8

Spencer

Even as a young child, my son Spencer was extraordinarily kind, and it was that kindness that prompted me to search for God. I remember having a vague sense that there was a God—that He was out there someplace—but I only went to church every once in a while, when Vera Mae insisted. But three- or four-year-old Spencer, who came home from his Bible classes joyful and eager to share what he was learning, made me want to find out more about this God he was getting to know. Spencer’s ability to love intrigued me more than anything. He wanted us to pray before our meals, and he sang Christian songs like “Jesus Loves the Little Children,” proclaiming God loved all the children—red and yellow, black and white. He also invited me to attend class with him.

My own son’s love for me led me to where I could discover and experience God’s love for me. I learned later that there was another motivation for Spencer’s invitation: his teacher had offered a prize to any child who brought someone to Sunday school. Spencer knew he was going to get that prize, because he knew I would come if he asked me. At that time, he was more excited about the prize than my salvation! Whatever the reason, Spencer was the human instrument God used to lead me to Him.

In Mendenhall as a teenager, Spencer took on a different kind of leadership—being a pioneer in desegregation efforts. He and four of my other children were in the first wave of black students to voluntarily integrate the white school. That experience was so miserable for them, Vera Mae and I didn’t make them stay after those first couple of years. But when mandatory integration came to the state, Spencer enrolled in Mendenhall High. Spencer was a gifted, accomplished athlete who excelled at every sport he tried: football, baseball, basketball, and track. He was versatile and always stayed very fit. He was especially skilled at basketball. During Spencer’s third year at Mendenhall High, the school’s basketball team won the state championship, and he got the game ball for being the most valuable player on the team. The one white boy on the team was the son of our insurance agent. So there was some goodwill there, and that helped our work in the community.

Later, Spencer graduated from Belhaven College in Jackson—likely the first black to graduate from there. Belhaven came to love having Spencer as a student. When he first started, people didn’t persecute him, but they didn’t love him either, mainly because they didn’t know him yet. But they grew to love him, and the school even named an award after him, placing a plaque on the chapel pulpit to honor him. I will always appreciate Belhaven for how they embraced my son.

Although Spencer became a leader in reconciliation, there was a time when he struggled hard with love and forgiveness. It was after I was beaten in the Rankin County Jail in Brandon on February 7, 1970. Vera Mae brought him and the rest of my children to see me in the hospital. I still looked horrible—all swollen and bruised, bandaged up, and filled with tubes. Joanie ran right out of the room in a rage, yelling that she would hate white people for the rest of her life. Spencer’s reaction was much quieter, but he was also angry. Soon it wasn’t just the white highway patrol officers he was mad at. It was me too. He told me I’d become a different person after the beating. He thought I’d lost my fire because I was talking about forgiveness. It seemed like I was a more submissive person now, and he didn’t like that. He had to get to know his daddy all over again—and even though he still loved me, he didn’t like the new version of me as much as he had liked the old version. Later, he would look back on that time, and he said he could see how something supernatural was happening in me. He eventually embraced the idea of loving and forgiving our enemies, but right after the beating, he wasn’t ready to forgive. He was too angry about what those men had done to his father. It wasn’t just the beating. He had also experienced rejection by whites during school integration in Mendenhall—but what happened in Brandon really added to his anger.

Because Spencer was our firstborn, and that has strong significance in African American homes, Vera Mae raised him to take over for me. Dinner was always a special time at our house, and Vera Mae ordered the table just the way she wanted it. Our youngest girl, Elizabeth, would sit between her mother and me. I would sit at one end of the table, and Vera Mae would place herself where she could easily come and go from the kitchen. The other children, except for Spencer, sat around the table in order of age. Spencer sat at the end opposite me. If I was away, he would sit in my place. The other kids recognized how we groomed Spencer to lead, so when Vera Mae and I would talk with them about a decision we had made, they would often ask, “Does Spencer know about this?” A decision wasn’t final until Spencer was in the loop.

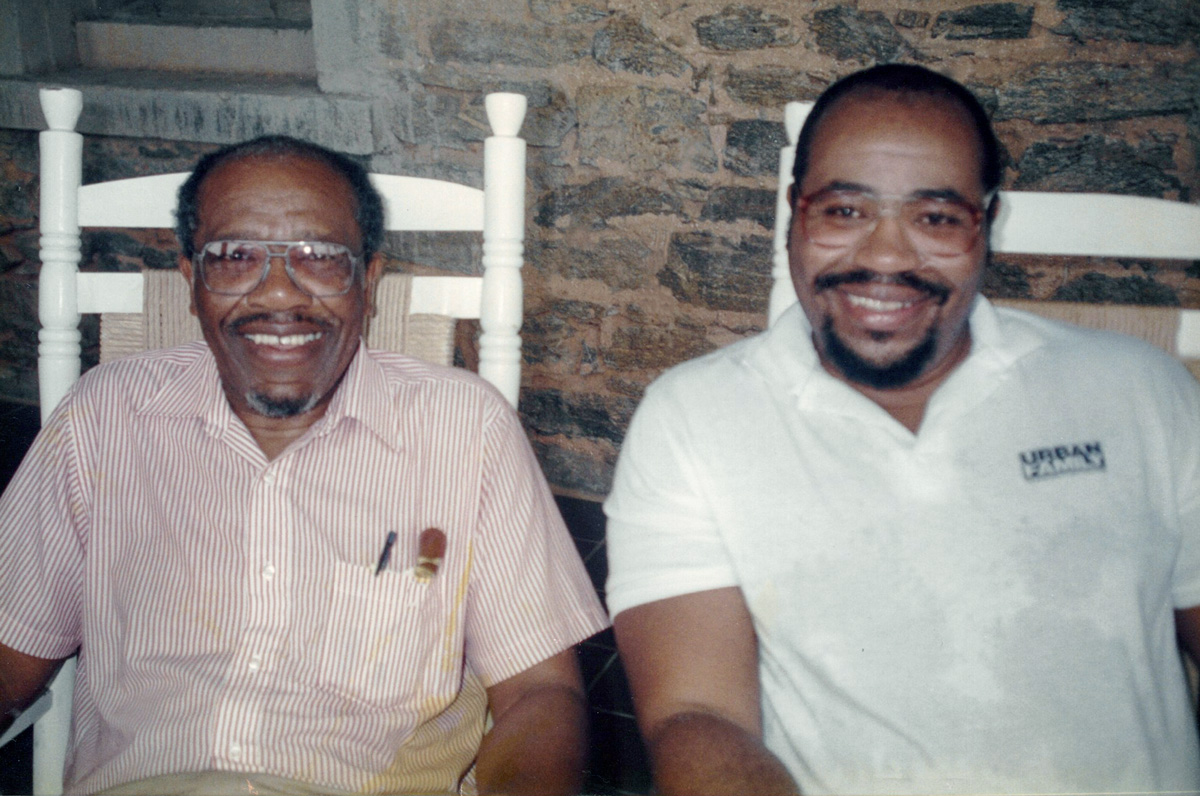

Some children, when they want something, will go to one parent or the other trying to get an easy yes. Not Spencer. He usually came to Vera Mae and me together. He would tell us he wanted to talk with us, and we knew it was significant. Spencer even grew up to look like me. When he got older, into his forties, his hair started to thin, and he shaved his head. If it was good enough for Michael Jordan, it was good enough for him, he said. We took a picture together when he was balding, and we looked like twins.

Our hopes for Spencer extended beyond our family. We wished for him to go into the ministry as well but tried not to push too hard. I wanted to let him find his own way. I think he felt the pressure anyway. He didn’t like having that weight on him, and for a while he really worked to avoid being part of the ministry.

Immediately after college Spencer decided to start his own business. He liked photography, so he thought maybe he could make a living taking portraits of people. That didn’t work out, so he filled in for one of the secretaries at the ministry doing some typing for a while. Working all those hours on the typewriter stirred in him a desire to write. One of his teachers once told us he was the best student she had ever had in English. He didn’t talk a lot during his school days, but he liked words. He did a lot of reading back then too and especially loved historical books.

Spencer still wasn’t ready to jump headlong into the ministry, so he and his brother Phillip started a business where they rebuilt and refurbished car batteries. They would drive down to New Orleans to pick up old batteries for about a dollar, and then they would fix them up and sell them for a decent profit. That worked pretty well until intense competition emerged. The call to writing was getting stronger for Spencer, so he came back to work for Voice of Calvary editing our newsletter, which was called A Quiet Revolution.

By this time Voice of Calvary’s board was starting to see our work as having a national, and even international, scope. It was still grounded in grassroots neighborhood development but was growing into a bigger role and helping to bring this kind of ministry to communities all over the world. So it didn’t really matter where I lived—and Spencer didn’t have to be in a particular place either. So I had the aspiration for him to continue developing his writing and start doing some speaking—but I didn’t have a sense of place attached to that.

When Vera Mae and I moved out to Pasadena, California, in 1982, Spencer continued to work at Voice of Calvary, while my daughters Priscilla and Elizabeth attended boarding school. We did some of the same kinds of community organizing and evangelism work in Pasadena that we had done in Mississippi, but we also started the John and Vera Mae Perkins Foundation for Reconciliation, Justice, and Christian Community Development. In 1992, the foundation launched Urban Family, a magazine geared toward bringing the vision of Christian community development to the black Christian community. Spencer and a white Voice of Calvary staff member named Chris Rice became Urban Family’s editors, and eventually we spun off the magazine as its own ministry. Spencer and Chris, who wrote the book More Than Equals together, eventually changed the name of the magazine to Reconcilers Fellowship and started to do reconciliation workshops on top of putting out the magazine. They had their share of struggles—which I learned about much later—but they were doing important work.

Spencer would have said, though, that his more important ministry was in and through the Antioch community. Antioch had started back in the mid-1980s when a group of folks from Voice of Calvary, including Spencer, Chris, and Joanie, started meeting together for Bible study. They wanted to see what would happen if they took the Bible—and especially the Sermon on the Mount—seriously enough to follow its instructions.

Earlier in his life, Spencer had strayed away from a deep walk with God. He stayed within the framework of what you might call being a “good” Christian, but his faith just wasn’t as strong or as intimate as it had been. By the time this Bible study began, he had married a wonderful Mennonite woman, Nancy Horst, and his faith had been rekindled. He was one of the leaders of the study. After meeting together for a couple of years and wrestling with the Scriptures together, this group decided to pool their resources, buy a big yellow house in the community, and all move in together. They wanted to experience a deeper Christianity than what they generally saw in the society around them. This community was extremely important to Spencer because he loved people so much. For years he had been getting to know and love volunteers and interns as they spent time in Jackson, but then they would leave. He wanted love to last forever. So they developed this intentional community where they were going to stay together for the long haul.

Now, I was never part of that community officially, but I would visit them and could tell they had a really good quality of life together. There were sometimes as many as twenty-nine people living in the community, including several of my grandchildren. I loved how when I’d visit, we’d sit around the dinner table, and we’d start out talking about some event or another—just something that had happened in the community or in the world—and pretty soon we’d be talking about theology. Spencer loved to discuss ideas. So we’d talk about discipleship and reconciliation and all sorts of other topics. They really understood what it meant to be a community, and they had a rich life experience together.

They never could hold on to money though. All of my kids, and especially Spencer, seem to have a sense that if they’re doing the right thing, the money will follow. They get that from Vera Mae, and I agree with it—to a certain extent. The thing is, I also believe it’s important to have good decision-making processes in place to manage the resources God gives you. What happened with Antioch and the magazine was that God would provide—sometimes through Vera Mae and me at the foundation and sometimes through other sources—and the people at the Antioch community would give the money to help others. Their motivation was good. They felt the pain of people’s needs, and they always wanted to meet those needs. Unfortunately, their compassion sometimes made them naive. They would lend money to people who never had any intention of paying them back. Or they would hire someone who wasn’t qualified to do the job, just because they wanted that person to have a paycheck. So money was always a struggle—and I know that burden rested heavily on Spencer.

While we were in Pasadena, I decided that when I turned sixty-five, I wanted to give up my administrative responsibilities and turn my full attention to preaching and teaching. I wanted to move back to Jackson and undergird what Spencer and the rest of the people in the Antioch community were doing. They had a little bit of youth ministry going on and were doing some workshops and internships, but a lot of their energy was directed toward working out their life together as a community. Vera Mae and I wanted to come alongside them and help grow their outward ministry. So we turned the work in Pasadena over to our son Derek, our daughter Priscilla, and Rudy Carrasco. We spent a year in Dallas so I could travel to promote CCDA, and then we moved into the house next door to Antioch. It was wonderful to get up each morning and know we could go over and visit our children and grandchildren. Spencer and Nancy had their three kids—Johnathan, Jubilee, and April Joy. Joanie had married Ron Potter, and they adopted Varah and then Karah. That was a happy time for me.

Spencer was struggling, though, which was hard for me to watch. He and I went out to Colorado Springs at one point to do a father-son radio program with Dr. James Dobson at Focus on the Family. Dr. Dobson and I had been friends for quite a while, and he asked us to come and talk about the black community and the need to see more authentic Christianity among African Americans. So we taped the programs and then took a tour of the Focus on the Family facilities. Spencer saw their success—the efficiency of their systems and how they had plenty of resources to do what they needed to do—and I think that really discouraged him. He felt like, back at Antioch and through Reconcilers Fellowship, they were doing work that was just as important, but they didn’t have the resources they needed.

A couple of weeks later, Spencer injured himself playing basketball and wound up with his leg in a cast. Someone told me later that shortly after his injury, he was trying to do something that required physical strength, but he couldn’t. He just broke down and wept. He must have felt defeated—like he had done everything that was required of him as a Christian, but he and his community still couldn’t quite make things work. I think he felt like they had failed, and that ate at him. Around that same time, he came to visit Vera Mae and me one morning. We sat together for a good hour or more, but he didn’t really say much. When he left, Vera Mae and I wondered what he had wanted. I imagine he was thinking about asking us to give the ministry greater financial support, but he never brought that up.

Right after that, in January 1998, Reconcilers Fellowship held a conference with more than three hundred attendees. Professors, InterVarsity staff members, and other campus ministers from colleges and universities around the United States gathered in Jackson to talk about reconciliation. I missed the first part of it because I was in California for a few days, but I flew back in time to speak at a workshop Saturday morning. On Saturday morning, during a plenary session, Spencer collapsed. The whole conference stopped and everybody prayed over him, and then he was whisked off to the hospital. We found out later it was a blood-sugar-related episode. He was exhausted and physically weak after that, but he came back to the conference so he and Chris Rice could give their keynote address.

People still talk about what he said on that Saturday night. He spoke about grace. He emphasized the need for all minority Christians—especially African American Christians—to forgive white folks, and not just the white folks who prove they “deserve” to be forgiven. He talked about how we minority Christians often play the “race card,” but instead we need to play the “grace card.” It was the first time I had ever heard that saying—grace card—and even though a movie has since come out by that name, I give Spencer credit for coining it.

The sermon he gave that night is included in the revised and expanded edition of More Than Equals. He talked about the church needing to create a culture of grace and how people can hear God’s truth better when it isn’t all mixed up in human judgment. He and Chris shared their own struggles and how they’d had to learn to forgive each other and release each other before they could continue to minister together. It was a hopeful night. It felt like a new beginning for Spencer, Reconcilers Fellowship, and Antioch.

Tragically, Spencer suffered a massive heart attack just three days later at the age of forty-four. He was at home in his study at the time. We lived just a few doors down from him (Antioch had expanded into several houses on the same block), so when I saw the emergency vehicles in front of the house, I ran over and helped get him into the ambulance. I wanted to get in with him, but the paramedics wouldn’t let me. So I drove behind the ambulance to the hospital. When we got there, the ER staff took him into a room and worked on him for about twenty minutes. Then the doctor came out and told me he was gone. He said that Spencer was already gone when he arrived at the hospital, but they thought because he was so young, maybe they could save him. Even after the doctor told me that, he went back into the room and worked on Spencer a little more. Nobody wanted to let him go, I guess.

A little while later the doctor led me into the room where Spencer lay. I remembered somebody once saying something about touching a deceased person while they were still warm—before all the life had gone from them. So I walked around to Spencer’s head and touched his face. It felt like he was a baby again. That was one of the most traumatic experiences I’ve had in my life. The grief I felt in that moment is indescribable. This was my baby—the first person who ever really belonged to me—and he was dead. He was gone.

Then I had to get back in the car, drive home, and tell Vera Mae that our firstborn son was dead. I’ve never done anything as difficult as that. Vera Mae didn’t want to believe me; it sort of seemed like she couldn’t believe me at first. She was supposed to teach a Bible class at four o’clock that evening, and she kept saying, “I’m gonna do my Bible class. I’m gonna do my Bible class.” She said she couldn’t go to the hospital because she had to teach her class. I guess that Bible class was a way to express her dedication to God—or maybe just a way to avoid the reality of what I was saying. Our world was destroyed that day—our hearts were broken, our vision for the future was shattered, and we didn’t know what we were going to do.

My reaction to not knowing what to do was to try to do everything. After I finally convinced Vera Mae to come to the hospital with me, I let our other kids and some friends take her back to the house while I went on to the funeral home. I had made a pre-arrangement for my Uncle Bud’s burial, even though he was still living. I had that transferred to Spencer. I thought I was helping—just doing what had to be done. I found out later that by not consulting Spencer’s wife, Nancy, about these arrangements, I had hurt her deeply—and rightfully so. I didn’t mean to, but I could see, looking back, how my thoughtlessness hurt her.

It was amazing how many of our friends came to Spencer’s wake and funeral. Rich friends, poor friends, friends from down the street and across the country—they were all there with us. At the wake, there was a time for people to share their thoughts. I got up and said to God, out loud in front of everybody, “God, I’m really mad at You. You took my son. I would have liked to have given him back to You, but You took him, and I didn’t have a chance.” I don’t know if I could have voluntarily given up Spencer, but my words came out of my emotion and my feelings of loss and anger. As I spoke them, I thought of two things.

I thought about what missionary Jim Elliot had said about giving up what you can’t keep in order to gain what you can’t lose, and I decided to ask God for something. At the wake, I said, “God, You took my son. Would You give him back to me tonight? Would You give him back so I can give him to You?”

I also thought about this verse of Scripture: “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24 NASB).

At the wake and the funeral, I also said, “God, I would like to give my son back to You tonight as a seed of reconciliation, so that from this seed, many others will grow. I pray that reconciliation will sprout all over this nation, and my son’s death will not have been in vain.” It helped me to do that—to think of Spencer’s death as something that could bring about much good in the world. I didn’t know how exactly that would happen, but I asked God for it and waited to see what He would do.

Losing Spencer was the worst blow Vera Mae and I had ever suffered—the most terrible pain we’d ever felt. But we grieved differently. Before Spencer died, Vera Mae was always energetic—always doing something. She was as much a workaholic as I was. If she wasn’t driving a truck or running the tractor, she was out playing educational games with the kids, teaching them to fish, and being actively involved in all they did. She always kept going. After Spencer died, she hardly got out of bed. When she did get up, sometimes I would find her in the kitchen, just standing at the window and crying. You see, after we moved back to Jackson, Spencer would come see us at our house often. When he’d get to our gate, he’d call out “Momma! Momma!” to let Vera Mae know he was coming.

One time when I found her standing by the sink weeping, she said, “I’ll never hear that voice again.” She was just longing to hear him call out to her one more time. Losing Spencer almost destroyed her.

It also created a great disruption in our relationship—and in my relationship with Nancy. Both Vera Mae and Nancy were overwhelmed and pretty much paralyzed by their grief. Because I wasn’t weeping and mourning the same way they were, they felt like I wasn’t taking Spencer’s death as seriously as they were. But that wasn’t it. I was hurting too, but I had a mission—I was thinking about how I could honor my son’s memory. If I’m honest, I have to admit that even though I had made a commitment to reconciliation after what happened in the Brandon jail, once Spencer and Chris committed to a ministry of reconciliation—and Glenn Kehrein and Raleigh Washington were writing about it too—I kind of let it go onto the back burner. Of course, I was always working on reconciliation through CCDA, but my own personal drive to be a reconciler had lessened somewhat. So once again, Spencer had a big impact on who I would become. After his wake, for a while I wondered, Who is going to do this? Who is going to carry on his ministry of reconciliation? Then I realized that I needed to do it. I needed to make reconciliation a priority in my life again—and at the same time I would be honoring Spencer’s memory.

I started turning over in my mind what I should do. I thought about creating a training center to carry on the teaching ministry, but I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life raising money. So I went back and forth in my mind for a few months, trying to make a decision. Then in mid-1998, a few months after Spencer died, Antioch decided they were going to break up and put up their property for sale. Nancy and the kids were planning to move to Pennsylvania, where her family was, and Joanie and Ron were talking about moving across town. It was like all my dreams for my future just kept crashing down. I continued thinking and praying—and now I was wondering, Should I buy this property and build the center here? I wanted to, but I thought it was going to cost too much money to buy and renovate it.

Then one night I had a dream. I dreamed that people from all over the nation—from the east and the west—had come to Jackson and said, “We want to help you build the center. We want to make it happen.” I dreamed that they were there in the parking lot, with their trucks full of supplies, ready to help, but they couldn’t get in. There was nobody there to open the gate to the fenced-in property.

That dream was so vivid that I jumped up out of bed and went to the window. This was about three o’clock in the morning, and of course nobody was there. But that vision was still so strong and powerful. In my mind I could see those people out there waiting to get in. I’d jumped up so fast that I woke up Vera Mae. When I went back to bed, I said to her, “Honey, let’s buy this property and build a youth center and dedicate it to Spencer’s life.”

She said, “Okay, let’s do it.”

That wasn’t like her at all. The next thing she said sounded a little more like the Vera Mae I knew: “Where are you going to get the money?”

I reminded her about an insurance policy and some CDs we had. They were supposed to be for our retirement and to take care of her if something ever happened to me, but she didn’t even blink when I suggested we cash them in and use the money to buy the property—so that’s what we did.

Pretty soon, our first volunteer group—from Ginghamsburg United Methodist Church in Ohio—arrived. When the volunteers pulled into the parking lot of the property we had purchased, I realized that dream I’d had was unfolding. The Ginghamsburg group brought truckloads of doors and other supplies in their first trip and came back sixteen more times after that. Their work included fixing up an old duplex, which we have since used as our volunteer house, the same place where all those groups that I dreamed about still come and stay today.

Our family, in agreement with others in our ministry, decided to call the new center built by the volunteers the Spencer Perkins Center of Reconciliation and Development. My friend Lowell Noble started doing workshops there. In a way the center saved me from grief. At the same time, it’s how I do my grieving. When I’m out in the yard pulling up grass or inside working on a building or teaching a group of young people about reconciliation and justice, I’m thinking about Spencer. I’m thinking about him, feeling the pain of him not being here, and hoping that his death has made me more committed to Christ and to the ministry of reconciliation.

Sometimes, when people who haven’t lost a child try to comfort me, they say something like, “John, you’re going to get over it. You’ll be okay.”

I know they mean well, but I tell them, “I really don’t want to get over it.” They’re asking me to do something I don’t think I can do—and that I don’t want to do. I want to keep the memories of my child in my life. Of course, I don’t want to be paralyzed by this loss. I want to be able to function. If that’s what they mean by getting over it, then yes, I want that. As time goes by, I want to get to a point where I can talk about Spencer’s death without breaking up. But I never want to forget my child. I don’t even want all of the pain to go away.

That’s why I rush to people now when I hear they’ve lost a child. I remember how it felt to have people trying to talk to me when they didn’t have any idea of the pain. So I want to be there to say to a grieving parent, “I know that pain. I live every day with that pain. You don’t get over it. But you can learn to endure it—you can even learn to do something positive with it.” I can credit these comforting words of wisdom to a dear friend of mine, Pastor John Huffman.

Spencer is buried in a beautiful old cemetery about a mile from my house. It covers about twenty acres of land and is one of the older cemeteries in Jackson. His grave lies in the shade of a tree and is marked with a plaque that says, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant.” I go often to visit his grave and take care of the flowers and just meditate. I know Spencer is in heaven—I don’t think he’s there in the cemetery. But I like to go there and spend time with my memories of him. I have such a deep sense of gratitude for him being the human instrument that brought me to Christ. Sometimes I wonder if that was part of his mission. I have trouble knowing how to express this part, because I don’t want to make it seem like it’s about my importance, but sometimes I think that Spencer’s mission might have been a little bit like John the Baptist’s. Maybe my mission and Spencer’s mission were tied together, and he was the one who went ahead of me, even though I was his father. He was ahead of me in coming to know the Lord, and then he led the way for me in this reconciliation ministry that has been the focus of these last years of my life.

When I think about the role Spencer has played in everything I’ve done that matters, I understand that the length of one’s life is not important; the connection a person makes to the will of God and the mission of the kingdom is important. “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing” became Spencer’s favorite hymn in the last years of his life, and it has become mine as well. Sometimes I sit at Spencer’s grave and think about how I want to be faithful in the mission I’ve taken over from him. Vera Mae and I own the two plots next to Spencer’s. Someday we’ll be buried there beside him. When that day comes, I hope that he, along with my mother, will be able to tell me that I did well with the time I was given—time that went on much longer than theirs did. I hope they’ll be proud of me. As I think of him and my mother waiting for me in heaven, I especially love the line, “Here’s my heart, O take and seal it, Seal it for Thy courts above.” I pray that my heart is sealed to Jesus, to Spencer, and to my mother.

This may sound strange, but I often strain to try to hear Spencer’s voice. The house Vera Mae and I live in now is the house where he died. My favorite room in that house—the room where I like to have meetings, where I go to pray, or sometimes where I just sit—is the room where he used to write. In the black community, our folklore tells us that we’re supposed to be afraid to be where somebody died, because their ghost might be there. But I go into that room and sit there at night with the lights off, wishing that Spencer’s ghost would appear. I wish that he would talk to me. My daughter Priscilla told me that she does the same thing.

I dream about Spencer too. In the dreams, I’ll be spending time with him, having a wonderful time together, but then he always says he has to go. It’s like he can’t stay with me; he has to go back to where he is now. I wake up from those dreams so sad. It’s a little bit like I lose him all over again. But I wouldn’t give up those dreams—those few moments when I can see his face and hear his voice again. Until I get to heaven, that’s the closest I can be to my beloved son.

Frankly, it is the thought of seeing Spencer and my mother again that keeps me motivated today. I don’t expect my mother to be impressed by all my honorary doctorates or the academic centers named after me; rather, I hope she will ask me what I did for mothers like her, mothers dying of nutritional deficiency. And I hope she’ll tell me that she was proud that I started health centers and advocated for the WIC program. I hope the choices I have made and the way I have lived my life prove my love for them. But Paul told us in Romans 8 that nothing, including death, can separate us from the greatest love, the love of God, and so I can rest knowing that Spencer, my mother, and I are always resting together in that love.