On his arrival in Washington, Sherman reported at once to Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, who was still the general in chief of the army. There he found the old warhorse, now seventy-five years old, working around the clock in an effort to create an army out of the collection of volunteer regiments coming in from the states. On the insistence of Simon Cameron, the army would be made up almost entirely of volunteer regiments known by their state designations, such as the 71st Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment. This decision had been made much to the displeasure of the generals, most of whom were regulars.

The meeting with Scott brought on one small disappointment: Sherman had been expecting to leave Washington at once to begin recruiting his regiment at St. Louis, but Scott had other ideas. Sherman was to remain in his own office for a time to serve as the army’s inspector general. The general insisted that Sherman’s lieutenant colonel, in Missouri, could tend to the business of recruiting the regiment.

Sherman soon discovered, however, that his job as inspector general had one pleasing aspect: It allowed him a chance to travel around and get a feel for the overall situation in the eastern theater. Events were happening rapidly. Scott, Sherman soon learned, was organizing the troops around Washington into two separate armies. One was located directly across the Potomac from Washington, under the command of a newly appointed brigadier general, Irvin McDowell. The other, located farther west at Hagerstown, Maryland, was under the command of Major General Robert E. Patterson, who had been a prominent general in the Mexican War thirteen years earlier.

Neither was a good choice. McDowell, who owed his position partly to his friendship with Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, had neither sought nor desired the command. His career in the army had always involved administration, and he had never commanded a troop unit of any size. His counterpart, Patterson, who had always been mediocre, was advancing in age. While not doddering, he was lacking in the energy necessary for arduous duty. But as of that moment, as Sherman observed, the authorities in Washington, with the exception of Scott, were convinced that this would be a short war, with the South giving up without much of a fight. The tragedy that awaited both sections of the country was not yet foreseen. Sherman visited his brother John, who had temporarily left his seat in the Senate to serve as a volunteer aide to General Patterson. All was optimism.

That hubris would cost the nation dearly. Scott, one of our greatest generals, was now too old and overweight to take the field in person. He was, however, a military student, and he bore no illusions that the people of the South would succumb easily. In this realization, Scott and Sherman were remarkably close. The Mississippi River, they contended, would be critical in the coming conflict. The Union would have to occupy it for its full length, isolating the cotton states from Texas and Arkansas, cutting off resupply from the West.

The trouble with Scott’s plan, scornfully termed the “Anaconda Plan” by its critics, was that it would take months, even years, to put into effect. The temper of the times called for immediate action: “On to Richmond,” cried the New York Tribune. Abraham Lincoln, much as he respected the views of his general in chief, could not resist the pressure of public opinion. He ordered McDowell and Patterson to move forward against Beauregard’s army at Manassas on July 16, 1861.

—

Sherman was destined to be part of this offensive. At the last minute, just before McDowell marched off, he was placed in command of a brigade. It was not what he would have preferred.* All of the units, with the exception of the 3d Artillery, were volunteers. Sherman took a jaundiced but philosophical view of his command. He later wrote, “We had good organization and good men but no cohesion, no real discipline, no respect for authority, and no real knowledge of war.”1 He took solace in reminding himself, however, that the Confederates were in no better condition than the Union troops.

Sherman’s brigade was assigned to a division commanded by Brigadier General Daniel Tyler, basically a good man but unqualified to be a high commander. A West Point graduate from the class of 1819, he had resigned his commission in 1834 to pursue a successful career in business. Now, at the age of sixty-two, he was going into the field after an absence from the army of twenty-seven years. He had reentered service commanding a volunteer Connecticut regiment, but so desperate were Lincoln and Scott for men with military backgrounds that he had been given a division soon after.2 The division consisted of four brigades—Sherman’s, Erasmus Keyes’s, Robert Schenck’s, and Israel Richardson’s.

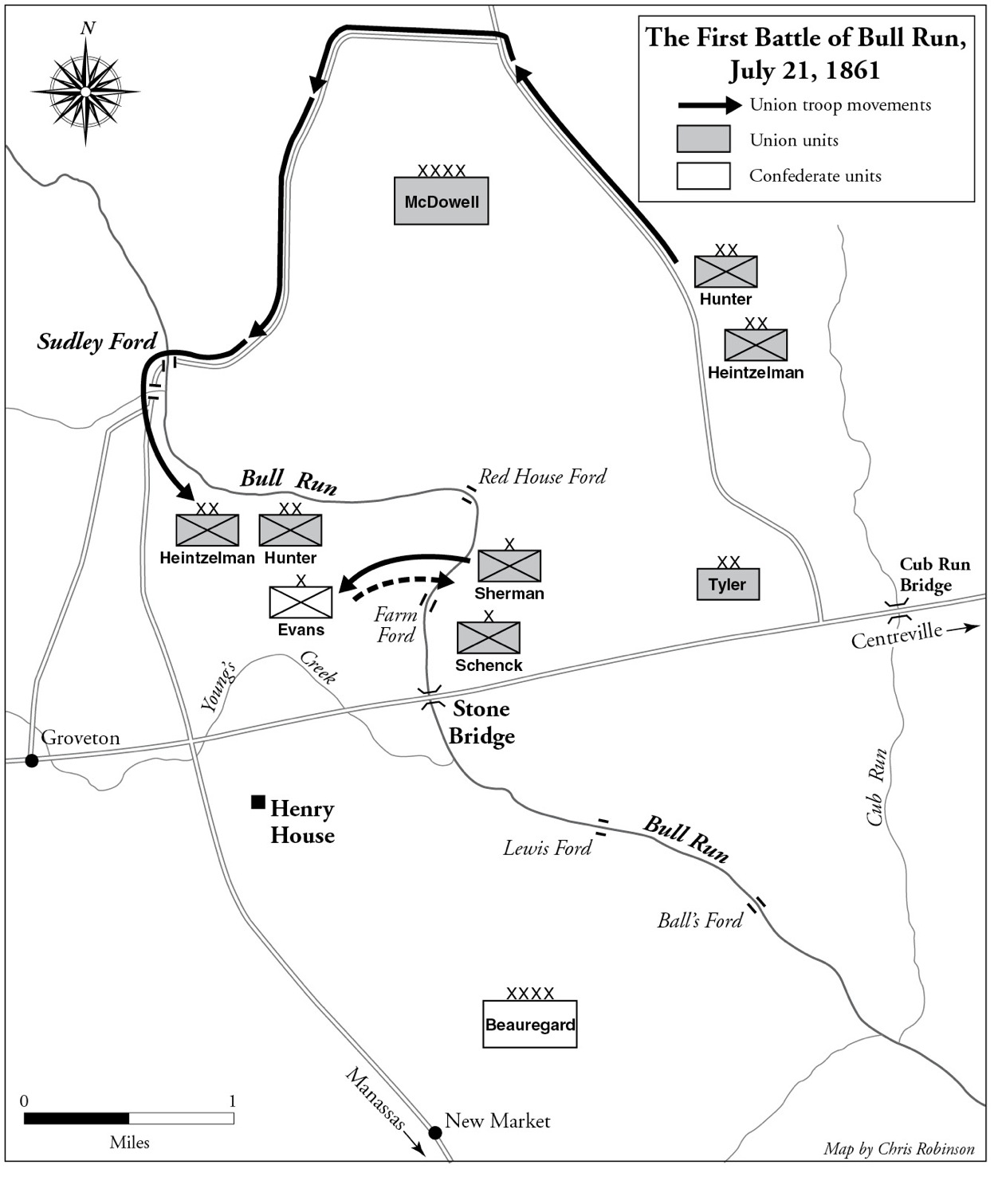

As of the morning of July 21, both sides were deployed behind Bull Run, a stream that ran about halfway between Centreville and Manassas. Both sides planned to attack. McDowell and Confederate general Beauregard were each concentrating his force on his right wing, planning to envelop the other one’s left. Beauregard, with Brigadier General Joseph Johnston having joined him after eluding Patterson in the Shenandoah, was based on Manassas Junction. McDowell, on the Warrenton Pike, intended to send Tyler across Bull Run by way of the Stone Bridge, largely as a demonstration. He planned to move the bulk of his forces, two divisions under brigadier generals Samuel P. Heintzelman and David Hunter, northward to cross Bull Run at Sudley Springs and attack southward, rolling up Beauregard’s left. Both McDowell’s and Beauregard’s plans were good, but McDowell struck first. Beauregard, realizing his plight, moved northward across Henry House Hill to meet him.

Of Tyler’s three brigades, he sent Schenck’s directly to the Stone Bridge. Keyes was to march northward behind Hunter’s division, and Sherman was to follow Schenck and take position at a point behind Bull Run about a mile north of Stone Bridge.

Sherman left Centreville at two thirty a.m. on the morning of July 21, arriving at his destination around six a.m. He deployed his four regiments along the riverbank and waited. During the morning Hunter’s division, bound for Sudley Springs on the north, began its northern movement, followed by Heintzelman’s. The road leading to Sudley Springs was no highway; it was a rough trail. Sherman knew that it would take a long time for the two divisions to get into position.

Sometime during the morning a small but significant incident occurred. A Confederate officer on horseback crossed Bull Run to the Union side, rode toward Sherman’s position, and then, staying out of musket range, shouted curses and insults at the Yankees. Then, apparently satisfied, he returned back across the stream. Sherman’s sharp eye followed him; he carefully noted the place where the hotheaded rebel horseman had forded the stream.

It was midmorning before Sherman detected the sound of battle off to the right, where he correctly surmised that Hunter’s division had made contact with the Confederates. He had no way of knowing that Hunter was being faced by only a single Confederate brigade commanded by an irascible, hard-drinking member of the West Point class of 1848, Nathaniel “Shanks” Evans.*

At about two p.m. General Tyler arrived at Sherman’s position. Hunter and Heintzelman, he said, were hard-pressed, and it might be necessary to send the 69th New York across Bull Run to assist. A short time later, Tyler ordered Sherman to move his entire brigade across Bull Run; Hunter needed assistance. Sherman then recalled the incident of the morning, when the lone Confederate had forded the stream, and he moved his brigade to that spot. Without difficulty, he managed to send his infantry over, but an escarpment on the far side was too steep for his artillery. Sherman reluctantly instructed Captain Romeyn B. Ayres, commanding the 3d Artillery, to take position on the east bank and fire at whatever targets he could find on the west bank. Sherman then marched to the sound of the guns.

Sherman, as with other participants in this battle, had a special caution to observe. The color of a unit’s uniform was not a reliable way of ascertaining whether a unit was Union or Confederate. Some of the Confederates, not yet issued gray uniforms, still wore blue. One of Sherman’s volunteer regiments wore gray. He therefore had to make a special show of flags as he approached Hunter’s men on the plateau across the stream. This accomplished, he sent his men into battle.

The terrain in Sherman’s area was extremely rough. It was so restricted as to render it impossible to commit all three of his regiments at once. He was therefore forced to commit them one at a time. Each went forward in good order, considering their lack of training, and in turn they were chewed up and had to withdraw. The fighting was hard. Sherman’s action was not part of the more noted battle to the south on Henry House Hill, but it was just as fierce.

Finally, Sherman’s men decided on their own that they had had enough. Despite their commander’s urgings to stay in the fight, each regiment began making its way slowly and deliberately to the rear. There was as yet no panic, but the move was inexorable. Sherman, a realist, soon concluded that these men had had all the fighting they were going to do that day. He therefore guided them back to the ford they had originally crossed. Late in the day they were safely on the east side of the stream.

—

The fighting done by Sherman’s brigade was obviously only a small part of the story of Bull Run. Furthermore, the actual fighting was not the most memorable aspect of the day’s events. The worst was the panic that soon developed once the Union soldiers had escaped back across Bull Run. Sherman kept his men in better order than did most brigade commanders; in fact, his performance was noticed.* At Centreville, Sherman encountered McDowell, who was still hoping to make a stand at that position. But it was too late; the men could not be stopped. The rout continued through the night, led by the carriages of civilian spectators who had come out from Washington. Sherman himself did not reach his former headquarters, Camp Corcoran, until noon the next day, July 22.

Sherman’s brigade had lost heavily. In his official report, submitted on July 25, he listed his total casualties (out of a brigade of 3,500) as 609, of which 111 had been killed. More than twice that number were missing. The casualties had been particularly heavy among the officers. He mentioned Lieutenant Colonel Haggerty (killed), Colonel Cameron (mortally wounded), and Colonel Corcoran (missing).3

—

Even though Sherman had performed well, he was in a black depression. Never mind that he had predicted a poor performance from his volunteer troops. Never mind also that his good performance had been noticed by his superiors. Such matters were trivial compared to defeat. On July 24 he wrote Ellen, principally to assure her that he had survived the battle. Then, on the twenty-eighth, he wrote her a long account, which is more lucid than the official report he had submitted to General Tyler. In particular he was angry about the pursuit:

Here [Centreville] I suppose we should assemble in some order the confused masses and try to stem the tide. Indeed I saw but little evidence of being pursued, though once or twice their cavalry interposed themselves between us and our rear. I had read of retreats before, having seen the noise and confusion of crowds of men at fires and shipwrecks, but nothing like this. It was as disgraceful as words can portray, but I doubt that volunteers from any quarter could do better. Each private thinks for himself. If he wants to go for water, he asks leave of no one. . . . No curse could be greater than invasion by a volunteer army. No Goths or Vandals had less respect for the lives and property of friends and foes, and henceforth we ought never to hope for any friends in Virginia.4

—

Despite this anguish, Sherman had other, immediate problems to deal with. Fort Corcoran was located on the Virginia side of the Potomac, but many of his troops did not consider the position strong enough and they continued to flee into Washington. Sherman recovered almost all of them.

As always Sherman was methodical in restoring order in his sector of the defense. He first consolidated his four regiments, bringing them as close together as possible. The 69th New York, their colonel still missing, returned to Fort Corcoran, and the 79th New York and the 2d Wisconsin were moved in closer to it. By the twenty-fifth of July, only a couple of days after reoccupying that position, Sherman was reasonably confident that he could defend against the Confederate attack that everyone presumed was inevitable. His success was duly noted.

It was not, however, an easy job. To restore a sense of discipline, Sherman drilled his men hard. To stem desertion he held three musters a day to ascertain how many men, if any, were missing. The men were not docile; so many wanted to leave camp that at one point Sherman unlimbered an artillery battery with a threat to blast some would-be deserters if they really tried to leave.

—

July 26, 1861, was a memorable day for the commander of the 3d Brigade. In the morning, just following reveille, Sherman noticed a few men from the 69th New York heading for a nearby drawbridge across the Potomac. As far as they were concerned, their three-month enlistment was up; they had, in fact, applied for discharge just before the move on Bull Run a week earlier. Among the departing group was a doughty captain who lightly asked the colonel whether there was anything he could do as a favor when he and his men reached New York.

Sherman bristled. In a positive manner he pointed out that he had signed no orders granting any leaves of absence. The captain reiterated the oft-repeated argument that since his unit’s time was up, his men were no longer soldiers; they needed no leave.

Sherman sensed a crisis. If he allowed these men to depart, he could soon be a colonel without a command. He therefore played his trump card. “Captain,” he later recalled saying, “this question of your term of service has been submitted to the rightful authority, and the decision has been published in orders. You are a soldier, and must submit to orders till you are properly discharged. If you attempt to leave without orders, it will be mutiny, and I will shoot you like a dog! Go back into the fort now, instantly, and don’t dare to leave without my consent.”5 In recalling the incident, Sherman was not certain whether or not his right hand was near a firearm, but in any event, the captain looked at him a long time and then obeyed his orders. The men scattered; none left.

The story did not quite end there. Later in the day, when Sherman was inspecting some installations down near the river, he was surprised to see a carriage being ferried across the river from Georgetown. The occupants of the carriage were unmistakable; they were President Abraham Lincoln and his secretary of state, William Seward. Sherman went down to meet them and asked whether their destination was his position. It was. Upon Sherman’s offer to provide him a guide, the president invited him to join the party and guide them himself.

As the carriage labored up the hill, Sherman was impressed by the depth of Lincoln’s feelings. Asked whether he wished to address the troops, Lincoln said he would very much like to. Sherman sent word ahead to assemble the troops of one regiment, but he had an earnest and unusual request: that Lincoln discourage the men from cheering. “I asked him,” Sherman later wrote, “to please discourage all cheering, noise, or any sort of confusion; that we had had enough of it before Bull Run to ruin any set of men, and that what we needed were cool, thoughtful, hard-fighting soldiers—no more hurrahing, no more humbug.” Perhaps Sherman was surprised by the good-humored way the president took this admonition from a colonel.6

By the time Lincoln’s carriage reached the first camp, he found the men drawn up in proper fashion. Lincoln stood up straight in his carriage to address them. Sherman was struck by the quality of his speech, later calling it “one of the neatest, best, and most feeling addresses I ever listened to.” At one point the men began to cheer, but Lincoln stopped them: “Don’t cheer, boys. I confess I rather like it myself, but Colonel Sherman here says it is not military; and I guess we had better defer to his opinion.” The president finished by promising that his soldiers would have everything they needed. Sherman considered the effect of the speech excellent.7

Lincoln was able to speak to only one regiment at a time, and the second one was the New York 69th. His talk was similar to the earlier one, but while it was in progress Sherman spied the captain he had threatened that morning working his way through the crowd, pale faced and tense. When the captain reached Lincoln’s side, he shouted, “Mr. President, I have a cause of grievance. This morning I went to speak to Colonel Sherman, and he threatened to shoot me.”

Lincoln paused before speaking; he looked at the captain and then looked at Sherman. Finally, he leaned way over and said in a loud stage whisper for all to hear, “Well, if I were you, and he threatened to shoot, I would not trust him, for I believe he would do it.”

The crowd laughed, and the captain disappeared in the crowd. When Sherman later explained the circumstances of the incident, the president was relieved. Lincoln’s support made Sherman’s task easier in the future, and he was happy when Seward remarked that the visit had been “the first bright moment they had experienced since the battle.”8

Lincoln’s visit did not, however, mean an end to the discontent in the army. Some discipline was enforced by sending regiments or parts of regiments to Fort Jefferson, in Florida. But the real solution to the problem came when the three-month men were sent home and were replaced by three-year volunteers. Sherman was reinforced and was able to move his line of defense out ahead of the ramparts at Fort Corcoran.

—

Sherman’s chagrin over the defeat at Bull Run was such that in spite of his pleasant encounter with President Lincoln, he expected to be cashiered. So did Heintzelman, Porter, and others. One evening, however, as the officers were gathered at Arlington House—a Virginia mansion converted into the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac—a message came in carrying a list naming several officers who were to be promoted to the grade of brigadier general.* Sherman was one. The officers scoffed at the idea, but it later turned out to be true.

General Irvin McDowell remained in command of the Army of the Potomac for a short while. From his headquarters at Arlington House, he organized his army and awaited the arrival of his replacement, Major General George B. McClellan. In due time, McClellan arrived and assumed command. Sherman felt his first doubts about the showy little engineer from Ohio. Instead of taking station with the army across the river at Arlington House, McClellan took a house in Washington and visited the army only occasionally. Sherman developed his first inkling that McClellan had political as well as military ambitions. Still, “Little Mac,” as McClellan was soon dubbed by his troops, was a good organizer, and soon the Army of the Potomac began to take shape.

Sherman did not have long to stay at Fort Corcoran, located along the Potomac River, just southwest of the nation’s capital. In the middle of August he received a note from Robert Anderson, former commander at Fort Sumter, now catapulted from the grade of major to that of brigadier general. Sherman was elated to read that Anderson was asking him to ride into the city to confer with him at the Willard Hotel. He readily agreed, and they joined a small group that included Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee.

Anderson had just been appointed to a newly organized command, the Department of the Cumberland, which consisted of Union forces in Kentucky and Tennessee. It was an important mission and an urgent one. The legislature of Kentucky was in session, and Anderson’s first challenge would be to convince that body to remain with the Union. The chances were good, and Union troops were being provided to protect the area from invasion by Confederate forces. To help him, Anderson had been authorized to select four assistants. Sherman’s name headed the list, which also included George H. Thomas,* Ambrose Burnside, and Don Carlos Buell, all four men destined for prominent roles in the war. Sherman readily agreed.

A couple of days later, Anderson and his newly appointed aides met personally with President Lincoln to discuss the mission. At that time, Sherman made a strange demand: He exacted a promise from the president that he would serve only in a subordinate capacity, not in a high command. Sherman had apparently not yet recovered from what he considered his own failure at Bull Run, and a realistic assessment of his own strengths and weaknesses was one of his most remarkable aptitudes. But he was also influenced by his contempt for volunteer soldiers. As he saw it, the first members of the Union high command would be sacrificial lambs. He did not want to be one of them. He would wait until the Union finally developed a trained army.

With some surprise, Lincoln agreed. “He promised,” Sherman later wrote, “making the jocular remark that his chief trouble was to find places for the too many generals who wanted to be at the head of affairs . . .”9 Orders were issued by General Scott on August 24, 1861. Sherman’s future service in the Civil War would be in the West, as he preferred.