In Grant, Sherman had found a man he could serve under with zest. They were personally compatible, and equally important, they shared extremely high standards. Sherman’s regard for Grant was lavish; Grant returned the admiration, though probably not quite so intensely. The outside world, even in the army, was as yet unaware of the extent to which Sherman’s efforts had contributed to Grant’s successes, and recognition of his worth would require further evidence. That evidence would soon be provided by Sherman’s role in the gigantic battle of Shiloh, or Pittsburg Landing.

Sherman saw Grant as a man who would fight, who would even ignore accepted rules. As an avid reader of military history, Sherman recalled a formula laid down by the iconic Napoleonic staff officer Baron Antoine-Henri Jomini. Jomini had pontificated that, in order to conduct a successful siege, the besieging force needed a strength five times that of the defender. Here, Sherman observed, Grant had invested Donelson with a force actually inferior to that of Floyd and Pillow.

Grant fully appreciated what Sherman had done in relieving him of the need to fret over his supplies and reinforcements during that action. But Sherman’s reward was more tangible than mere admiration: His command at Paducah was redesignated as a combat unit. He was now a brigadier general in command of a division, one of the six under Grant’s command.

Others, higher ranking and better-known, were given even greater kudos. The greatest credit was given to Halleck, whose Department of the Missouri was expanded to include Buell’s Army of the Ohio, with which Halleck had previously been on an equal status. Both Grant and Brigadier General Charles F. (C. F.) Smith, his second in command, were promoted to the grade of major general of volunteers. The Union was beginning to develop the team that would eventually bring victory. Oddly, at this point, they were all in the West.

Halleck’s star was now at its zenith. Not only had he been placed over his rival Buell, but he had been given credit for the fact that, with the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers closed, the Confederate commander, Albert S. Johnston, had been forced to evacuate Bowling Green on the Tennessee River and Nashville on the Cumberland. Johnston retained scattered positions,1 but the all-important fact was that Kentucky was now safe for the Union. Future battles east of the Mississippi River would be fought in West Tennessee and farther south.

Halleck now decided to concentrate his two armies, Buell’s and Grant’s, into one, over which he would assume personal command. With that powerful combined force, he hoped to drive south to the Gulf of Mexico. But arranging for that ambitious project would take some time, during which he intended to cut the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, which ran west–east from Columbus on the Mississippi River, through Corinth to Memphis and Richmond beyond. In a day when the road net was primitive, rivers and railroads were the critical means of delivering supplies that made operations possible. That railroad fit the bill exactly.

—

Grant’s command at Paducah was ready for action, and it was given a mission to drive up the Tennessee River, which in western Tennessee flows south to north. But for Grant personally there was a catch:

Fort Henry:

You will place Major-General C. F. Smith in command of expedition, and remain yourself at Fort Henry. Why do you not obey my orders to report strength and positions of your command?

H. W. HALLECK,

Major-General.2

It was an indication of Sherman’s newly attained status that on March 10 Halleck gave him an independent mission: He was to take his division southward from Paducah and move up the Tennessee River, and to make a forced march all the way to Corinth to destroy the Memphis and Charleston Railroad.

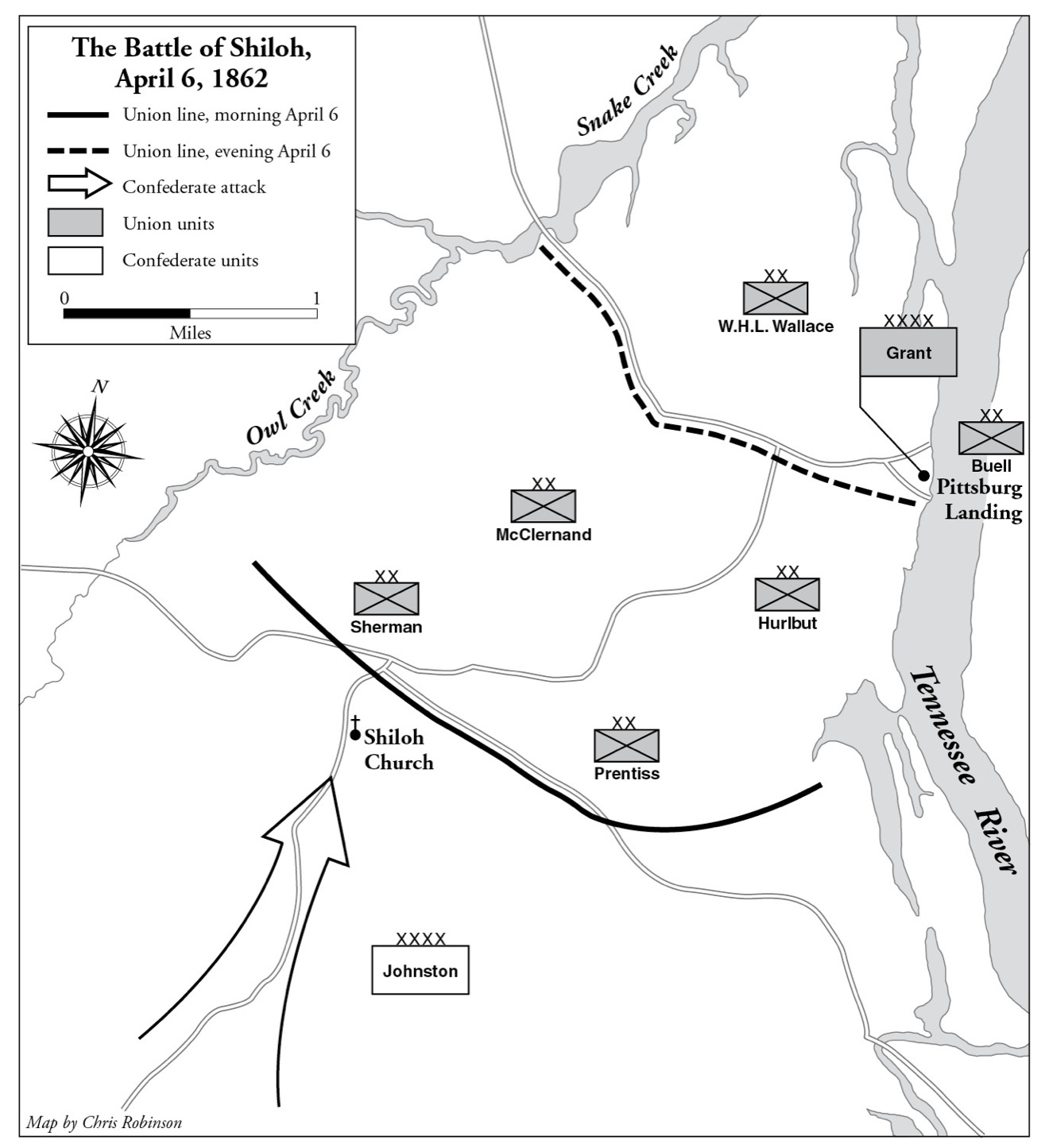

Sherman set out as scheduled, and on the way he observed a spot on the Tennessee River called Pittsburg Landing, where C. F. Smith had already stationed one of his divisions, that of Major General Stephen A. Hurlbut. When Sherman neared his destination, however, he met floods and downpours so severe as to endanger the naval vessels he was dependent on. He therefore withdrew down the Tennessee River to Pittsburg Landing, where he disembarked. He landed his division on the west side of the river at a position on the Corinth road near a church named Shiloh. There he set up camp and prepared for training, something his men still badly needed. He sent messages to a reinstated Grant touting the value of the position.3

Grant honored Sherman’s recommendation and moved his men by water to Pittsburg Landing, arriving on April 3. By the sixth, five of his six divisions, totaling fifty thousand men, were in place or nearby. Four of them, Sherman and three others, were encamped on the west side of the Tennessee River south of Pittsburg Landing. They did not consider it necessary to prepare defensive positions, because all seemed quiet. Grant knew that Buell’s wing of the combined army was closing in after a month’s march from Nashville. Together the two wings would make a powerful force.

Grant appeared to have no feeling of urgency. He did not even take station personally at Pittsburg Landing, preferring more comfortable quarters at Savannah, nine miles up the river. Grant later admitted that he had no knowledge of the whereabouts of Johnston’s Confederate forces—an astonishing admission—and he was not concerned. On the evening of April 5, he sent a message to Halleck, advising, “I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack (general one) being made upon us, but will be prepared should such a thing take place.” He overstated his preparedness, considering that only four of his divisions were on the west bank of the river.4 When the Sixth Division arrived during that same evening, Grant told the commander to camp on the east bank and cross over the next day.5

Sherman was nearly as complacent as Grant. His only nod to the matter of security was to send out a reconnaissance patrol on the evening of April 5, but when it ran into a considerable firefight, he brushed the matter off, assuming that the Confederate troops were a patrol sent out by Confederate refugees from the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas.6

—

In the meantime, things were unsettled among the Confederates at Corinth. Anger and frustration reigned among soldiers and citizens alike, much of the blame laid at the feet of Johnston himself. Some discontents even contemplated removing their onetime hero in favor of someone else. Though they could not quite bring themselves to such a drastic move, they did the next-best thing: They saddled him with a prestigious subordinate, Pierre G. T. Beauregard. It was a bad move; Beauregard made matters worse, because his more cautious views were opposite those of Johnston. He protested against Johnston’s plan to hit Grant at Pittsburg Landing. But Johnston was in command, and he doubtless felt keenly the criticisms that were being directed toward him. He gathered troops from Nashville, Bowling Green, and Corinth and set out to strike. His army of forty-four thousand men left Corinth on April 3, the day that Grant arrived at Pittsburg Landing.

Johnston organized his army into four corps, which he concentrated on the west of the Tennessee River, and made his way to the Corinth road, near which stood Shiloh Church.7 He moved in a column of corps, Major General William J. Hardee leading. Johnston’s plan was to penetrate Grant on the Union left, with his objective Pittsburg Landing itself. If he could thus cut Grant’s four divisions off from their lines of communication, he might be able to destroy Grant’s army as a fighting force. He reached a position two miles from Shiloh Church on the night of April 5, just as Grant was sending his rosy message back to Halleck. Johnston’s men were virtually undetected.

—

At six thirty a.m. on April 6, 1862, Johnston’s men hit Sherman’s and Brigadier General Benjamin Prentiss’s divisions, which were in the most exposed locations. Sherman, at the point farthest from Pittsburg Landing, was hardest hit, and confusion reigned among his volunteer troops. Four thousand of the eight thousand men of his division summarily fled. But as at Bull Run, Sherman was able to rally the rest into some sort of order. He held his position for four hours, until at about ten a.m. he could hold out no longer. His buying that time for Grant to come from Savannah and get matters under control was Sherman’s greatest contribution to winning the battle.

Sherman himself came under heavy fire. One of his aides, standing next to him, was killed outright; in his letter to Ellen, written four days after the battle, Sherman mentions a buckshot wound in the hand and a sore shoulder from a spent ball. He took these scratches in stride, but seemed highly upset in describing the death of a beautiful sorrel mare he had captured recently from the enemy. He had not been able, he added, to “save saddle, holsters, or valise.” Two other horses were shot from under him, and two that were being held in reserve were also killed. So here was a major general “completely unhorsed.”8

Sherman’s slow retreat took his troops to the northwest. The position he finally held at four p.m. was critical to Grant’s defense, in the line of Johnston’s main attack.

—

Unfortunately for the Confederates, their general Albert Sidney Johnston was killed in the early afternoon. His death was unnecessary. In midmorning, he had been hit in the left leg, and the leg was apparently numbed. He considered the wound minor, and sent the nearby medical corpsmen off to tend some wounded soldiers. As a result he bled to death. The South had lost its most prominent general.

When Grant arrived at Pittsburg Landing around nine a.m. on April 6, he set about to restore order. General Lew Wallace’s division, at Crump’s Landing nine miles down the river on the western bank, was ordered forward into the battle. Somehow the orders became mixed up and Wallace wandered around, never participating in that day’s battle. On the positive side, however, Buell’s divisions, camped nearby, began crossing the Tennessee River along with the last of Grant’s own reinforcements.

The critical fight of the battle occurred on Sherman’s left, where Prentiss and W. H. L. Wallace held out in a sunken road called the Hornet’s Nest. Though finally captured, they blocked the Confederate drive to Pittsburg Landing.

Beauregard, now in command of Confederate forces, decided at the end of the day not to press the attack, giving Grant’s army a respite and time to build up and organize. Sherman, coming back to report, found Grant standing casually in the rain under a tree, smoking a cigar. “Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” Sherman asked.

“Yes,” replied Grant. “Lick ’em tomorrow, though.”9

Through the night of April 6 and 7, Grant’s last division and three of Buell’s were ferried across the Tennessee River, past the long lines of men huddled against the near banks seeking shelter from the battle. Buell’s twenty thousand men fell in on the left at Pittsburg Landing, and drove directly south. Despite Grant’s seniority and the fact that the bulk of the troops came from the Army of the Tennessee, Buell insisted that he was commanding his three divisions independently. Grant did not make an issue of Buell’s outrageous claim, though the result was poor coordination and therefore less effectiveness.

This time it was Beauregard who was surprised by a dawn attack. The Confederate troops were not completely reorganized from the fighting of the day before, but they fought in place. Despite the surprise and the fact that Grant now outnumbered him by about two to one, Beauregard managed to bring some order by noontime, and the fighting went on for five more hours. At about dusk, the Confederate commander realized that he had had enough, and he ordered his force to retreat back to Corinth, which they did in remarkably good order. Grant did not pursue, despite Buell’s later claim that he could have continued the attack for another hour of daylight. Sherman’s division, depleted from the fighting the previous day, had fought all day but did not play a major role. By dusk he was back near his position of the morning before. Writing home, he estimated that of his eight-thousand-man division, half had fled, three hundred and eighteen had been killed, and more than twelve hundred had been wounded. Assuming these figures were reasonably accurate, his division now numbered fewer than twenty-five hundred officers and men.10

It had been a grim experience, the bloodiest battle in the nation’s history up to that time, and the first one to convince the public that they were in for a long war.

—

Though Shiloh was by all definitions a Union victory, the “butcher’s bill” of casualties shocked everyone in the North. By no means did the end of the battle and the burying of the dead end the unpleasantness. In fact, Sherman, who was fairly matter-of-fact when describing scenes of nearly unimaginable horror, now rose in wrath, not against the Confederates, but against Buell.* Buell retaliated in kind. He seems to have suffered from considerable ego and a lack of generosity when dealing with his fellow officers. Hardly was the battle over before Buell began making claims that he had come to the “rescue” of Grant. Further, he said, had Grant followed his advice, the victory would have been more decisive. Many of the press believed him, and, more important, Henry Halleck believed him. Therefore, while Sherman’s reputation had been restored by his performance at Shiloh—he had justifiably been hailed as a foremost hero—that of Grant plummeted. The former hero was now considered a failure despite what was really a great victory, and the onetime crazy man was a shining light.

As is usually the case, the elation that followed right after a great victory was superseded by a terrible letdown. Fatigue previously suppressed by the excitement of battle set in, and the horrible sights of the dead and dying took their toll on victors and vanquished alike. Thus, though Sherman received a promotion to major general, he showed no elation when writing to Ellen:

I have worked to keep down, but somehow I am forced into prominence and might as well submit. . . . The scenes on this field would have cured anybody of war. Mangled bodies, dead, dying, in every conceivable shape without heads, legs; and horses.11

The letdown, unfortunately, soon translated into public rage. When visiting reporters witnessed the scenes of the battle’s aftermath, they pounced on the supposed incompetence of the generals in command. Surprise, not the fact of victory, was the theme.12 This was particularly so, ironically, in Ohio, Grant’s native state. On receiving news that Ohio regiments under Sherman had been among the four thousand men who had fled the field, Governor David Tod, who took pride in his nickname of “the soldier’s friend,” immediately concluded that the flaw had been faulty command, not the greenness of the troops. He castigated the “criminal negligence” of the commanders, and, needing a scapegoat, chose Grant. Sherman was largely spared, possibly because of the influence of Tom Ewing and Sherman’s younger brother John. The “accepted wisdom” that Grant had blundered previously at Belmont and had been saved from disaster at Fort Donelson only by General C. F. Smith was again exhumed. Lieutenant Governor Benjamin Stanton came to Shiloh, visited with Sherman among others, and then returned to Ohio, publishing an article in a Bellefontaine newspaper confirming the worst about the incompetence of the high command.

This was too much for Sherman. Though Lieutenant Governor Stanton had not included him in his accusations, Sherman wrote in severe terms for a soldier addressing a politician. “As to the enemy being in their very camps before the officers were aware of their approach,” he started out, “it is the most wicked falsehood that was ever attempted to be thrust upon a people sad and heartsore at the terrible but necessary casualties of war.” Then, somewhat disingenuously, he called it “ridiculous” to talk about a surprise. In finishing up, Sherman pulled out all the stops:

If you have no respect for the honor and reputation of the generals who lead the armies of your country, you should have some regard for the welfare and honor of the country itself. Our whole force, if imbued with your notions, would be driven across the Ohio in less than a month and even you would be disturbed in your quiet study where you now in perfect safety write libels.13

Fighting the trend of public opinion was of no use when the commander in the field was Henry Halleck. Already jealous of Grant’s growing reputation, he once more relieved his aggressive subordinate. He went through with his original plan of assuming personal command, departing St. Louis and joining the army in the field for the drive to Corinth. His subordinate commanders were Buell, John Pope, Thomas, and Brigadier General John McClernand. After a slow advance described derisively by Simon Buckner as a “long siege,” he reached Corinth. Beauregard had evacuated.

Grant meanwhile was temporarily without a command. But he retained the support of a man far more important in the scheme of things than Halleck: Abraham Lincoln. And Grant now recognized Sherman as a foremost general.