Grant and Sherman had done their planning well. So precise was it that both armies made their moves into position on the same day, May 4, 1864, Grant in the wilderness of Virginia and Sherman at Chattanooga, Tennessee. That evening Sherman was able to write a letter to Ellen announcing, essentially, that he was now “moving.”

The first phase of Sherman’s campaign involved a series of small towns on the Western & Atlantic Railroad. By the time Sherman wrote Ellen, Thomas had already taken Ringgold, about twelve miles from Chattanooga. Schofield’s army was deployed on Thomas’s left. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee had not yet arrived from Vicksburg, although McPherson himself was personally with Sherman. McPherson did, however, plan to leave the next day to join his command. As to his own plans, Sherman intended to join Thomas the next day at Ringgold. In his letter home Cump conceded, somewhat ruefully, that he expected heavy fighting. But on the whole, he was satisfied. “All my dispositions thus far are good.”1

Progress at first was slower than Sherman had expected—or at least hoped. The next town along the railroad was Tunnel Hill, a noted place named after a nearby hill, through which ran the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio was supposed to take Tunnel Hill as soon as Thomas had Ringgold, but it was May 7 before Schofield was able to capture it. Sherman was familiar with Tunnel Hill from an earlier time in his life, when it had been something of a tourist attraction. On the same day it was seized, he established his small headquarters in a previously selected hotel. He had now gone most of the twenty miles to cover his objective: Dalton, Georgia. Johnston and Sherman dined that evening within five miles of each other.

Dalton, Sherman’s first objective, was the place Braxton Bragg had selected to defend the previous November after fleeing Chattanooga. Since it was a strong defensive position, Grant had decided to let Bragg be until he (later Sherman) could organize a force worthy of ensuring success. In the meantime Johnston, who had replaced Bragg, had been afforded six months to build fortifications. Johnston was a trained engineer, and the result was a position so strong that it could be taken only if the Western Atlantic railroad supplying it from Atlanta could be cut. The terrain to the south was extremely rough, especially for wagons and artillery. Sherman knew that Johnston was determined to hold out at Dalton as long as he could.

How to attack the town—which Sherman determined to do—was a problem. It was protected on the north and west by a stream, Mill Creek, that flowed in north of town from the east, ran about a mile, and then turned abruptly southward, thus shielding the position from both the north and the west. On the west side the position was further strengthened by an escarpment called Rocky Face Ridge that ran north–south about two miles behind Mill Creek. Rocky Face Ridge was exceedingly steep and, as its name implied, rocky. It was broken in only three places. On the north was Mill Creek Gap, where both Mill Creek and the Western & Atlantic Railroad broke through. About two miles to the south was Snake Creek Gap. And two miles farther south was Dug Gap. These breaks in the precipitous walls had been reinforced to Johnston’s best ability.

Sherman was ready to attack the fortifications by May 8, the main effort to be made by Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland. Thomas, allowed to fight his own battle, first chose to hit Dug Gap, the southern one. Besides Thomas’s main effort, McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee, separate for the moment, was to make its way around Johnston’s left flank toward Resaca to cut the railroad. McPherson’s situation, however, was an unknown factor. When he left Sherman knew only that his Army of the Tennessee had encountered delays coming from the west.

—

From the first, things went badly. Thomas’s Union lines charged up the slopes of Rocky Face Ridge on schedule but were soundly repulsed; nothing was gained that day. The next morning Thomas attacked again, this time at Mill Creek Gap farther to the north. Again he encountered failure; the terrain was so formidable that Confederate general Carter Stevenson’s men held the Yankees off even though Stevenson’s forces were outnumbered ten to one.

—

On the ninth, news from McPherson was for a time encouraging. He reported to Sherman that he was within two miles of the Western & Atlantic Railroad at Resaca and had handily dispatched a Confederate cavalry unit, which had fled toward Dalton. Sherman hoped that if McPherson could cut the railroad, he might completely destroy Johnston’s army. He sent orders to both Thomas and Schofield to be ready to pursue on a moment’s notice.

It was not to be. A second message came in from McPherson declaring that the position at Resaca was “too strong,” and that he was preparing a defensive position in the area. Sherman could not help feeling that McPherson had been “too cautious,” and the chance to destroy Johnston had passed. And Johnston would be warned by the Confederate cavalry of his danger.2

The disappointment did not last long. The next evening, when Sherman sat down to dinner at Tunnel Hill, disconsolate over his rebuffs, word came in that McPherson’s turning movement to the south toward Resaca had broken through. He had not yet cut the railroad, but he expected to soon. Sherman sprang from the table and without a moment’s delay sent orders to Thomas to abandon the attacks on Dalton and follow McPherson to Resaca. Only enough men should be left behind at Dalton to make a demonstration against Rocky Face Ridge; his main body was to follow a hidden gulch southward. “I’ve got Joe Johnston dead,” Sherman shouted.

He was only partially right. The alert Johnston noticed how light was Thomas’s presence on Rocky Face Ridge, and a cavalry patrol to the west confirmed that the Union Army was practically gone. With no doubt in his mind, Johnston ordered the Dalton position abandoned and a retreat by the Army of the Tennessee to secure Resaca. The Battle of Dalton thus ended not with a slaughter but with an evacuation.3

—

The Battle of Dalton (or Rocky Face Ridge) was not a big action as Civil War battles went—about six thousand casualties on each side—but it was significant in that it set a pattern for the campaign that followed, from position to position southward along the Western & Atlantic Railroad, which Johnston could not afford to have cut. The campaign, therefore, consisted of a number of actions where Johnston built strong positions, which Sherman flanked from the south, forcing him to evacuate to the next fortified position. The same pattern was repeated at Adairsville on May 17, Cassville on May 18–19, New Hope Church on May 25, Pickett’s Mill on May 27, and Dallas on May 28, over six weeks and a distance of 110 miles.

As the campaign proceeded, a noticeable change began to develop in Sherman’s mind as well as Grant’s. In their exchanges of letters in the planning stage back in April, both men had emphasized that Sherman’s sole objective was to shatter Johnston’s Army of the Tennessee. As things progressed, however, their thinking gradually modified to include the capture of the city of Atlanta, the main center of the Confederate Southeast. The two missions were not incompatible; it was simply a matter of priority.

—

Toward the end of June of 1864, Joe Johnston decided to make a stand. He had wearied of occupying one fortified position after another—not the kind of action that any soldier likes, but inevitable because of Sherman’s relentless drive and overpowering strength. Granted, the Army of the Tennessee was still intact and had inflicted casualties about equal to those it had received. But though Johnston had cause for personal satisfaction, his retreat did not make good reading for the newspaper headlines through the South or for Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

—

Johnston’s reputation in Richmond was not favorable, and a summary of his career might explain why. He was a contemporary of Robert E. Lee, his fellow Virginian and West Point classmate from the class of 1829. Johnston’s experiences, however, had been more checkered and variegated than Lee’s. Lee had spent nearly his whole army life on the civil side of army engineering. Johnston, on the other hand, had started out as an artilleryman, but then, after a few years’ service, had resigned to go into civilian life and had become a highly successful civil engineer. He had fought well during the Second Seminole War and then had decided to rejoin the army. During Winfield Scott’s campaign to take Mexico City in 1847, Johnston had performed heroically as an infantryman at the battles of Contreras, Churubusco, and finally at Chapultepec. He was wounded so often that his “knack” for doing so was noted humorously by Winfield Scott himself.

In the dozen years following the war with Mexico, Johnston had held various positions in the army, and in the summer of 1860, with civil war approaching, he was appointed to the high post of quartermaster general. When the officers of the South resigned their army commissions in order to join the embryo Confederacy, Johnston was the highest-ranking officer to do so.

As a Confederate general, Joe Johnston seemed to be dogged by bad luck, receiving less than his just due for his successes, and unjustified criticism for failures not entirely his fault. Perhaps his courtesy worked to his disadvantage. At the battlefield of the first Bull Run on July 21, 1861, for example, he had declined to replace his junior, Beauregard, who had been the commander on the field before Johnston’s arrival. Thus Beauregard is given credit for the Confederate victory.

Following Bull Run a rift occurred between Johnston and Confederate president Jefferson Davis, who had once been close personal friends. When Davis set out to select five full (four-star) generals, he set an order of precedence that ran Samuel Cooper,4 Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, and P. G. T. Beauregard. Johnston, a sensitive and proud man beneath his courtesy, had expected, because of his top position in the Union Army, to head the list. Davis was unmoved by Johnston’s protests, and Johnston wrote Davis a letter so bitter that Davis read it to his cabinet.5

In spite of their personal hostility, Johnston commanded sufficient respect in the Confederate Army that in early 1862, Davis gave him the important command of the Army of Northern Virginia, the front between Washington and Richmond. With the coming of spring 1862, George B. McClellan, the Union commander in chief, decided that the Confederate forces between Washington and Richmond were too strong to attack directly, and in April he landed an army at Fortress Monroe, at the tip of the Northern Neck of Virginia, in an attempt to seize Richmond by a drive up the peninsula. Johnston moved to Richmond and resisted McClellan skillfully if cautiously. But if Johnston was cautious, McClellan was even more so. It therefore took the Union commander a couple of months to make his way up the peninsula to a spot near Richmond.

On May 31, 1862, Johnston made a stand at Seven Pines (or Fair Oaks), only six miles from Richmond. The results of the battle were indecisive, but most important for Johnston was another wound, so severe that Davis found it necessary to appoint Robert E. Lee in his place. Johnston’s recovery took time, but even when he was eventually fit for duty once more, Davis had no intention of restoring him to his former position. Eventually he was given command of Confederate forces in the West. A reluctant Davis had offered the command to several others first.

—

With such a background, Joe Johnston knew that President Davis would never give him the benefit of the doubt in judging his performance. For that reason, aside from military logic, the retreat that had begun back at Dalton had to stop. To make a stand, Johnston chose a position near Marietta, Georgia, fifteen miles from Atlanta. Kennesaw Mountain and the Chattahoochee River were all that stood between Sherman and the hub of the South.

Kennesaw Mountain was a part of a rough series of ridges running north–south. Near Marietta the railroad made a sharp turn to the east, and the line of hills was astride it. The position was anchored on the north by Kennesaw Mountain itself, the first position actually in a line of three hills. With Kennesaw Mountain on the right of the Confederate line, Pine Mountain was in the middle, and on the left (south) was Lost Mountain. Johnston’s army consisted of William J. Hardee’s, John Bell Hood’s, and Leonidas Polk’s corps. In general, Johnston placed each of his corps on a single hill. And the expert engineer Johnston had joined his positions with a formidable line of trenches across a ten-mile front.

—

Meanwhile, Sherman was undergoing great difficulties. One of his troubles was the abominable weather that plagued him by restricting his maneuver through roads that had become quagmires. Furthermore, he could not afford to look only to his front. His rear was highly vulnerable to the depredations of the Confederate cavalry, especially that of Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest, Sherman feared, was capable of disrupting his supply line through Chattanooga, Nashville, and even Memphis. Sherman did what he could to protect his vulnerable points with much-needed troops. He also took with his command a supply level of twenty days.

—

By June 14, the rains eased, and Sherman took advantage of the letup to make a personal reconnaissance of his front lines. When he reached a place opposite Pine Mountain, he spotted a group of Confederate officers huddled in conference about eight hundred yards away. Despite his own orders to save ammunition, Sherman turned to General O. O. Howard, the commander holding that area, and ordered a nearby three-inch artillery battery to fire three volleys at the Confederates. Howard reluctantly obeyed and Sherman rode on to another position.

What Sherman did not realize at the time was that the group of rebel officers he was taking under fire consisted of generals Johnston, Hardee, and Polk—the Confederate commanding general and two of his three corps commanders. Johnston and Hardee, after the first round hit nearby, quickly took cover, but Polk, slower and perhaps a bit demonstrative, was hit and mortally wounded.

Polk’s death was a big news event throughout the Confederacy. He had been a classmate of Jefferson Davis at West Point, but was known more for his position with the church as a bishop than as a combat leader. His death was observed with a great deal of ceremony. The rumor even began circling that Sherman himself had pulled the lanyard on the artillery piece that had killed the “Fighting Bishop”—which was, of course, nonsense.

Johnston did not include Pine Mountain on his final line of defense. Instead he fell back to a tighter position that included Kennesaw Mountain almost straight to Marietta. Sherman—whose armies had been deployed left to right—Schofield, Thomas, and McPherson decided to make a change and move Schofield over to the right, opposite Johnston’s left flank.

—

Another memorable incident at about this time involved a falling-out between Sherman and Major General Joseph Hooker, commander of XX Corps under Thomas. Hooker had fought well ever since he had brought Howard’s XI Corps and Slocum’s XII Corps to Chattanooga. The group had received accolades, especially in the Battle Above the Clouds—Lookout Mountain. Hooker was, however, a prima donna, and he never forgot that he had once commanded the Army of the Potomac between December of 1862 and June of 1863. Though his name will always be associated with his humiliating defeat at the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May 1863, he had not been put on the shelf. His two-corps force had now been reduced to a single corps, the XX. Despite this, Hooker still seemed to consider himself a bit above his fellow corps commanders.

On June 22, after Thomas had successfully repelled a Confederate attack, Sherman received a message from Hooker, who, as noted, was one of Thomas’s corps commanders.

We have repulsed two heavy attacks, and feel confident, our only apprehension being from our extreme right flank. Three entire corps are in front of us.

At first glance the message might seem innocuous enough, but to Sherman’s eyes it was startling. To begin with, the reference to the right flank was a slap at Schofield, who Sherman understood was firmly entrenched on Hooker’s right. In addition, Hooker’s claim of three corps opposing him ran counter to all of Sherman’s intelligence, which indicated that XX Corps was being faced with only one Confederate corps. And finally, Hooker’s communicating directly with Sherman, bypassing Thomas, smacked of insubordination.

Sherman decided to look into the matter. He went in person to Schofield’s headquarters, where he met with Hooker and Schofield together. On learning of Hooker’s message, Schofield was furious. His troops, he claimed, had been out ahead of Hooker’s. Hooker claimed his innocence of that fact, but to confirm it the three generals rode to the front lines to inspect the scene, where corpses from both commands still lay unburied. On inspection, they concluded that Schofield’s dead were farther forward than were Hooker’s.

The matter having been decided in Schofield’s favor, Sherman and Hooker rode back together for part of the trip to their respective headquarters. It was at that time that Sherman made it clear that this type of incident must not happen again. Hooker did not respond but went into a deep sulk. Nothing more came of the incident for the moment.6

—

The time had come to attack. Because the terrain on his right appeared impassable, Sherman could no longer make use of the flanking movement that had worked so well ever since the Battle of Dalton. On June 23, he telegraphed Halleck in Washington:

We continue to press forward on the principle of an advance against fortified positions. The whole country is one vast fort, and Johnston must have at least fifty miles of connected trenches, with abatis and finished batteries. We gain ground daily, fighting all the time. . . . As fast as we gain one position the enemy has another all ready, but I think he will soon have to let go Kenesaw, which is the key to the whole country. The weather is now better, and the roads are drying up fast. Our losses are light, and, not-withstanding the repeated breaks of the road to our rear, supplies are ample.

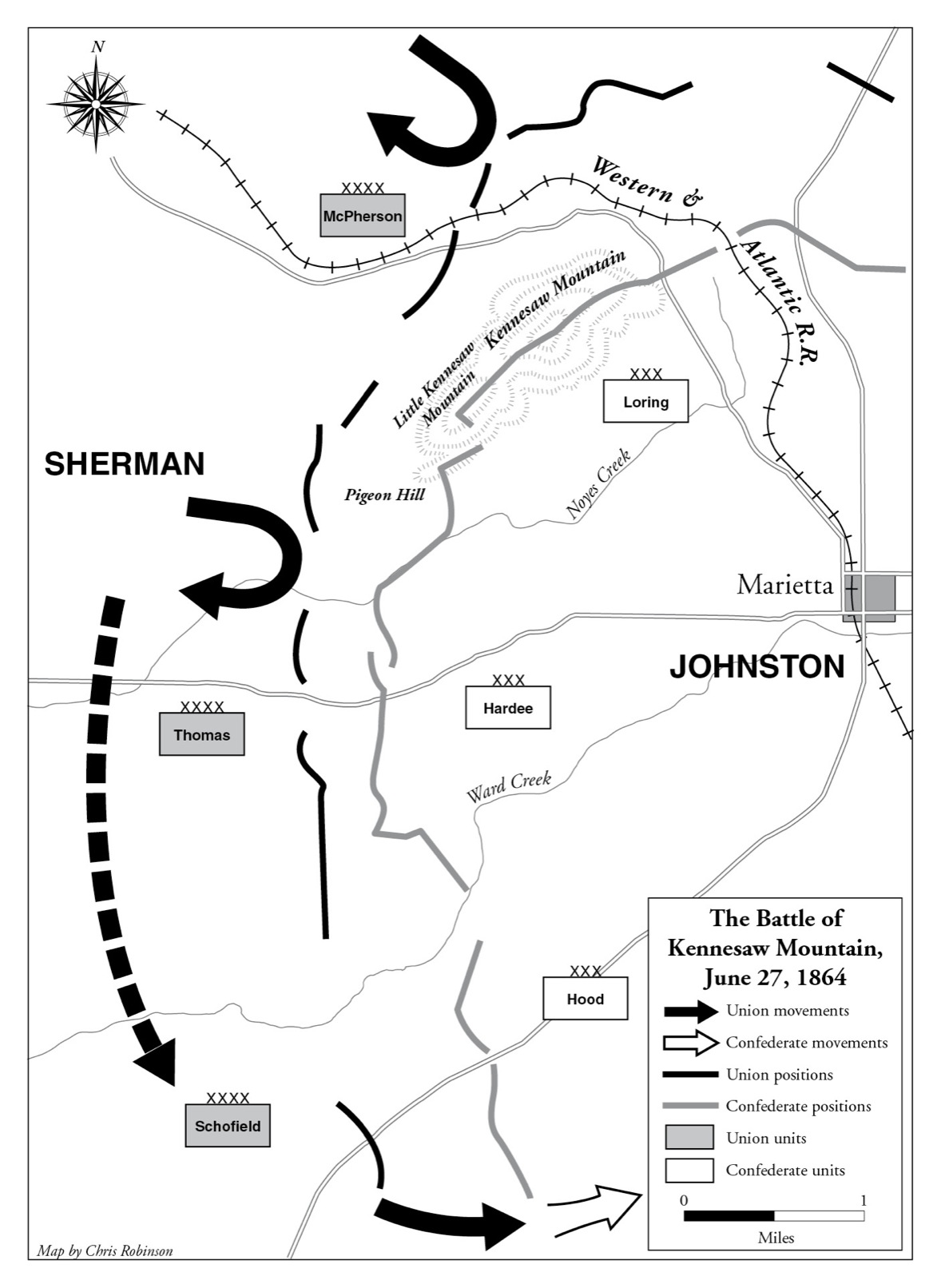

Sherman set the date for the attack on Kennesaw Mountain as the morning of June 27, 1864. He spent the two previous days in intensive preparation. In consultation with his three army commanders, he decided for once to attack Johnston’s fortified lines head-on. He could not extend his lines any farther. Though his force was twice the size of Johnston’s, he already had a front of ten miles and could stretch no more without being too thin to attack in any one place against strong trenches.

Schofield was not to be part of the main attack; he was merely to make a strong demonstration toward Marietta. Thomas, with the strongest army of the three, was to attack in the center. McPherson, on the left, was to attack eastward toward the Chattahoochee River. Sherman and his generals hoped to make one or two penetrations of Johnston’s position, through which he could pour in troops. He did not like this expensive type of operation, but he felt he had no choice.

On the evening of June 26, Sherman was in a pensive mood. Contemplating war in general and his role in it, he wrote Ellen:

Though not conscious of danger at this moment, I know the country swarms with thousands who would shoot me, and thank their God they had slain a monster; and yet I have been more kindly disposed to the people of the South than any general officer of the whole army.7

And four nights later, after the battle, despite great changes in the situation, he seemed to be in the same mood:

It is enough to make the whole world start at the awful amount of death and destruction that now stalks abroad. Daily for the past two months has the work progressed and I see no signs of a remission till one or both and all the armies are destroyed, when I suppose the balance of the people will tear each other up, as Grant says, reenacting the story of the Kilkenny cats. I begin to regard the death and mangling of a couple thousand men as a small affair, a kind of morning dash. . . . 8

—

When the attack was launched at nine a.m. on June 27, Sherman observed it from a knoll in Thomas’s headquarters, using a huge telescope. He could view both McPherson’s and Thomas’s fronts, and what met his eye was not welcome. The skirmishers in both armies made it up to the top of the Confederate parapets, but both fell back with heavy losses, nothing gained. It was, Sherman later noted, the largest attack of the campaign, and it was a resounding defeat.

As at Dalton a month and a half earlier, however, the darkest hour came just before the dawn. As Sherman was counting his losses—five hundred in McPherson’s army and two thousand in Thomas’s9—word came in that Schofield, apart from the main battle, had discovered a route around the south of Johnston’s position toward Marietta. Instantly Sherman changed his plans. He could leave a cavalry screening force in McPherson’s former position and move the Army of the Tennessee around to the right behind the south flank of Thomas. He could then drive to the Chattahoochee Bridge and on to Atlanta.

It was a bold move, and George Thomas, who seemed to revel in presenting opposing views, pointed out that the Western & Atlantic Railroad, which furnished Sherman’s supplies, ran in from the north, whereas the general’s plan called for attacking on the south side of Johnston. Sherman, however, had his mind made up. He loaded ten days’ supplies in his wagons, and by the second of July he was ready.

McPherson pulled out of his lines on the evening of July 2, as planned, in hopes of going around Johnston’s left in the area that Schofield had opened. Or better yet, possibly Johnston would spot the movement and attack, in which case Sherman, as he had advised Halleck, was confident that Thomas could inflict a crushing defeat once Johnston’s army was in the open. Neither hope came to pass, but the movement southward continued.

On the morning of July 3, 1864, Sherman left his tent and went up to an observation post where his special telescope had been set up. Surveying Johnston’s lines, Sherman could make out blue-coated soldiers swarming over unoccupied previously Confederate lines. Joe Johnston had detected McPherson’s movements behind Thomas and had evacuated the position. Kennesaw Mountain was in Sherman’s hands. The Chattahoochee and Atlanta still lay ahead.