Sherman’s return to Goldsboro was uneventful. He took a small boat from City Point to Old Point Comfort, where he picked up his brother John and Edwin L. Stanton Jr., son of Secretary Stanton. They arrived back at Sherman’s headquarters on March 30.

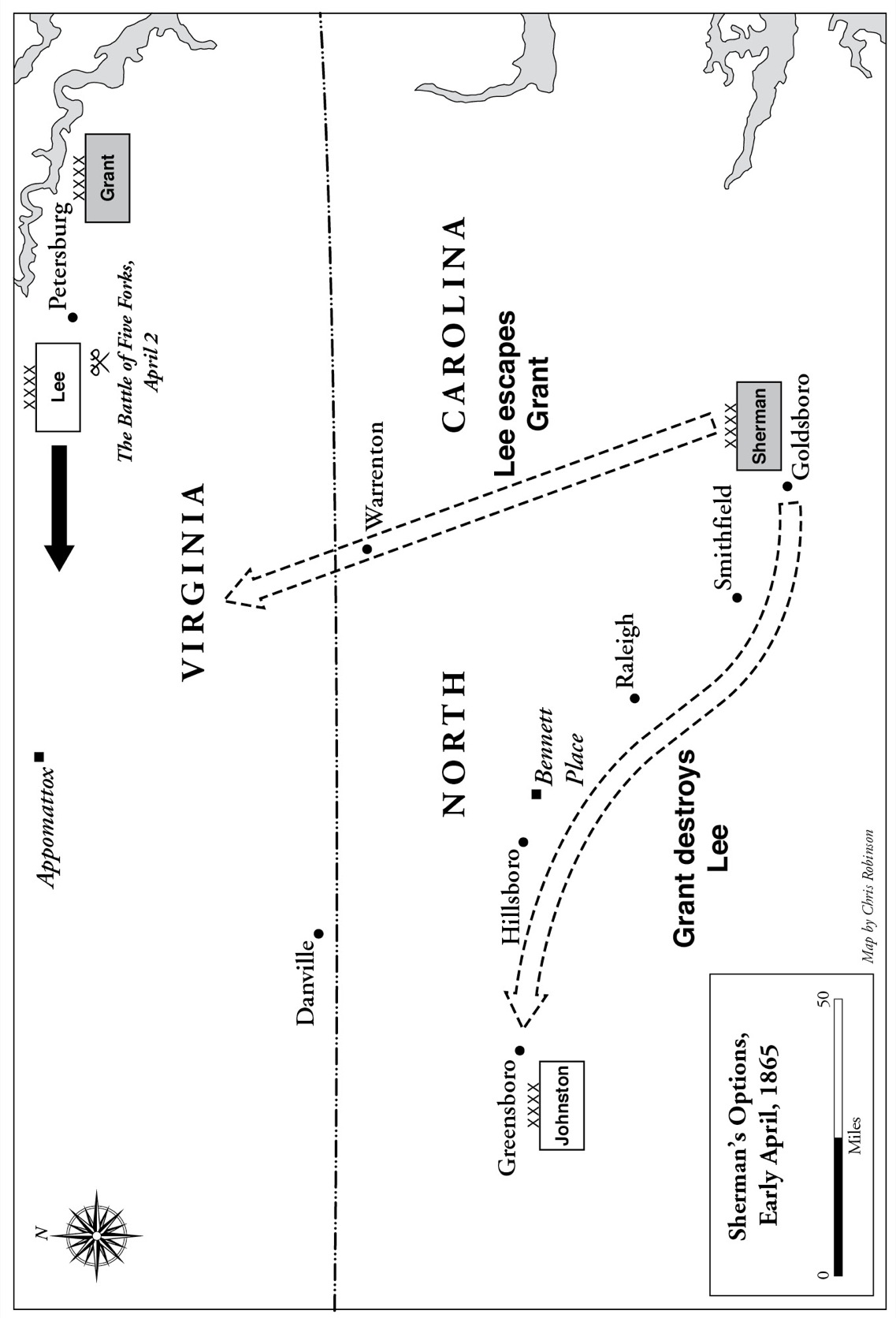

Sherman had every reason to be confident in his situation. His army had now swelled to a strength of nearly ninety thousand troops—eighty thousand infantry, twenty-five hundred artillery, and fifty-five hundred cavalry, well supplied from the North Carolina seaports by numerous railroads over flat terrain. Even if Lee should succeed in evading Grant at Petersburg and joining Johnston, he was certain, he wrote Grant, that his Military Department of the Mississippi could handle the situation easily until Grant, in pursuit of Lee, could catch up. If such were the case, he expected Lee to head westward to Danville and then turn southward to join Johnston, currently at Smithfield, North Carolina. To prevent such a development, Sherman decided to ignore Johnston for the moment and take a position to block Lee’s path. He chose to deploy his army in an east–west position at Warrenton, a small community located almost on the boundary between North Carolina and Virginia.

As usual, Sherman planned to advance to Warrenton with three armies abreast: Slocum’s newly named Army of Georgia on the left, Schofield’s enlarged Army of the Ohio in the center, and Howard’s Army of the Tennessee on the right.1 He attached Kilpatrick’s fifty-five hundred cavalrymen to Howard, as he expected Lee to approach him by way of the right. He set the date for his forward move at April 10, 1865. All of the operations were to be conducted north of the Neuse River.2

—

On April 6, the situation changed dramatically. A message arrived from Grant advising that the Confederate lines at Petersburg had broken on April 2 and that Lee had begun to withdraw westward. All indications were, Grant wrote, that Lee would attempt to reach Danville with what was left of his once-proud Army of Northern Virginia. Major General Philip Sheridan, whose cavalry was following Lee closely, estimated the Confederate force at twenty thousand, “much demoralized.” Grant planned to follow closely, and if Lee made a stand at Danville, he would attack there. He now directed Sherman to turn back to Johnston. “If you can possibly do so,” he wrote, “push on from where you are, and let us see if we cannot finish the job with Lee’s and Johnston’s armies. Rebel armies now are the only strategic points to strike at.”3

—

Based on these orders, Sherman abandoned his plans to drive to Warrenton and headed almost due westward, intending to hit Johnston at Smithfield, where he believed Johnston was still located. He kept the date for departure at April 10.

Sherman arrived at Smithfield on the eleventh, and to his surprise he found the town empty: Johnston had retreated to Raleigh. Continuing in hot pursuit, Sherman received the welcome message from Grant telling of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. An elated Sherman put out the following order:

The general commanding announces to the army that he has official notice from General Grant that General Lee surrendered to him his entire army, on the 9th inst., at Appomattox Court-House, Virginia.

Glory to God and our country, and all honor to our comrades in arms, toward whom we are marching!

A little more labor, a little more toil on our part, the great race is won, and our Government stands regenerated, after four long years of war.

—

The troops were understandably exuberant to learn that the long and bloody war was almost over. Sherman, though likewise elated, was still required to face what problems might arise from this development. He had no concern over the prospect of a battle with Johnston; the latter’s force was pitiable. But if Johnston decided to flee, Sherman had no way to catch him. Both armies were located in Confederate territory, and Sherman feared that whatever remained of the Army of the Tennessee might break up in small pieces and reassemble somewhere else—or resort to guerrilla warfare. The answer, as Sherman saw it, was to exact a quick surrender from Johnston, on terms similar to those Grant had offered Lee.

Fortune seemed to smile on him. Almost immediately after he entered Raleigh, a Confederate locomotive entered town from the west, and Sherman soon learned that a courier was carrying a message addressed to him. It was from Johnston himself:

The results of the recent campaign in Virginia have changed the relative military condition of the belligerents. I am, therefore, induced to address you in this form the inquiry whether, to stop the further effusion of blood and devastation of property, you are willing to make a temporary suspension of active operations, and to communicate to Lieutenant-General Grant, commanding the armies of the United States, the request that he will take like action in regard to other armies, the object being to permit the civil authorities to enter into the needful arrangements to terminate the existing war.

This was exactly what Sherman had been hoping for, and he replied with no hesitation. He was empowered to negotiate, he said, and was willing to do so. To facilitate negotiations he was stopping the forward movement of his army. He further volunteered that his demands would be based on those that Grant laid on Lee.

It took two days for an answer to arrive. But again, when a courier came in on the sixteenth, it was exactly what Sherman wanted: Johnston would meet him, at a place to be determined, the next morning, April 17.

—

Sherman left his headquarters early and at ten a.m. he arrived at the Raleigh/Durham railroad station. The arrangements were crafted very carefully, each side careful to ensure safety for its commanding general but to do so with courtesy. The staffs jointly settled on a farmhouse located between Durham Station and Hillsboro. Its owner, a man named Bennett, readily made it available.

Though Sherman and Johnston were all too aware of each other’s reputation—they had been fighting each other for months—they had never met before in person. Physically, they could hardly have been more different. Sherman was tall, gaunt, and rough-hewn; Johnston was tiny, smooth, and dapper, fourteen years older than Sherman. Their relations with their respective superiors were far different. Sherman was on the warmest terms with both Grant and Lincoln; Johnston, while he enjoyed a mutual respect with his immediate boss, Lee, shared a mutual animosity with President Jefferson Davis that has become legendary. Most important, the two generals took an instant liking to each other.

They also discovered that their views were very much the same. They shared a hatred of war, and looked on any further bloodshed as sheer waste of human life. Johnston readily agreed that his army was no match for Sherman’s, and to Sherman’s relief had no stomach for reverting to guerrilla warfare if peace negotiations failed. However, in addition to the generous terms that Grant had rendered to Lee at Appomattox, Johnston had an additional request. Rather than confine his surrender to his own army, he proposed a day’s delay in hopes that he could attain authority to surrender all the other Confederate armies in the field. Sherman agreed, and the two friendly antagonists returned to their respective headquarters, agreeing to meet again at the Bennett House at noon the next day.

—

All seemed to be going well, and Sherman set out to board his locomotive, as planned, on the morning of April 18. As he was about to leave, however, he received an urgent message from his telegraph operator to hold up a bit. An important message had come in, the man advised, and he strongly recommended that Sherman wait for whatever time it took to decode it. Sherman trusted his operator and complied.

It was well that Sherman waited, because the message was devastating. It was from Secretary of War Stanton, and it bore the crushing news that President Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated while viewing a theatrical production in Washington on the night of the fourteenth. Vice President Andrew Johnson, a little-known Union Democrat from Tennessee, had assumed the reins of office.

Sherman was stunned and aggrieved, but he typically recovered his senses and began to weigh how this news might affect military-civilian relations and the ongoing peace negotiations. First he confirmed that the telegraph operator had given nobody else the message. He then ordered the man in strong terms that the message must be kept absolutely secret from everyone pending his return. He told nobody on his staff, and when he stopped in Raleigh for a short visit with his XV Corps commander, General Blair, he did not mention it.

Oddly, the first person to whom Sherman divulged the news of Lincoln’s death was Joseph Johnston. As Sherman recounted the story, he carefully observed Johnston’s reaction, noting that sweat had broken out on his forehead. Johnston seemed most concerned that such a crime would reflect on Southern society as a whole. But he and Sherman agreed that the tragedy should not affect the surrender negotiations. Johnston asked Sherman’s permission, however, to bring in a third member to the conference, Confederate vice president John Breckenridge, who was in the vicinity. At first Sherman balked, on the basis that Breckenridge, as a politician, had no place in a military surrender. When Johnston informed him that Breckenridge was also serving as a major general in the Confederate Army, however, Sherman reluctantly relented. Even then he personally warned Breckenridge that he had better flee the country, because public feeling in the North was unforgiving toward him, along with Jefferson Davis.

Sherman then wrote out his terms of surrender. As guidance for drafting them, he had a copy of those signed by Grant and Lee at Appomattox. That document placed all the officers and men of Lee’s army on parole and made provision for keeping records of their names. All Confederate arms, artillery, and public property were ordered to be stacked on the spot, where they were to be picked up by Grant’s men. The most generous provision was that it allowed officers to keep their horses and even their sidearms. That was all.

Incredibly, Sherman’s terms bore little resemblance to those signed at Appomattox. Apparently inspired by his visit with Lincoln and a determination that Lincoln’s philosophy be the guide, his provisions hardly made a nod to such military details as administration of paroles, retention of horses and sidearms, and the like. Instead of stacking arms it proposed that Johnston’s men could keep their arms until they arrived back at their homes. Their state governments’ capitals would then turn them over at a later date to the chief of ordnance. The terms then turned to strictly political matters:

3. The recognition, by the Executive of the United States, of the several State governments, on their officers and Legislatures taking the oaths prescribed by the Constitution of the United States, and, where conflicting State governments have resulted from the war, the legitimacy of all shall be submitted to the Supreme Court of the United States.

4. The reestablishment of all the Federal Courts in the several States, with powers as defined by the Constitution of the United States and of the States respectively.

5. The people and inhabitants of all the States to be guaranteed, so far as the Executive can, their political rights and franchises, as well as their rights of person and property, as defined by the Constitution of the United States and of the States respectively.

6. The Executive authority of the Government of the United States not to disturb any of the people by reason of the late war, so long as they live in peace and quiet, abstain from acts of armed hostility, and obey the laws in existence at the place of their residence.

7. In general terms—the war to cease; a general amnesty, so far as the Executive of the United States can command, on condition of the disbandment of the Confederate armies, the distribution of the arms, and the resumption of peaceful pursuits by the officers and men hitherto composing said armies.

Sherman was well aware of how far he had strayed from Grant’s strictly military terms, so he added a strong caveat:

Not being fully empowered by our respective principals to fulfill these terms, we individually and officially pledge ourselves to promptly obtain the necessary authority, and to carry out the above programme.4

—

Sherman knew that these terms went far beyond military matters, but he believed that the tentative nature of the agreement of his recommendations would justify his decisions. He sent a copy to Grant and Stanton and went on to other things. The war was over—or so he thought.