Sherman did not bother to participate in the surrender ceremonies at Vicksburg. His focus was now on Joseph E. Johnston, whose whereabouts were uncertain. But Sherman suspected that some Confederates were located at Jackson, so on July 4, the day of Pemberton’s surrender, he crossed over to the east bank of the Big Black and essentially retraced his previous steps to Jackson, determined to destroy whatever troops Johnston had there. Unfortunately, from his viewpoint, the small contingent of Confederates had evacuated before he arrived. So Sherman, ever conscious of his long line of communications, withdrew to his position on the Big Black and awaited developments.

—

Port Hudson, at New Orleans, fell soon after Vicksburg, and the Mississippi River was now solidly in Union hands. With no further need for such a powerful force, Grant quickly dispersed his Army of the Mississippi. He personally visited New Orleans but then established his permanent headquarters in Memphis. His various corps were sent to places of strategic importance. For a while, Ord’s XIII Corps (previously McClernand’s) was sent to Natchez, McPherson’s XVII Corps remained at Vicksburg, and Sherman’s XV Corps was ordered to continue occupying his present position along the Big Black. Sherman established his headquarters in a tent near a house belonging to man named Parson Fox. Remembering that a former cadet he had known from Alexandria lived nearby, the general soon found that the young man’s mother was staying at Parson Fox’s farm. When Sherman called on her to pay his respects, the mother bitterly accused the general of killing her husband, the cadet’s father, at Bull Run. Sherman may have not been at war with the Southern people, but they seemed to feel he was at war with them.

The Big Black River, while unfordable, was not wide, so Sherman’s men were within shouting distance of the Confederates across the river. There was little by way of serious fighting. Many of the men, though officially enemies, had once been friends, and they held little or no mutual animosity. One evening a Confederate detachment carrying a flag of truce approached a bridge with a message for General Grant. Sherman accorded the detachment every courtesy. He provided forage for the animals and invited the captain commanding the detachment and his officers and men for a dinner.

It was a memorable evening. The two groups enjoyed their visit, and they seemed to differ on only one subject: the possibility of reuniting the two sections of the country after the bitterness of the Civil War, regardless of the outcome. Sherman contended that reconciliation would be easier than did the captain, who argued that friendly encounters could occur only when the participants were cultured officers such as themselves. But when Sherman took his guest to witness a group of enlisted soldiers enjoying the same conviviality as the officers, he made a point.1

—

On September 22, 1863, Sherman’s period of relative peace came to an end when word arrived that Union general William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland had suffered a staggering defeat at the hands of Braxton Bragg’s Confederate Army of the Tennessee at Chickamauga, a place a few miles south of Chattanooga. Rosecrans had fallen back to Chattanooga and was managing to hold the city. Perhaps he was able to do so only because Bragg did not attack him; he was content to lay siege. Confederate forces held the high ground south of the Tennessee River, cutting off Rosecrans’s supply lines with the intention of starving him out.

Sensing that his presence would be needed at Memphis, Sherman reported to Grant of his own volition the next day. There he learned what Grant knew about the Battle of Chickamauga, fought five days earlier. The defeat had put the authorities in Washington in a frenzy. Within a couple of days Halleck directed Grant to transfer Sherman’s XV Corps from the Big Black to Chattanooga, just incidentally repairing the Memphis & Charleston Railroad as he went along. He also sent two corps from Major General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac—Oliver O. Howard’s XI and Henry W. Slocum’s XII—under the overall command of Joseph Hooker, once commander of the Army of the Potomac. Conveniently, those were probably the three men Halleck would just as soon get out of Washington, but ironically they were destined to play a major part in the coming campaigns in the West.*

—

As he prepared to embark for Chattanooga, a shock hit Sherman that would have affected a lesser man’s performance of duty: the death of his nine-year-old son, Willie. During this period of inactivity, Ellen Sherman had journeyed to visit her husband in Vicksburg, bringing four of their children. Their father took delight in all of them, but he took a special pride in Willie, the boy for whom he held the greatest hopes. As soon as the family had arrived, Willie had adopted the 13th Regular Battalion, Sherman’s bodyguard, and in turn had been adopted by them as an honorary sergeant. Willie was a precocious lad, joining in all the soldiers’ activities, which included drill and riding.

Sherman, along with his troops, was to depart by steamboat for Memphis before moving overland to Chattanooga. The general’s family would continue on to Cairo, Illinois, and head to Ohio. As Ellen was packing for their return home, it was noticed that Willie was missing. Soon located, he showed symptoms of typhoid fever. Despite his illness Ellen was compelled to continue with their plans. In the course of the trip, the doctors quickly gave up hope as the family steamed up the Mississippi. On October 3, 1863, Willie Sherman died in Memphis.

Sherman, burdened with organizing his corps, was overwhelmed with grief. He blamed himself for Willie’s death, holding himself responsible for exposing his son to the unhealthy climate of Vicksburg. He poured out his grief in letters to those who were close to both him and Willie. One letter was directed toward a man to whom he had become especially close, Admiral David Dixon Porter.

It was the 13th Regular Battalion, however, that received Sherman’s greatest expression of grief. In an unusually touching letter to Captain C. C. Smith, the commander, whom he addressed as “my dear friend,” he started with a sentence that summarized it all: “I cannot sleep tonight till I record an expression of the deep feelings of my heart to you, and to the officers and soldiers of the battalion, for their kind behavior to my poor child.”

He went on to review the joy that association with the battalion had given Willie, reminiscing that the boy had actually believed that he was a sergeant in that unit: “Child as he was, he had the enthusiasm, the pure love of truth, honor, and love of country, which should animate all soldiers.”

In closing, Sherman went all out:

Please convey to the battalion my heartfelt thanks, and assure each and all that if in after-years they call on me or mine, and mention that they were of the Thirteenth Regulars when Willie was a sergeant, they will have a key to the affections of my family that will open all it has, that we will share with them our last blanket, our last crust! Your friend,

W. T. Sherman, Major General2

Expressing his sorrow seems to have relieved Sherman’s mind. He sent his family home and went about his duties. Fortunately for him, those duties were pressing, and his mind was soon occupied in his preparations for taking a ten-thousand-man corps across Tennessee from Memphis to Chattanooga. The communications from Chattanooga allowed him to keep in touch with his four divisions, each of which was following a different road or waterway. On October 11 he left Chattanooga himself.

—

Sherman did not expect to encounter any enemy on this trip, so when he left Memphis he took a train whose only security force was his 13th Regular Battalion; the rest of the railroad cars were loaded with clerks, office supplies, and horses for the officers. About nine miles into the journey, the train passed one of Sherman’s divisions—under Brigadier General John M. Corse—that had not yet departed.

At Collierville, only twenty-six miles from Memphis, Sherman noticed that the train was slowing down, finally coming to a stop. Sherman stepped off the train to check the cause and was notified by the colonel of a volunteer regiment that he was being attacked by a large force of Confederate cavalry. Soon a flag of truce appeared and Sherman sent two aides to meet it. The Confederate commander, they reported, had demanded the surrender of the train and a nearby arms depot. Sherman refused, but instructed the aides to engage the enemy in argument and thus buy as much time in conversation as they could.

Sherman then took personal charge of the action. He directed the train’s passengers to take up a defensive position on a nearby knoll, backed the train as much as he could, and awaited the attack. Fortunately the depot itself contained ammunition that he could use to arm his clerks. The enemy attacked, but were beaten back by the veteran 13th Regulars. At one point some of the attackers got to the train and stole some horses, including Sherman’s favorite mare. The enemy also wrought damage to the train engine. After three or four hours of fighting, however, the Confederates withdrew, prompted by the arrival of Corse’s division, to whom Sherman had sent an urgent message.

—

No further such difficulties were met, and at certain points along the way it was possible for Sherman to communicate with his divisions moving eastward. At Corinth, Sherman learned that Grant was heading to Chattanooga to take command of a new department that would include three armies, one of which would be the Army of the Tennessee under Sherman.

Grant had been given free rein in organizing his force. To command the Army of the Cumberland, already on hand, he decided to replace the inept and unlucky Rosecrans with George Thomas, a stolid, conservative man who had earned great accolades as the “Rock of Chickamauga” for his role in saving the Union Army, and had provided the only bright spot in the whole dismal disaster.

Grant’s third army was the Army of the Ohio, commanded by the recently reassigned former commander of the Army of the Potomac, Ambrose E. Burnside. Burnside’s was a small army, consisting of only one corps, the XXIII. Burnside commanded that corps himself, playing a dual role as army and corps commander. It was an odd arrangement, deemed desirable because of the additional administrative powers the title of “army commander” gave him.

Halleck, in Washington, remained frantic, ignoring such niceties as the chain of command. Bypassing Grant, he sent Sherman a message urging him to speed up the rebuilding of the Chattanooga supply line. Sherman took that in stride, and at Iuka, Mississippi, he was pleased to learn that Admiral Porter had voluntarily sent gunboats loaded with supplies as far up the Tennessee River as possible to assist. For his part, Sherman was careful to pick up supplies as he went along so as to avoid taxing the tonnage going into Chattanooga by rail.

—

Sherman reached Chattanooga on November 14, to be greeted warmly by Grant. Sherman’s first reaction was surprise: “Why, General Grant, you are besieged!” Grant merely responded, “Too true.” Together they reconnoitered the front, and Grant explained the situation in detail.

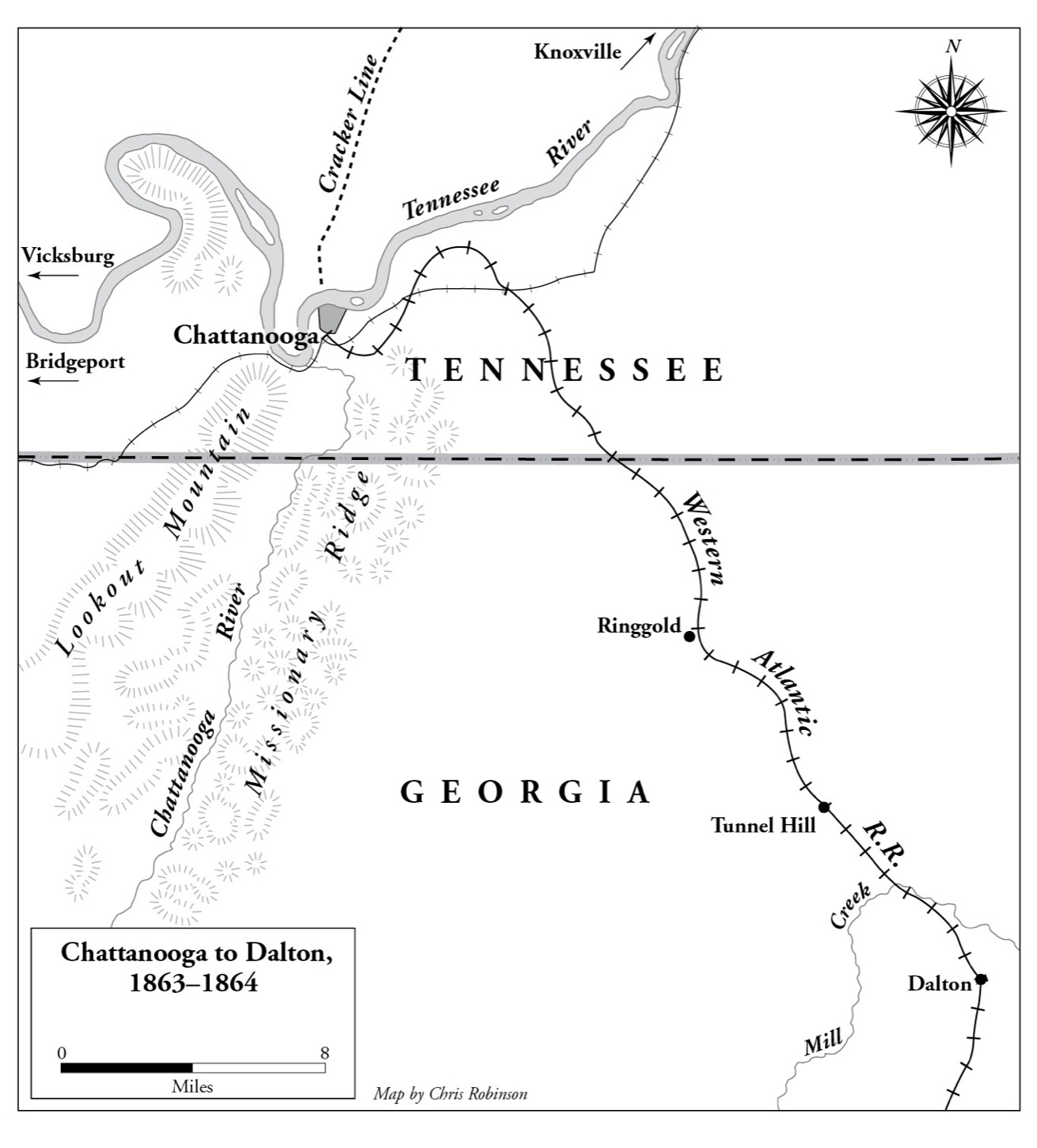

The town of Chattanooga nestled along the south bank of the Tennessee River, a generally meandering stream which at that point straightened out and ran almost exactly east to west. Just to the west of the town the river veered northward. By and large the territory south of the river was occupied by Bragg’s Confederates and the ground to the north by the Union. The one exception was the small town of Bridgeport, Alabama, on the river twenty-six miles by rail west of Chattanooga. Here there was a bridgehead occupied precariously by Grant.*

The Confederate position, on the southern side of the battlefield, was split by Chattanooga Creek, which runs northward before emptying into the Tennessee at Chattanooga. To the west of the creek stands Lookout Mountain, a sudden rise that reaches a height of about twenty-four hundred feet. On the east is Missionary Ridge, a lower (eighteen hundred feet), elongated rise that runs north–south. Both Lookout Mountain and the northern tip of Missionary Ridge dominate Chattanooga. For some reason, Bragg had chosen to deploy most of his strength (Hardee’s and Breckenridge’s corps) along Missionary Ridge, holding Lookout Mountain only lightly.

With reinforcements pouring in, Rosecrans had fortified Chattanooga strongly, and Thomas, after replacing him, had continued to do so. Bragg’s decision to lay siege rather than attack Rosecrans head-on may have made him appear timid, but the siege itself had come within a hair of success. Supplies could not reach all the way to the city on the Tennessee River, so the Union Army in Chattanooga depended on a small road that began at Bridgeport and wound its way through the hills north to a town named Anderson, thence south to his army. So little capacity had this so-called “Cracker Line” that all the army’s horses in Chattanooga had died of starvation, and the men for a time had subsisted on a ration of “four cakes of hard bread and a quarter pound of pork” issued every three days.3

By the time Sherman arrived, Grant had already solved the supply problem. He had made use of the reinforcements Halleck had sent (Hooker, Howard, and Slocum) to enlarge the Union foothold at Bridgeport and to open enough roads on the south side of the Tennessee River to ease the supply situation.

An unwelcome complication had arisen, however. Grant had been placed in charge of all Union forces in the West, and therefore was responsible for the plight of Ambrose Burnside’s IX and XXIII corps in Knoxville. There was little or no military reason for Burnside to be in that exposed position, but President Lincoln had felt an intense desire to protect the people of East Tennessee, almost all of whom had remained loyal to the Union. Burnside’s corps, sent into Tennessee, learned at Knoxville that Confederate general James Longstreet’s corps from Lee’s army had been sent to the area and was threatening him.* Officially, Longstreet was part of Bragg’s Army of the Tennessee, but Bragg commanded him with a loose rein. In addition, Bragg felt secure enough to spare him for the purpose of destroying Burnside. Grant had therefore decided to station Sherman at a point where he could move to reinforce Burnside if necessary.

Grant sent orders to Sherman, at Bridgeport, to cross his XV Corps to the north side of the Tennessee River and take station at the left (east) end of the line, across the river from Tunnel Hill, a knob thought to be at the north end of Missionary Ridge. Then, if Burnside was seriously threatened, Grant could detach Sherman to his aid. The big question was to determine Longstreet’s intentions. Though Bragg had sent him in the direction of Knoxville, Longstreet had as yet taken no positive action. By November 21, Sherman was in position to attack Tunnel Hill on Missionary Ridge or to break off and head for Knoxville.

—

Though Lincoln and Halleck continued to fret over Longstreet’s threat to Burnside, Grant was getting impatient. By November 22 he decided to move against Bragg on Missionary Ridge, using Sherman as his main effort. Since Hooker, in the so-called Battle Above the Clouds, had taken control of Lookout Mountain, Grant planned a double envelopment: Sherman could attack southward on the left tip of Missionary Ridge and Hooker northward from the south end. Thomas, in the middle, was to hit the center of Missionary Ridge, and then turn northward to join Sherman.

Various factors delayed Grant until early in the morning of November 24. Sherman, upon crossing the Tennessee River, found that the hillock he had supposed was part of Missionary Ridge was actually not. He therefore had to reorganize before continuing beyond it. When he reached the main ridge, he found it so heavily defended that he was unable to secure a foothold. Operations ceased for the day.

Despite Sherman’s disappointment, his corps had made an unexpected contribution. In order to defend the north face of Missionary Ridge, Bragg had denuded the center of his line, that facing Thomas. When Thomas had seized his limited objective, therefore, his men, of their own volition, continued on against the remaining Confederates on the ridge. They drove up the slope, and the center of Bragg’s line collapsed. Bragg, who had no stomach for further defense, fled the scene. By the end of the day, the Battle of Chattanooga was history, a clear-cut, inexpensive Union victory.

—

Grant was allowed no time to celebrate; his mind was still on Burnside at Knoxville. But, conscious of what might have been a letdown on Sherman’s part, he wrote a two-purpose order: first, to reassure Sherman, and, second, to share thoughts as to what to do next. Reassuring Sherman was not difficult, because Sherman was no glory hound. So Grant wrote, assuming that Sherman took the same pride in the recent victory as he in “. . . the handsome manner in which Thomas’s troops carried Missionary Ridge this afternoon.” Sherman could “feel a just pride, too, in the part taken by the forces under your command in taking first so much of the same range of hills, and then in attracting the attention of so many of the enemy as to make Thomas’s part certain of success.”

Grant then turned to the matter of relieving Burnside, disclosing that he had been informed on the evening of the twenty-third that the IX Corps in Knoxville had on hand from ten to twelve days’ supplies. Burnside “spoke hopefully of being able to hold out that length of time. . . .”

At that point, Grant did an about-face in the same letter that would have devastated a less competent and devoted man than Sherman. Grant ended the formal letter with one idea:

I take it for granted that Bragg’s entire force has left. If not, of course, the first thing is to dispose of him. If he has gone, the only thing necessary to do to-morrow will be to send out a reconnaissance to ascertain the whereabouts of the enemy.

All well and good. But then, in a postscript, Grant completely reversed himself, now thinking out loud that he should do just the opposite:

P.S. On reflection, I think we will push Bragg with all our strength to-morrow, and try if we cannot cut off a good portion of his rear troops and trains. His men have manifested a strong disposition to desert for some time past, and we will now give them a chance. I will instruct Thomas accordingly. Move the advance force early, on the most easterly road taken by the enemy. U.S.G.4

Grant’s decision to pursue Bragg required Sherman to make a drastic change in the arrangements for his next mission. He had been preparing to move eastward to Knoxville, but he had now been ordered to attack south. That meant a redeployment of troops, artillery, and trains. But by this time XV Corps was expert at adjusting to such last-minute changes, and on November 26 Sherman fell in on the left of Thomas, heading south.

The use of Sherman’s force made the difference in Grant’s decision, very much as Longstreet’s corps made all the difference to Bragg. With Sherman’s XV Corps on hand, Grant held the advantage; with Longstreet on hand, Bragg had the advantage. It had, for example, been Longstreet’s absence at Missionary Ridge that made Grant’s victory there a foregone conclusion. The presence or absence of either decided the outcome.

The pursuit of Bragg was soon dropped. As a result, Grant reinstated his orders for Sherman to relieve Burnside. The difficulties, as usual, were logistical. The distance from Chattanooga to Knoxville is about 130 miles, and though the countryside could provide meat, bread, and forage, it could not provide salt or ammunition. And since it was so late in the autumn, the lack of winter clothing was a cause of suffering. Thus Sherman’s account of the period consists of descriptions of road conditions, blown bridges, and the like. Skirmishes were few and did not impede progress.

Sherman arrived in the vicinity of Knoxville on December 5, only to find that Longstreet, who had never reconciled himself to being detached from Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, had departed for Petersburg to rejoin Lee. That did not mean, however, that Sherman’s grueling march to Knoxville was a waste of time and effort. Had it not been for his approach, Longstreet might not have lifted his threat to Knoxville, and Burnside might have been forced to surrender.

—

The Chattanooga campaign had been a stern ordeal for Sherman and his men. The casualties in the battle and the various skirmishes had not been heavy by the grim mathematics of war, but the endurance required of Sherman and his men had been severe. And its end saw the departure of Sherman from XV Corps.