IT OCCURRED TO ME early on in my association with wolves that I was distrustful of science. Not because it was unimaginative, though I think that is a charge that can be made against wildlife biology, but because it was narrow. I encountered what seemed to me eminently rational explanations for why wolves did some of the things they did, only to find wildlife biologists ignoring those ideas. True, some of the ideas were put forth by people who had only observed captive wolves; their explanations were intriguing and rational, but it was admittedly taking quite a leap to extrapolate from the behavior of captive animals to include those in the wild.

But, clearly, there was a body of evidence which seemed both rational and pertinent and which was being ignored: what people who lived in the Arctic among wolves, who had observed them for years in the wild, thought about them. Second, there was an even larger issue: what could be inferred about the behavior of wolves from the lifeways of seminomadic human hunters who faced virtually the same problems as the wolf in securing game and surviving in the Arctic?

It is difficult, and perhaps ultimately pointless, to try to keep the two ideas separated. What the arctic hunter sees in the wolf. What we see of the wolf in the arctic hunter. The Nunamiut Eskimos, the Naskapi Indians of Labrador, the tribes of the northern plains and the North Pacific coast discussed below are all, in a sense, timeless. Even those tribes we can converse with today because they happen to live in our own age are timeless; the ideas that surface in conversation with them (even inside a helicopter at two thousand feet) are ancient ideas. For the vision that guides them is not the vision that guides Western man a thousand years removed from the Age of Charlemagne. And the life they lead, you notice, tagging along behind them as they hunt, really is replete with examples of the ways wolves might do things. Over thousands of years Eskimos and wolves have tended to develop the same kind of efficiency in the Arctic.

It is one of the oddities of our age that much of what Eskimos know about wolves—and speak about clearly in English, in twentieth-century terms—wildlife biologists are still intent on discovering. It was this fact that made me uneasy. Later, I was made even more uneasy by how much fuller the wolf was as a creature in the mind of the modern Eskimo.

If you examine what they have to say, if you watch Eskimos hunt, you discover something about wolves; but you also discover something about men and how they envision animals. For some, the animal is only an object to be quantified; it is limited, capable of being fully understood. For others, the animal is a likeness to be compared to other animals. In the end, it is unfathomable. The view from both places—the one slightly arrogant, the other perhaps more humble—gives you an animal neither can see. When you think about it, that’s quite extraordinary: a wolf that is both substance and shadow.

The hope of grasping that vision is grandiose. But that is what we are about.

In the spring of 1970, Robert Stephenson, a young wildlife biologist, went up to the small Eskimo village of Anaktuvuk in the central Brooks Range, some hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle. He was sent by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game to study wolf ecology in the region, to discover why the wolf population seemed to be in decline. He stayed for almost three years to study wolves with the Nunamiut people. He learned Inupiatun. He ate what the Eskimos ate. They liked him.

Stephenson had been studying arctic foxes; he knew very little about wolves when he arrived in Anaktuvuk, only some of what had been published by other wildlife biologists. It had not occurred to him then that most of their work had been done far to the south, and with only one subspecies of wolf, the Eastern timber wolf. And in a single, rather confined area: southern Ontario, adjacent northeastern Minnesota, and Isle Royale.

As Stephenson traveled around the tundra and mountain country of the Nunamiut, it dawned on him that the wolves he was watching were not like the wolves described in the literature he had read. And the Nunamiut were telling him things about wolves that no one, no biologist at least, had ever written about—not because they were odd or singular or mysterious things, but because they were things biologists were not interested in. Or never saw.

As Stephenson grew closer to the Nunamiut, as he gradually took on their sense of time and space (spending weeks during the full light of midsummer watching with powerful telescopes from foothill plateaus as wolves gamboled over sixty or seventy square miles of open tundra), his reflections on the animal led him toward a different understanding. Later, his wolf work would reflect an appreciation of the animal that was a blend of his academic knowledge and a primitive sensitivity that had been awakened, nurtured, and formed by his association with the Nunamiut. He had come among hunters to study a hunter, the one the Nunamiut called amaguk. Stephenson provided a bridge.

It can’t be emphasized too strongly that the wolf simply goes about his business; and men select only those (few) things the wolf does that interest them to pay attention to. The biologist counts placental scars on the uterus of a dead female, something that would never occur to an Eskimo to do. An Eskimo looking for caribou is attentive to the direction of movement of wolves in various places over a period of weeks, something the biologist might regard as only anecdotal information in his reports. The mistake that is made here, with consistency, it seems, only by educated Western people, is to think that there is an ultimate wolf reality to be divined, one that can only be unearthed with microscope and radio collar. Some wolf biologists are possessed of the idea of binding the wolf up in “statistically significant” data. They want no question about the wolf not to have an answer.

This is a difficult line to hew.

The Nunamiut Eskimos are genuinely pleased by the wolf biologist’s attempts to understand the animal because they, too, are very interested in the wolf. But they find the biologist’s methods sometimes unfathomable—and amusing. A Nunamiut man was once shown a radio collar. The electronic principle involved was outlined. It was explained that a wolf wearing such a collar could be tracked wherever he went—he could never hide. The Eskimo said, “That’s a very interesting piece of equipment. You should do that. You would learn a lot that way.” He was deferring to a system of inquiry different from his own; but he did not think the biologists would learn much more about wolf movements than Eskimos already knew.

Nicholas Gubser, an anthropologist, wrote of these particular Eskimos: “The more reflective Nunamiut do not search for a primordial cause, a complete explanation or order of the nature of ultimate destiny.” For the Nunamiut there is no “ultimate wolf reality.” The animal is observed as a part of the universe. Some things are known, other things are hidden. Some of the wolf is known, some is not. But it is not a thing to be anxious over. Their orientation is practical: the wolf’s pelt is valuable (especially to “crazy tannik,” the white tourist, who might pay $450 for one); watching the wolf, learning his ways, will make you a better hunter—not only a caribou hunter but a wolf hunter. A feeling of integrated well-being comes to the Nunamiut who knows so much about the wolf. Studying the wolf, he gets closer to the physical world in which he lives. The lack of separation from its elements distinguishes him from the biologist.

The Nunamiut have been watching wolves for as long as they can remember. Their knowledge is precise but open-ended. For a few weeks every summer, some of the Nunamiut men watch wolves with spotting scopes from campsites in the Brooks Range where they have an enormous field of view. One day Justus Mekiana, one of the older men, saw a wolf following a grizzly bear around all day, at a distance of about twenty yards. He took his eye from the spotting scope to say “That’s a new one, I haven’t seen that before.” Someone mentioned a family of wolves that had howled every day for two weeks during the denning season. Mekiana said he had never known wolves to do that, in forty years of watching them, but he added: “I wonder if wolves change their behavior over time, you know, different in some ways from thirty years ago?” If he is correct, then the implications for wildlife biology are staggering. It means that social animals evolve, that what you learn today may not apply tomorrow, that in striving to create a generalized static animal you have lost the real, dynamic animal. The nature of Mekiana’s stake in the right answer is such that he remains open to many more possibilities. This same man admired Rudolph Schenkel’s drawings and correctly identified the behavior associated with each, though he could not read a word of their English captions.

The thoroughness of the Nunamiut’s observation is the result of the keen attention given to small details, and, as is the case with all oral cultures, the constant exercise of a rich memory. On a riverbank, for example, faced with a few wolf tracks headed in a certain direction, perhaps a scent mark, the Nunamiut will call on his own knowledge of this area (as well as his knowledge of wolves, what time of year it is, and so on) and on things he has heard from others and make an educated guess at what this particular cluster of clues might mean—which wolves these might have been, where they were headed, why, how long ago, and so on. His guess will be largely correct. The Eskimo’s ability to do this, of course, astounds Western man.

Stephenson recalls one morning being out with Bob Ahgook, one of his Nunamiut friends, searching for a den. They were traversing a hillside when suddenly Ahgook stopped and pointed to a faint trail about four inches wide in some moss and lichen. By twisting his head to get the right angle of illumination and peering intently, Stephenson was able to make out a depression in the moss.

“Wolf trail,” said Ahgook, scanning the slope above them. Suddenly a white female, who had been sleeping 150 feet up the slope, stood up and stared at them, then turned, quickly ascended an escarpment, and disappeared. In the silence that followed a bird landed on a rock near where the wolf had been, moved around a few moments, then flew away.

“She has a den up there, see that?” said Ahgook.

“See what?” asked Stephenson.

“Where that robin landed, picked up some wolf hairs, and flew away? That would be a good sleeping place, maybe very close to a den.”

Stephenson recalled later that even though he had seen the bird it was so quick, so far away, he did not know it was a robin and would never have seen the wolf hairs in its beak. When they had climbed up to the spot it proved, indeed, to be a sleeping place. The female’s den was a hundred feet away. Ahgook said as the wolf departed that he saw she had shed hair around her mammae, which meant she was very close to giving birth.

As Stephenson himself demonstrated, the chances were excellent that all this would have escaped the field biologist. He would not have seen the track, looked up, or guessed at the den. Edward T. Hall, the anthropologist, has called this difference of sensitivity the result of a difference in “culturally patterned sensory screens.” And studies by Judith Kleinfeld have shown that Eskimos are very good at picking up visual detail, better than most whites.

Another thing that sets the Nunamiut and the biologist apart in the field is subtle, but worth noting. When the Nunamiut hunter goes out, he leaves his personal problems behind, as though they were a coat he had left on a hook. He slips, instead, into a state of concentrated, relentless attention to details: the depth of a track, the bend of grass along trails in a certain valley, the movement of ravens in the distance. It is the custom of most biologists, on the other hand, not only to bring their mental preoccupations into the field but to talk about them while they are walking along. Eskimos rarely speak when they are on the move and are inattentive to questions, giving only brief answers.

When the Nunamiut speaks, he speaks of exceptions to the rules, of the likelihood of something happening in a particular situation. He speaks more often of individual wolves than of the collective wolf, of “the white wolf that lives over near Chandler Lake,” or “that three-legged female who had pups last year.” He believes, too—and this seems quite foreign to the Western mind—that though equipped for it, the wolf is not a natural hunter. He must learn a good deal and work hard to become a good hunter.

One of the first practical things Stephenson noticed about the Nunamiuts’ knowledge of wolves was their ability to determine an animal’s sex and age at a distance by observing the condition and color of the pelage and fine differences in anatomy and behavior. (Some of these differences were mentioned in the first chapter.) Stephenson also learned that black wolves tend to be more high-strung than gray wolves; that two- and three-year-old females are the best caribou hunters; and that you might tell from a wolf’s track alone what color it was or whether it was rabid.

Such things take a long time to learn.

The Nunamiut make these observations on the basis of thousands of encounters and, like guesses about sex and age at a distance, they are based on many small pieces of interlocking detail. When a pack of wolves lies down to sleep on a hillside, it is the black ones, usually, that take the longest time to settle down. The black wolf, too, moves differently from the light-colored wolf when he crosses the tundra. It is a very subtle thing, but over the years it begins to fit and you come to believe, if you are a Nunamiut, that the black wolf is “a little more nervous.” In a caribou chase it is the sleek young females, built more like greyhounds than the males, that hunt caribou best because they are faster. As for telling a wolf’s color by its tracks, a very large track, one over 5½ inches long, is most often one left by a male black wolf. It just happens to be that way. And a rabid wolf has a tension in the muscles of his feet that keeps his footpads spread when he is walking on dry ground.

These are interesting things to know, especially entertaining to the Western mind, because there is a neatness to them we appreciate: they have a graspable, definable quality that would fit nicely in a handbook. When you spend time with the Nunamiut, however, it is not such encapsulated data that fascinates you so much after a while. The wolf the Eskimo sees is a variable creature who does things because he is a certain age, or because it is a warm day, or because he is hungry. Everything depends on so many other things. Amaguk may be a wolf with a family who hunts with more determination than a yearling wolf who has no family to feed. He may be an old wolf alone on the tundra, tossing a piece of caribou hide up in the air and running to catch it. He may be an ill-tempered wolf who always tries to kill trespassing wolves wandering in his territory. Or he may be a wolf who toys with a red-backed mouse in the morning and kills a moose in the afternoon.

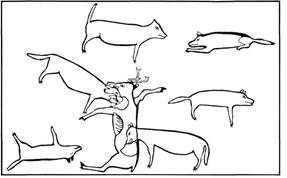

“Wolves Eating Caribou,” from a contemporary Eskimo print.

Examine some of the (until recently) basic precepts of wildlife science in the light of all this, such as that wolves kill primarily the weak, the old, and the injured. Too simple, say the Nunamiut. Temperature and humidity affect the wolf’s and caribou’s endurance. Terrain affects their ability to run. For caribou and moose, the nearness of deep, open water is important. With no water to get into, even the healthiest caribou may fall prey to the wolf, because no caribou can outlast the wolf. There are other things it is quite impossible to know, say the Nunamiut, but maybe the reason for some long chases is that some wolves like the taste of meat that has been run hard. Maybe, suggests one Nunamiut, healthy caribou are killed at times because when the wolves drive the caribou into an ambush, the healthy caribou get there first.

What about wolf territories? Depends on where the caribou are coming from, say the Nunamiut, the personalities in the pack, the season, whether there are pups, whether it’s a pack of males alone.

When a Nunamiut hunter goes out to kill wolves (there is no confusion in his mind between respect and reverence), all this that he knows about the animals comes to bear. He finds the wolf by watching the sky for ravens, because ravens are frequently looking for wolf kills and following them around. When he has located wolves, he hides somewhere downwind and opens the quiet arctic silence with a howl that carries for miles. (Best, the Nunamiut reminds you, to howl in the breeding season, on a cool day when the air is still.) He waits to hear if the wolf howls back. If he is going to come to you, the wolf comes right away. His sense of direction is so good he will almost always pass within your rifle range, even starting from three or four miles away. But if he hears the click of the rifle being cocked, he may disappear like fog.

When the Nunamiut is searching for wolf dens on the tundra, he doesn’t pay much attention to what yearling wolves in the vicinity are doing. He tells you yearlings are always fooling around. It is impossible to tell where a den may be by watching what they do. But older animals will show a pattern. Very subtle. Mostly it is how fast they are walking in what direction and at what time of day in June that tells you where the den might be. Subtle. Like the special way (to the Eskimo eye) the wolf holds his head when he smells caribou.

A correspondence begins to emerge.

The Nunamiut are a seminomadic hunting society, as are most of the Indian people I will consider in this section, who lead lives similar to wolves’. They eat almost the same foods—caribou, some sheep and moose, berries, not much vegetable matter. The harsh environment requires of them both the same stamina, alertness, cooperativeness, self-assurance, and, possibly, sense of humor to survive. They often hunt caribou in the same way, anticipating caribou movement patterns and waiting at likely spots to ambush them.

Hunting in this country is hard and Eskimos respect a good hunter. In all the time he spent with them, Stephenson never heard Nunamiut say anything degrading or contemptuous about a wolf. They admire his skill as a hunter because they know how hard it is to secure game. In the collective years of tribal memory there are very few stories about wolves that starved to death. The Nunamiut, on the other hand, have starved to death. Some of them alive today have gone for a month or more on only scraps of dried meat, pieces of caribou hide, and water. It is neither a mystery, nor surprising to anyone but a white man who no longer hunts for his food, that the Nunamiut admire the wolf and emulate his ways. In the land they share, hunting among the same caribou herds, hunting as the wolf does has proved to be the most reliable way to put meat in your belly.

I would like to suggest that there is a correspondence between the worlds of these two hunters about which the reader should be both open-minded and critical. I will not try to prove that primitive hunting societies were socially or psychologically organized like wolves that lived in the same environment, though this may be close to the truth. What I am saying is this: we do not know very much at all about animals. We cannot understand them except in terms of our own needs and experiences. And to approach them solely in terms of the Western imagination is, really, to deny the animal. It behooves us to visit with a people with whom we share a planet and an interest in wolves but who themselves come from a different time-space and who, so far as we know, are very much closer to the wolf than we will ever be.

What, if anything, does this correspondence mean? I think it can mean almost everything if you are trying to fathom wolves.

It became clear to me one evening in a single question.

An old Nunamiut man was asked who, at the end of his life, knew more about the mountains and foothills of the Brooks Range near Anaktuvuk, an old man or an old wolf? Where and when to hunt, how to survive a blizzard or a year when the caribou didn’t come? After, a pause the man said, “The same. They know the same.” The remark has special meaning for what it implies about wolves. It comes from a man who has had to negotiate in polar darkness and in whiteouts, when the world surrounding him was entirely without the one thing indispensable to a Western navigator—an edge. Anthropologist Edmund Carpenter has written of the extraordinary ability of polar Eskimos like the Aivilik to find their way about in a world that is often without horizon or actual points or objects for reference. What the Aivilik perceive is relationships, clusters of information that include what type of snow is underfoot, the direction and sound (against a parka ruff) of wind, any smells in the air, the contour of the landscape, the movement of animals, and so on. By constantly processing this information, the Aivilik knows where he is and where he is going. By implication, the Eskimo suggests that the wolf does something similar.

James Gibson, in a book called The Perception of the Visual World, wrote of not just one but thirteen kinds of depth perception. Most of us remain oblivious to such distinctions. We don’t need them. The Eskimo does; if he is not aware of such things, he will not find his way home.

What Gibson and Carpenter together suggest is this: he who reads the landscape without the aid of maps as a matter of habit becomes as sophisticated of eye as it is popular to believe the bat is sophisticated of ear. The Eskimo, in other words, probably sees in a way that is more analogous to the way the wolf sees than Western man’s way of seeing is.

If you are trying to fathom wolves, it is important to know how they might see. Maybe they see like Eskimos. And we can converse with Eskimos.

Recall the question asked of the old man. Who, at the end, knows more about the land—an old man or an old wolf?

Amaguk is like Nunamiut. He doesn’t hunt when the weather is bad. He likes to play. He works hard to get food for his family. His hair starts to get white when he is old. Young wolves, just like Nunamiut, run around in shallow melt ponds scaring the ducks.

And Amaguk is tough, living at fifty below zero, through blizzards, for months without caribou. Like Nunamiut. Maybe tougher. And Amaguk is smart. He sets up ambushes for caribou. He sleeps high up on the ridges when there are humans around. He brings his pups to a kill but won’t let them stay there alone. Grizzly bears. Young wolves do a lot of foolish things. Get killed.

Amaguk used to kill Nunamiut sometimes. Now Nunamiut can reach out and kill Amaguk from a distance with a rifle. Now Amaguk leaves Nunamiut alone.

Times change.

Amaguk and Nunamiut like caribou meat, know the good places for caribou hunting. Where ground squirrels are good. Where to get raspberries. A good place for getting away from mosquitoes. Where lupine blooms first in May. Where that big rock is that looks like achlack, the grizzly bear. Where the creeks are still running in August …

After a pause the old man looks up and says, “The same.”

What aligns wolf and primitive hunter more strongly than anything else is that to live each must hunt and kill animals. In an area where both men and wolves hunt, they tend to hunt the same sorts of game. Given the same terrain, weather, food storage problems, and the fact that they are hunting the same prey, they tend to hunt in similar ways. The differences between them have more to do with the fact that one moves around on two feet and kills with such extensions of himself as bullets and arrows.

The Naskapi, a seminomadic hunting people of northeastern Canada, live out a hard life in a bleak and almost barren landscape. For centuries they have hunted the same caribou herds the wolves have. I would like to turn to them now to illustrate some deeper ways in which wolf and human hunters are alike.

Here is the anthropologist Georg Henriksen writing about Naskapi hunters:

“On snowshoes, the hunters quickly shuffle away from camp carrying their rifles over their shoulders. The Naskapi walk at a fast and steady pace, keeping up the same speed hour after hour. When from a hilltop the men spot caribou some miles in the distance they set off at a brisk pace alternating between putting on their snowshoes when moving in deep snow, and removing them and hanging them over their rifle barrels as soon as they reach a hard and icy surface. No words are spoken. Half running, every man takes the wind, weather and every feature of the terrain into account and relates it to the position of the caribou. Suddenly one of the men stops and crouches, whistling low to the other men. He has seen the herd. Without a word the men scatter in different directions. No strategy is verbalized, but each man has made up his mind about the way in which the herd can best be tackled. Seeing the other men choose their directions, he acts accordingly.”

Approach, observation, conservation of energy, and attack—it could not be more wolflike.

It is said of the wolf that he is a deliberate hunter, that he does not wander aimlessly around the landscape but knows pretty well where prey animals are, even when he can’t see them. John Kelsall, a Canadian wildlife biologist, has seen wolves shortcutting cross-country in the taiga to intercept caribou two days ahead of them with almost pinpoint accuracy.

Again, Henriksen says of the Naskapi:

“The hunting grounds of the Naskapi do not teem with caribou. The Naskapi have to search for the animals, moving their camps and hunting over a wide range of country. In this search, they use their knowledge of the country and experience with the animals and their behavior under different circumstances. They take into account features of the terrain such as how hilly it is and whether it is forested or barren. They must consider the snow and ice conditions and relate them to the feeding and moving patterns of the caribou. They have theories about how other animals and insects such as wolves and warble flies affect the behavior of caribou. For example, when no caribou are found in an area where it was reckoned there would be plenty, they explain this by the presence of wolves. They said the caribou probably fled into the forest where the deep snow would keep the wolves at a distance.

“They make use of this knowledge and do not decide randomly where to search for caribou.”

It does not require two men, any more than it takes two wolves, to kill one caribou, but the Naskapi are social hunters anyway. Even when they hunt alone they are social hunters, because whatever meat they get is shared. The social fabric of the Naskapi tribe is the result of an acknowledgment of dependence on each other for food. The young, the old, the sick, they cannot hunt. The social system of the Naskapi bestows prestige on the successful hunter; that is what is exchanged for meat. Each man hunts as he chooses, calling on personal skills, but with a single, overriding goal: to secure food. The individual ego is therefore both nurtured and submerged. A man’s skills are praised, his food is eaten, his pride is reinforced.

I think a similar sense of social pressure and interdependence operates to hold a wolf pack together. Old wolves and young pups can eat only because the middle-aged wolves are good hunters. During rendezvous season the wolf, hungry himself, having eaten at the kill, returns home from ten miles away with a haunch of meat in his mouth. And he is besieged with as much affection as the successful Naskapi hunter is by his family. In this, perhaps more than anything else, we find a basis for alpha wolves—the hunters, whose prowess is encouraged for the sake of survival. Pack survival.

We now embark on a plainly metaphysical consideration.

The focal point of the act of hunting among the Naskapi is the preparation of a ritual meal, called Mokoshan. Caribou meat and bones are carefully prepared and consumed by the hunters. Not a morsel of meat or a sliver of bone may touch the ground. The function of the meal for the Naskapi hunter is to ingratiate himself with the Spirit of the Caribou, to indicate respect for his food, to honor the tenuous balance that keeps him alive by asserting that there will be no waste of whatever meat is secured in the hunt.

It is not hard for Western minds to miss the seriousness of this ritual: the link between hunter and hunted (symbolized in the meal) lies at the very foundation of every hunting society. It is, literally, the most important thing in the hunter’s life. To fail in the hunt is to fail to eat. To die. To be finished. The ritual preparation for the hunt, therefore, acknowledges a perpetual agreement: the game will be given to the hunter by dwellers in the spirit world as long as the hunter remains worthy. The hunt itself is but an acting out of the agreement, the bullet or arrow loosed but a symbol of the communication between hunter and hunted.

The agreement is mythic in origin, made with an Owner of the Animals. In the Naskapi world this is the Animal Master of the caribou because the caribou is the mainstay of the Naskapi diet. The Animal Master is a single animal in a great mythic herd. He is both timeless and indestructible, an archetype of the species. It is he who “gives” the hunter the animal to be killed and who has the power to keep the animals away from the hunter if he is unworthy. In the foundation myths of every hunting culture there is a story of how all this came about.

One time the people had no food—only berries and roots, no meat. A shaman steps forth and says he will go and find the food to make them strong. After a long and difficult journey he himself is on the verge of despair when he encounters the Owner of the Animals. The Animal Master challenges the man to show his power. He does, by bringing back to life a human being the Animal Master has struck dead. The Animal Master honors the feat by saying he will release the animals to be hunted, but under the following conditions: the hunters must treat the animals with respect, seeing that their flesh is not wasted and that their spirits are not insulted by acts of arrogance or ridicule; and the hunter must regularly perform a ceremony to commemorate this agreement. If this is done, the animals’ spirits will return safely to the Animal Master and he will give them new bodies and send them out again and again. In this way there will always be enough food.

Regurgitation. In cooperative hunting families, both human and wolf, hunters bring food back for those who do not hunt.

Hunting is holy. It is not viewed in the same light as an activity like berry picking. Game animals are holy. And the life of a hunting people is regarded as a sacred way of living because it grows out of this powerful, fundamental covenant.

THE SEA WOLF

One time a man found two young wolf pups on the beach. He took them home and raised them and one day after they were grown the man saw them go out into the ocean and kill a whale. They brought the whale back to shore so the man could eat. Every day it went like this. The wolves would go out and kill whales and bring back the meat. Soon there so much meat lying around on the beach it was going bad. When the Great Above Person saw this he made a storm and brought down a fog and the wolves could not find any whales to kill. The waves were so high the wolves could not even find their way back. They had to stay out there. Those wolves became sea wolves. Whale hunters.

—A story among the Haida of British Columbia

The killing of animals, then, entails tremendous spiritual responsibility. In the case of the Naskapi, as Frank Speck writes: “Failure in the chase, the disappearance of game from the hunter’s districts, with ensuing famine, starvation, weakness, sickness and death, all are attributable to the hunter’s ignorance of some hidden principles of behavior toward the animals, or his willful disregard of them. The former is ignorance. The latter is sin. The two together constitute the educational sphere of the Montagnais-Naskapi.”

Two more ideas are necessary here to complete our vision of the hunter and his food: that of the strength you gained from eating sacred meat (as distinct from what was gained spiritually and physically—virtually nothing—from other meat); and that of spirit houses as dwelling places for the spirits of the game animals, where you sometimes had to go in appeal during famine.

Hunting tribes called meat “medicine.” The word has two meanings. One is that meat is sacred because it comes from a sacred ceremony. The other is more literal in meaning and indicates why some native Americans did not care to eat, for example, the flesh of wolves. Hunting tribes understood the vegetable world as a pharmacopoeia; to some extent each tribe tried to cure its ills and ailments with herbs and plants. By taking the plant indirectly, concentrated in the form of meat from herbivorous animals, the hunter also indirectly partook of the plant’s power to cure and soothe. One of the reasons most native Americans avoided eating wolf meat was that it was the meat of a meat eater, not a plant eater. It was still meat—you could survive on it—but it was inadequate as food. Even worse than eating wolf meat was to eat meat from a domestic herbivore, like a cow. Cattle had no Animal Master. It was not sacred to hunt them, and on that food you could perish. (This, of course, was not a consideration until the coming of the white man.)

When a sacred animal was killed, its spirit went to a spirit house. For the Naskapi this was Caribou House. Caribou House was a real place. It lay in a mountain range west of Ungava Bay in present-day Quebec. The mountains there were white, not from ice or snow but from centuries of caribou hair falling on the ground. The caribou entered and left this place each year, passing through a valley between two high mountains. The caribou hair on the ground was several feet deep and for miles around the cast-off caribou antlers formed a layer as high as a man’s waist. The caribou paths were worn so deep a calf going along one would only show his head.

The Animal Master lived at Caribou House, together with the living caribou and the spirits of slain caribou. Animals in the surrounding area were fierce, larger than their normal counterparts, and much feared by the Naskapi. Yet in time of famine a tribe either had to conduct a ceremony of propitiation or someone had to go into this fearful land and deal directly with the Animal Master for release of the game.

That, briefly, is what hunting large game was for men. How does this touch on wolves? Can hunting be regarded as a sacred occupation among wolves? Is there a mythic contract acknowledged when wolf meets prey? Do wolves have a sense of Caribou House to which they raise mournful howls in times of famine?

We know painfully little about wolves. We can only ask the questions and guess. Communal hunting probably is the social activity that makes wolves hold together in packs. Sacred is not the right word, but hunting may have overtones for wolves that we cannot appreciate. We seem to sense them, though, when we speculate on the reasons for group howls after a successful hunt. I do not know if wolves have a sense of Caribou House. They do howl in time of anguish. The existence of Caribou House implies a rule of conservation and, in general, wolves are not wasters of meat.

We don’t know. But I am reluctant to let the idea pass unexamined. The wolf is a hunter. There is order to his world. It is not necessary that either wolf or his prey be conscious of this; a cursory examination of human hunting societies suggests that formal relationships between hunter and hunted are part of the order of the universe. It is reasonable to assume that some of these elements exist, even if they are unconscious or appear in another guise.

In the preceding section on hunting I merely touched on that moment of eye contact between wolf and prey, a moment which seemed to be visibly decisive. Here are hunting wolves doing many inexplicable things (to the human eye). They start to chase an animal and then turn and walk away. They glance at a set of moose tracks only a minute old, sniff, and go on, ignoring them. They walk on the perimeter of caribou herds seemingly giving warning of their intent to kill. And the prey signals back. The moose trots toward them and the wolves leave. The pronghorn throws up his white rump as a sign to follow. A wounded cow stands up to be seen. And the prey behave strangely. Caribou rarely use their antlers against the wolf. An ailing moose, who, as far as we know, could send wolves on their way simply by standing his ground, does what is most likely to draw an attack, what he is least capable of carrying off: he runs.

I called this exchange in which the animals appear to lock eyes and make a decision the conversation of death. It is a ceremonial exchange, the flesh of the hunted in exchange for respect for its spirit. In this way both animals, not the predator alone, choose for the encounter to end in death. There is, at least, a sacred order in this. There is nobility. And it is something that happens only between the wolf and his major prey species. It produces, for the wolf, sacred meat.

Imagine a cow in the place of the moose or white-tailed deer. The conversation of death falters noticeably with domestic stock. They have had the conversation of death bred out of them; they do not know how to encounter wolves. A horse, for example—a large animal as capable as a moose of cracking a wolf’s ribs or splitting its head open with a kick—will usually panic and run.

What happens when a wolf wanders into a flock of sheep and kills twenty or thirty of them in apparent compulsion is perhaps not so much slaughter as a failure on the part of the sheep to communicate anything at all—resistance, mutual respect, appropriateness—to the wolf. The wolf has initiated a sacred ritual and met with ignorance.

This brings us to a second point. We are dealing with a different kind of death from the one men know. When the wolf “asks” for the life of another animal he is responding to something in that animal that says, “My life is strong. It is worth asking for.” A moose may be biologically constrained to die because he is old or injured, but the choice is there. The death is not tragic. It has dignity.

Consider the Indian again. Native American cultures in general stressed that there was nothing wrong with dying, one should only strive to die well, that is consciously choose to die even if it is inevitable. The greatest glory accrued to a warrior who acted with this kind of self-control in the very teeth of death. The ability to see death as less than tragic was rooted in a different perception of ego: a person was simultaneously indispensable and dispensable (in an appropriate way) in the world. In the conversation of death is the striving for a death that is appropriate. I have lived a full life, says the prey. I am ready to die. I am willing to die because clearly I will be dying so that the others in this small herd will go on living. I am ready to die because my leg is broken or my lungs are impacted and my time is finished.

The death is mutually agreeable. The meat it produces has power, as though consecrated. (That is a good word. It strikes us as strange only because it is out of its normal context.)

I have been struck, considering these things, by the difference between captive and wild wolves, and I think that much of the difference—a difference of bearing, a dynamic tension immediately apparent in a wild wolf and lacking almost entirely in captive animals—lies in their food. The wolf in the wild subsists on his earned meat. The captive is fed on the wastes of commercial slaughterhouses and food made in factories by machines. Wolves in zoos waste away. The Naskapi, to this day, believe that the destruction of their people, the rending of their spirit, has had mainly to do with their being forced to eat the meat of domestic animals.

Plains Indians approaching buffalo.

The difference between wild meat and tame meat to a hunting culture is a matter of monumental significance. It was a fundamental principle of life that, in the case of the Indian, the white man simply never noticed and the Indians did not know how to explain. I remember the first time I gave a penned wolf a piece of chicken. And I remember the feeling in a Minnesota clearing the first time I came on a wolf kill, picked up the moose skull, and turned it in my hands.

Whether wolf and prey act according to some mutual understanding, or whether they only unconsciously participate in a fundamental drama, is something we shall probably never know. All we do know, staring up at the paintings of game animals on the cave walls at Lascaux, is that the belief that there was more to hunting than killing, and that dying was as sacred as living, was not something that one day just fell out of the sky.

This is a good place to pause and look back, because, as I said at the beginning of the chapter, the two ideas I began with—that modern hunting cultures can tell us much about wolves from their own observations, and that by examining these and older cultures and suggesting analogies with wolf behavior we can make engaging speculation—these ideas can run together.

We are basically finished at this point with the first idea, fleshing out the wolf modern biology has created by adding some observations made by Nunamiut hunters. As for the second idea, I have tried to make the point that hunting is a sacred activity among hunting peoples, the very basis of their social organization, and that it is not out of line to suggest the same for wolves. We should not be afraid—although we are, and profoundly so—to extend to the wolf and to the animals it preys on the physical and metaphysical variables we allow ourselves. It is, after all, not man but the universe that is subtle.

From here on, I will try to do two things. First, to suggest other analogies, other ways in which Eskimos and Indians led lives like wolves, in the hope that as you read them you will wonder as I do at the possibilities for the animal. And second, I will try to create a feeling for wolves that we may once have had as a people ourselves but have long since lost—one in which we do not know all the answers, but are not anxious. An appreciation of wolves, it seems to me, lies in the wider awareness that comes when answers to some questions are for the moment simply suspended.