGE had fewer, mostly at New York’s New School in the 1950s where several in his class pursued visible careers. FREDERICK SCHWANKOVSKY should be remembered for teaching the painters JACKSON POLLOCK and Philip Guston while both were still in high school. In modern dance, most aspiring choreographers learn by dancing in senior choreographers’ companies, much as baseball players learn to manage a team by playing under senior managers. The reputation of college-level sports coaches, say, should depend not only upon how many games they win but by how many alumni become professionals. By this measure, the greatest were Eddie Robinson (1919–2007) at Grambling, John Wooden (1910–2010) at UCLA, and Joseph Paterno (1926–2012) at Penn State.

It is unfortunate that too many courses in university creative writing and art are designed to teach not the making of distinguished work but what the teacher does (or did), ideally to pass whatever onto their students’ students and then their students’ students’ students.

Superior teachers of art and writing also encourage greater esthetic intelligence in many more sometime students (than those who become professionals), beginning with their appreciation of excellence, though these effects are harder to measure.

Teige, Karel

(13 December 1900–1 October 1951)

A true POLYARTIST in Czechoslovakia, Teige worked with distinction in graphic design and architectural proposals, poetry, and PERFORMANCE. Reflecting the influence of the BAUHAUS in nearby Germany, he favored CONSTRUCTIVISM that he blended not with DADA, as MOHOLY-NAGY did, but with SURREALISM. He thus preferred sensual, if not erotic imagery, within frames composed of horizontal, vertical, and parabolic lines. Typically, a 1938 Teige photo-collage portrays a woman with gartered stockings in a Moscow subway station with a semi-circular ceiling. Later, he advocated the creation of Surrealist parks with abstract sculpture inspired by the human body.

In 1920, while young, he joined other radical Czech avant-gardists in founding a group calling itself Devetsil, whose name refers to a common weed while combining the Czech words for Nine and Force. The group advocated unity among the various art forms and so produced not only book anthologies but also artistic festivals. Teige both edited and designed the principal publication, Red (1927–31), the name an abbreviation for Revue Devetsil, which published Czech avant-gardists besides international celebrities.

Once the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia in 1939, Teige worked in internal exile. Though his earlier political biases predisposed him to favor the Soviet occupation of his homeland, he quickly fell victim to Stalinist authorities, who forbade him to publish or organize artistic activities. He died prematurely in 1951 of a heart attack, which is customarily understood to reflect a broken heart. The Communist state police, never kindly to avant-garde artists, reportedly confiscated all of his personal effects. If only for his attempt to make innovative art for larger publics, Teige was featured, along with JOHN HEARTFIELD, EL LISSSITZKY, and GUSTAV KLUTCIS, in the exhibition and book Avant-Garde Art in Everyday Life (2011).

Telegraphic Writing

(20th century)

A major literary departure in the 20th century, reflecting a technological invention outside literature, was the development of prose whose elliptical conciseness reflected the development of telegraphy. As messages sent through the new technology, unlike those in a letter sent through the post, had a cost per word, economics prompted senders to drop all words not deemed essential. Another mark of a telegram was containing only uppercase letters that, in turn, visually defined telegraphic style when it appeared in literary books.

This style evolved in the 1990s with the invention of texting (sending short messages between computers and cell phones) that resulted in a more extreme post-telegraphic reduction because not words, but characters were limited in number. In the 21st century innumerable inventive abbreviations used in electronic messaging were joined by emoticons (punctuation marks arranged to resemble facial expressions) and emojis (small digital pictures representing feelings or concepts), thus further extending the impetus to contraction in literary communication.

—with Shoshana Esther Stone

Television

(c. 1930s)

By adding sound to radio, television should have been hospitable to an avant-garde art; but precisely because it became so quickly a commercial medium for universal dissemination, that opportunity rapidly succumbed to the American genius for mass-merchandising a new technology that Europeans thought would belong exclusively to the elite (whether automobiles or motion pictures before television, or portable computers afterwards).

Nonetheless, some imaginative early performers used television in ways radically different from the common run, exploiting capabilities unavailable in film and live performance. Before the age of videotape and thus in live time, the comedian Ernie Kovacs (1919–62) tilted his camera to create the illusion that coffee was being poured at a diagonal impossible in life; he used two cameras to situate himself inside a milk bottle; he used smoke from a Sterno can to blur focus; he put two separate images in a split screen; he composed live video accompaniments to the warhorses of classical music; and he used an electronic switch to make half the screen mirror the other, enabling him to stage interviews and even sword fights with himself, etc. Because of the small scale of the early TV monitors (compared to the much larger movie screen or later television receivers), Kovacs was able to stage close-up sight gags: His femme fatale would, in David G. Walley’s words, “slowly turn her head to an admiring camera and then catch a pie in the face,” in an image that would not work as well on a big screen (and not at all on radio).

Once videotaping was developed, producers could use such devices as instant replay for essentially MODERNIST techniques such as scrambling continuous time. Indeed, most innovations in broadcast television in the past quarter-century have come less from tinkering with the medium itself than from ingenuity with videotape and then digital storage. A further implication of the dissemination of the portable video camera and then the INTERNET was the possibility of circumventing television stations in the creation and distribution of VIDEO ART.

Ter Oganian, Avdey

(9 December 1961)

One variation upon artistic appropriation is Avdei Ter Oganyan’s portentously titled Some Questions of Contemporary Art Restoration (1993). It is essentially a men’s room urinal resembling Marcel Duchamp’s historic GESTURE that, having been smashed in the past, is visibly repaired with glue, which is to say that, even though it drew upon the same material (and alluded to a Duchamp sculpture likewise repaired from breakage), TO’s Some Questions would never be mistaken for the original. Once making a fairly accurate replica of a Jasper Johns encaustic painting, he left it outdoors in the Moscow rain, again producing a defective copy with considerably ironic weight.

The epithet iconoclasm more accurately describes his work than others often so dubbed. In a 1998 Moscow art fair, Ter Oganyan performed an action he variously called “Young Atheist” or “Desecration of Holy Objects” during which he chopped up mass-produced Russian Orthodox icons with an axe and wrote obscene words on their faces. Visitors were also invited further to destroy icons themselves for a small payment. After a Russian court declared Ter Oganyan guilty of inciting religious hatred, he earned political asylum in Prague.

Text-Sound

(forever)

As distinct from text-print and text-seen, text-sound refers to texts that must be sounded and thus heard to be “read,” in contrast to those that must be printed and thus seen. The term “text-sound” is preferable to “sound-text,” if only to acknowledge the initial presence of a text, which is subject to aural enhancements more typical of music. To be precise, it is by nonmelodic auditory structures that language or verbal sounds are poetically charged with meanings or resonances they would not otherwise have.

An elementary example is the tongue twister, which is literally about variations on a particular consonant. This term is also preferable to “sound poetry” because several writers working in this area, including GERTRUDE S TEIN and W. BLIEM K ERN, produced works that, even in their emphasis on sound, are closer to prose than poetry. Only in recent times have we become aware of text-sound as a true INTERMEDIUM between language arts on the one side and musical arts on the other, drawing upon each but lying between both, and thus, as a measure of its newness, often unacceptable to purists based in each.

Tharp, Twyla

(1 July 1941)

Those familiar with Tharp’s later choreography, so popular in larger theaters, can hardly believe, or remember, that her dance was once avant-garde. At the beginning of her choreographic career, in the late 1960s, Tharp created a series of rigorously CONSTRUCTIVIST works that, in their constrained style, were never exceeded. Using only female dancers (and thus excluding any of the customary themes dependent upon sexual difference), she choreographed pieces such as Group Activities (1968), in which ten dancers, including herself, perform individualized instructions, themselves derived from a numerical system, on two sets of checkerboard-like floor spaces, creating an asymmetrical field of animate patterns, all to the accompaniment of only a ticking metronome. Performed totally without sound accompaniment on an unadorned stage, Disperse (1967) depends upon the ratio of 2:3, which requires the stage lighting to turn ever darker as the dancers move progressively into the right rear corner.

In The One Hundreds (1970), Tharp recruited members of the audience to execute one hundred phrases. Her credo at the time: “Dance belonged to everyone, and everyone could be a dancer if the material was appropriate to them.” Tharp around that time also choreographed dances for previously unexploited spaces, such as Manhattan’s Central Park in the late afternoon. (I remember a rugby game beginning on an adjacent field.) About Tharp’s Medley (1969), which I saw on a parade ground the size of two football fields, someone (perhaps I) wrote:

With the audience seated on a slope at one end, six girls in Miss Tharp’s company were at the other end of the field, looking small and remote. Gradually they moved closer, but never close enough for the public to see the intricate detail of the choreography. The climax of the performance came when thirty students joined the group and commenced one long sequence in which each person moved at the slowest possible speed, giving the effect of a field full of statues in a continuous but imperceptible state of change.

Dance in the Streets of London and Paris, Continued in Stockholm and Sometimes Madrid had its premiere on two floors of the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut. As the critic Don McDonagh (1932) remembers it,

The audience flowed in and around the performers at all levels and at times trailed them from one floor to another. There was no set position from which to view the dance… the nine dancers kept in touch with one another by means of verbal time checks called up the stairwell and by the use of video monitors connected to a closed-circuit television hookup between the various galleries.

Composed in sections, this Tharp dance could be recreated to suit different venues.

If you don’t believe my recollections of Tharp’s earlier choreography, consider this from The Performing Arts in America (1973): “Twyla Tharp is a choreographer whose ballets have no plot, no reference to character or emotion, no scenery or props, costumes only very rarely, and, above all, no music.” In this history of Tharp’s art, that was centuries ago.

Theater of the Absurd

See ABSURD, THEATER OF THE.

Theater of Cruelty

See ARTAUD, Antonin.

Theatrical Décor

(20th century)

To no surprise perhaps, the great innovations in this normally sleepy art (and sometimes in costumes as well) have come from prominent visual artists. Among the more memorable (decades later) were those by the Norwegian Edvard Munch (1863–1944) for Henrik Ibsen productions in Paris early in the 20th century; PABLO PICASSO’s for Manuel de Falla’s Le Tricorne (1919), IGOR STRAVINSKY’s Pulcinella (1920), and de Falla’s Flamenco (1921); JEAN COCTEAU’s for Darius Milhaud’s Le Bœuf Sur Le Toit (1920); FERNAND LEGÉR’s for both Artur Honegger’s Skating Rink (1922) and Milhaud’s Le Création du Monde (1923); and DAVID HOCKNEY’s famously for Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress (1975). MERCE CUNNINGHAM routinely commissioned painters to decorate his choreographies. In my own recent opera-going experience, few stage decorators can rival WILLIAM KENTRIDGE.

Themerson, Stefan

(25 January 1910–6 September 1988)

Born in Poland, Themerson was initially a Warsaw painter who also made an avant-garde film, Europa (1931), that subsequently disappeared. Working with his wife Franciszka (1907–88), according to the Encyclopedia of European Cinema (1995), “They invented an apparatus for making photograms in motion, scratched and painted on film, and fused animation and photo-montage with live action.” After serving in the Polish army in France during World War II, Stefan Themerson escaped Communism by emigrating to England, where he and his wife resided until their deaths, publishing poetry, fiction, and unclassifiable experimental writings almost exclusively in English, mostly with the marvelously titled Gaberbocchus Press (1948): among them, the novels Bayamus (1949, which includes typographic poetry), The Adventures of Peddy Bottom (1951), Cardinal Polatuo (1961), and Tom Harris (1967); philosophical essays with titles such as factor T (1972); and St. Francis and the Wolf of Gubbio or Brother Francis’ Lamb Chops (1972), “an opera in two acts,” complete with a musical score, handwritten plot summaries, and sketches for stage designs (which is, of course, how proposed operas should be published). Respectful of avant-garde traditions, Themerson also produced a memoir, Kurt Schwitters in England (1958), the first English translation of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi (1951), and, in a large-page format, an early English edition of Apollinaire’s Lyrical Ideograms (1968). A visual-verbal masterpiece is his “Kurt Schwitters on a Time Chart,” which initially appeared in the British magazine Typographica # 16 and then as a book published in Holland (1998).

It is unfortunate that Themerson’s work isn’t often mentioned in histories of contemporary British literature, perhaps because like several other authors of avant-garde English literature written in Britain after World War II, he was born outside of the British Isles.

“Theory”

(1980–2010)

This epithet identified a highfaluting mode of cultural explanation, not quite thinking, was during its heyday disliked by nearly everyone except its advocates, who necessarily strived for power in academic institutions. Inherently fanciful, often politically prejudiced simplistically, “theory” was more popular with professors of literature and philosophy than, say, with historians, who are by training more respectful of verifiable facts. Successful for a while, the epithet fell into disuse when its publicists retired or passed away. Art purportedly informed theoretically was short-lived, as balloons inevitably pop, to the surprise only of those clutching them. As BUCKMINSTER FULLER persuasively proclaimed as he watched the nickel he tossed into the air fall to the floor, “Nature’s 100% reliable.”

Theremin

(c. 1920)

One of the earliest ELECTRONIC instruments, named after its creator Léon Theremin (1896–1993; b. Lev Sergeyevich Termen), who invented it just after the First World War, this consists of two antenna emerging perpendicularly from a metal cabinet. Both poles respond not to touch, like traditional instruments, but to hand movements in the electrified air immediately around them. (Roberta Reeder and Claas Cordes write, “He created his instrument while working on an alarm system to protect the diamond collection at the Kremlin,” which seems obvious in retrospect.)

One antenna controls the instrument’s pitch, the other its volume, together producing sustained, tremulous sounds that were particularly popular in horror films in the 1930s and 1940s. The principal Thereminist in America, if not the world, was Clara Rockmore (1911–98). One of Rockmore’s long-playing records was produced by ROBERT M OOG, who, before he made the SYNTHESIZER bearing his name, manufactured Theremins. More familiarly, a Theremin accompanied a cello to produce the “Good Vibrations” in a 1966 Beach Boys recording of the same name.

During his eleven years in America (1927–38), Léon Theremin, according to his countryman NICOLAS S LONIMSKY,

on April 29, 1930, presented a concert with an ensemble of ten of his instruments, also introducing a space-controlled synthesis of color and music. On 1 April 1932, in the same hall, he introduced the first electrical symphony orchestra, conducted by Stoessel, including Theremin fingerboard and keyboard instruments. He also invented the Rhythmicon [with HENRY C OWELL], for playing different rhythms simultaneously.

Theremin disappeared from New York in 1938 and was thought dead until he emerged from post-Soviet Russia in 1991, by then well into his nineties, to attend European music festivals.

An illuminating biography (2000) by Albert Glinsky (1952) reports that Theremin, a devout Communist, voluntarily returned to the Soviet Union where he was imprisoned but kept alive to work especially on perfecting electronics for eavesdropping (including a self-powered bug embedded in a wall sculpture given to the American embassy in Moscow!). In the 1990s, in his own nineties, Theremin returned to New York City for a visit that is memorialized in an eponymous documentary film by Stephen Martin (1993).

Thomas, Dylan

(27 October 1914–9 November 1953)

Dylan Thomas was the first modern poet whose work was best “published,” best made public, not on the printed page or in the public auditorium but through electronic media, beginning with live radio, eventually including records and audiotape. So strongly did Thomas establish how his words should sound that it is hard not to hear his voice as you read his poetry; his interpretations put at a disadvantage anyone else who has tried to declaim his words since. Some failed to notice that he also exploited extended silences often a minute in length. It is not surprising that he also became the first prominent English-speaking poet to earn much of his income initially not from writing or teaching but from radio recitals, mostly for the British Broadcasting Corporation. (Given the American media’s lack of interest in poetry, it is indicative that Thomas’s sole peer as a reader of his own verse, Carl Sandburg [1878–1967], a quarter-century older, made his living mostly as a traveling performer of considerably less difficult poetry.)

In 1946, Edward Sackville-West (1901–65) gushed:

A verbal steeplejack, Mr. Thomas scales the dizziest heights of romantic eloquence. Joycean portmanteau words, toppling castles of alliteration, a virtuoso delivery which shirked no risk – this was radio at its purest and a superb justification of its right to be considered as an art in itself.

Indeed, it could be said that the principal recurring deficiency of Thomas’s prose is the pointless garrulousness, filling space with verbiage, that we associate with broadcasting at its least consequential.

Thomas’s Collected Poems (1952) reportedly sold 30,000 copies within a year after its publication – a number no less spectacular then than now – so popular did his own brilliant declamation make a difficult poet.

Thompson, Francis

(3 January 1908–26 December 2003; b. Eben F. T.)

Though initially a painter, Thompson made several masterpieces of experimental short film that are generally omitted from histories and encyclopedias of the medium. The first short, New York, New York (1958, 18 min.), views the city through distorting prisms that function to exaggerate through visual abstraction its distance from nature. The second, To Be Alive (1962, also 18 min.), made with ALEXANDER HAMMID for the Johnson Wax Pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, used three screens, of standard ratios of height and width, but with 15 inches between each one to distinguish them from the continuous horizontal screens of CINEMASCOPE and C INERAMA, which had been developed in the decade before. To Be Alive opens with high-speed shots of NEW YORK CITY simultaneously on three screens and subsequently depicts the maturation of people around the world. In one sequence, a prepubescent American boy is learning to ride a bicycle on one screen, a young Italian is learning to paddle a boat, and a similarly young African is learning to ride a mule. Disaster hits each simultaneously, prompting them to cry in unison. For many years after, To Be Alive was screened continuously at the Johnson Wax Factory in Racine, Wisconsin. For Hemisfair (San Antonio, 1968), Thompson and Hammid made US, which begins with the audience divided into three parts of a circle. When the walls between them are taken up, they are watching a circle surrounded by three screens, each 145 feet wide.

For the Canadian Pacific pavilion at EXPO ’67 in Montreal, Thompson and Hammid made We Are Young (1967, likewise 18 mins.) for six separate screens. The three screens in the lower row were roughly 30 feet square; the three in the upper row were a little wider, much lower, and pushed forward about a foot in front of those below. As in To Be Alive, each screen is clearly separated from the others. Sometimes all six screens present the same image synchronously; at other times only one screen is used (while the others are blank). One particularly stunning sequence has the audience moving down six railway tracks simultaneously, each one turned to be perpendicular to the top of the bottom middle screen, the sound of six trains emerging from the amplification system. It seems inappropriate to write about this film as though it may still be available, because once the original venue was dismantled it was never seen again and, according to the filmmaker, may not even exist any longer.

Having established a unique competence with expanded image films, Thompson produced several films in 70 mm. IMAX technology, including To Fly (1976), which, also at eighteen minutes, is an aerial tour of America from balloon ascent in the 1890s to space flight; American Years (1976, 45 mins.), which celebrates Philadelphia’s bicentennial as the first historic film show in IMAX. In 1998, Thompson at the age of 90 received from the LFCA (Large Format Cinema Association) the ABEL G ANCE Lifetime Achievement Award, its name recalling the man whose films Thompson saw in Paris in the early 1930s, as his first exposure to the fertile possibility of multiple projection. The British poet similarly named F. T. (1859–1907) was someone else.

Thomson, Virgil

(25 November 1896–30 September 1989)

A conservative tonal composer of rather simple works, Thomson had the good fortune to get involved in the mid-1920s with GERTRUDE S TEIN, his fellow American in Paris. Out of their collaboration came first “Capital Capitals” (1927), a uniquely brilliant (if under-recognized) art song for four male voices, and then Four Saints in Three Acts (1927–29), more famous, which was probably the most impressive deviant modern opera of its time. The plot was incomprehensible; so, at first, was much of the language. The sets by the New York painter Florine Stettheimer (1871–1948) featured cellophane. All the performers were African-Americans, whom Thomson favored not only for the theatrical value of skin color but for their superior competence at clearly singing English words. (Some identify this as the first prominent 19th-century appearance of many blacks in roles that could have been given to whites.) The excellence of Four Saints depended on Thomson’s inventive settings of Stein’s fanciful, often repeated lyrics:

Pigeons on the grass alas

Shorter long grass short longer longer shorter yel low grass

Pigeons large pigeons on the shorter longer yellow grass also

Pigeons on the grass

To measure the difference, just compare Four Saints on the one hand with the colloquial slickness of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (1935) and, on another hand, the forgotten pseudo-traditional operas produced in the 1920s and ’30s. Though Thomson and Stein had to wait several years for the Four Saints premiere, which occurred in 1934, not in New York but in Hartford, CT, it received enough acclaim to have a Broadway run. A later Thomson-Stein collaboration, The Mother of Us All (1947), was less successful. By illustrative contrast, Thomson’s appropriation of Stein’s “Portraits,” which was a lesser genre for her, produced without her words lesser music for him.

As chief music critic at the New York Herald-Tribune from 1940 to 1954, Thomson also wrote some of the strongest music criticism, measured sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, though his neglect of younger avant-garde composers makes him appear conservative in retrospect. The problem, in short, was that Thomson didn’t learn enough from Stein to advance his musical taste.

The first fat biography of Thomson is a monumentally inept classic, as a humorless enthusiast produces page after thick page on a man renowned for his wit. Composer on the Aisle (1997) must be read to be believed. Consider how such books get written and then published, let alone blurbed and reviewed by colleagues with reputations to protect, and you can lament the decline of literary intelligence in America, or maybe just the evaporation of humor to a level more typical of, say, Soviet Russia.

Tiffany, Louis Comfort

(18 February 1848–17 January 1933)

Tiffany belongs here, no joke, because he repudiated ornate complexity fashionable in the mid-19th century to design glass lamp fixtures and window screens with uncommon geometries. Commonly classified as Art Nouveau, many Tiffany designs resemble Islamic art in their scrupulous avoidance of representation and thus suggest geometric ABSTRACT A RT done decades later. Beginning as an Impressionist painter, Tiffany studied glassmaking in the 1870s and, at the end of that decade, opened a business devoted to interior decoration. In 1880, he parented “favrile” glass that had an iridescent finish. Quickly recognized for excellence, his firm was invited to redecorate the august White House in 1883–84. Tiffany persuaded churchmen to accept stained-glass windows with secular subjects. In his own time he was probably the best-known American artist in Europe.

One of the most exquisite permanent exhibitions in Manhattan is that devoted to Tiffany’s art in, of all places, the New York Historical Society. He was the son of Charles L. Tiffany (1812–1902), who founded an eponymous New York jewelry firm, whose name is synonymous with superfluous luxury, which was perhaps a misfortune for the son, whose art realized elegant purity.

Times Square Show

See NINTH STREET SHOW.

Tobey, Mark

(11 December 1890–24 April 1976)

Before becoming a profoundly original American painter, Tobey joined the Bahá’í religious movement and then studied calligraphy both in Seattle and in Shanghai. He was well into his forties before discovering his innovative calligraphic “white writing,” in which an unmodulated collection of lines, roughly equal in width, run to the edges of the image, at times creating a shimmering surface. As in the careers of KAZIMIR M ALEVICH and PIET M ONDRIAN before him, the turn to ABSTRACTION devoid of Nature reflected his religious faith, the Bahá’i believing in a common humanity and accessibility to all, notwithstanding cultural differences. Such Tobey paintings, also avoiding visual anchors, presaged the all-over images of a later generation (as JACKSON POLLOCK reportedly studied them closely) as well as both the OPTICAL A RT and monochromic painting of subsequent periods. In the late 1950s, Tobey began to use broader strokes, as well as other colors, including black. Not unlike other spiritual Abstractionists, he had a taste for strong prose statements: “At a time when experimentation expresses itself in all forms of life, search becomes the only valid expression of the spirit.”

Tolson, Melvin

(6 February 1898–29 August 1966)

A professor who spent his entire adult life teaching at historic black colleges and coaching consistently successful varsity debate teams, Tolson was also a poet who raised outrageous parody to high literary levels. He was a great American DADA poet, though scarcely recognized as such, as he ridiculed the allusive techniques of the great moderns, beginning with self-conscious obscurity, in the same breath as certain African-American myths about Africa and much else:

The Höhere of God’s stepchildren is beyond the sabotaged world, is beyond das Diktat der Menschenverachtung,

la muerte sobre el esqueleto de la nada,

the pelican’s breast rent red to feed the young, summer’s third-class ticket, the Revue des morts, the skulls trepanned to hold ideas plucked from dung,

Dives’ crumbs in the church of the unchurched, absurd life shaking its ass’s ears among the colors of vowels and Harrar blacks with Nessus shirts from Europe on their backs.

Perhaps because such lines offend as they honor (and were easily misunderstood as well), they were not easily published. Though his books appeared from general publishers, it is unfortunate that most recognition of Tolson’s innovative work has appeared in special situations reserved for African-American writers.

Tomlin, Bradley Walker

(19 August 1899–11 May 1953)

An abstract painter at a time when realisms were more fashionable, he sought to represent his unconscious not with lines, as in JACKSON POLLOCK, but with overlapping planes of various sizes and shapes in a crowded field. To some eyes, his strongest work approaches calligraphy with semblances of thick letters appearing mysteriously at varying degrees of depth. Tomlin’s In Praise of Gertrude Stein (1950) rivals PABLO PICASSO’s more famous portrait in honoring her. His masterpiece is the black and white Tension by Moonlight (1948), 32 inches by 44 inches. As Tomlin’s art matured only in the late 1940s, his strongest works appeared in the last five years of his shortened life.

Tondo

(15th century; probably before)

In contrast to rectangular formats for framing visual art, this circular form has become a profound constraint conducive to alternative imagery and structure. Used memorably by Michelangelo to portray The Holy Family (1506/08), the shape of tondo becomes an implicit halo. A circle also became the preferred form for medallions, or surrogate coins, sometimes with an image in relief. Among modern artists doing in a circle what cannot be done in a rectangle were ILYA BOLOTOWSKY especially, WILLIAM KENTRIDGE. JACKSON POLLOCK, SOL LEWITT, and L. MOHOLY-NAGY. Among those writers working with words in circles, rather than horizontal lines – making literary tondos, so to speak – are GERTRUDE STEIN, FERDINAND KRIWET, and myself. May we be surprised that no substantial book of art history/ criticism has been written about tondos.

Tone Clusters

(1912)

The technique of tone clusters was demonstrated for the first time in public by HENRY C OWELL at the San Francisco Music Club on 12 March 1912, on the day after his fifteenth birthday. It consists of striking a pandiatonic complex of two octaves on white keys, using one’s forearm, or a panpentatonic set of black keys, as well as groups of 3 or 4 notes struck with the fists or the elbow. Cowell notated the tone clusters by a thick black line on a stem for rapid notes or a white-note rod attached to a stem for half-notes. By a remarkable coincidence, the Russian composer Vladimir Rebikov made use of the same device, with an identical notation, at about the same time, in a piano piece entitled Hymn to Inca. Still earlier, CHARLES I VES made use of tone clusters in his Concord Sonata, to be played with a wood plank to depress the keys. Béla Bartók used tone clusters to be played by the palm of the hand in his Second Piano Concerto, a device that he borrowed expressly from Cowell, by permission.

—Nicolas Slonimsky

Torre, Guillermo DE

(1900–14 January 1971)

Born in Spain, where his literary talents were recognized while still a teenager, he drafted around 1920 a “Vertical Manifesto” for a movement titled Ultraism. Around the same time he collaborated in writing an automatic poem with TZARA and BORGES, whose sister he later married. Torre’s early poems, collected as Hélices (1923), includes calligrams and some of the first haiku written in Spanish.

At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, Torre fled to Paris before resettling in Buenos Aires, where he became a professor of literature, an influential literary critic, and a first-rank literary historian. His major critical achievement was an expanding, essentially correct history of avant-garde literature that went through several editions. The 1925 first edition, Literaturas europeas de vanguardia, contained 390 pages, and was reprinted in 2001 and 2002. A greatly expanded second edition of 946 pages, Historia de las literaturas de vanguardia appeared in 1965, and was reprinted in 1971 in both one volume, and three smaller volumes of 363, 334, & 297 pages. Though translated into Portuguese, this has never been Englished. (I knew around 1964 an experienced translator, my former professor’s wife, who wanted to do it, only to be blocked when Professor Roger Shattuck gave it a negative notice.) Nonetheless, nothing else treats its subject so hugely and thoroughly.

Torres-García, Joaquín

(28 July 1874–8 August 1949)

Born in Montevideo of a Catalan father and a Uruguayan mother, Torres-García studied and worked in Spain before coming in 1920 to New York, where he shared a studio with the painter STUART D AVIS at the Whitney Studio Club, making wooden toys that presaged his later CONSTRUCTIVIST painting. Relocating to Europe in 1922, Torres-García lived in Paris, where he befriended THEO VAN D OESBURG, PIET M ONDRIAN, and MICHEL S EUPHOR, among others. Then in his forties, Torres-García collaborated with Seuphor in founding the periodical CERCLE ET CARRÉ and in organizing the first major ABSTRACT A RT exhibition (1930) with over eighty artists. Though I’ve never seen a copy firsthand (and don’t know where to find), reproductions and descriptions suggest that Torres-García’s Structures (1931), a sort of visual scrapbook, ranks as monumental BOOK-ART.

Mindful of his different origins, he also organized the first exhibition in Paris of such Latin American artists as the Mexican muralists J OSÉ CLEMENTE O ROZCO and DIEGO R IVERA. Returning to his native Uruguay in 1933, after more than four decades away, Torres-García published manifestos, organized the Asociación Arte Constructivo, lectured widely, and founded both an art school and two magazines, in addition to writing a thousand-page book, Constructive Universalism (1944). His idiosyncratic paintings favored ideographic images within a grid. Though his name may be forgotten in Europe and North America, Torres-García was one of those modernists who redirected the course of Latin American culture.

Transfurists

The only Russian group in the post-Stalin period to have a close relationship to the RUSSIAN F UTURISTS consists of a husband and wife team, SERGE S EGAY and REA N IKONOVA and Nikonova’s brother-in-law, BORIS K ONSTRIKTOR, plus a number of other, less constant associates. Their orientation toward the original avant-garde began in the 1960s in Sverdlovsk (now, again, Yekaterinburg) under the name of the Uktus School (1964–74), after a local ski jump, and from the beginning included experimental activities in the visual and verbal arts simultaneously. While some of their works were not innovative when compared with developments in the West, they were created independently, since access to Western sources of information was somewhat limited at the time. Nikonova and Segay published a journal, Nomer (1965–75, 35 issues) in one copy; and the group was one of the first to produce works of a minimalist or conceptualist sort. After the couple returned to Nikonova’s birthplace of Yeisk on the Azov Sea in 1974, and the existing issues of Nomer were confiscated by the police, they began to issue a new journal, Transponans (1979–86, 36 issues), this time in only five copies (the legal limit at the time) that gradually grew in size and elaborateness of means. Since the issues were all handmade, it was possible to vary and combine materials, use elaborate original collages, hand coloring, original sketches, unusually shaped and cutout pages, to spectacular effect. Contributors to the journal included a wide range of contemporary avant-gardists, such as Dmitry Prigov, Genrikh Sapgir, A. Nik, Igor Bakhterev (the last surviving member of the OBERIU group), Yuri Lederman, Anna Alchuk, and many others. Toward the end of its existence, the journal took on the unique shape of what Nikonova dubbed a “rea-structure,” in which groups of pages were cut in a variety of shapes, such as triangles, M’s, and squares within one issue. While a certain genetic link to the primitivism and ZAUM of Cubo-Futurism is evident in many of their products, the group has nevertheless also created a large body of fresh and unprecedently inventive poetry, visual art, theater pieces, handmade bookworks, mixed media, and intermedia works under rather difficult circumstances.

—Gerald Janecek

“Transgressive”

(1980s)

Not avant-garde.

Just socially and morally challenging when it first appears (though probably not for long) and thus sometimes opportunistically dubbed “avant-garde.”

Typically such art is not difficult, which is to say that it’s easily made and easily understood.

Transition

(1927–38)

The most distinguished avant-garde magazine of its time, it was founded by EUGENE J OLAS, a polylingual American long resident in Paris. In its pages appeared early texts by SAMUEL B ECKETT, BOB B ROWN, and GERTRUDE S TEIN; reproductions or pictures of art by ALEXANDER C ALDER, MAN R AY, CONSTANTIN B RANCUSI, L. MOHOLY -N AGY, and PABLO P ICASSO; and even musical scores by AARON COPLAND and HENRY C OWELL (in a departure distinguishing it from other literary-art magazines before or since). Transition also sponsored symposia on such questions as “Why Do Americans Live in Europe,” “Inquiry on the Malady of Language,” “Inquiry into the Spirit and Language of Night,” or the puzzling early versions of JAMES JOYCE’s Work in Progress (later published as FINNEGANS WAKE).

So strong has the aura of transition been that other literary and art magazines founded by Americans in Paris have tried to recapture it, with less ambition and, alas, less success. Complete tables of contents of all 27 issues appear in 44 pages of the Dugald McMillan history. Around the year 2000 I was given bound copies of the complete run by the widow of a colleague who had received it from his favorite professor, so treasured are its issues. Three different book anthologies selecting from its pages have appeared.

Trnka, Jiří

(24 February 1912–30 December 1969)

Having created a puppet theater before World War II, Trnka set up in 1945 a film studio in Prague that specialized in puppet animation, which depends not upon drawings in sequence but on the movement of three-dimensional figures on a field. Unlike American animators, who were restricted to short films, Trnka founded his reputation on a feature, Špaliček/The Czech Year (1947). His principal achievement is an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Sen noci svatojánské) (1959) . Ruka/The Hand (1965) is a parable about the role of the artist under Communist totalitarianism.

Truck, Fred

(6 September 1946; b. Frederick John Allender)

Born in Iowa, where he still lives, Truck produced a chapbook of hieroglyphic VISUAL POETRY, Tangerine Universe in 3 Refrains (1975), in addition to Loops!! (1978), an edition of fifteen jars, each containing a Mobius strip, among other unusual literary objects. An early user of desktop computers, Truck began publishing his Catalog of the Des Moines Festival of the Avant-Garde Invites You to Show (without really being there) (1979, 1982, 1984) out of his house. George Maciunas, FIuxus, and the Face of Time (1984) he describes as “a graphically indexed study of Maciunas’s work,” which he printed on two long, continuous sheets of computer paper.

In 1985 Truck cofounded the Art Com Electronic Network, an early “electronic publishing medium uniting menu-driven magazines, a bulletin board service for performances and discussion of art,” for computer-modem-assisted artists hooked into the WELL, a national arts network. In continual contact with other artists similarly advanced, Truck from 1986 through 1991 worked on “an artificially intelligent art work, ArtEngine, which applies heuristics to graphics and text analysis.” His book Archaeopteryx (1992) has “designs for an artist’s flight simulator based on LEONARDO DA VINCI’s flying machine, which flies in visual reality.”

Bottega (1995) was probably the first CD-ROM produced by an artist in America. Designed for a Macintosh computer with “8 megabytes of RAM and a 640 × 480 × 256 color monitor,” it became inoperable when Apple upgraded the Macintosh operating system from 7.Ox to System 8. “Unfortunately, nothing can be done about this except a complete rewrite,” Truck wrote me at the end of 1998,

and I have since moved on to other things, motivated in no small part by the fact that digital art has a life expectancy of about 6 weeks due to the constant shifting of operating standards. My new work is focused on output that cannot be affected by changes in the hardware or operating system software. See www.fredtruck.com.

Milk Bottle Reliquary is a compendium of all his sculptures since 1998, both real and virtual (www.fredtruck.com/reliquary/). Truck has become, in short, the epitome of the advanced literary-computer artist, more experienced and better prepared than most to work into the 21st century.

Tsai, Wen-Ying

(13 October 1928–2 January 2013)

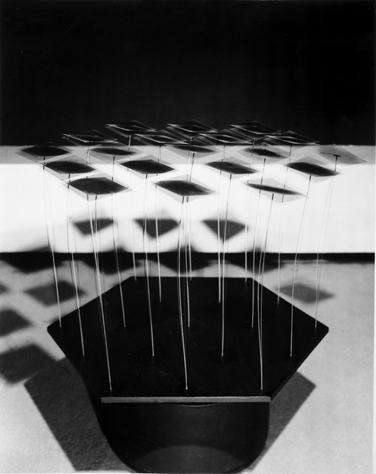

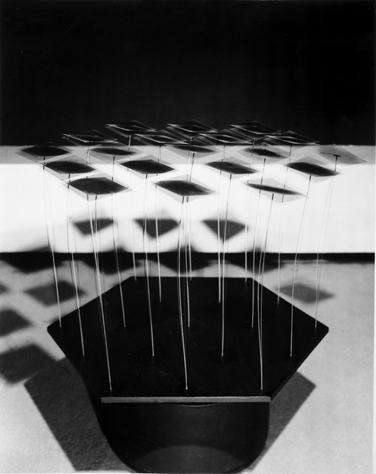

Tsai called his innovative work Tsaibernetic Sculptures (in a play on “CYBERNETIC”), which became his generic term for nearly one hundred unique objects that are similar in their operations but different in measurements and details. Born in China, trained at American colleges in engineering, which qualified him for years of work as a project manager in the construction industry, Tsai deduced in the 1960s that he could combine engineering with his painterly interests, producing sterling examples of avant-garde technological art. Influenced by an USCO exhibition in 1966, he used a flickering STROBE LIGHT that was aimed at shiny flexible rods with tops the size of bottle caps. Thanks to a motorized base, these rods could shake at variable speeds. The strobe light, flickering at a slightly different frequency, caught these vibrating rods in a succession of striking postures. Because the result was the anthropomorphic illusion of dancing, he transformed a firm material, steel, to look as though it had lost its rigidity

One improvement in the evolution of this genre was the ability to change the flickering speed of the strobe in response to either sounds in the surrounding space or the spectator’s proximity to a sensing device in the sculptures themselves, making them a pioneering example of responsive or cybernetic art (which I take to be technically more advanced than artistic machines that move autonomously). Another later development was making the upright rods out of fiberglass, rather than stainless steel. Though no two

of these Tsai sculptures are identical, they resemble one another much like siblings in a family that, at last count, is still growing.

Figure 19 Wen-Ying Tsai Square Tops, 1967. Stainless steel rods with aluminum squares on plywood plate, electric motor, stroboscopic light, and electronic audio feedback control.

Of Tsai’s other KINETIC sculptures, Upwards-Falling Fountain (1979) is particularly impressive, creating an illusion that must be seen to be believed. As the water falling from a vibrating showerhead is illuminated by a strobe, the droplets are caught dancing in response to sound; at certain strobe speeds, the droplets appear to be moving upwards, violating all rules of gravity. Living Fountain (1980–88) is a yet larger water sculpture, incorporating a showerhead 3 feet in diameter, plus three concentric circles of water jets, all installed above a basin 12 feet by 16 feet. Here the strobe is designed to respond to combinations of changes in audible music, random sensors, audio feedback controls, and a computer program.

Tu M’

(1918)

One measure of Marcel Duchamp’s genius is that even his initially off-hand works can be esthetically loaded. When his principal early patron, KATHERINE S. DREIER, asked in 1918 for a painting to hang above a bookcase, Duchamp provided his last canvas, over 2 feet high, nearly 10 feet wide, with a curious collection of disparate images. In his remarkably sensible Duchamp (1986), the French critic Jean-Christophe Bially (1949) writes:

The tentativeness of the title alone (Tu m’…, which looks automatically in French as the beginning of “you bore me”) betrays his lack of enthusiasm for the medium. Even so, with that consistency of purpose that we have come to expect to from him, he made use of the opportunity to try out a number of ideas relevant to his concerns at the time. The painting contains several different elements: shadows of Readymades, a trompe-l’oeil painted tear in the canvas held together by real safety-pins; various approaches to supplying the illusion of volume, both by the superimpositions of layers of colour and by the inclusion of a real bottle brush projecting at right angles from the painted surface. Tu m’ became an anthology of Duchamp’s capabilities.

The theme of this summary is that even such a modest work demonstrates esthetic intelligence (which differs from scholarly intelligence) that only an intelligently original artist can show.

Tucker, William G.

(28 February 1935)

One of the New Generation British sculptors of the early 1960s, Tucker presented sculptures not much different from those of his contemporaries, but he accompanied them with an intellectual program of surprising rigor. In his writings, Tucker located the significance of sculpture in its condition of being an object – in its stable and unchanging nature. In essence, sculpture is the fixed point in a turning world. Despite the cogency of Tucker’s thinking, his early works added little to the ground that was already being covered by PHILIP K ING. In the middle of the 1980s, Tucker turned to a style completely different from that of his previous efforts, and far more his own. Tucker began modeling by hand large and ponderous masses that look half like nearly formless lava boulders and half like human figures committing heroic gestures. In their craggy appearance, they harken back to the rough surfaces of Alberto Giacometti (1901–66) and GERMAINE R ICHIER. But unlike his predecessors, Tucker walks the line between the formed and the formless, creating shapes that seem as much the byproducts of geological forces as human images produced by a human being.

—Mark Daniel Cohen

Turrell, James

(6 May 1943)

The deepest truth of his most remarkable career, considering five decades of it, was that he knew from the beginning that his medium would be light. He didn’t discover light after a career of exhibiting objects or a period of theorizing. His first exhibition, in 1967, just two years after his graduation from college, consisted entirely of projections within a museum space. He then created, in his own Southern California studio, a series of light-based installations by cutting slits into the walls and ceiling to let sunlight sweep through his space in various configurations, as he used lenses to refract it strategically.

The first Turrell work I saw was Laar (1980). On the far side of a darkened room appeared to be a large, gray monochromic painting. As I moved closer, it retained that identity, its surface shimmering, much as good monochromic painting sometimes does. Only when I was literally on top of the work, close enough to bump my head into it, did I discover that, surprise, what looked like a monochromic rectangle is really a hole in the wall – or, to be more precise, an open window into a three-dimensional space filled with grayish light. If only to accentuate the illusion of a palpably different world, I could feel that the air behind the aperture had a perceptually different weight – heavier to my extended hand. In a later variation, Daygo (1990), shown at the Gladstone Gallery in New York in 1990, I stuck my head through the rectangle and noticed purplish light fixtures that were otherwise hidden from me. In either case, the effect was magical, the illusion of palpable nothing, really, is an extraordinary creation.

For decades, Turrell has worked in remote northern Arizona on transforming a volcanic crater into a celestial observatory. The “Roden Crater Project,” as he calls it, should be a masterpiece. However, until it is complete, as well as more popularly accessible, my Turrell nomination for the contemporary canon would be Meeting, as installed in 1986 at PS (Public School) 1 in Long Island City. Viewers are asked to come no earlier than one hour before sunset and to stay no later than an hour after sunset. They are ushered into a former classroom, perhaps 20 feet square. Most of the ceiling has been cut away into a smaller rectangle, leaving the sky exposed. (It looked like clear glass to me until I felt the temperature change.) Though benches are run along the walls, it is perhaps more comfortable to lie on the floor rug, looking skyward. Along the top of the benches runs a track, behind which is a low level of orange light, emerging from tungsten filaments of thin, clear, meter-long, 150 watt Osram bulbs. (Having no visible function before sunset, these lamps make a crucial contribution to the subsequent illusion.)

What Turrell realized in his Meeting is framing the sunsetting sky, making its slow metamorphosis visible, in an unprecedented a time-dependent visual experience, literally a nature-based theater, that proceeds apart from human intervention. The sky looks familiar until it begins to turn dark. Lying in the middle of the floor, I saw the sky pass through a deep blue reminiscent of YVES K LEIN. Above me developed, literally out of nowhere, the shape of a pyramid, extending into the sky; and as the sky got darker, the apex of the navy blue pyramid slowly descended down into the space. Eventually it vanished, as the square became a flat, dark gray expanse, looking like nothing else as much as a James Turrell wall “painting,” before turning a deep uninflected black that looked less like the open sky than a solid ceiling.

Now, I know as well as the next New Yorker that the sky here is never black; there is too much ambient light. What made the sky appear black was the low level of internal illumination mentioned before. (You can see the same illusion at an open-air baseball night game where, because of all the lights shining down onto the field, the sky likewise looks black.) I returned on another day that was cloudier than before, to see textures different from those I remembered. On the simplest level, what Turrell does is manipulate the natural changing colors of the sky, first through the frame that requires you to look only upwards, and then with thoughtful internal illumination that redefines its hues.

What is also remarkable is how much intellectual resonance the work carries to a wealth of contemporary esthetic issues, such as illusion/anti-illusion, painting/theater, unprecedentedly subtle perception, the use of “found objects” (in this case, natural light), and conceptualism (bestowing meaning on apparent nothing), all the while transcending all of them. I personally thought of John Cage’s 4′33″, his “noise piece,” in which he puts a frame around all the miscellaneous inadvertent sounds that happen to be in the concert hall for that duration, much as Turrell frames unintentional developments in the sky.

Meeting is essentially theatrical in that its PERFORMANCE must be experienced over a requisite amount of time; no passing glance, as well as no single photograph, would be appropriate. Indeed, though Meeting could have been realized technically prior to the 1950s, there was no esthetic foundation for it prior to then. Another likely Turrell masterpiece I’ve not experienced firsthand is in West Cork, Ireland: The Sky Garden at Liss Art Country House Estate (1992), which reportedly has unusual acoustics as well.

His work is commonly connected to that of ROBERT IRWIN, fifteen years older, likewise hailing from Southern California, as both feature light in their art. However, whereas the older artist uses objects to shape light, Turrell simply frames light. Esthetic geniuses both are.

Tutuola, Amos

(20 June 1920–8 June 1997)

Nigeria’s most original novelist was a thinly educated war veteran who wrote English as only a Nigerian could. “I was a palm-wine drinkard since I was a boy of ten years of age,” Tutuola’s first book begins. “I had no other work more than to drink palm-wine in my life. In those days we did not know other money, except COWRIES, so that everything was very cheap, and my father was the richest man in our town.” And his language gets only more original. Because Tutuola reportedly grew up speaking Yoruba, he makes authentic errors of English grammar and spelling on every page; yet his several novels have clear plots, usually about a protagonist with (or with access to) supernatural powers, who suffers awesome hardships before accomplishing his mission.

One scholar reports that educated Nigerians

were extremely angry that such an unschooled author should receive so much praise and publicity abroad, for they recognized his borrowings, disapproved of his bad grammar, and suspected he was being lionized by condescending racists who had a clear political motive for choosing to continue to regard Africans as backward and childlike primitives.

Even with modest success, authentically original artists will always be attacked for some purported deficiency or another.

Twelve-Tone Music

See SERIAL MUSIC.

2001

(1968)

Stanley Kubrick (1928–99) was an intelligent and morally sensitive filmmaker who, in the heady wake of the success of his second-best early film, Dr Strangelove (1964), made this classic for CINEMA S COPE projection. Because 2001 is not often publicly available in that form, we tend to forget how it filled wide, encompassing screens with memorable moving images, all of which had an otherworldly quality: the wholly abstract, richly textured, and incomparably spectacular eight-minute “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite” (as the clumsy subtitle announces the sequence); the stewardess performing her routine duties in the gravity-less spaceship; and the opening scenes in the space vehicle (which are filled with more arresting details than the eye can comfortably assimilate). Rather than focusing our attention, the movie consistently drives our eyes to the very edges of the screen (much like another CinemaScope masterpiece, David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, 1962), in the course of emphasizing the visual over the aural.

Over two hours long, 2001 has only forty-six minutes of dialogue, making it in large part, paradoxically, a mostly silent film for the age of wide-screen color, incidentally placing it in the great avant-garde tradition of mixing the archaic with the new as a way of eschewing expected conventions. Indicatively, 2001 ends with several minutes of images-without-words, rather than, say, an exchange of lines. The central image of the monolith, whose initial mysteriousness is reminiscent of the whale in HERMAN MELVILLE’s Moby-Dick, becomes a symbol whose final meaning is revealed as literally the sum of the movie itself, putting a seal of accumulated perception upon the preceding action.

One is surprised to recall how many intelligent people, including prominent reviewers, disliked 2001 at the beginning, and how many parents were less enthusiastic than their children. “I ought not to have found this surprising,” wrote the physicist Freeman Dyson (1923), “for I am myself of the generation that was bowled over by Disney’s FANTASIA thirty years ago, while our sophisticated elders complained in vain about our shocking bad taste.” Even though 2001 alludes to Georges Méliès’s Trip to the Moon (1902), there has not been anything like it since, whether for small screens or large; it’s too bad that the large-screen motion-picture theaters capable of showing it best (and, say, Lawrence of Arabia) are by now nearly extinct.

Twombly, CY

(25 April 1928–5 July 2011; b. Edwin Parker Twomby, Jr.)

As an eccentric American painter emerging in the wake of ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM but preceding MINIMAL art, he produced with paint, crayon, and sometimes even pencil many large visual paintings and drawings with a scattering of delicate marks, some of them suggesting calligraphy, that at their best evoke invisible spiritual realities. His work gains from echoing ancient graffiti often found in holy places. As nobody else’s visual art looks like Twombly’s, several paintings gathered together within a single room can realize an impact greater than the sum of its parts. The British critic David Sylvester (1924–2001) once judged that their delicacies are best seen under natural light.

Typewriter

This 19th-century invention changed writing, not only when authors such as Henry James (1843–1916) dictated to secretaries who transcribed on the new machine, but when writers typed themselves. In the mid-20th century came electric typewriters that enabled writers to enter more words quicker, leading many to compose longer sentences. (I know; I can remember when I first got mine.)

Typewriter Literature

(c. 1940s)

Poets such as E. E. CUMMINGS and CHARLES OLSON used the typewriter to create expressive alternative spacing between words. To the latter writer, “It is the advantage of the typewriter that, due to its rigidity and space precisions, it can, for a poet, indicate exactly the breath, the pauses, the suspensions even of syllables, the juxtaposition even of parts of phrases.” Composing literature directly on the typewriter also enabled authors to exploit its capacity for regularizing inscriptions and, better yet, for giving publishers camera-ready pages to print, rather than allowing typesetters to falsify the spacing and other design dimensions. Though certain typewriters presaged computers in permitting closer spacing of lines and/or letters, the creation of expressive shapes was possible on all typewriters. Among those making poems in this way were two older poets with conservative tastes, William Jay Smith (1918–2015) and May Swenson (1913–89), in both cases briefly, and then younger poets, among them DOM S YLVESTER H OUÉDARD and KARL K EMPTON. Robert Caldwell (1946) founded his periodical Typewriter (1971) on the reasonable assumption that such writing deserved an outlet of its own. More interesting, to my mind, were the novels composed on the typewriter and printed directly from a typescript: the original edition of RAYMOND F EDERMAN’s Double or Nothing (1971), Willard Bain’s Informed Sources (1969), and especially Guy Gravenson’s brilliant The Sweetmeat Saga (1971), in which fragments are splayed rectilin-early across the manuscript page. Marvin and Ruth Sackner, the most ambitious American collectors of visual poetry, produced an anthology The Art of Typewriting (2015).

Since the early 1980s, authors have used home computers to produce camera-ready pages that approach (but don’t quite equal, especially in the lack of subtle kerning) the appearance of professional typesetting.

Tzara, Tristan

(16 April 1896–25 December 1963; b. Samuel or Sami Rosenstock)

A Rumanian Jew who left his native country at nineteen, Tzara almost always wrote in French, initially as a cofounder of Zurich DADA in 1917 and then as a SURREALIST in Paris from 1920 to 34, when A NDRÉ BRETON ousted him from the club for his deviant radicalism. He remains the only poet/poet to make substantial contributions to both French movements. The critic Marc Dachy credits Tzara with giving

French poetry a new impetus, a sudden acceleration. He took unpunctuated free verse, inherited in part from GUILLAUME A POLLINAIRE and BLAISE C ENDRARS, and transformed it into an extraordinarily powerful instrument. By exciting the latent energies in language he created an extreme poetry filled with vertiginously polysemic meanings and the novel rhythms of substantives flashing by like telephone poles seen from a speeding car.

Apart from this achievement, Tzara wrote a great long poem, L’Homme approximatif (1931, The Approximate Man), and a classic proto - CONCEPTUAL manifesto in the form of a poem:

To make a Dadaist poem/ Take a newspaper./ Take a pair of scissors./ Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem./ Cut out the article./ Then cut out each of the words that make up this article & put them in a bag./ Shake it gently./ Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag./ Copy conscientiously./ The poem will be like you.

In his autobiography the American composer OTTO LEUNING recalls of Tzara: “He used bells, drums, whistles, and cowbells, beating the table to punctuate his declamations and to invite the audience to participate in his performance. He would curse, sigh, yodel, and shriek when the spirit moved him.”

This model of the Jewish émigré avant-garde literary activist, working in a country and language both not his own, has inspired certain later poets similarly situated.