Chapter 18

The world is my oyster

Atlassian is Atlassian because its flagship product, Jira, is the industry-standard, market-leading product globally.

Jira dominates the market in the USA, the UK and Germany – and, consequently, in Australia. When (like Jira) your product solves a generic problem, you have no choice but to be a global player.

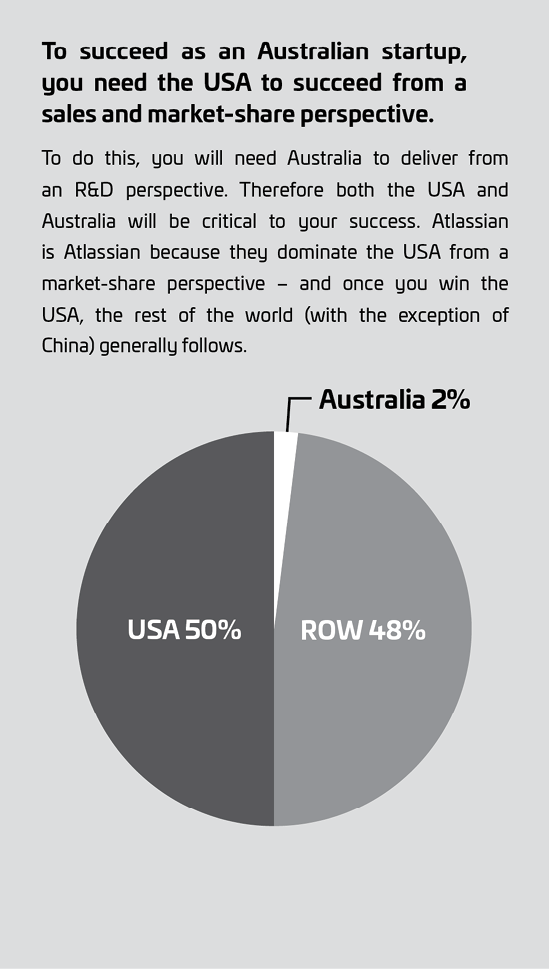

Whether we like it or not, Australia only represents approximately 2 per cent of the global market, while the USA represents about 50 per cent of the world market for technology products and services. In order to win, you have to win in the USA – and then the rest of the world, maybe with the exception of China, will fall like dominoes. Every product that is the market leader in the USA is generally the market leader in Singapore, France, Brazil and Australia. So, if the problem that your product or service solves is generic, it’s no good just being the King or Queen of Australia. From the outset, you need to be thinking about how you’re going to conquer the world.

Let’s assume that the total addressable market (TAM) for your product is $100 million. Say that your startup, OziSoftware, wins the entire Australian market. Your total sales will be about $2 million. In the meantime, your US competitor, YankeeSoft, is generating $50 million in sales. You put 40 per cent of your revenues into R&D, and YankeeSoft put 20 per cent of theirs into R&D. You’re spending $800,000 compared with YankeeSoft’s $10 million. No matter how good your engineers are, you’re going to lose. YankeeSoft will out-innovate you, out-market you and out-sell you and soon your home market will be gone. They will be in the Gartner Magic Quadrant and selling to the Fortune 500. The more customers, the more validation, the better the roadmap and the easier it will be to sell.

Australia is a great base in which to build software. Our engineers are as good as any in the world. And we have some customers that are large enough to help provide a critical level of initial validation and vital feedback. If your product is good enough for a big Australian bank, it will be good enough for a big US bank; if you’re good enough for Telstra, you will be good enough for Sprint.

Having said that, some products or services can succeed by specifically addressing the Australian market. MYOB built a great company just by selling accounting software in Australia (although they did have a shot at overseas expansion), and companies like SEEK, realestate.com and carsales.com could easily have built extremely successful companies just operating in Australia – although, for growth, they have all pursued global opportunities. But the great Australian software success stories, like Atlassian, Canva, WiseTech, Appen, Aconex, CultureAmp and Safety Culture (and the others that will follow), could never have achieved what they have, just by selling into a market that represents only 2 per cent of the total addressable market. It’s simply a numbers game.

How do I know all this? Because, unfortunately, I am writing with experience on my side. After I left Com Tech, I mentored the founder of an awesome company called Holly. I actually became the executive chairman and I learnt a lot about adding value to a founder and CEO in this capacity – it defined my future career. If you were to look at the pitch deck for Holly today, you would think it must be the business plan for Siri or Alexa. Holly was a speech-recognition platform. Holly, what will the weather be like tomorrow? Holly, what is the stock price of Apple? Nothing mind-blowing today, but this was in 2000. We were going to be the world’s first voice-search portal. After the dot-com crash, we had to pivot the business to become a software-based interactive voice response (IVR) platform. We started winning some great accounts in Australia: all three Australian telcos, Telstra, Optus and Vodafone, became referenceable customers and they still use Holly today.

Unfortunately, the Holly of the USA was a company called VoiceGenie. They were winning big in the United States while we were winning in Australia. The USA is 13 times larger than Australia in terms of population size, so VoiceGenie were generating far more sales and winning far more customers than we were. We waited too long to launch there and we paid the price. When we did enter the USA, it was almost impossible to displace VoiceGenie, even with a far superior product. We eventually exited to one of our customers in the USA – West Interactive.

I was really proud of what we achieved at Holly. When I arrived, the culture was toxic – the two founders were killing each other, the software didn’t work and we were running out of cash. When we sold, we had one of the best teams that I have ever been privileged to work with (I had fired one of the founders), we were making money, and the software was being used by some of the world’s largest telcos. My big regret is that we didn’t move fast enough to execute in the USA. It was an expensive lesson to learn – Holly could have dominated the market, had we been bold enough to move more quickly. We were selling a generic software-based IVR platform, and VoiceGenie beat us to it. We missed the boat and were unable to maximise the potential of the opportunity.

While Australia may only represent 2 per cent of sales, it will probably represent 100 per cent of your R&D, at least initially – so it’s crucial to have strong leadership in Australia, especially if the founder relocates. Your startup needs Australia to be strong in order for the USA to be strong, while the USA needs to be strong for Australia to be strong. That is, the USA needs to sell lots of product in order to win the lion’s share of the 50 per cent of the total addressable market, while Australia needs to deliver, innovate and build a reliable product. Get that right and you could just be the next great company to emerge from Australia.

• • •