The period between Halleck’s capture of Corinth on May 30, 1862, and the surrender of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, was a time of hardship for Union forces. Corinth was occupied shortly after McClellan had essentially admitted failure in his Peninsular Campaign to take Richmond, and that was followed by Second Bull Run (August 1862), Antietam (September), Fredericksburg (December), Chancellorsville (May 1863), and Gettysburg (July 1863). If we consider Antietam as a drawn battle, the only Union success among them was Gettysburg; all the others were Confederate victories. Yet the campaigns in the West, which cost the nation only a small fraction of those in the East, arguably produced greater eventual results. Nearly all the efforts were eventually concentrated on that small town that had only one reason for importance: control of the Mississippi River.

The central figure in the capture of Vicksburg was Ulysses S. Grant, ably assisted by William T. Sherman and Flag Officer David Dixon Porter. So much did Grant dominate the scene that one is tempted to assume that he had been in comfortable control throughout the period. Such an idea is misleading. Grant was always in a struggle to retain whatever position he occupied, and the unswerving loyalty of others, especially Sherman, was what made his efforts a success.

—

After Halleck had relieved Grant as commander of the Army of the Tennessee following Shiloh, he doubtless would have liked to remove him from the scene. However, Grant had too many supporters in high places to be relieved outright. Halleck therefore did the next best thing: He retained Grant as his “deputy commander” of the Army of the Tennessee and left the subordinate units more or less intact. Sherman, for example, remained in command of the Fifth Division for some time before being sent to Memphis, without prejudice, on special duty.

In contrast to the mutual hostility that existed between Halleck and Grant, Sherman retained his warm friendship for “Old Brains,” so a few days before leaving for Memphis, Sherman rode to Halleck’s headquarters for a farewell visit. There, in the course of an otherwise pleasant conversation, Halleck mentioned, almost casually, that Grant had applied for a thirty days’ leave, which Sherman interpreted to mean that his friend was intending to leave the army.

Sherman, in an alarmed state, headed straight for the latter’s headquarters. He soon found it a short distance off the road. What he saw alarmed him further; Grant’s aides were outside the tent, and piled up on the ground was all the office equipment, organized as usual for a move. Sherman asked to see Grant and was immediately ushered in.

“After the usual compliments,” in Sherman’s words, he asked whether it was true that the general was going away. Grant affirmed that he was:

“Sherman,” he said, “you know that I am in the way here. I have stood it as long as I can, and can endure it no longer.” Asked where he was going during his leave, Grant confirmed that he was going to St. Louis. When asked whether he had any special business in that city, he admitted that he had none.

Sherman lost no time in begging Grant to stay. To support his arguments he gave a long description of his own case, how downcast he had been a few months earlier when all the newspapers had declared him crazy. He went on to describe how the recent battle had restored him to “high feather.” If Grant went away, Sherman continued, things would go right along without him. On the other hand, if he stayed, some “happy accident” might restore him to his rightful place. Grant did not appear instantly convinced, but he promised to delay a bit and think the matter over. After Sherman left Corinth—he remembered the date, the sixth of June—he received a note from Grant advising that he had thought the matter over further and had decided to stay.

Sherman sat down and penned a quick note.

Chewalla, June 6, 1862

Major General Grant:

My dear Sir. I have just received your note, and am rejoiced at your conclusion to remain; for you could not be quiet at home for a week when armies were marching, and rest could not relieve your mind of the growing sensation that injustice had been done you.1

Then, for a time at least, the paths of Grant and Sherman parted.

—

Grant’s situation, fortunately, was improved somewhat when Halleck approved his request to move his personal headquarters to Memphis. There he would have a job to do. Memphis had only recently been taken by the Union and the usual confusion reigned. Add to that, most of the people held strong hostility toward their conquerors, and Grant’s administrative chores kept him occupied.

On July 11, Sherman’s prediction regarding Grant’s situation became reality. The authorities in Washington, fed up with McClellan’s failed Peninsular Campaign at Richmond—and overly impressed by Halleck’s capture of Corinth—brought Halleck back to Washington, appointing him general in chief of the U.S. Army. Grant was selected to succeed him at Corinth. Halleck departed on July 17, without uttering a single friendly word.

Sherman was personally unaffected by the animosity between Halleck and Grant. When Halleck left, Sherman wrote him a letter wishing him well:

I cannot express my heartfelt pain at hearing of your orders and intended departure. . . . That success will attend you wherever you go I feel no doubt. . . . I attach more importance to the West than to the East. . . . The man who at the end of the war holds the military control of the Valley of the Mississippi will be the man. You should not be removed. I fear the consequences. . . .

Instead of that calm, steady progress which has dismayed our enemy, I now fear alarms, hesitation, and doubt. You cannot be replaced out here.2

That letter, implying a lack of faith in Grant, is puzzling, and can be explained only by Sherman’s complex nature and his tendency to hyperbole. His opening sentence expressing grief at Halleck’s departure is not surprising given the long friendship the two had shared. Nor is it surprising that Sherman feared that Halleck’s transfer from the Western Theater to the less important Eastern was a bad sign.

Sherman’s expression of fear for the future, however, is astonishing, especially since his friend Grant would be assuming Halleck’s position. Possibly with all his admiration for Grant’s aggressiveness and coolness, Sherman had not yet developed the degree of respect that would grow in the future. In any event, the letter accurately represents Sherman’s views at the time, since he wrote letters to other friends praising Halleck. For the moment, perhaps, Sherman’s passion for order was getting the best of him.

—

Halleck’s departure as commander of the Department of the Mississippi was not done gracefully. On the personal side, he was, as always, less than considerate of Grant. But far more serious than personal discourtesy was Halleck’s destruction of the powerful 120,000-man army he had assembled at Corinth. He had previously sent Buell from Corinth to Nashville with his Army of the Ohio, and now he ordered Grant to send Buell two more divisions. The result was that Grant would be unable to continue offensive action against Beauregard; the best he could do would be to defend what territory Halleck’s once great army had taken.

Why did Halleck disperse his army so? It would be unfair to assume that his sole motive was to prevent Grant’s earning more glories at his expense. It seems more likely that, as a cautious man, he believed that Union forces had captured all the Confederate territory possible, and that they now must simply defend what had been taken. In any event, Halleck had ensured that major offensive action in the Department of Mississippi was, for the time being, at a standstill.

—

Though they were separated, the next few months were not completely lost for the growing comradeship between Grant and Sherman. Grant at Corinth and Sherman at Memphis communicated often and constructively. Each man had much to offer: Sherman had the advantage of broader experiences through his connections with Thomas Ewing and John Sherman, and his experiences in California; Grant somewhat assumed the role of pupil, but he provided stability and common sense to the exchange of views. Only on one all-important matter did they fully agree: The South would never give in until treated in a most brutal manner.3

—

The period of quiet came to an end in early October 1862, at about the time that Grant was officially assuming command from Halleck. Major General John A. McClernand, one of Grant’s corps commanders at Shiloh, visited President Lincoln in Washington and sold him on the idea of raising a new army—to be under McClernand’s command, of course—to advance on the Confederate bastion of Vicksburg, on the Mississippi River. Lincoln heartily agreed to the operation, but to McClernand’s disappointment he assigned the new formation to Grant’s command. Grant and Halleck, for once seeing eye to eye, both considered McClernand, a political general, unfit for the job.4 On Halleck’s urging, therefore, Grant took over the expedition personally. Thus was born the historic campaign of Vicksburg.

Taking Vicksburg did not seem at the time to be a major undertaking. True, its critical importance on the Mississippi was widely recognized,* but the strength with which it was defended was underestimated. That development was tragic in that Halleck, once he had taken Memphis, had neglected to seize the city at a time when it could easily have been taken. Since then Vicksburg had received substantial reinforcements.

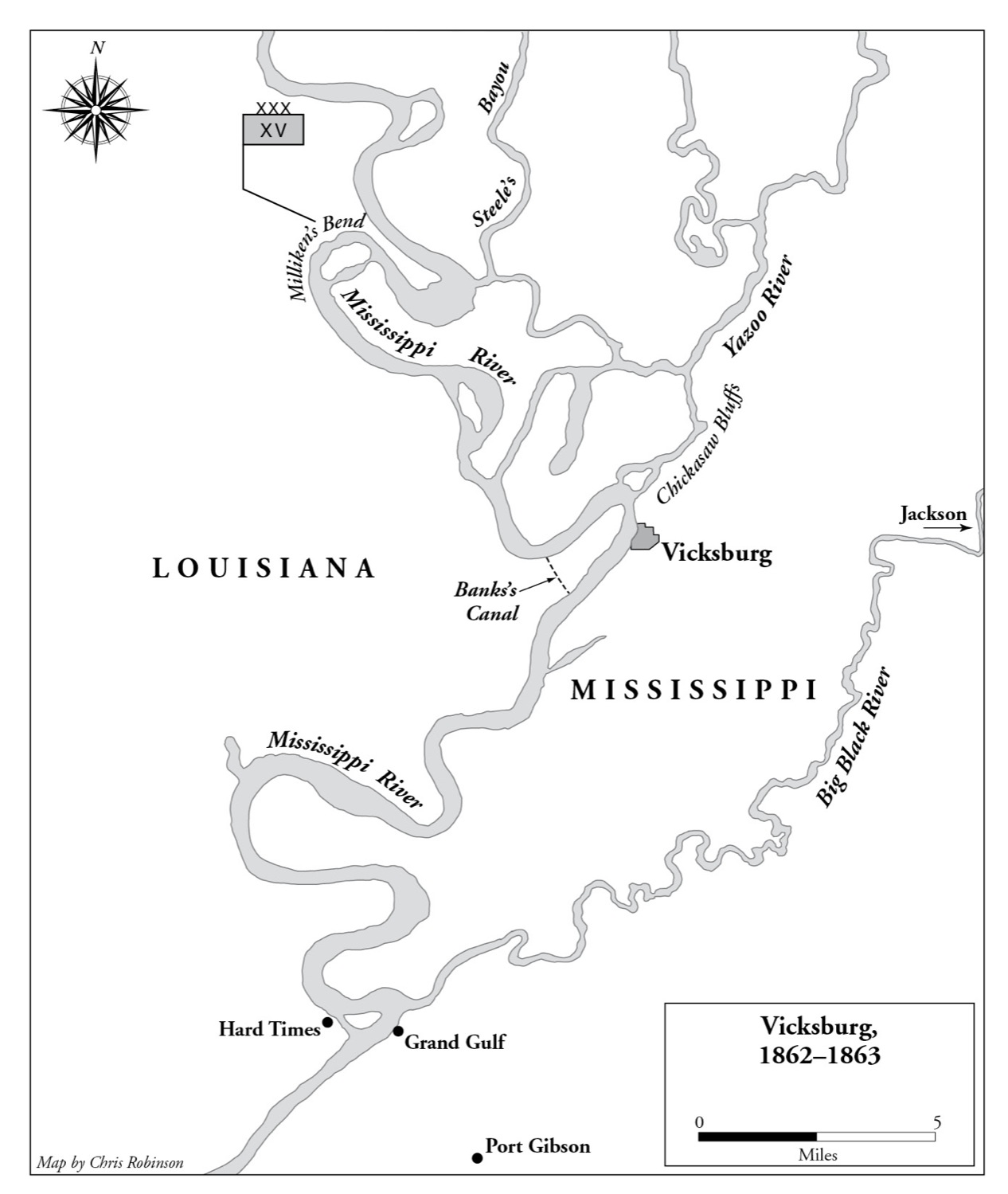

Vicksburg was not the only Confederate bastion remaining on the Mississippi. Far to the south, General Nathaniel Banks was attempting to reduce another strongpoint, Port Hudson. Banks’s force was actually larger than Grant’s, though the position he was attempting to take was less formidable. The relationship between himself and Banks would remain a factor in Grant’s planning throughout most of this campaign.

Months earlier, Banks and Admiral David Farragut had attempted to take Vicksburg even before the city’s garrison had been reinforced. The effort had failed because Farragut’s guns had lacked the punch to subdue those of Vicksburg, and Banks lacked sufficient ground strength to make an assault. Banks had therefore attempted to dig a canal across a strategic point in the river to open north–south traffic, out of the sight of Confederate guns. He succeeded in creating a canal of about fourteen feet wide and fourteen feet deep, but that size was not nearly enough to be useful. Banks and Farragut returned to New Orleans.

But that was a thing of the past. At of the end of 1862, Grant eagerly seized the opportunity for action and began making his plans to take that all-important objective.

—

The position of Vicksburg was often called the Gibraltar of the West. Though situated on the east bank of the Mississippi, it stood at a place where the river makes a double bend, thus giving the town’s defenders clear fields of fire to rake the river. It stood two hundred feet above the water, but the ground to the north was swampy. It would be suicidal to try to attack the bastions from Louisiana, across the Mississippi. An attack straight westward from Corinth presented a precarious supply line to Confederate cavalry. Only from the south was Vicksburg vulnerable, but all of Grant’s forces, including his seven ironclads, were north of the city. Those facts left Grant with little by way of options.

Such obstacles could never, however, stop Grant from making an effort. Still expecting Confederate resistance to be light, he resolved to attack it from two directions, from the east and the north, though either avenue was bad. Deciding to split his forces, he would command one portion of his army, forty thousand men, and send Sherman, whom he now regarded as his second in command, to lead the other, with a strength of about thirty-two thousand.

Such a splitting of forces can be justified only when an enemy is weak, and therein lay Grant’s mistake. It was a good plan for speed, yet only against a weak foe.5

Sherman’s attack was to be made from the north, up the Chickasaw Bluffs. For that he had need for the help of the Mississippi River Squadron, U.S. Navy, commanded by Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, who had been detailed specifically to support him. It was a good combination. Grant’s personality was well fitted for such a relationship, as he had demonstrated at forts Henry and Donelson. Porter, though known as a punctilious, ambitious, and somewhat vain man, was more than anxious to help in any way possible.

Grant and Porter met for the first time at a dinner aboard an army vessel at Corinth in early December. At first Porter was taken aback by Grant’s rumpled informality of dress, but the admiral soon noticed that Grant was an unusual man, with only one thing on his mind: Vicksburg. The general, Porter noticed, was so focused on the pending operation that he neglected to eat the luxurious roast duck that had been served to him. The two men spent only a half hour together, and Grant filled the time explaining his plans. At the end of the short meeting, Porter cheerfully promised the navy’s full-fledged support.6

The meeting with Grant had been called for by protocol, but Porter’s actual role in the operation was to cooperate with Sherman. He therefore went to Sherman’s headquarters in Memphis to meet. When Porter arrived, he was at first impressed by the businesslike atmosphere of the staff, but was offended when he was kept waiting for a whole hour before Sherman appeared. Sherman apologized profusely, insisting that nobody had informed him of the admiral’s arrival. Porter accepted the apology, but then, when Sherman interrupted the conversation to dictate a short message, he nearly left. He soon realized, however, that Sherman could keep several things going in his mind at once. Within a short time Porter and Sherman had “bonded as if they had known each other for years.”7

—

Both efforts to take Vicksburg quickly failed. Porter carried Sherman’s four divisions down the Yazoo River, but on December 26, Sherman’s men were unable to scale the heights at Chickasaw Bluffs. The strength of the Vicksburg garrison resulted from reinforcements available to the fortress because of the failure of Grant’s efforts to take the city by land. After three days of futile repulses, Sherman gave up the effort and returned north to Cairo. Waiting for him there was General McClernand, with orders from Lincoln himself to take over Sherman’s wing of Grant’s army. It was only at that time that Sherman learned of Grant’s failure, which had enabled the Confederates to reinforce Vicksburg.

—

Grant’s wing had never had a chance. Driving a pencil-like thrust through hostile territory made his men too vulnerable to Confederate cavalry leaders Nathan Bedford Forrest and Earl Van Dorn. Grant’s major supply base at Holly Springs was raided and utterly destroyed, and he dropped back to Natchez on December 23.

Both men were operating in the dark. For a while Grant was as unaware of Sherman’s failure as Sherman was of his, so he still held hopes for the overall effort. The campaign, based on faulty intelligence, was ill conceived, so Grant held his favorite subordinate blameless.

Certain elements of the press were not so kind, and eagerly resumed their attacks on Sherman. Sherman counted his casualties as 208 killed, more than a thousand wounded, and 563 missing. As he wrote Ellen, “Well, we have been to Vicksburg and it was too much for us and we have backed out.”8

Sherman did not seem to take his replacement by McClernand with any great grief. Since the order had come from Lincoln himself, through Grant, his relief did not carry with it any disapproval of his performance at Chickasaw Bluffs. Besides being McClernand’s second in command, he was placed in charge of the II Corps, the other being commanded by General George W. Morgan.

Sherman never stopped planning, and he soon came up with a novel idea. He approached McClernand and suggested an attack on Arkansas Post, a Confederate base located forty miles up the Mississippi from Vicksburg. The base, where the Arkansas River flows into the Mississippi, was defended by a garrison of only five thousand bedraggled and vastly undersupplied men, but it was still important because it overlooked the Mississippi. What made the proposal odd is that it constituted a diversion, a sideshow, apart from Grant’s overall plan for taking Vicksburg. This action would contribute nothing to that end.

McClernand was skeptical at first, but he eventually approved. He assembled a force to be carried by Porter’s ships, with Sherman’s corps in the vanguard, to debark at a point about ten miles north of the mouth of the Yazoo. By January 4, 1863, Sherman’s men were ready. Five days later, on the ninth, his force was at Arkansas Post, ready for the attack.

The battle was actually conducted between Porter’s three gunboats and the Confederates at Arkansas Post, more specifically Fort Hindman. For two days, as Sherman watched from the sidelines, Porter’s guns bombarded those of the enemy, causing great destruction. Then, on the top of the embankment surrounding the fort, a white flag appeared. The surrender of the garrison was complete.

Sherman personally carried the news of the success back to McClernand, who had remained aboard his command ship, the Tigress. To Sherman’s disgust, McClernand’s elation was not for the cause it had furthered but for the glory that would accrue to his own name for such a victory.

Grant had been unaware of this action, and when he received word of it, he was angry. He hurried to visit McClernand at his temporary headquarters and after some conversation decided that his subordinate had to go. With the passage of time he eventually conceded the wisdom of the attack; the capture of five thousand men was a tremendous boost. But he learned that both Sherman and Porter viewed McClernand as a liability. They could not, they said, entrust the lives of men to McClernand’s command.

Grant was now in a quandary. McClernand, who had received his major general rank the previous summer, was senior to any other officer in Grant’s command except for Grant himself. Much as Grant would have liked to restore Sherman to his previous post, he could not so long as McClernand was on hand. Therefore, Grant made a major decision: He set McClernand aside and assumed personal command of the Army of the Mississippi himself.

—

With the failure of Grant’s first mad dash to take Vicksburg, he settled down for what he now realized would be a long campaign. This was not to be a single day’s battle such as Bull Run, nor even a two-day struggle like Shiloh. Instead it would constitute a siege, with dangers from other Confederate armies in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana. As historian Charles Bracelen Flood described the situation,

Before making any attack, points near the city would have to be approached through a cleverly defended maze of waterways, many miles of which looped through the marshland of the bayous. Grant saw that it would take an entire campaign, fighting a number of battles, simply to reach the places from which to launch a final offensive, as he put it in a letter to Julia [Grant’s wife], “Heretofore I have had nothing to do but fight the enemy. This time I have to fight obstacles to reach him.”9

Grant’s gloomy predictions turned out to be correct. Historians have listed eleven separate engagements in the campaign, each of which could claim the status of a battle.

—

Grant now organized his Department of the Tennessee into five corps,10 of which Sherman was to command the XV and McClernand the XIII. On January 18, 1863, Grant ordered Sherman’s and McClernand’s corps from Arkansas Post back to Memphis, away from Vicksburg, there to await further instructions.

For a period thereafter, Sherman’s activities were varied. It can be said that Grant’s entire Vicksburg campaign was ad hoc in nature—one experiment after another. So it was with Sherman. He retained command of his XV Corps but he spent the bulk of his time on other duties. One of the roles he played was that of adviser. And Grant seemed to give him missions that were necessary but on the surface did not make sense. Sherman, out of sheer loyalty, accepted the missions even though he knew they would bring on defeat for his corps and bring the press down on his back once more.

Soon after the Arkansas Post episode, Grant gave Sherman a mission that Sherman did not like but performed anyway. It involved not fighting, but digging, an effort to reopen the canal project that Banks and Farragut had abandoned the previous summer. If the canal could be expanded, from six to sixty feet wide, it might be possible to move troops and ships from the Yazoo area to the south of Vicksburg, from which its defenses were most vulnerable. The work could be done, Grant hoped, out of range of the Vicksburg guns.

Grant chose Sherman’s XV Corps and McClernand’s XIII Corps to do the job. Sherman was not enchanted, and he grumbled about the project he called “Banks’s Ditch.” It is not clear how frank he was with Grant himself, but he saw the project as useless. Soon the flooded Mississippi broke through the dam protecting the work on its northern end. The project was abandoned, much to the relief of William Tecumseh Sherman.

—

Meanwhile Sherman was fighting another battle in his lifelong war with the press. He had many such battles, but this one attracted unusual attention. The clash, in fact, was so serious that only President Lincoln’s growing confidence in Grant saved him.

His special enemy this time was a man named Thomas W. Knox, who was the leading reporter for the New York Herald. Knox had surreptitiously and against Sherman’s orders slipped onto one of the troop transports that had unsuccessfully attacked Chickasaw Bluffs. Though few fair-minded viewers blamed Sherman for the failure, Knox published an article in the Herald loaded with accusations made by individual soldiers he had interviewed. He ignored the foul weather and terrain; instead he concentrated on personal attacks against Sherman himself. Knox also accused Sherman of failing to take care of his wounded. His use of the word “unaccountable” seemed to be a resurrection of the term “insane” so widely used a year earlier, when Sherman was commanding in Kentucky.

Predictably, Sherman was furious, both at the article and at Knox’s deliberate violation of his orders banning reporters from the attack. He regarded Knox as a spy—and indeed some material Knox divulged was probably of use to the enemy—and ordered him tried by court-martial. Sherman placed no limitation on the court’s potential verdict; he did not even rule out execution by firing squad as a spy.11

The matter soon became a cause célèbre in the East, but Sherman was not deterred by public opinion. Knox attempted to make amends, and in a personal visit to Sherman he offered to issue at least a partial retraction of his article. Certain mitigating factors, Knox claimed, had been present when the attack had failed. He made an unfortunate statement, however, that the press regarded Sherman as an enemy. That did it. The trial went on.

Sherman participated personally in the trial that followed, garnering testimony from such responsible witnesses as Admiral Porter, who even praised his performance. He sent copies of pertinent documents to Ellen, to his brother John, to Grant, and to his wife’s brother, an accomplished lawyer.

The court-martial dragged on for weeks, and the final verdict was gentler than Sherman had hoped for. It simply banned Knox from Grant’s military department under pain of arrest if he returned. Knox returned to Washington and once there began to fight the verdict, in the process of which he secured an audience with Lincoln himself to plead his case.

Lincoln was in a spot. Much as he supported Grant, he was in an awkward position politically. Just as he bent over backward to placate McClernand, a valuable political ally, he had to avoid offending the Northern press. He promised Knox that he would rescind the verdict of the court-martial if Grant himself approved.

Grant was also in an awkward position. He wrote Knox a reasonable letter praising Sherman in lavish terms and declared that he would refer the request to Sherman. Sherman, however, never gave an inch. In a letter to Knox, he declared, “Come with a sword or musket in your hand, prepared to share with us our fate in sunshine and storm, in prosperity and adversity, in plenty and scarcity, and I will welcome you as a brother and an associate; but come as you do now, expecting me to ally the reputation and honor of my country and my fellow soldiers with you as the representative of the press which you yourself say makes so slight a difference between truth and falsehood, and my answer is Never!”12

Sherman had carried the day. But the Knox case was only one battle in his vendetta with the press. More lay ahead.

—

By early spring, after more than two months of frustration, Grant made one more effort to reduce Vicksburg from the north and avoid the risk of sending Porter’s fleet south beneath the guns of Vicksburg. He still faced one serious problem, however: Porter’s ships could not enter the mouth of the Yazoo because it was dominated by the fortifications that had repulsed Sherman the previous December.

Porter and Sherman therefore decided to try bypassing the mouth of the Yazoo by using a series of bayous, lakes, and streams that had once been courses of the river. The waterway they chose was winding and overgrown with vegetation, but the water was deep. Porter confirmed its navigability by making a personal reconnaissance on March 14.13 The name of the waterway was Steele’s Bayou, and it entered the Mississippi between Vicksburg and the mouth of the Yazoo.

The Steele’s Bayou Expedition was a major effort. Porter’s force consisted of five ironclad gunboats, followed by four towed barges carrying mortars. Behind Porter would be a division of infantry from Sherman’s XV Corps, reinforced by two regiments. Sherman himself would be in command of army troops. Porter’s flotilla entered Steele’s Bayou on March 15, 1863.

At first all seemed to go well. Grant accompanied Porter for the first day, but then, when the flotilla had finished crossing Steele’s Bayou, he departed, leaving Sherman in charge of the troops on the transports. Porter crossed Black Bayou without difficulty, likewise Deer Creek. On Rolling Fork, however, the low branches and underwater vegetation that Porter had been able to plow through previously began to close in. Forward progress was slowed to a half mile an hour, and Confederate sharpshooters began appearing in great numbers on the banks. Eventually an estimated four thousand rebels were on hand, more than Porter could handle.

In bald terms, the expedition had been ambushed. Confederate forces had discovered Porter’s presence even while his ships were still on Steele’s Bayou. Troops from around the area were closing in. To make matters worse, Sherman’s transports, which had originally followed Porter’s ships closely, became cut off. The ironclads could push their way, albeit slowly, but the tall smokestacks of Sherman’s transports could not penetrate the canopy of low branches. A gap grew between the army and navy forces.

Porter now realized his predicament. He attempted to back out, but discovered that the Confederates had blocked his return passage by felling more trees. He sent Sherman an urgent plea for help and issued orders to his ships’ commanders to prepare to demolish the vessels to prevent their falling into enemy hands.

Sherman received Porter’s message on the evening of March 19, more than five days from the beginning of the expedition. He set out first thing the next morning, personally leading two regiments over rough terrain. After a forced march of a day and a half, he arrived at Porter’s position on March 21 with enough strength to disperse the besieging Confederates. By March 27, the Steele’s Bayou force was safely back on the Mississippi.14

The operation had failed, but it had produced two significant results: First, it further strengthened the growing bond between Sherman and Porter, and second, it finally convinced Grant that this last of his experiments to take Vicksburg from the north had to be discontinued. More direct action, despite its risks, was called for.