The General Assembly

“If people aren’t being respectful of others’ identities, or are speaking from a limited perspective, that will be added into the conversation. People will be called out on it”.

—DiceyTroop, General Assembly Twitter reporter

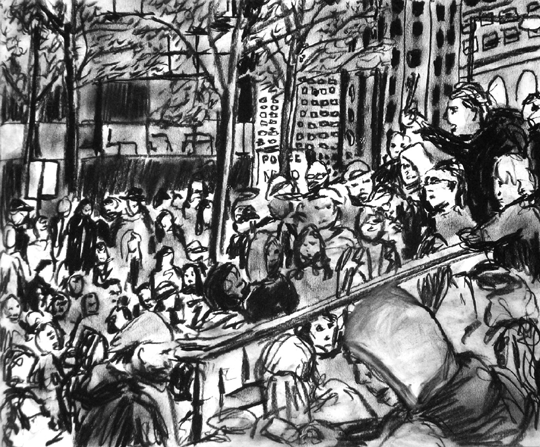

The General Assembly, an extraordinary nightly display of consensual democracy in action, soon became one of the defining experiences of Occupy Wall Street. No one attending its meetings, generally held at 7 p.m. each evening in the shadow of the big red statue at the east end of Zuccotti, could fail to be impressed, indeed often moved, by the spirit of community engendered by the GA, as it came to be known.

Participants, on some evenings numbering in the thousands, sat on the steps running down from Broadway, or huddled together at their foot, on the paving of the park. Behind them, activists gathered in serried rows, some on the low walls of the flower planters, others stretching off into the copse of small trees that forms a parasol over the interior of the park. The meeting was addressed from the steps, with speakers distinguished only by the fact they were on their feet, surrounded by the GA’s facilitators, bellowing their words in the steady, rhythmic cadence that the “people’s mic” demands.

The diversity of the crowd was immediately apparent. Those sleeping in the park, with the grimy demeanor and clothing that signaled the rigors of camping out, stood next to smartly attired office workers, who had apparently dropped by on a detour from their evening commute; older activists, dressed as if they had just returned from hearing Country Joe play Woodstock, sat crammed next to college students who dressed, well, pretty much the same way.

What unified this disparate throng was a tangible sense of solidarity, a commitment to the cause of the occupation, but also an evident commitment to each other. It was not unusual for food, packets of biscuits or pretzels, or bottles of water to be passed hand-to-hand around the rows, shared by strangers who had just become comrades. The crowd was united also by a gentle but firm resolve to respect the rights of others, to space, to be heard, to be whoever they were.

This respectfulness extended to the facilitators running the meetings, whose patience and good nature in the face of often arcane and protracted procedural negotiations bordered on the superhuman. Identifying themselves only by their first names, and rotating responsibility, both within each meeting and on different nights, their effort not to appear in any way as “leaders” seemed admirable, if sometimes less than convincing. Running a meeting of hundreds or thousands, without amplification and under rules which many present found unfamiliar, required considerable charisma and eloquence, qualities that the young people facilitating the GA evidenced in spades.

Those who spoke at the GA often did so with barely suppressed emotion. Hearing one’s words echoing off the bankers’ towers surrounding the park as they were repeated, sometimes up to three times, by expanding concentric circles of the crowd, was evidently an experience both strange and profoundly moving. At the GA on the night following the eviction of the tents from the park, more than one speaker openly expressed love for the assembly, a declaration that would have surely seemed saccharine and disingenuous in more conventional gatherings, but here was received, without embarrassment, as an authentic act of communion.

Formally, the GA served a prosaic function: it was the decision-making body of the action and the forum through which organizers made sure that the needs of those participating were met—reports from groups dealing with food, legal and medical assistance, sanitation, and security took up much of the agenda. But the GA also provided a place for protesters to air grievances, decide on direct actions, and debate movement strategy, among other things. Although its use of the people’s mic and consensual decision-making often proved frustratingly clumsy and time-consuming for resolving detailed issues, as a means of bonding and establishing the broad principles of the action, the GA proved highly effective.

The facilitation working group took responsibility for preparing the agendas, calling the meeting to order, and quieting a sometimes distracted crowd. The facilitators were trained prior to hosting their first GA and so were familiar with the techniques that enabled them to let all opinions be heard in the most respectful and efficient way. In order to prevent the emergence of an entrenched leadership, facilitators were not allowed to lead two meetings in a row and so rotated dates and responsibilities. New facilitators were paired with those who were more experienced so that a basic skill level was maintained throughout.

To the uninitiated, the GA could sometimes seem overwhelming, unfocused and unproductive. Even some of those who had participated in previous actions, and were thus familiar with the precepts of participation, consensus, and transparency that underpinned the running of the GA, were surprised to see the model attempted in a public space with such large numbers present. To help address the problems this inhered, facilitators took the first few minutes of each meeting to explain the mechanisms through which the GA operated.

First were the hand signals that made it possible for the crowd to communicate en masse with each other and with the facilitators. The most frequently used of these gestures is called twinkling. A wiggling of the fingers with either one or both hands raised, twinkling originated as a symbol in American Sign Language to express applause. Over the course of OWS, its use evolved and expanded as Marina Sitrin, whose experience as a facilitator stretches back to the 1999 Seattle antiWTO mobilizations, explained, “. . . by twinkling you see the reaction of the person next to you. Are they happy or not? Are they liking it? The language has started to change so now when people talk about twinkling, it’s not silent applause, it’s do ya like it? Now there’s the temperature check, so there’s twinkling in the middle and twinkling down below. Twinkling with your fingers straight in front of you means I’m on the fence. This is the language people use, I’m in the middle. And then wiggling your fingers in a downward direction is I’m not liking it, I’m not feeling it. The first time I’ve ever seen it [the temperature check] is in Occupy Wall Street and I’ve been in a lot of big democratic spaces. I like it because it’s a way of shouting out, without the shouting.”

A range of other hand gestures is commonly used at GAs: Point of process is signaled by forming a triangle with the thumbs and index fingers. It indicates that a transgression of the agreed procedures of the meeting has occurred, perhaps by someone speaking out of turn or off-topic, and constitutes a request that the facilitators move the discussion back on track. Point of information involves raising one hand with an extended index finger and is used to convey that the signaler has an important fact related to the matter under consideration. Clarification is made by curling one hand into a C shape, and indicates that a person is confused and needs to ask a question to better understand the discussion. And the wrap it up signal is made by a rolling motion of the hands and is meant to convey, in a loving and respectful way of course, as the facilitators always stress, that the person speaking should draw their comments to a close and step back so others have a chance to talk.

Of all the signals used in the GA, the block is the most consequential. It is expressed by the crossing of arms over one’s chest and it indicates a serious moral or practical objection to the proposal. Facilitators regularly caution against overuse of the signal, explaining that it is an extreme measure, indicating that the objector will leave the group if her or his concerns are not addressed. Typically, the person making the block will explain the reasoning behind their objection and offer a “friendly amendment,” designed to make the proposal under discussion something that can be supported.

Like many other aspects of OWS procedures, the use of hand signals has a long history. According to Marina, “. . . the tools and language [that OWS uses] originate with the Quakers. We’re talking about generations, the anti-war movement, the feminist movement; a lot of different social movements in the U.S. have used different forms of consensus that include [facilitation] tools.” Marina also pointed out that, because they are silent, the hand gestures were particularly useful in large assemblies where clapping or cheering would use up time that could be otherwise devoted to the business of the meeting, a consideration of particular importance for proceedings being conducted at the tortoise tempo of the people’s mic.

The other major structural component of the GA is the use of the progressive stack to order crowd comments on proposals. During the early days of the GA, when it was being held in Tompkins Square, the core organizing group realized that, despite their openness and desire for diversity, the majority of those taking the floor remained stubbornly white and male. As a response to this inequity, a decision was made to give preference to those groups such as women and people of color whose voices are typically less often heard. Orchestrating progressive stack is part of the role of the stack-taker who recognizes those wishing to speak to the GA. “If people aren’t being respectful of others’ identities, or are speaking from a limited perspective, that will be added into the conversation. People will be called out on it. The process makes it easier to do that,” explains DiceyTroop, a member of the press team who has live-tweeted GA meetings.

This sensitivity to inequities that exist in society at large is part of a fundamental unease on the part of OWS organizers towards any form of hierarchical structure. Another feature of the introductory segment of the GA is an explanation of the idea of step-up/step-back. This concept encourages those requesting time to speak to consider whether they might “step up” by recognizing their relatively privileged role in society at large and cede the floor, or “step back,” to allow someone from a group with traditionally less opportunities to have their voice heard.

The hand signals, progressive stack and step-up/step-back are key components of how GA facilitators try ensure genuine democracy at the meetings. Having explained their use at the outset of proceedings they then introduce the agenda for the meeting. On most evenings this is a mix of proposals, working group report backs, and announcements. During this section of the meeting, those in the crowd are discouraged from any lengthy exposition of their opinions and business moves at as brisk a pace as the people’s mic, points of information, requests for clarification, amendments, and temperature checks allow. The chance for those present to speak off the cuff comes towards the end of the GA with a session called, appropriately enough, the soapbox. This period of the meeting, perhaps unsurprisingly, can stretch for long hours into the night, with often a dwindling audience, but the same rules of affirmative speaking and respect for the rights of others to be heard apply.

Over time the procedures of the GA have become more sophisticated. Latterly, for example, working groups bringing proposals to the GA are required to post them on the OWS Web site 48 hours ahead of time so that people can prepare their responses and plan their attendance to coincide with items they consider of particular importance. Furthermore, the GA is now no longer the only decision-making body within OWS: The formation of a Spokes Council, consisting of representatives from each of the working groups, was latterly agreed on so that the movement could more easily coordinate financial and legal decision making.

The GA does not always function smoothly. Its proceedings can easily be derailed by people making unnecessary calls for a mic check or superfluous points of information. Though the use of the block is generally restrained, it can on occasion throw otherwise broad consensus into chaos. Moreover, the fact that the meetings are held publicly, open to anyone who cares to show up, and with the intention of giving voice to everyone present who wishes to speak, poses a number of problems. The meetings can be populated by people entirely unfamiliar with OWS proceedings or, worse, unsympathetic to its aims. The crowd varies in both size and character from one meeting to the next, most of those present are not attending consecutive meetings and for some this will be their first and only visit. Especially since the eviction, the issue of who is participating in the GA has become particularly acute. Anyone carrying a large bag, a group that includes many of the original occupiers who stayed overnight as well as some of the homeless, has been denied entry to the park by the police and thus prevented from attending the meetings.

In the face of difficulties intrinsic to the GA process, facilitators and organizers have continued their work to make the meetings more accessible. Emergency proposals can be taken at the GA even though they have not been circulated in advance, minutes of proceedings are posted to the OWS Web site, and a live account of what’s happening is conveyed in real time by the press team using social media. DiceyTroop is just one of those who have taken responsibility for live-tweeting the GAs and Spokes Councils. Live streaming via video blogs such as The Other 99% also helps to get the word out.

Debates about how to refine and develop the process continue apace and important questions remain as to whether the General Assembly model can maintain a genuinely democratic movement as it develops beyond the first flush of enthusiasm of a new movement. But for those lucky enough to have been present in Zuccotti during those heady evenings of early fall 2011, the OWS General Assembly has provided a trove of inspiring and unforgettable memories, and a pointer to a new way of doing politics.