The city of Brussels is made up of 19 communes or districts, each with its own council, administration and police force. Every commune has a distinctive character based on its history, major industry and social make-up. The central commune is the only one called Brussels, but most people travelling to the city know the metropolitan conurbation as a whole by this name.

A well-organised, integrated and inexpensive public transport system makes the greater Brussels area easy to explore. Central Brussels is compact and, with comfortable footwear, is a good destination for walking.

This guide divides the city into a number of easy-to-follow sections, taking central Brussels first and then exploring the highlights of the surrounding communes, as well as the battlefield at Waterloo, 15km (9 miles) from the city. We also include excursions to the cities of Antwerp, Bruges and Ghent.

Two languages

In bilingual Brussels, street and building names appear in both French and Dutch. For simplicity, in this book we have used only the French names (French is spoken by 90 percent of the population as a first or second language). For Flanders, where the Dutch language prevails, we have followed the local practice in citing place names.

Parc du Cinquantenaire

Julian Love/Apa Publications

The heart of the city

In the Middle Ages, Brussels was surrounded by a protective wall, with access through seven gates. Inside the wall is an area of 3km by 2km (2 miles by 1.5 miles), a network of narrow cobbled streets, with the Coudenberg hill marking the city’s highest point. When Napoleon Bonaparte took control of Brussels in 1799, he decided to tear down the wall and create wide boulevards around the city. These still exist today as the petite ceinture or inner ring road, a four- to six-lane highway. It is the petite ceinture that, for the most part, creates the boundary between the commune of Brussels and the surrounding communes of the city.

The Grand-Place

There are some places in the world where no matter how wonderful you hear they are, nothing prepares you for seeing them. The Grand-Place 1 [map] is one such place. The beauty is almost overwhelming, the skill of the masons awe-inspiring. Yet the square also has a very human quality, with numerous cafés where you can sit and watch the world go by.

The Maison du Roi fronts one corner of the Grand-Place

iStock

The Grand-Place has long been the heart of the city. Its Dutch name, Grote Markt, indicates that it was developed as the main marketplace. This part of town became Brussels’ commercial heartland at the end of the first millennium, when nearby marshes were drained, creating land for building.

Markets grew up haphazardly, but towards the end of the 13th century, it was clear that a large open area would have to be planned, and houses were demolished to create the space. The foundation stone of the Hôtel de Ville (Town Hall) was laid in 1401 and soon powerful corporations began building their guild houses close to this symbol of secular power.

These buildings were already some 200 years old when the League of Augsburg – an alliance between the United Provinces (Holland), Britain, Spain and Germany – went to war with the French under Louis XIV, the Sun King. In 1695, Louis ordered the bombardment of Brussels. On 13 August, 70,000 men laid siege to the city’s walls, and cannonballs began to rain down, devastating the Grand-Place. Only the spire of the Hôtel de Ville and the facades of three houses remained intact.

In the aftermath of this devastation, the town council decided that a new Grand-Place would be planned and controlled. It approved or vetoed the design of each house fronting the square, resulting in the Grand-Place we see today.

The Hôtel de Ville

The Hôtel de Ville (Town Hall; guided tours in English: Apr–Sept Sun 10am and 2pm, and year-round Wed 3pm) is a magnificent building, whose construction sent an important message about the power that ruled Brussels at the time. While other communities were concentrating their efforts on erecting grand religious buildings, the leaders of Brussels chose to celebrate the civic side of life. The design is an amalgam of covered market and fortified mansion, and each facade was rebuilt to the original plans following the bombardment of 1695. The 96m (312ft) tower, dating from the 1450s, replaced an earlier belfry. A statue of the Archangel Michael, the city’s patron, tops the tower. A series of first-floor galleries and arcades brings coherence to these two separate elements. The Lion Staircase, which now forms the main entrance, was added later (the lion statues in 1770). The coving around the portal features sculptures of eight prophets, while the friezes between the first and second floors depict leading ducal luminaries.

The interior is equally attractive. The highly decorated meeting hall is still home to the council of the commune, while the court room is now used for weddings. One wall of the David and Bathsheba Room is filled with a 1520 tapestry showing Bathsheba at the fountain. Walls in corridors and halls pay tribute in sculpture and paintings to the guildsmen who brought the town prosperity, and the royal families who brought it power. A branch of the Brussels tourist office is on the ground floor.

Flowers & festivals

Between March and October, the Grand-Place is the location of a flower market (Tue–Sun). It is also the venue of many Brussels festivals, such as the annual Burgundian Ommegang parade in July, when the city’s guilds and corporations come together to celebrate their illustrious histories.

Houses of the dukes and guilds

Travelling from the Hôtel de Ville in a clockwise direction around the Grand-Place, the first highlight is No. 7, Le Renard (meaning ‘the fox’, in French), or House of the Haberdashers, built in 1699. The name refers to Marc de Vos (Dutch for fox), one of its architects. It is adorned with statues representing the four continents known at that time, and Justice blindfolded. Le Cornet, next door at No. 6, was the boatmen’s guild house and has a superb Italianate-Flemish frontage designed by Antoine Pastorana. At No. 5, La Louve (1696) is famed for a statue of Romulus and Remus being suckled by a she-wolf (la louve), which gives the house its name. Above this are four statues representing Truth, Falsehood, Peace and Discord. Le Sac at No. 4, the House of Coopers and Cabinetmakers, has one of the facades that remained standing after the French bombardment. Much of it dates from the 1640s, although Pastorana added the upper ornamentation. The house takes its name from the frieze of a man taking something out of a sac (bag), which can be found above the door. No. 3, La Brouette (The Wheelbarrow) was House of the Tallow Merchants, and is now a café (www.taverne-brouette.be). On the corner is Le Roy d’Espagne (King of Spain’s House), which belonged to the guild of bakers. Its classical lines have been attributed to the architect and sculptor Jean Cosyn, and the octagonal dome that tops it – crowned with a gilded weathervane symbolising Fame – adds elegance to the square. Le Roy d’Espagne is now a famous café (www.roydespagne.be).

Aerial view of the Grand-Place

Eric Danheir/Visit Brussels

The northern side of the square, opposite the Hôtel de Ville, is dominated by the large and ornate Maison du Roi (King’s House), built on the site of the Bread Market between 1515 and 1536. The rights to this piece of land passed through the dukes of Burgundy to Emperor Charles V (who was also King of Spain), hence the house’s name. In the 1870s, Mayor Charles Buls wanted to redesign the house. Architect Pierre-Victor Jamaer retained the Gothic style, adding the flamboyant tower and arcades. Although its facade is not to everyone’s taste, you should enjoy the Musée de la Ville de Bruxelles (Museum of the City of Brussels; www.museedelavilledebruxelles.be; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm) inside. Its rooms have exhibits relating to the city’s urban development and political and social history. It also displays original statuary from the Hôtel de Ville. The art collection includes works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens, but the biggest attraction is the display of some 800 ornate costumes worn by that diminutive Brussels mascot, the Manneken-Pis statue (for more information, click here).

Three narrow guild houses sit beside the Maison du Roi. No. 28, La Chambrette de l’Amman (House of the Amman), was the house of the duke’s representative on the Town Council in medieval times. The middle house, Le Pigeon, was home to Victor Hugo in 1851. La Chaloupe d’Or (Golden Longboat, 1697) is easily recognisable; it is topped by a statue of St Boniface. Originally the House of the Tailors, it is also now a restaurant with a lovely interior.

On the eastern side of the square, you will find La Maison des Ducs de Brabant (House of the Dukes of Brabant). This facade of harmonious design is in fact six houses and is named for the figures decorating it rather than its former owners.

Le Cornet, La Louve, Le Sac and La Brouette on the Grand-Place

iStock

Three houses lead back towards the Hôtel de Ville. L’Arbre d’Or (Golden Tree) at No. 10 is the House of the Brewers – look for gilded emblems of hops and wheat – and has a small museum of Belgian brewing, the Musée des Brasseurs Belges (Belgian Brewers’ Museum; www.belgianbrewers.be; daily 10am–5pm). A refreshing beer is included in the admission price. Le Cygne (The Swan), next door at No. 9, is now one of the best restaurants in the city. Originally, it housed the butcher’s guild before becoming a tavern and surrogate home to political theorists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It was here in 1848 that they finalised the Communist Manifesto, though they had both made a promise not to become involved in politics when they were offered asylum in Belgium. L’Etoile (The Star) completes the vista. This house, the smallest on the square, was knocked down when rue Charles Buls was widened and replaced with a second floor supported by arcades. Below the arcades you’ll find a reclining bronze statue of Everard ’t Serclaes, depicted in the throes of death. He was murdered in 1388 for defending Brussels against powerful ducal enemies. This effigy is considered to bring continued good luck to the people of the city. Rub his arm and the nose of his dog to ensure your share of good fortune.

L’Ilot Sacré

The Grand-Place is surrounded by a medieval warren of narrow streets. Their names tell of the activities that took place here in days gone by: Marché-aux-Fromages (Cheese Market), Marché-aux-Herbes (Herb and Grass Market) and Marché-aux Poulets (Chicken Market). This really was the commercial heart of the city. At the beginning of the 19th century, the area was cut by wide boulevards, created when the River Senne was culverted and arcaded (for more information, click here). The name l’Ilot Sacré or the Sacred Isle was conjured up in the 20th century to protect it from redevelopment.

One street south of Grand-Place is rue Violette, home to the Musée du Costume et de la Dentelle (Costume and Lace Museum; www.fashionandlacemuseum.brussels; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm; first Sun of the month free). Two 18th-century brick gabled houses provide the backdrop to a fine collection of Belgian fashions and lace from the 19th century onwards. Further south, at the corner of rue de l’Etuve and rue du Chêne, is Brussels’ famous statue, the Manneken-Pis 2 [map].

The Manneken-Pis

iStock

Manneken-Pis

Why are large crowds always gathered at the corner of rue de l’Etuve and rue du Chêne? There are almost more cameras here than at a Hollywood premiere. This is the site of Manneken-Pis, the irreverent little statue whose method of delivering water to the fountain below embodies the somewhat offbeat attitude of the average native Bruxellois.

The tiny chap is renowned for his wardrobe of around 800 suits – the first one was a gift from the Elector of Bavaria in 1698 – though you may find him naked when you visit. He has been kidnapped three times: once in 1745 by the English, and again in 1747 by the French. On the third and last occasion, in 1817, Manneken-Pis was found broken in pieces. In fact, the statue you see today is a replica of one that was fashioned from the fragments.

North of the Grand-Place you can stroll through the Galeries Royales St-Hubert 3 [map]. Completed in 1847, this beautiful shopping arcade (in fact three separate, but connected arcades) was one of the first of its kind in Europe; nowadays, it features the best in Brussels’ labels. Glass ceilings allow light to flood the walkways. The Galeries intersect rue des Bouchers, a pedestrian-only street peppered with restaurants and one of the most atmospheric places in which to eat on a summer evening.

Taking the western route out of the Grand-Place along rue au Beurre (Butter Street), look out for the Dandoy shop (www.maisondandoy.com) on your left. This family-run business, started in 1829, is a Brussels institution. Stop by for delicious marzipan and speculoos biscuits before you start your itinerary, and, in summer, try the refreshing ice cream. At the end of rue au Beurre, you will find the rear facade of the ornate Bourse 4 [map] (Stock Exchange) directly ahead. A relatively recent Brussels monument, it was completed in 1873 on the site of a former convent.

In a busy part of town, the 11th-century Romanesque Église St-Nicolas (Church of St Nicholas; Mon–Fri 8am–6.30pm, Sat 9am–6pm, Sun 9am–7.30pm; free) is a spiritual oasis. Refurbished in Gothic style in the 14th century and rebuilt several times since, the little church still shows traces of its original rough construction.

Place de la Monnaie to Place de Brouckère

To the north of the Bourse is place de la Monniae, where the Belgian Revolution started in 1830 – crowds rushed out of the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie 5 [map] after hearing the opera La Muette de Portici. Place des Martyrs, just a little way north, commemorates those who died in the fight for independence in 1830. The restored buildings are in the neoclassical style and were constructed in the 1770s, though a number of monuments were added in the 1870s and 1880s. You can reach the square by going along rue Neuve, a busy shopping street.

From place de la Monniae, it is only a short walk to place de Brouckère 6 [map], created in the late 1800s as a homage to the grand squares of Paris. Mayor Jules Anspach wanted his city to rival the French capital and held a competition to make sure the buildings on the square were the finest possible. Today, many have been replaced by more modern structures and those that remain are somewhat lost in a sea of neon. Place de Brouckère is one of the city’s busiest entertainment centres.

The cathedral

The Cathédrale des Sts-Michel-et-Gudule 7 [map] (www.cathedralisbruxellensis.be; Mon–Fri 7.30am–6pm, Sat 7.30am–3.30pm, Sun 2–6pm; cathedral free, charge to crypt, treasury and archaeological zone; crypt by appointment only) is a few minutes’ walk to the northeast of the Grand-Place. The cathedral was founded as a church in 1047, dedicated to the Archangel Michael. Gudule was a saint from Flanders, and her relics were kept in the chapel at St-Géry until being transferred here. The choir dates from the 13th century, and the nave from the 14th century. The church gained cathedral status in 1962.

Sts-Michel-et-Gudule interior

Julian Love/Apa Publications

The approach to the cathedral has been landscaped, and a flight of steps was added in 1860 to make the most of the views of the 15th-century facade. The twin towers are by Jan van Ruysbroeck, the designer of the Town Hall tower. Stained-glass windows show members of the Burgundian and Spanish ruling families, along with biblical scenes. Above the choir are five windows depicting Louis II and his wife Marie of Habsburg, while the windows of the northern transept show Charles V and his wife Isabella of Portugal. A number of royals, including Charles of Lorraine, are buried in the chancel. The pulpit is perhaps the most ornate element in the cathedral. The depiction of Adam and Eve being driven from the Garden of Eden was carved in 1699 by Hendrik Verbruggen of Antwerp. Below ground are the remains of two towers (c.1200), corners of the original church dating from the 10th century.

Comic Strip Center

BCSC/Daniel Fouss

Comic Strip Centre

On the northern outskirts of l’Ilot Sacré, on rue des Sables, is a museum commemorating Belgian artists’ significant contribution to the development of the comic strip as an art form. The Centre Belge de la Bande-Dessinée 8 [map] (Belgian Comic Strip Centre; www.comicscenter.net; daily 10am–6pm) acts as a resource centre for studies into the genre and has exhibits that bring these comic book and celluloid heroes to life, with Tintin and his inventor Hergé taking pride of place. The museum is housed in the Art Nouveau former Waucquez department store, designed and built by Victor Horta in 1906, and faithfully restored.

Hergé

The actual name of Tintin’s creator was Georges Rémi. Hergé is the French pronunciation of his initials rendered in reverse.

The Lower City

West of the Bourse, the Lower City has seen many changes over the last 1,000 years. In the 13th century, a large community of béguines (religious lay women) was established in the Convent of Notre-Dame de la Vigne. The women found safety in the order, living in a large walled compound. The compound was ransacked and abolished during the French Revolution, and now only the Église St-Jean-Baptiste-au-Béguinage remains.

Boulevard Anspach separates the Ilot Sacré from the oldest areas of the city, centred on place St-Géry 9 [map]. The fine covered market hall (1881; Halles Saint-Géry; www.sintgorikshallen.be) in the square is now a cultural centre, surrounded by lively bars and restaurants.

Following the completion of the Willebroeck Canal between Brussels and Antwerp in 1561, goods could be transported to the city by water. Quays built in what is now the Marché-aux-Poissons (Fish Market) have since been filled in, but the street names still relate to their original purposes: quai aux Briques (bricks) and quai au Bois-à-Brûler (firewood), for example. The most central quay reaches as far as place Ste-Catherine with Église Ste-Catherine at its centre. This church originates in the 14th century but was rebuilt in 1854. The square is also the location of the Tour Noire (Black Tower), one of the few remains of the original city wall.

While the commercial town grew on marshy ground, the powerful families lived on Coudenberg (Cold Hill). Today, this part of town still has palaces, and is home to some of the city’s major museums. To reach the museums, walk east from the Grand-Place through the gardens of the Mont des Arts, passing the statues of King Albert I and his wife Queen Elisabeth facing each other across place de l’Albertine. The Monts des Arts complex was a contentious redevelopment. It was a project to create a centre of arts and learning backed by Leopold II but resulted in the destruction of a residential area in the 1890s. Unfortunately, before the rebuilding began, Leopold died, and the project foundered. A large garden area was a temporary solution that lasted until after World War II. The building of the Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique (Belgian Royal Library; www.kbr.be) in 1954 and the public records office (begun in 1960) have encased the remaining gardens in stone and concrete.

Once through the gardens, there is a view up to place Royale ) [map], decorated with a statue of Godefroid de Bouillon, a crusader and ruler of Jerusalem. Behind this you will see the campanile of a grand neoclassical church, the Église St-Jacques-sur-Coudenberg . This part of the capital was changed greatly by Charles of Lorraine when he became governor of the Low Countries in the mid-1700s. He looked towards Vienna for inspiration and brought together the then-disparate architectural styles of Coudenberg to create a unified ensemble. The Musée du XVIIIe Siècle can be seen in elegant place du Musée in the Louis XVI Palais de Charles de Lorraine (Museum of the Eighteenth Century; the palace is closed for renovation until 2019), though Charles died before it was completed.

Place Ste-Catherine

Julian Love/Apa Publications

As you walk towards place Royale you’ll see a splendid Art Nouveau building on your left. This is the Old England Department Store, designed in 1899 by Paul Saintenoy. The building now houses the Musée des Instruments de Musique (Musical Instruments Museum; www.mim.be; Tue–Fri 9.30am–5pm, Sat–Sun 10am–5pm). The museum displays over 1,500 musical instruments in 90 groups relating to type and age. On entering, you receive headphones that allow you to listen to a selection of music at each site.

Musée des Instruments de Musique

MIM/Visit Brussels

Art museums

From place Royale, it is easy to see Charles of Lorraine’s vision for the area. Turning right down rue de la Régence, on your immediate right are the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique ! [map] (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium; www.fine-arts-museum.be; Tue–Fri 10am–5pm; weekends 11am-6pm; first Wed of the month from 1pm; free), including both historical and modern art. This is one of the finest collections in Europe, started at the behest of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Musée d’Art Ancien (Museum of Historical Art) offers more than 1,200 canvasses, with a wealth of Flemish masters on show. Works by Dirk Bouts (1420–75) and Hans Memling (1439–94) showcase the 1400s, with Memling’s La Vierge et l’Enfant being particularly notable. Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450–1516) and Gerard David (c.1460–1523) lead into the 1500s. Pieter Bruegel (1527–69), whose realism had a profound influence on art within the Low Countries, is also represented, along with Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and his pupil Antony van Dyck (1599–1641). Works by Dutch artists Frans Hals (born in Antwerp) and Rembrandt are featured, too. In addition, the museum devotes space to the artistic movements that developed at the end of the 19th century, such as Impressionism – the collection includes paintings by Renoir, Monet and Sisley. On the south side of the museum is a small sculpture garden.

The Musée d’Art Moderne (Modern Art Museum) concentrates on pieces from the late 19th century onwards. Though you enter through a neoclassical building, part of the museum is, in fact, built below ground level with a huge central glass wall allowing light into the galleries. Cubist, Fauvist, Abstract and Surrealist artists are represented. The pieces are arranged chronologically and feature Belgian artists such as Rik Wouters (1882–1916) and Paul Delvaux (1897–1994), along with work by Picasso, Dalí, Miró, Gauguin and Seurat.

In 2009, the Hôtel Altenloh, a mansion from 1779, became home to the Musée Magritte (www.musee-magritte-museum.be; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm; first Wed of the month free from 1pm). The museum showcases a large collection of works by the Belgian surrealist artist René Magritte (1898–1967).

Sandwiched between the Magritte galleries and the Museum of Historical Art is the Musée Fin-de-Siècle (rue de la Régence 3; www.fin-de-siecle-museum.be; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm; first Wed of the month free from 1pm), which displays works from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, including Art Nouveau furniture and decorative pieces.

Parc de Bruxelles and Palais Royal

If you head north from the museum entrance back across place Royale, you will see ahead the trees of the Parc de Bruxelles @ [map]. Originally a hunting preserve of the dukes of Brabant, it has been open land for several centuries. The formal park with ornamental fountains and statuary in the French style was completed in 1835.

When the flag flies over the Palais Royal, the king is in residence

iStock

On its south side, the garden looks on to the impressive front facade of the Palais Royal £ [map] (Royal Palace), once part of the site of the Palace of the Dukes of Brabant. Construction began in 1820 following a fire, which destroyed the previous building. It was greatly modified under Leopold II during his reign (1865–1909), with several of the chambers and the facade given Classical and Louis XVI-style embellishments. The palace is now used for ceremonial occasions, as the royal family lives at Laeken Palace on the northern outskirts of the city. If the king is in residence, you will see the Belgian flag fluttering on the flagpole above the entrance.

The palace is open for tours from the end of July to the beginning of September, but if you want to know more about the Belgian royal family, visit the Musée BELvue (www.belvue.be; Tue–Fri 9.30am–5pm, Sat–Sun 10am–6pm), which is housed in the Bellevue Apartments in the east wing of the palace. The rooms still retain their original splendour. Tasteful exhibits have been added to tell the story of each royal reign in chronological order, including both the personal and professional lives of the monarchs. Artefacts include personal belongings and photographs of the royal family. There is also a memorial to King Baudouin (for more information, click here), who died in 1993.

On the opposite side of the Parc de Bruxelles is the Palais de la Nation, which was constructed in 1783. It has been the seat of the Belgian government since 1830.

Travel back towards the old part of the city via rue Baron Horta and you will find BOZAR/Palais des Beaux-Arts (Centre for Fine Arts; www.bozar.be; exhibitions in the Palace: Tue–Sun 10am–5.30pm, Thu until 8.30pm) on the corner to your left, on rue Ravenstein. Completed in 1928 to a design by Victor Horta, it is greatly admired for its interior detail. Major cultural events such as the Queen Elisabeth Music Contests are held here; temporary exhibitions take place in the foyer, so something is always happening. Also on rue Baron Horta, the Cinematek (www.cinematek.be; daily, times vary), an art-house cinema, has daily screenings.

Congress Column

The Colonne du Congrès (Congress Column), on rue Royale, commemorates Belgium’s Independence Revolution in 1830. Atop its 47m (153ft) shaft stands a statue of King Leopold I (1790–1865). At its base is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

Le Sablon

Once a marshy wasteland, this part of Brussels saw mansions built for the ruling families in the 16th century, but became especially fashionable in the 19th century. Many fine town houses date from this time. Today, it has numerous antiques shops, art galleries, good restaurants and busy bars, which makes it a popular place to browse and have lunch.

It is easy to find the Sablon from the Museé des Beaux-Arts area. A short walk south along rue de la Régence brings you to the Église Notre-Dame du Sablon (Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon; Mon–Fri 9am–5pm, Sat–Sun 10am–6.30pm; free) at the top of place du Grand-Sablon $ [map]. The church was built in 1304 by the guild of crossbowmen, and the statue of Our Lady here is said to have healing properties. The church has undergone several extensions and embellishments, the last in the 19th century. Since the 15th century, the square in the shadow of the church has hosted markets. It is still home to an antiques market every weekend.

Guild statue in place du Petit-Sablon

iStock

Behind the church and across rue de la Régence is place du Petit-Sablon % [map], with its own park, laid out in 1890. It is decorated with historically significant statuary. Each post of the wrought-iron fence around the park is topped with the bronze figure of a man portraying a trade guild. Pride of place within the park is taken by a large sculptured tribute to counts Hornes and Egmont, who were beheaded in the Grand-Place in 1568 following unsuccessful protests against the excesses of Spanish rule. Beyond the square you’ll see the Palais d’Egmont (1534), once the family home of the Dukes of Egmont, but now housing part of the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. You can’t tour the palace, but you can enjoy the gardens.

Les Marolles

Les Marolles is a working-class district that grew on trade and labour skills – coopering and blacksmithing, primarily. The Marolles has never been gentrified (though in recent years this process has been nibbling at its edges) and retains a unique atmosphere, its streets filled with hustle and bustle.

Overlooking the whole area is the Palais de Justice ^ [map], a huge edifice that became a cause célèbre when its plans were revealed. It was one of the largest buildings in Europe when it was completed in 1883, and a large piece of the Marolles had to be demolished to make way for it–much to the consternation of the local people. Everything about the building is on a grand scale, including an entrance porch 42m (150ft) in height.

The rest of the Marolles spreads out to the west and is cut by two main streets. Rue Haute is the longest street in the Brussels commune, and one of the oldest. The artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder lived from 1562 in a house at No. 132 that can be dated from earlier that century. Bruegel and other members of his family are buried in the Église Notre-Dame de la Chapelle & [map] (Mon–Fri 9.30am–4.30pm, Sat 12.30–5pm, Sun 8am–7.30pm; free) at the city end of rue Haute. Consecrated in 1210, the church underwent renovations in 1421 following a fire, and the Baroque belltower was added after the French bombardment of 1695 destroyed an earlier tower. The interior has several fine works, the best being the memorial to Bruegel (the Elder) by his son Jan. At the petite ceinture end of rue Haute, you will find the Porte de Hal, the last remaining medieval city gate, saved from destruction because it served as a prison. Built in the 14th century, it was radically altered in the 19th century in the faux-medieval fashion of the day – most of the top embellishments date from this time. The lower original walls have a much simpler design.

The second major street of the Marolles is rue Blaes, which is famed for its flea market (Mon−Fri 6am–2pm, Sat−Sun until 3pm) at place du Jeu-de-Balle * [map]. You can buy almost anything here, from furniture and clothes to old records. The streets surrounding place du Jeu-de-Balle are dotted with numerous cafés and bars, as well as lots of secondhand stores.

Flea market at place du Jeu-de-Balle

Julian Love/Apa Publications

Beyond the Old City

There are numerous attractions to visit outside the old town and within the other communes of the city. Some can be reached on foot, the rest by public transport.

To the East

The area directly east of the old town has perhaps seen the most change in the last 50 years. This area is the heart of the European Union administration, with numerous office buildings housing EU departments, support staff and the diplomatic missions and pressure groups aiming to influence the EU’s decisions.

The Parlement Européen ( [map] (European Parliament) building is at l’Espace Léopold. (It is often derisively called the Caprice des Dieux by Belgians, because of the building’s resemblance to the box in which the cheese of the same name is packed.) Its curved glass roof rising to 70m (228ft) can be seen from all around this district, and there are particularly pretty views from Parc Léopold at its eastern side. The high-tech Parlamentarium (Willy Brandt Building, rue Wiertz 60; Mon 1–6pm, Tue–Fri 9am–6pm, Sat–Sun 10am–6pm; free) offers visitors the chance to experience the European Parliament in action via a 360-degree digital surround screen. It also features a virtual tour through Europe and the displays on the history of European integration. South of the park you will find the Muséum des Sciences Naturelles , [map] (Natural Sciences Museum; www.sciencesnaturelles.be; Tue–Wed and Fri 9.30am–5pm, Sat–Sun and school holidays 10am–6pm), which aims to enhance understanding of the natural world, and is best known for its dinosaur collection, particularly a group of more than 30 iguanodons found in southern Belgium in 1905. Several have been reconstructed in upright positions, while others are displayed as they were found.

Just a little way further east from the European headquarters is the Parc du Cinquantenaire ⁄ [map]. When Belgium reached its Golden Jubilee, King Leopold II wanted to celebrate by creating a monument to national pride. He enlisted the help of architect Gédéon Bordiau who planned a grand esplanade, formal gardens and a ceremonial arch, with two wings to house museum and gallery space. However, the project hit snags and was not complete for the celebrations. The monumental arch, which features a large bronze quadriga sculpture entitled Brabant Raising the National Flag, was completed in 1888, but the complex later caught fire, and one of the wings has been completely rebuilt in a slightly different style. Today the Cinquantenaire complex houses three museums.

Triumphal arch at Parc du Cinquantenaire

Julian Love/Apa Publications

The south wing is home to the Musée du Cinquantenaire (www.kmkg-mrah.be; Tue–Fri 9.30am–5pm, Sat–Sun 10am–5pm), a collection of art and historical artefacts that ranges from prehistoric times to the present. The Roman and Greek remains are particularly fine, with beautiful mosaics and statuary. Rooms dedicated to earlier Near Eastern civilisation, and ancient Asian and American societies are also impressive. Religious relics, furniture, pottery and jewellery are all of high quality. .

In the south hall next door is Autoworld (www.autoworld.be; Apr–Sept daily 10am–6pm, Oct–Mar daily until 5pm), a collection of over 450 vehicles. Many early Belgian car makers are represented, with a number of pre-1920 Minerva cars and a 1948 Imperia, the last Belgian car produced before production was swallowed by larger European manufacturers. Almost every maker is represented, including Rolls-Royce, Studebaker and Mercedes.

Cafe Belga on place Flagey

Julian Love/Apa Publications

The Musée Royal de l’Armée et d’Histoire Militaire (Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History; www.klm-mra.be; Tue–Sun 9am–5pm) is in the north wing and hall. One of the largest museums of its kind in the world, it covers 10 centuries of military history. In the 19th-century section are uniforms, arms and the personal effects of soldiers from Belgian units, including those of Leopold I. The walls are filled with images of uniformed gentlemen and shot-torn battle flags hang from the ceiling. Another section features 14th- and 15th-century artefacts, with suits of armour, swords and shields. There are displays of tanks and other vehicles, and an aircraft section including a Spitfire and Hurricane from World War II.

To the South

Avenue Louise ¤ [map], leading southeast from the petite ceinture, has cafés, restaurants, department stores and haute couture boutiques. There are several Art Nouveau homes on the adjacent residential streets, including the Musée Horta (Horta Museum; www.hortamuseum.be; Tue–Sun 2–5.30pm) on rue Américaine. The building was designed by Victor Horta as a home and studio. It is considered to be the epitome of Art Nouveau architecture in Brussels.

Art Nouveau

For all the demolition of architectural gems in recent decades, the tide seems to be turning towards preserving what remains of a remarkable heritage. And despite being the capital of so many other things, Brussels is perhaps proudest of being the ‘capital of Art Nouveau’, having been bequeathed some of the finest architecture of this exuberant turn-of-the-20th-century style. Property ‘developers’ and local government connivance have conspired to destroy some buildings, but others remain to dazzle the eye.

The foremost proponent of Art Nouveau, a style typified by naturalistic forms and motifs, was the Brussels architect Victor Horta, some of whose students continued the tradition. Notable examples of the genre are the Solvay Mansion, the cafés De Ultieme Hallucinatie and Le Falstaff (www.lefalstaff.be), Magasins Waucquez department store (which houses the Belgian Comic Strip Centre, for more information, click here), the Old England department store (which houses the Museum of Musical Instruments, for more information, click here), the Tassel House at rue Paul-Emile Jansonstraat 6 and townhouses in square Ambiorix and square Marie-Louise.

Travelling to the end of avenue Louise (by tram from the Palais de Justice) leads you to the Bois de la Cambre, a park with lakes and pleasant paths for walking. Just before the park is the former Cistercian Abbaye de la Cambre (La Cambre Abbey), surrounded by an ornamental garden containing fountains and pools and the 13th-century church of Notre-Dame de la Cambre. The abbey buildings now house an art school and the National Geographical Institute. The bois itself is, in fact, the manicured tip of the Forêt de Soignes, Europe’s largest beech forest.

To the West

West of the heart of Brussels is the commune of Anderlecht. One of the greatest men of the Renaissance, Desiderius Erasmus (1469–1536), lived here in a house dating in part from 1468. Maison d’Erasme (House of Erasmus; Tue–Sun 10am–6pm) is an excellent example of 15th-century architecture and features the desk of the philosopher, a Catholic contemporary of Martin Luther, who railed against the strictures of Catholic dogma. The upper floor has books and manuscripts relating to the humanist movement and religious strife. The Renaissance room is home to paintings by Hieronymus Bosch and Dirk Bouts. Across the street is the Béguinage d’Anderlecht (Tue–Sun 10am–noon and 2–5pm), founded in 1252.

Basilique Nationale du Sacré-Coeur

Julian Love/Apa Publications

To the North

Just beyond the petite ceinture in the north is the redeveloped Gare du Nord zone, which now has a number of hotels and bars and a lot of nightlife. Place Rogier ‹ [map], home to restaurants, clubs and shopping malls, is the centre of the activity.

About 2km (1 mile) to the west is the huge Basilique Nationale du Sacré-Coeur (National Basilica of the Sacred Heart; www.basilicakoekelberg.be; Apr–Sept daily 8am–6pm, Oct–Mar daily 8am–5pm; basilica free), in Koekelberg. Begun in 1905 and completed in 1970, this church looks something like a modern take on a Byzantine basilica. The gallery in the dome (charge) affords superb panoramic views.

A short walk east from place Rogier is Le Botanique › [map] (www.botanique.be; exhibitions Wed–Sun noon–8pm), a former botanical garden and glass house of 1826, which was transformed into a cultural centre in the 1980s. The interior is spectacular, with the glass houses – complete with plants – forming a link between the exhibition halls.

Beer museum

Situated close to the Béguinage d’Anderlecht, in a family-owned brewery in rue Gheude, the Musée Bruxellois de la Gueuze (Brussels Museum of the Gueuze; www.cantillon.be; Mon–Tue and Thu-Sat 10am–5pm) celebrates traditional Brussels beers. Perfect on a hot summer’s day.

Heysel

In 1935 and 1958, Brussels hosted major international exhibitions. The events were held in the north of the city at Heysel, where vast exhibition halls were built. Since that time, a number of attractions have developed here. All these can be accessed from the Heysel metro station.

The Parc des Expositions is a fine building erected for the 1935 exhibition. However, it is a structure from the 1958 World Fair that captured the hearts of the people and became one of the most popular symbols of Brussels. The Atomium fi [map] (www.atomium.be; daily 10am–6pm) was built in the shape of the atomic structure of an iron crystal on a scale of 1:165 billion. Constructed of metal spheres linked by tubes, it was created to symbolise the great advances made in the sciences throughout the 20th century. There is a good view of Brussels and the surrounding countryside from the top sphere, a lofty 102m (332ft) high.

The Atomium is adjacent to Bruparck, a large recreational area filled with a variety of activities. Try the Océade for water-based relaxation (http://oceade.be; weekdays 10am-6pm, Sat–Sun and school holidays 10am–9pm), observe the sky at the Planetarium (www.planetarium.be; Mon-Fri 9am-5pm, Sat–Sun 10am-5pm) or watch a film at Kinepolis (www.kinepolis.be). Mini-Europe (www.minieurope.com; mid-Mar–June and Sept daily 9.30am–6pm, July–Aug daily 9.30am–8pm, mid-July–mid-Aug Sat until midnight, Oct–Dec and 1st week Jan 10am–6pm) celebrates European union in a light-hearted way. More than 300 of Europe’s best-known landmarks have been recreated here in miniature (1:25 scale). You can visit a 4m (13ft) high Big Ben and a 13m (42ft) high Eiffel Tower – and press a button that causes the miniature Mount Vesuvius to erupt.

The Royal Estate at Laeken

South of Heysel is the Domaine Royal de Laeken, a vast estate and palace, where the royal family has residences. Although the palace is not open to the public, the magnificent Serres Royales fl [map] (Royal Glass Houses) can be visited during three weeks in April or May. These were built at the behest of Leopold II following his visit to the Crystal Palace in London and other new glass houses of Europe. A monument to this monarch has been erected in the parc de Laeken opposite the palace. Leopold was enthusiastic about architectural styles and building methods – a passion that resulted in the construction of two Asian-inspired structures to the north of the palace. The Pavillon Chinois (Chinese Pavilion), with a carved wooden facade imported from Shanghai, was completed after Leopold’s death in 1910. The pavilion now houses Chinese ceramics. The Tour Japonaise (Japanese Tower), reached by tunnel from the Chinese Pavilion, was designed and built by Parisian architect Alexandre Marcel. Both pavilions used to host exhibitions of antique Asian ceramics but at the time of writing both were closed for renovation. The nearby former storeroom and workshop for the Chinese Pavilion has been renovated as the Musée d’Art Japonais (Museum of Japanese Art), and together the three buildings now constitute the Musées d’Extrême-Orient ‡ [map] (Museums of the Far East; www.kmkg-mrah.be; closed for renovation until further notice).

The Chinese Pavilion at Laeken with a facade from Shanghai

iStock

In nearby Jette, a house on rue Esseghem was home to René Magritte from 1930 to 1954. The Musée René Magritte (www.magrittemuseum.be; Wed–Sun 10am–6pm), not to be confused with the Musée Magritte (for more information, click here), promotes the Surrealist painter’s work.

ENVIRONS OF BRUSSELS

Tervuren

You can reach the suburban Flemish village of Tervuren by taking tram 44 from Montgomery metro station. The route takes you through the commune of Woluwe-St-Lambert, a pretty residential suburb. It plays host to the Musée du Transport Urbain Bruxellois (Brussels Urban Transport Museum; www.trammuseumbrussels.be; Oct–Mar Sat–Sun 1–5pm, other months days and hours vary ), directly on the public transport route, for those who enjoy old trams and trolley buses. The Tourist Tramway (Apr−Oct Sat−Sun, depart 10am, return around 2pm) takes passengers on a tour of Brussels on board a 1930s tram. Old trams or buses also run from the museum to the Cinquantenaire in Brussels and the Soignies forest.

Belgian writer Roger Martin du Gard nicknamed Tervuren ‘the Versailles of Belgium’, and the royal estate here is based on Classical French architectural style and garden design.

In 1897, Leopold II organised a colonial exhibition relating to his expanding lands in the Congo. This proved so successful that a permanent home was built for the exhibits, and an anthropological research centre was instituted. Leopold personally contracted Frenchman Charles Girault, designer of the Petit Palais in Paris, to build the museum. The Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale/Koninklijk Museum voor Midden Afrika (Royal Museum of Central Africa; www.africamuseum.be; closed for renovation at the time of writing) on Leuvensesteenweg is a stunning building surrounded by acres of formal gardens.

Gardens surround the Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale

Julian Love/Apa Publications

The formal gardens surrounding the museum give way to natural forest and parkland. There is a boating lake with lots of bird life, making Tervuren a relaxing spot on a sunny day.

Waterloo

Of the many battles that have taken place on Belgian soil, the Battle of Waterloo 1 [map] was one of the most important. Its impact on European history was long lasting and it proved to be the final rally for Napoleon in his unsuccessful bid to retake France’s leadership. It was during June 1815 that a combined force from Britain, the Low Countries and Prussia began the campaign that would finally destroy the French Emperor. The armies met outside the village of Waterloo on 18 June. By the day’s close the French had been routed, and nearly 50,000 men lay dead or wounded on the battlefield.

Travelling to the site today, one can still see how beautiful the countryside must have been. It has changed with the addition of a modern four-lane highway (the Brussels outer ring road). However, many of the historic buildings have been preserved as museums devoted to the battle, the Waterloo Battlefield (www.waterloo1815.be; Apr–Sept daily 9.30am–6.30pm, Oct–Mar daily 9.30am–5.30pm). La Butte de Lion (Lion Mound), built on the site in 1826 by the government of the Netherlands, marks the spot where their leader, the Prince of Orange, was wounded. The 40m (132ft) mound is topped by a cast iron statue of a lion 4.5m (14ft) in height.

The Lion Mound at Waterloo

iStock

At the base of the mound is a visitors’ centre (free), which presents an audio-visual exhibit of the battle, including the tactics and movements of the opposing forces and a time frame. Nearby, in a separate building, is the Panorama de la Bataille (Panorama of the Battle), a 110m-by-12m (358ft-by-39ft) circular painting executed by Louis Dumoulin in 1913 and depicting scenes of one of the most important events of the battle. Across the road is the Musée des Cires (Waxworks Museum), containing waxworks of the leading military figures involved in the combat.

Strolling around the battlefield, you’ll pass the fortified farms of Hougoumont and La Haie-Sainte, which played crucial roles in the battle. At the southern end of the battlefield is the Dernier Quartier Général de Napoléon (Napoleon’s Last Headquarters), housed in what was the Ferme du Caillou (Caillou Farm), where Napoleon had his headquarters on the eve of the battle. There are a few pieces of memorabilia, including the skeleton of a hussar found at the site.

The British Duke of Wellington had his headquarters at the inn in the village of Waterloo 4km (2.5 miles) to the north. Restored in 1975, it is now home to the Musée Wellington (Wellington Museum; www.museewellington.be; Apr–Sept daily 9.30am–6pm, Oct–Mar daily 10am–5pm), which also has a section depicting the history of Waterloo itself. There is a room devoted to the duke, containing numerous personal effects. Other rooms are given over to the Dutch and Prussian armies, and maps of the battlefield.

Battle of Waterloo

One of many surprising aspects of the Battle of Waterloo is that it did not take place at Waterloo at all, but in rolling fields 4km (2.5 miles) further south, where the road from Brussels, after passing through the Forêt de Soignes, arrives at a low ridge beyond the farm of Mont Saint-Jean. A traveller taking this route on 18 June 1815 would have run into the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and his 75,000 troops here, doing their headlong best to go in the opposite direction.

More surprising by far is that Napoleon, who won an empire through his supreme grasp of the military art, lost it in the end by putting his head down and charging repeatedly uphill in vain, bloody attempts to shift the Duke of Wellington’s 72,000-man army blocking the road to Brussels. ‘If my orders are properly executed,’ Napoleon told his generals before kicking off the carnage, ‘we will sleep tonight in Brussels.’ The superb courage of the French soldiers came near to confirming their emperor’s prediction. Wellington called the contest ‘the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life’.

Excursions

Antwerp

Where Brussels has developed into Belgium’s most important administrative and legislative city, Antwerp 2 [map] (Antwerpen/Anvers), only 48km (30 miles) to the north, has long been the country’s commercial heart. Founded on the River Scheldt (or Schelde), it was an important staging post on the route from England into central Europe and developed into an important trading port by the late Middle Ages. During the Renaissance, Antwerp was one of the cultural capitals of Europe, with the artist Peter Paul Rubens greatly influencing his native town, and philosopher/businessman Christophe Plantin acting as a magnet for advocates of the new sciences.

Walking along the streets of Antwerp today, you quickly become aware of a different atmosphere than that in Brussels. There is a raw energy here, an activity of movement of cargo and goods rather than of paper or files. The city is still one of the largest ports in Europe and the world’s centre of the diamond polishing industry.

Diamond city

Antwerp is the world’s single most important centre for the diamond trade. Most of the cutting, polishing and trading takes place in the Diamond Quarter, where the offices of the Hoge Raad voor Diamant (Diamond High Council) and the Beurs voor Diamanthandel (Diamond Exchange) are located amid a glittering array of jewellery shops.

It is impossible to miss the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal (Cathedral of Our Lady; www.dekathedraal.be; Mon–Fri 10am–5pm, Sat and the day before a religious holiday 10am–3pm, Sun 1–4pm), whose steeple, at 123m (404ft), towers above every other building in the old town. Built during the 14th and 15th centuries, it is a remarkable Gothic creation, the largest in Belgium, and its interior proportions take the breath away. Four Rubens masterpieces grace the cathedral: Raising of the Cross (1610), Descent from the Cross (1614), Resurrection (1612), and Ascension of the Virgin (1626) are colourful and dramatic canvasses that give full rein to the artist’s talent. The largest of the cathedral’s chapels, St Anthony’s, has a lovely stained-glass window, dating from 1503; it depicts King Henry VII of England kneeling with his queen and was created to commemorate a commercial deal made at that time between England and the Low Countries.

Cathedral of Our Lady

iStock

A stroll around the outside of the cathedral also reveals a few surprises. The area acted as a commercial centre as well as a religious site and huddling around the base of the structure are buildings as old as the church. These are now cafés, bars and souvenir shops. In front of the cathedral is the small Handschoenmarkt with its cafés. Look out for an ornate well, the Putkevie, topped by a statue of Brabo, Antwerp’s hero.

Walking west towards the river first takes you past the Vlaeykensgang, a restored 16th-century courtyard, with an entrance off Oude Koornmarkt. From here, cross over to the Grote Markt. This square, like the Grand-Place in Brussels, epitomises the power of trade and commerce throughout the history of the city. The mansions that line the Grote Markt were built for the trades’ guilds or corporations, which wielded great power during Antwerp’s heyday. The most ornate is No. 7, De Oude Voetboog (House of the Old Crossbow). At the centre of the Grote Markt is a 19th-century fountain, with a depiction of Brabo wielding the severed hand of the giant Antigoon.

Antwerp’s Grote Markt, with the Brabo fountain at its centre

iStock

Brabo – Antwerp’s Hero

Legend tells of how the citizens of Antwerp were being terrorised by an evil giant, Antigoon, who extracted tolls from those who wanted to cross the river. If travellers could not pay, Antigoon would cut off their hands in punishment. Young Silvius Brabo, a Roman soldier, was brave enough to stand up to the monster and beat him, cutting off his hand as a sign of victory and throwing it into the River Scheldt. His heroics not only saved the whole town from tyranny but may also have given the town its name – hand werpen (hand-throw).

Antwerp’s Town Hall

On the square’s west side, the Stadhuis (Town Hall) was built in the 1560s under Cornelis Floris de Vriendt. It has a sombre balance in its design, with lines of faux columns atop a ground floor of arched doorways. The central section, added in the 19th century, is Flemish in its architectural adornment. Coats of arms of local duchies grace the facade, and a central alcove displays a statute of Our Lady, the protector of the city. Inside, the corridors have dioramas depicting historical council meetings and activities in the chambers. To the south is Groenplaats, lined with shops and cafés and sporting a statue of Rubens.

After exploring Grote Markt, head towards the river via the Gothic Vleeshuis (Butchers’ Hall). Built in the 16th century, it looks like a church with a fine facade and spires, but was a guild house and trading hall. The building now houses the city’s museum of music, the Museum Vleeshuis (Vleeshouwersstraat 38–40; www.museumvleeshuis.be; Thu–Sun 10am–5pm).

When you reach the river, you can take a boat trip (Flandria; www.flandria.nu) downstream to the busy modern harbour. Boat trips leave regularly in summer from the dockside at the Steen. This 13th-century castle is the oldest remaining structure in Antwerp, and legend has it that it was the home of Antigoon the giant. It later became a prison, and then until 2008, housed the Nationaal Scheepvaartmuseum (National Maritime Museum), which has since moved to the MAS/Museum aan de Stroom (Museum in the Stream; www.mas.be; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm, last Thu of the month until 9pm, Apr–Oct Sat–Sun 10am−6pm), downriver at the Bonapartedok harbour.

Printing and art

Walk south of Grote Markt towards the Plantin-Moretus Museum (www.museumplantinmoretus.be; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm) in Vrijdagmarkt. Christopher Plantin was one of the most important craftsmen-businessmen of the late Spanish Empire in the Low Countries. His house and neighbouring printing press offer an insight into the man and the philosophy of this time of great expansion and learning, concentrating on writing and printing. Seven antique printing presses are still in working order, and there is a collection of rare manuscripts. Plantin’s family sat for portraits that are displayed on the walls; many of the portraits were painted by Rubens.

The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen (Royal Fine Arts Museum Antwerp; www.kmska.be) on Leopold de Waelplaats is closed for renovation until 2020, but its collection can be seen at other galleries in the city (see website for details). A collection of beautiful art of the Rubens school can be found in Sint-Pauluskerk (St Paul’s Church; http://topa.be; Apr–Oct daily 2–5pm; free) on Sint-Paulusstraat. The church was part of a Dominican monastery and was constructed during the mid-16th century in the late-Gothic style. The interior is decorated with fine wood panelling surpassed only by the majesty of 15 large canvasses depicting the Mysteries of the Rosaries, painted by 11 different master painters.

Rubens House

The Rubenshuis (Rubens House; www.rubenshuis.be; Tue–Sun 10am–5pm; last Wed of the month free) at Wapper 9–11, located just off the main shopping street, Meir, is today surrounded by modern shops and cafés, although it still gives an impression of the immense wealth and influence of arguably the best-known Belgian artist. He used the money earned from painting portraits of European royalty to build a large and substantial home for his family – eight children by two wives – and a studio for himself in 1610. The family lived in a Flemish-style wing of the house. It is austerely furnished, but look out for a self-portrait of the artist hanging in the dining room. Contrast this family wing with the studio, which was decorated in the then-fashionable Baroque style. Here you will find Rubens’ extensive collection of Greek and Roman sculpture.

Rubenshuis

iStock

Rubens had a hand in the design and adornment of the 17th-century Sint-Carolus Borromeuskerk (St Charles Borromeo Church; www.carolusborromeus.be; Mon–Sat 10am–12.30pm and 2–5pm; Sun masses only; church free, Lace Room, 10am-12pm and 2-4pm), in Hendrik Conscienceplein, east of the Grote Markt. The artist, along with members of his family, is buried in the 16th-century Sint-Jacobskerk (St James’s Church; http://topa.be), in nearby Lange Nieuwstraat, inside which there are a number of his paintings, and a portrait of Rubens.

Inside Antwerp’s Sint-Carolus Borromeuskerk

iStock

Works by Rubens are also in evidence in the Mayer Van den Bergh Museum (Tue–Sun 10am–5pm; www.mayervandenbergh.be) on Lange Gasthuisstraat, and although Pieter Bruegel was a resident of Brussels, there are several of his works here, including his earliest known painting, Twelve Proverbs, and his sombre view of war Dulle Griet (Mad Meg). The museum is based on the collection of Sir Fritz van den Bergh and includes a large collection of sculpture, tapestries and ceramics from the 12th to the 18th centuries, in addition to a wide range of art.

Museum of Modern Art

Known as M HKA, the Museum voor Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen (Antwerp Museum of Modern Art; www.muhka.be; Tue–Sun 11am–6pm, Thu until 9pm) occupies a former warehouse in Antwerp’s old port, on Leuvenstraat, close to the Scheldt. Behind the warehouse’s original Art Deco facade, a collection of cutting-edge Belgian and international art is expanding to fill the enormous interior.

In the newer part of town (c.19th century) across the ring road, a boulevard skirts the old town. Browse in the modern stores lining Meir, a pedestrian-only area. As Meir becomes Leystraat, the buildings take on a very ornate style, flanking Teniersplein with its statue of the artist David Tenier (a relative of Bruegel). Cross Frankrijklei and walk towards the railway station along Keyserlei. To your left is De Vlaamse Opera (Flemish Opera House), which opened in 1907.

Diamonds galore

To the right of Keyserlei is the diamond district where 80 percent of the world’s raw diamonds and 50 percent of its cut diamonds are traded. The streets here are filled with jewellery shops selling items from only a few euros to individual pieces worth hundreds of thousands. If you want to know more about this most precious of minerals, head to Diamondland at Appelmansstraat 33a (www.diamondland.be; Mon–Sat 9.30am–5pm). This diamond showroom and polishing house features films and polishing exhibitions about the trade.

Antwerp Station was designed in French Renaissance style and opened in 1905. Its fine dome is reminiscent of a cathedral, and the station’s proportions bear testament to the importance of investment in the rail industry at the end of the 19th century.

Beyond the station is Antwerp Zoo (www.zooantwerpen.be; daily 10am–dusk), founded in 1843 on 10 hectares (25 acres) of land.

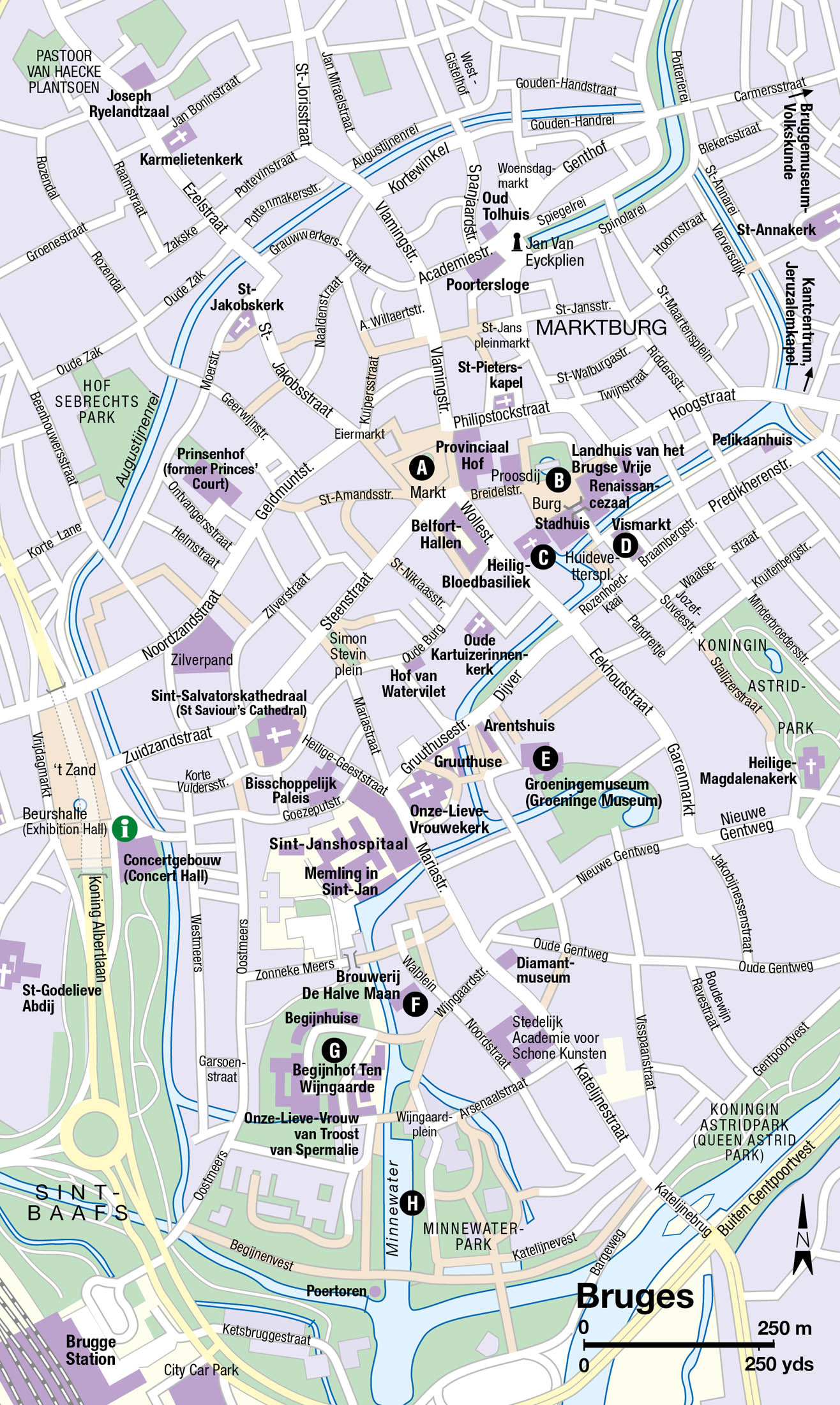

Bruges

In the Middle Ages this small Flemish city 3 [map], known as Brugge in Dutch, was one of the most influential in northern Europe, with a thriving economy based on trade with Europe and England. It was the leading city for textile and tapestry production and was a major trading town of the Baltic-based Hanseatic League. Cargoes of wool, furs and spices passed through its port, which was connected to the sea via the Zwin inlet. In 1384, the Burgundian Philip the Good made Bruges the capital of his growing realm, and artists Hans Memling and Jan van Eyck were at the centre of a royal court that was one of the most splendid in Europe. But the city lost its influence as early as the 15th century. Cheap textiles from England flooded the market, and the Zwin inlet began to silt up. Bruges became land-locked and in time was all but forgotten.

However, it was the sudden loss of prestige and influence that has helped to make Bruges one of Europe’s most popular tourist destinations. The town was never redeveloped, and today it still has an almost complete medieval historical area. Most of its canals remain, and a stroll along the narrow streets offers picture-perfect views.

Tours by Carriage and Boat

Bruges is eminently walkable, but before you start your own exertions take a tour of the streets by horse-drawn carriage or along the small network of canals by boat. If you have the time, try both, as they offer contrasting experiences in different parts of town.

Along the canals

A tour through the canals of Bruges in an open boat is a delightful experience, and the view from this splendid vantage-point is memorable. All boats cover the same route and depart from several landing stages around the centre (Mar–Nov 10am–6pm).

A ride around Bruges

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The Markt

Bruges’ two town squares are linked by a short street (Breidelstraat). The Markt A [map] is larger of the two, and the commercial centre of the town. In the middle of the square stands a 19th-century sculpture, a tribute to Jan Breydel and Pieter de Coninck, the leaders of a 1302 revolt against French overlords. Over on the southeast side of the square stand the Belfort-Hallen (Covered Market). The Belfry houses the Bruggemuseum-Belfort (www.visitbruges.be/musea; daily 9.30am–6pm). Built in the 13th century, the Belfry was later extended, and the clock was added in the 15th century. Climb to the top, 366 steps and 84m (276ft) up, for a panoramic view. Part of the way up around the steep stairwell, you pass the 47-bell carillon. Inside the Belfry was the town treasury, and such were the riches of the town that they could only be accessed with nine keys. The adjacent 19th-century Provinciaal Hof (Provincial Palace) is the seat of the West Flanders provincial government.

View from Rozenhoedkaai, in Bruges, across to the Belfry

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

The Burg and Town Hall

The Burg B [map] is the smaller of the two squares, and the oldest, dating to medieval times. It was named after the original castle of Bruges (which is no longer standing). Each building on the Burg reveals its own beauty and together they make one of the most coherent, sequential architectural statements in Europe. On the south side of the square is the Stadhuis (Town Hall), a Gothic masterpiece built from 1376 to 1420. Its ornate facade has a wealth of detail, adorned with statues of the counts of Flanders, family crests and scenes of daily life. Inside, in the Bruggemuseum-Stadhuis (www.visitbruges.be/musea; daily 9.30am–5pm), there is even more evidence of civic pride, with guild pennants hanging from the ceiling. The Gothic Hall on the second floor has a magnificent vaulted wooden ceiling decorated with gilt.

To the right of the Stadhuis is the Landhuis van het Brugse Vrije (Palace of the Liberty of Bruges). The mansion, which houses the Brugse Vrije museum (www.visitbruges.be/musea; daily 9.30am–5pm), is an interesting amalgam of architectural styles. It is renowned for its ornate chimneypiece of marble, alabaster and oak, dating from 1531, in the Renaissancezaal (Renaissance Hall). At its centre is a statue of Emperor Charles V, surrounded by other members of the Habsburg dynasty. At the rear of the complex are the remains of a 16th-century building. The facade in front of the square is 18th century. Between the Stadhuis and the Landhuis van het Brugse Vrije is the Oude Civiele Griffie (Old Recorder’s House), which was completed in 1537.

The Belfry is the signature landmark of Bruges

Glyn Genin/Apa Publications

Basilica of the Holy Blood

West of the Stadhuis is the entrance to the city’s most important religious building. This is the Heilig-Bloedbasiliek C [map] (Basilica of the Holy Blood; www.holyblood.com; daily 9.30am–12.30pm and 2–5.30pm, Nov–March closed Wed; church free, charge for treasury), whose facade was completed in 1534.

Inside the Heilig-Bloedbasiliek (Basilica of the Holy Blood)

iStock

Inside, there are two small and richly decorated chapels. The lower chapel is 12th-century Romanesque, while the upper one is 16th-century Gothic in style, with 19th-century alterations. It is in a side room of this upper chapel that the relic that gives the basilica its name is kept. When the Flemish knight and count of Flanders Dirk of Alsace returned in 1150 from the Second Crusade, he is said to have brought back a phial containing a fragment of cloth stained with a drop of Christ’s blood. The blood was said to have turned liquid on several occasions, and this was declared miraculous by Pope Clement V, and Bruges became a centre of pilgrimage.

In 1611, the archdukes of Spain presented the church with an ornate silver tabernacle in which the phial is now stored. The phial leaves the side chapel once per year on Ascension Day in May, when it is carried through the streets of Bruges in the Procession of the Holy Blood, one of the most elaborate processions in Belgium. The gold-and-silver reliquary used to transport the phial can be seen in a small treasury just off the chapel.

Opposite the Stadhuis, near the basilica, is the Proosdij, formerly the palace of the bishops of Bruges.

Groenerei and Huidenvettersplein

Take the route through the narrow archway between the Stadhuis and the Oude Civiele Griffie. You’ll cross one of Bruges’ network of canals to Groenerei (Green Canal) and see the covered Vismarkt D [map] (fish market) just ahead. A short walk to the left takes you to the Pelikaanhuis (Pelican House), easily identified by the emblem of the bird above the door. Built in 1634 at the point where the canal curves to the right, this was one of many almshouses in the city. There are several boarding points for boat tours along the canal-side here, though you may have to queue.

At the diminutive square of Huidenvettersplein, several houses are huddled at the water’s edge, with a view of the Belfry rising behind and weeping willows softening the red brick. When the tour boats pass on the canal, you can hardly fail to be enchanted.

Museum of Fine Arts

The street of Dijver runs alongside Groenerei. Here you will find a number of major museums. First is the Groeningemuseum E [map], the city’s museum of fine arts (www.visitbruges.be/musea; Tue–Sun 9.30am–5pm), which displays a fine collection of Flemish masters including the work of Jan van Eyck, particularly his Madonna with Canon George Van der Paele, of Hieronymus Bosch and Gerard David. Works of later Belgian artists such as René Magritte are also on display. Take a walk around the gardens. The whole vista is typically Flemish, with its low-rise, cottage-style white buildings with red tile roofs.

Flemish Masters

A group of early Flemish artists, based mostly in Bruges and Ghent, have had their work handed down to us under the banner of the Flemish ‘Primitives’. The word is used in the sense of primary (being first), and indeed the luminous, revolutionary work of Jan van Eyck (1385–1441), whose Adoration of the Mystic Lamb is in Ghent’s Bavo’s Cathedral, could scarcely be thought of as primitive. Nor can that of his contemporaries Rogier van der Weyden (c.1399–1464), Hans Memling (c.1430–94) and Petrus Christus (c.1410–72), who shared Van Eyck’s fondness for realistic portrayals of human and natural subjects.

Later, the focus of Flemish art switched to Antwerp and, to a lesser degree, to Brussels. The occasionally gruesome works of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525–69), the sensuous paintings of Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and the output of Rubens’ students Jacob Jordaens (1593–1678) and Antoon van Dyck (1599–1641) cemented the Flemish connection with the finest art of its day.

In the 18th-century Arentshuis (www.visitbruges.be/musea; Tue–Sun 9.30am–5pm) are housed elements of the Groeningemuseum’s collection, and an extensive collection of British Arts and Crafts exponent Sir Frank Brangwyn, who was born in Bruges and bequeathed his work and collection to the city when he died in 1956. As a student of William Morris, Brangwyn is an important link to later artistic movements.

An adjacent palace once belonged to a powerful Burgundian-era family, the lords of Gruuthuse, so called because the original owners had the right to tax ‘gruut’, the basic mash of herbs and spices used in the brewing process. Erected in the 15th century, the palace has twice housed fugitive English kings – Henry IV in 1471, and Charles II in 1656. In the garden (free), a romantic brick bridge crosses one of Bruges’ narrower canals, offering yet another picture opportunity. You will also find Rik Poot’s modern sculpture, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, gracing the outer courtyard.

The Gruuthuse

iStock

The rooms of the mansion display a wealth of daily articles including furniture and utensils. The huge kitchen is particularly interesting – it looks as if the 15th-century cook has just stepped out of it to do the daily shopping.

At the end of Dijver is the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk (Church of Our Lady; Mon–Sat 9.30am–5pm, Sun 1.30–5pm; some parts of church free; charge for museum), an imposing church that has a 122m (400ft) brick tower – the second highest in Belgium, after Antwerp Cathedral’s. Inside the church you will find the gilded tombs of duke of Burgundy Charles the Bold and his daughter Mary of Burgundy. Mary’s death at the age of 25 brought the Burgundian period of Belgian history to an end. The Church of Our Lady also displays a sculpture of the Madonna and Child by Michelangelo, the only one of his works to be exported from Italy during the artist’s lifetime.

Hans Memling Museum

Opposite the entrance to the church, through an archway, is Sint-Janshospitaal (St John’s Hospital, refurbishment of the permanent exhibition scheduled for 2019). Dating from the 12th century, it is the oldest building in Bruges. It remained in use until the 19th century. In the old hospital church you will find Memling in Sint-Jan (www.visitbruges.be/musea; Tue–Sun 9.30am–5pm), which is devoted to the work of the German-born master Hans Memling, who settled in Bruges. Although the collection is not extensive, each piece is particularly fine. Look for the Mystic Marriage of St Ursula; the detail of this painting makes it one of Belgium’s national treasures.

St John’s Hospital, the oldest building in Bruges

iStock

Walk south down Mariastraat, with its selection of chocolate and lace shops. A left turn at Wijngardstraat leads to the Begijnhof, but before this, look for the small square of Walplein and the brewery Brouwerij De Halve Maan F [map] (www.halvemaan.be; guided tours Apr–Oct daily 11am–4pm, Sat until 5pm, Nov–Mar daily 11am–3pm, Sat until 5pm, Sun until 4pm), which has been in operation in the city since 1546. A tour of the present brewery, opened in 1856, takes around 45 minutes, and ends with a taste of Bruges’ own Straffe Hendrik beer.

The Begijnhof

The Begijnhof G [map] at Bruges (or to give it its full name, the Prinselijk Begijnhof Ten Wijngaerde/Princely Béguinage of the Vineyard) was founded in 1245 by countess of Flanders Margaret of Constantinople and was active in providing security for lost and abandoned women until the 20th century. The circular collection of white painted buildings dating from the 17th century – an oasis of solitude – is now home to a community of the Benedictine order. Just before the main entrance is an open area with a pretty canal and a range of restaurants. The horse-drawn carriages turn around here on their tours. You’ll find a water fountain here for them, decorated with a horse’s head.

From the fountain, it is only a couple of minutes walk to the Minnewater H [map] (Lake of Love) and a picturesque park. Minnewater was originally the inner harbour of Bruges, before the outlet to the sea silted up. Today, you can see the 15th-century gunpowder house and scant remains of a protective wall. The open water is a haven for birds, including swans.

The old quaysides

The main canal that served the centre of the old town entered from the north. Today this terminates at Jan van Eyckplein, with a statue of the artist, just a couple of minutes away from the Markt. In the square, you can still find fine buildings lining what were once the busy quaysides of Speigelrei and Spinolarei. The 15th-century Oud Tolhuis (Old Toll House) is where taxes on goods entering and leaving the city were collected. Today it is home to the West Flanders Provincial Archives. Nearby is the Poortersloge (Burghers’ Lodge), a kind of gentlemen’s club for the wealthy businessmen of Bruges’ golden age.

Located at Balstraat 16, east of the central canal, is the Kantcentrum (Lace Centre; www.kantcentrum.com; Mon–Sat 9.30am–5pm), a museum and workshop in the 15th-century Jeruzalemgodshuizen (Jerusalem Almshouses). Fine examples of the craft of lace-making, and demonstrations by lacemakers, can be seen.

Nearby on Peperstraat stands the 15th-century Jeruzalemkapel (Chapel of Jerusalem; http://adornes.org; Mon–Sat 10am–5pm), built by the wealthy Adornes merchant family. It was inspired by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, which two of the family’s members had visited. Farther along Balstraat, you come to the city’s folklore museum, the Volkskundemuseum (www.visitbruges.be/musea; Tue–Sun 9.30am–5pm), affording a glimpse into life in Bruges in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before tourism in the city took off.

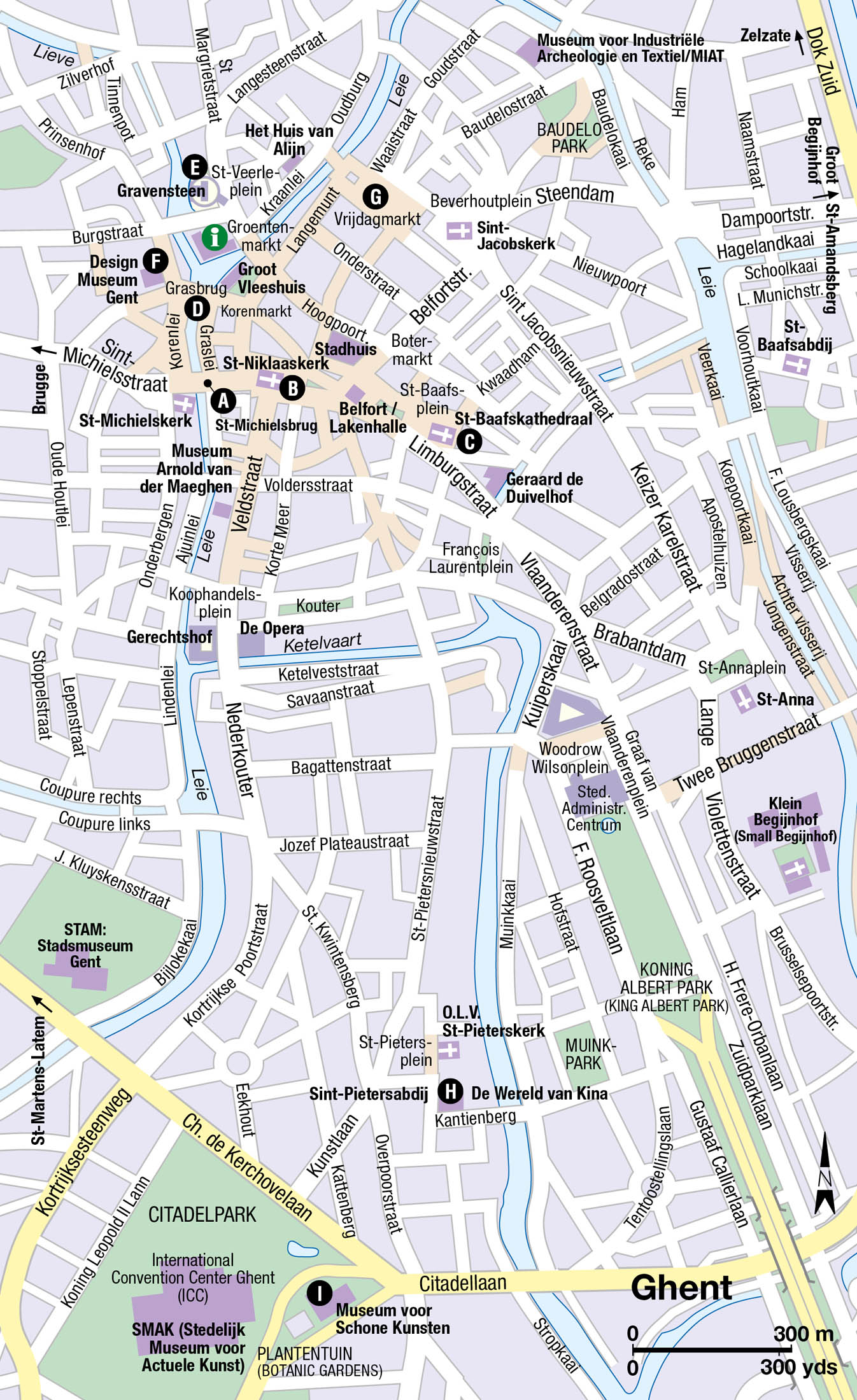

Ghent

In the 12th century, Ghent 4 [map] (Gent in Dutch and Gand in French) was one of the largest cities in Europe, thriving on its trade in textiles and its position at the confluence of the Leie and Scheldt (Schelde) rivers. Today, it is thriving as a modern commercial town. Thanks to its university, it has a young population, which gives it a vibrancy not felt in Bruges. Ghent also has many interesting historic attractions to enjoy. Much of the town centre is traffic-free, except for the tram services, which adds to the enjoyment of walking. Perhaps the best place to start your tour is at Sint-Michielsbrug A [map] (St Michael’s Bridge), spanning the River Leie just west of the old town. To the left are the old quaysides of Graslei and Korenlei, and beyond them is the medieval castle, the Gravensteen. Three of Ghent’s landmarks – Sint-Niklaaskerk, Belfort and Sint-Baafskathedraal – lie ahead.

Graslei quayside, Ghent

iStock

The Church of St Nicholas

The Sint-Niklaaskerk B [map] (church of St Nicholas; Mon 2–5pm, Tue–Sun 10am–5pm) was built from the 13th to the 18th centuries and is therefore an amalgam of architectural styles. Beyond the church is the Belfort (Belfry; daily 10am–5.30pm), completed in 1380. You can take a lift to the viewing platform 91m (298ft) above the town, for tremendous views.

Around the Belfry is the Lakenhalle (Cloth Hall), completed in 1441. Both the Belfort and Lakenhalle are on Emile Braunplein, adjacent to Botermarkt (Butter Market), a major meeting place in centuries gone by. In the 16th century, it was decided to build the new Stadhuis (Town Hall) on the north side of the square. Work was halted in 1639 and only recommenced as the 18th century dawned. You will notice that the building has one Renaissance facade facing Botermarkt, a Baroque one opposite Hoogpoort and a Rococo facade on the Poeljemarkt side. In the ornate interior of the Pacificatiezaal (Pacification Room) the Pacification of Ghent, a treaty aimed (fruitlessly) at ending the religious wars in the Low Countries, was signed in 1576.

St Bavo’s Cathedral

The third spire to be seen from Sint-Michielsbrug belongs to Sint-Baafskathedraal C [map] (St Bavo’s Cathedral; cathedral: Apr–Oct Mon–Sat 8.30am–6pm, Sun 10am–6pm, Nov–Mar Mon–Sat 8.30am–5pm, Sun 10am–5pm; cathedral free, admission fee for crypt and Mystic Lamb chapel; Apr-Oct 9.30am-5pm, Nov-Mar 10.30am-4pm for more information, click here). This granite-and-brick building is also a mixture of architectural styles, with a chancel dating from the 14th century, a nave from the 15th century and a transept from the 16th century.

St Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent

iStock

The art inside the cathedral represents some of Belgium’s greatest cultural treasures. To the left of the main entrance is a chapel containing what has become known as the Ghent Altarpiece, a Jan van Eyck masterpiece called The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (1432). Here, Van Eyck achieved reality through painstaking attention to every detail, breaking away from the medieval stylised form. Other masterpieces include The Conversion of St Bavo by Rubens and a work by Frans Pourbus, Christ Amongst the Doctors, which has many luminaries of the time painted as onlookers in the crowd.

Rubens’ The Conversion of St Bavo

Paul Hermans

Korenlei and Graslei

Just to the left of Sint-Michielsbrug, Korenlei and Graslei D [map] once formed the main harbour of Ghent, known as Tussen Bruggen (Between the Bridges). Here you can find some of Ghent’s finest old buildings. Both sides of the river are equally beautiful, but on Graslei, look out particularly for the Gildenhuis van de Vrije Schippers (House of the Free Boatmen), built in 1531, and Het Spijker (1200), which has been tastefully developed into a bar and eatery. Korenlei rivals its neighbour with the Gildenhuis van de Onvrije Schippers (House of the Tied Boatmen), a Baroque masterpiece dating from 1739, and De Zwane, a former brewery of the 16th century.

Gravensteen

iStock

Gravensteen

Walk north along the river, and as it splits, you will see up ahead the grey walls of the Gravensteen E [map] (Apr–Oct daily 10am–6pm, Nov–Mar daily 9am–5pm). The outline that the Gravensteen presents is the stuff of fairytales: crenellations and turrets, tiny slits for archers to fire their arrows, and a moat to stop invaders. The castle was the seat of the counts of Flanders and from its construction in 1180 it represented their huge power and wealth. Inside you can visit their living quarters, the torture chamber and dungeons, where grisly instruments are on view.

Just to the west of the Leie, the Design Museum Gent F [map] (www.designmuseumgent.be; Mon-Tue and Thu-Fri 9.30am–5.30pm, Sat-Sun 10am–6pm) occupies a 1755 mansion with a central courtyard. The rooms display interior design and furnishings up to the 19th century. A separate wing contains modern furniture.

Patershol