THE INDIAN DID NOT think of the wolf as a warrior in the same sense as he thought of himself as a warrior, but he respected the wolf’s stamina and stoicism and he encouraged these qualities in himself and others. The wolf, therefore, was incorporated into the ceremonies and symbology of war. It was common practice for warriors to tie a wolf tail around the lower leg or ankle or at the back of a moccasin to signify an accomplishment in battle. Among the Mandan the practice was rather refined. A man who had never counted coup (to strike an enemy with one’s hand or a stick) was entitled to wear one wolf tail on his moccasin if he was the first to count coup in a fight; two wolf tails if he counted coup twice before anyone else did; and a wolf tail with the tip disfigured if he counted coup after someone else had in the same fight.

Assiniboin warriors wore white wolfskin caps smeared with red paint into battle.

The Wolf Soldier band of the Cheyenne was one of the best known of all the wolf warrior societies on the plains and it incorporated the most wolf lore.

The Wolf Soldiers were established early in the nineteenth century by a northern Cheyenne named Owl Friend. At that time, the northern and southern bands of the Cheyenne were traveling slowly toward each other. Owl Friend set out on his own one morning to reach the southern band. He wore a red robe and deer skin leggings with a great deal of porcupine quill and beadwork in them—very dressy, but he expected clear weather. In the afternoon a thunderstorm came up which changed to sleet and, later, to snow. By dusk Owl Friend suspected he was lost. He was also distraught over his ruined clothes. But thinking he must be near the southern Cheyenne camp, he pushed on. Finally, late that night, it seemed he came to a large tipi at the edge of a creek, which he took to be the Cheyenne camp. He went up and stamped the snow off his feet and a young man came to the door and welcomed him in.

There were four or five men in the lodge and he joked with them about almost getting lost in the snowstorm. His friends put him to bed to rest, while they warmed food and went about drying and softening his clothes.

Occasionally someone would come into the lodge and say something like, “Oh, our friend is here. It’s lucky he got in, he might have frozen in the storm.”

Owl Friend stayed in the lodge four days, waiting out the storm. He noticed a number of unusual things, among them four pipes, four lances with red shafts and scalps tied to them, and four drums. There were also rattles decorated with feathers and weasel tails.

On the fourth day the young men asked him to look around carefully at the things in the lodge. In addition to what he had already seen, Owl Friend noticed two hawk skins, two otter skins, two swift fox skins, a bear hide, and a wolf hide. The wolf hide was slit to fit over the head and eagle feathers were tied to the middle of its back.

On the evening of the fourth day the young men began to put on some of these things and to arrange the lodge for a ceremony. One of the young men went out to ask an old man to call in the Wolf Soldiers.

WARRIOR SONGS

The songs men sang while they traveled—short songs of encouragement or songs about a lover or in praise of past deeds—were collectively called wolf traveling songs by the Cheyenne. Such songs often came to warriors in their dreams. Francis Densmore collected this one among the Sioux:

A wolf

I considered myself

But the owls are hooting

and the night

I fear.

A warrior might also call on wolves in song to come and eat the flesh of his enemies after a battle, or, by comparing himself to a wolf, warn young men of the dangers that faced them, as in the following:

At daybreak I roam

ready to tear up the world

I roam

At daybreak I roam

shivers coming up my spine

I roam

At daybreak I roam

eyes in the back of my head

I roam.

—Santee Sioux song sung by Weasel Bear. Translated by JIM HEYNEN

Another man came over to Owl Friend. “You see us, the way we are dressing and preparing things?” he said. “This is the way you will do it.”

As people came in, Owl Friend could see the storm was still blowing hard, piling the snow deep.

A man named Wears His Robe Hair Out and three others began singing. The four lances were stuck in the ground. The four pipes were filled. The drums were smoked in sweet grass and one of the men struck the drum four times.

“Owl Friend,” he said. “Watch closely. You will have to imitate us. Remember the songs.”

Then the man looked up and said, “It will stop storming now,” and began the ceremony. The dancing and singing went on all night. Between songs they would smoke the pipes and someone would go outside to see the storm. “It is clearing off nicely,” they would say when they came back in. “You can see stars shining.”

Music recorded for a wordless Blackfeet wolf song.

They danced late into the night. Owl Friend watched how everything was done. When the dancing was over, they had a feast and the men put their clothes away. “Now we give it all to you,” they said to Owl Friend, and told him to go to bed. But before he did so he stepped outside. The sky was absolutely clear and most of the snow had melted.

When he awoke next morning before sunrise Owl Friend was surprised to find himself out on the prairie. He was surrounded by wolves, whom he recognized, howling in the dim light, as the young men he had stayed with. “Do this dance for four days and four nights,” they said. “When you are through, rub this medicine [balsam root, Balsamorrhiza sagittata] on your body. You will be Wolf Soldiers!”

With this the wolves left. Owl Friend returned to his camp with the dance and the other particulars of his dream to inaugurate the organization.

The Wolf Soldiers was the last of the seven great Cheyenne soldier bands to be formed. The origin story contains the common elements of camaraderie, elaborate ritual, and demonstration of power (over the storm). The function of these soldier bands was to defend the camp against attack and to act as police during buffalo hunts and on moves through enemy territory.

The Cheyenne Wolf Soldier ceremony was usually held in the late spring or early summer each year. It was both a ceremony of renewal for the members and an opportunity for young men to join. Members outfitted themselves as the wolf brothers had done in Owl Friend’s vision. Initiates wore only a breechcloth, and painted their hands and lower arms, feet and lower legs, and the lower portion of the face red, using crimson-colored earth or spring pussy willow buds.

At the conclusion of the ceremony each year a group of young Wolf Soldiers might elect to go raiding, as happened in the summer of 1819. Thirty Wolf Soldiers went north into Crow country, were surprised by a large Crow war party, and all killed. It was a tremendous blow to Cheyenne pride. The next year, the Wolf Soldier band having been all but wiped out, the other Cheyenne soldier bands—Dog Soldiers, Kit Fox Men, Red Shields—performed the ceremony of “Moving the Arrows Against the Crow” and attacked in revenge.

In the summer of 1837 a group of Wolf Soldiers (the society had by now gotten a name for being hot-blooded) whipped a medicine man named White Thunder until he agreed to perform the Cheyenne renewal ceremony of the Medicine Arrows early. He did so, telling them it wouldn’t work; but they took no heed. Forty-two of them went against a Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche encampment on the Washita River in west-central Oklahoma and, in a moment of panic, revealed themselves when they were on foot and without cover. All of them were killed.

The next spring a man who would later be called Yellow Wolf reorganized the Wolf Soldiers, renaming them the Bowstring Men, and set out to avenge the Cheyenne nation. They and their Arapaho allies struck a Kiowa and Apache camp on Wolf Creek in northwestern Oklahoma and met one of the most famous enemy warriors in Cheyenne history, a Kiowa named Sleeping Wolf.

The Cheyenne charged across Wolf Creek into the Kiowa camp. Sleeping Wolf grabbed a war club and led a countercharge on foot, driving the mounted Cheyenne back, but not without being leveled himself three times by warriors counting coup. Racing back across the stream, Sleeping Wolf grabbed a horse and again charged the Cheyenne. The horse was shot out from under him and while he fought on, again on foot and surrounded in the water, three more warriors counted coup on him. Managing to get away to the creek bank and to grab another horse, he got halfway across before the animal was shot out from under him and another bullet broke his leg. Three more times he was struck by warriors before finally being killed.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho were absolutely awed by this show of courage. Many of them, including all nine warriors who had struck Sleeping Wolf, would name their children for him. (The man was also known as Yellow Shirt for the buckskin shirt he wore that day, and Yellow Wolf is even today a common name among the Cheyenne.)

A few Cheyenne warriors named for wolves have put on extraordinary displays of power in battle. One of them was Wolf Belly, in a fight at Beecher’s Island, northeastern Colorado, on September 17, 1868. Fifty-three soldiers and civilian scouts were entrenched on the island in a dry riverbed, all of them armed with the new Spencer repeating rifle and the army’s new Colt revolver. The first Indian charge was shredded in a withering fire. The second charge, led by Wolf Belly, was also stopped, but Wolf Belly himself ran completely over the trenches and, jeering at the whites, crossed them again and again. The whites thought he was insane. Not a bullet struck him.

(In a curious aftermath to this battle, Capt. Louis Carpenter, patrolling some weeks later, came upon the burial scaffolds of nine of the Cheyenne killed at Beecher’s Island. He ordered his men to tear down the scaffolds so that wolves would desecrate the bodies. It was a common white belief at the time that the sole reason for elevating a body on a burial scaffold was to keep wolves from eating it. On the contrary, the Indians elevated the body out of respect. It was clearly understood that the gross body would be returned in this way to the earth from which it came, by the action of the rains and the winds, and by scavenging eagles, coyotes, and wolves.)

Another Cheyenne shaman, Wolf Man, was considered bulletproof after a fight on the Powder River in Wyoming in 1865 when, having been struck by two bullets, he simply shook them out of his vest.

WOLF MEN

Wolf Goes to Drink, Crow

Wolf’s Sleeve, Apache

Mad Wolf, Seminole

Wolf Calf, Blackfeet

Wolf Eyes, Hidatsa

Wolf Lying Down, Kiowa

Wolf Necklace, Palouse

High Wolf, Lakota

Yellow Wolf, Nez Perce

Many Wolves Waiting Near the Village, Tlingit

Wolf Walking Around a Person, Tlingit

Wolf Chaser, Crow

Wolf Bear, Crow

Wolf Orphan, Blackfeet

Wolf Robe, Acoma

Wolf Standing Alone, Kiowa

Wolf Face, Apache

The most honored warrior among the Cheyenne in the closing days of the plains wars was named Little Wolf. In September 1878, together with Dull Knife, he led 278 men, women, and children off the reservation in Oklahoma and north toward their ancestral home on the Yellowstone River in southern Montana. Their flight was arduous. Little Wolf distinguished himself in skirmish after skirmish but it all came to a tragic end, fighting in bitter cold without food or clothing that winter. The few left alive, including Little Wolf, were broken people.

The wolf name is still common among the Cheyenne: John Fire Wolf, Wolf Satchel, Blind Wolf are alive today.

Nothing has been said so far of women in connection with the wolf because where the wolf figured strongly, among shamans and warriors, there were few women. A woman’s involvement with wolves was more often a matter of her rolling up the sides of her buffalo hide tipi out of reach and putting her family’s belongings on a scaffold if they were going to be away for a while, to keep the wolves from getting into things. If a Cheyenne woman, for example, wanted to cure wolf hides, she had to protect herself against the consequence of touching such a powerful animal by undergoing a purification ceremony. A member of the Young Wolf Medicine Society painted her with red paint in the familiar way: the hands and feet, a circle on the chest representing the sun, and a crescent moon over the right shoulder blade, and lastly the face from the middle of the nose to the throat. A wolf hide resting on white sage (Audibertia polystachya) was similarly painted, but with a half moon on the right shoulder and a full circle on the back.

This ceremony was performed for a number of women at the same time. After snipping bits of hair from the wolf pelt, the women circled the camp—pausing at cardinal points to howl—and were then dusted by the master of ceremonies with white sage to signify removal of the paint, the end of the ceremony.

Women show up frequently in native American folklore and history as wives to wolves or their helpers. A Bella Coola woman who once helped a wolf with a difficult birth and helped still another wolf choking on a bone was widely known as a seer on the British Columbia coast, her shamanistic powers being a reward from the grateful wolves. Among the most moving of all these stories is one from the Sioux, about Woman Who Lived with Wolves.

The woman’s husband had treated her very badly and one evening, during a storm, she left, determined never to return. She traveled all night while the snow fell and covered her tracks. When the snow stopped falling, she started to leave a trail, so she climbed up to a ridge swept clear of snow and went on. She did not want her husband or her relatives ever to find her. She burned with a deep anger.

Walking down the ridge, she came to a cave which she entered to rest. She wrapped her robe around her and went to sleep. Sometime later she felt a slight movement. Opening her eyes, she saw dark forms poised over her. They slowly began to pull the wet robe away from her. She could tell now that they were wolves. As she lay there frozen in terror, the wolves curled up next to her and she felt their warmth. She turned her head very slowly until she was looking one of them in the face. He was asleep.

That evening the wolves left to hunt, returning in the morning with deer meat for her. She was so hungry she ate the meat raw. That evening she went out on the ridge to watch the winter sky, feeling her pain and anger. The wolves sat with her; they did not say anything. When she felt the pain the most, one of the wolves walked over and stood next to her.

She lived with the wolves for a long time, making her clothes from the deer hides they brought her and sharing their food, though she cooked her meat now, in a hole where the fire would not be seen. In time she learned how the wolves spoke and was able to talk with them. They told her about the places they had been.

One afternoon when they were all asleep in the sun, she realized it was time to go. Just as this thought came into her mind, one of the wolves opened his eyes and was looking at her.

Woman Who Lived with Wolves did not want to go back to her village, even though she was now a medicine woman. Instead, she went out on the prairie to live.

One day some young Sioux men were chasing horses when they saw Woman Who Lived with Wolves running in among them. She had accidentally been swept up in their drive, and though she could keep up with the horses, she knew she could not break away without being roped.

After many miles the horses began to falter and the young men concentrated on running down the woman. They finally got some ropes on her so she couldn’t move. They recognized her as the woman who had run away and returned with her to the village.

Woman Who Lived with Wolves remained distant among her people. They were kind to her, her relatives especially. She did not see her husband and no one said anything about him.

In time, in response to their questions, she told them of the time she had spent with the wolves. A man named White Bull was contemptuous of her and wanted to test her power. He was a powerful medicine man but insecure. He made people uncomfortable. White Bull told Woman Who Lived with Wolves to stand apart from him, that they would “shoot” things at each other to see whose power was strongest. White Bull went first. He shot her with bumblebees and rolled-up balls of buffalo hair. Woman Who Lived with Wolves did not flinch. Finally he shot her with “one of those small worms that comes out of the head of the elk.” This staggered the woman, but she did not fall.

Then it was Woman Who Lived with Wolves’s turn. She shot White Bull with a grasshopper and it was finished.

Her people believed in her and gave her her wolf name.

Wolves were not always benevolent figures in myth and legend nor strictly models for a warrior’s admiration. Indians understood them in a wider context. Wolves, like grizzly bears, could, after all, kill Indians. Those who tended to fear the wolf the most were the woodland Indians, who encountered them suddenly, usually at close quarters. Those who commonly saw them out in the open, on the tundra, for example, where they could more easily appraise the wolves’ motives, were much less fearful. But even they kept their distance. The nether regions of many tribes’ spirit worlds were inhabited by wolves which, in this context, were enemies. Nuliayuk, a great female sea spirit of Canadian Eskimos, was guarded in her undersea house by wolves. And there were enormous mythic wolves that lived near the Naskapi’s Caribou House and whose attacks hunters risked if they dared draw near.

Rabies was a real reason to fear wolves, for there were few more horrible deaths. A Blackfeet man bitten by a rabid wolf was bound with ropes and rolled in a green buffalo hide. A fire was built on and around him and he was subjected to this intense heat until the hide began to burn. The disease was believed to leave in the man’s profuse sweat.

Other tribes, notably the Navajo, feared wolves as human witches in wolves’ clothing. The Navajo word for wolf, mai-coh, is a synonym for witch. There is a good deal of witchcraft among the Navajo and belief in werewolves provides explanations for otherwise inexplicable (to them) phenomena. Witchcraft and werewolves are (the belief is current) more on the minds of some Navajos than others, specifically the more insecure, those who have many bad dreams or who suffer from a sickness or misfortune all out of proportion to those around them. Such people might be viewed by other Navajos as suffering the attention of werewolves.

A Navajo witch becomes a werewolf by donning a wolfskin. If he means to kill someone, he travels to his hogan at night, climbs up on the roof, and tosses something through the smokehole to make the fire flare, revealing where people are sleeping. He then pushes down a poison on the end of a stick, which the victim inhales. (Dirt rolling off the roof at night is a sign that a werewolf is about.)

In addition to killing people, Navajo werewolves raided graveyards and mutilated bodies. By taking the finger of a dead male or the tongue of a dead female (corresponding to the penis and the clitoris, respectively) and placing it near a living person, the werewolf ensured the vengeance of the spirit against the person, the spirit assuming that the living person had stolen the finger.

Modern Navajos are cautious around dead people and graves, and reluctant to press for the identity of a suspected human-wolf for fear of retaliation. If one is to be killed, they feel it wise to spread the task among three or four people. Most suspected werewolves are men and highly aggressive.

As a protection against witchery, Navajos even today keep gall around the house or on their person, sometimes wolf gall.

No matter who it was, whenever wolves were close everyone was a little nervous. One of the things wolves did in Indian camps that must have caused an eerie tension was to wander among the horse herds at night, drifting about in their shadowy way, lying down to rest among the animals or perhaps chewing through a rawhide picket rope. And then moving on, rarely disturbing even the high-strung horses.

Sometimes someone would bring wolf pups into a camp—a few tribes raised them for their fur—but it rarely worked out. The camp dogs killed them or they ran away or a nervous neighbor turned them loose or spirited them off. If you wanted to play with wolf puppies, you were better off going to a den. The parents would usually back off and you could dig the pups out. When Cree youngsters did this, they would sometimes paint the pups red around the nose and the lower limbs before putting them back. In their childhood game the pups were wolf warriors, just like themselves.

Once in a great while someone brought an exceptional wolf pup home and things went differently. Such a wolf one time came among the Blackfeet.

One spring two Blackfeet, Red Eagle and Nitaina, were hunting near Milk River in Montana after a heavy rainstorm. All the rivers were high; out on an island in one of them they spotted two wolves pacing anxiously back and forth. “There must be a den out there,” said Nitaina. “Let’s go see if there are any pups.”

They had a difficult time getting the horses through the mud and water onto the island. The big wolves barked and howled at their approach and then left, swimming to the far shore. There was indeed a den. Six drowned puppies floated in its entrance and one sat there in miserable silence.

Nitaina reached down and took the pup. “I will take him back,” he said.

People in camp said it was no good to keep a wolf, but Nitaina insisted. The wolf stayed close to Nitaina’s lodge, afraid of the camp dogs and wanting nothing to do with people. Wherever Nitaina went the wolf came along, picking up his habits. When Nitaina chased horses, the wolf chased horses. When Nitaina shot a deer that did not fall, the wolf brought it down.

When he was ten months old the wolf got in a fight with the camp dogs. He wounded several of them and people began to complain about having the wolf around. Nitaina ignored them. When the wolf greeted Nitaina he put his paws on his shoulders and mouthed his head. The man named him Laugher.

Late one spring, when the grass was high, some of the men decided to go horse raiding against the Cheyenne. Nitaina wanted to take Laugher along but the leader said no, which was his right. Many of the men felt Laugher was a strange wolf and bad luck to have around.

So Nitaina and Red Eagle and Laugher went southeast on their own, through Crow country to steal Sioux horses.

This was the first time Red Eagle had really been with Laugher. He liked the animal very much. One day Laugher killed an antelope by himself and became so excited he ran back and forth between the dead antelope and Nitaina three or four times, urging Nitaina to come see what he had done. It was good. It meant they could eat without having to fire a shot, which would have revealed their presence.

They went on for days, on foot, at night, sharing the antelope meat, until they came to the west side of the Bear Paws. Then they began traveling high on the mountains during the day, crossing Middle Creek and going up into the Little Rockies. One afternoon as they were rounding a bare rock butte Laugher stopped them suddenly. He put his nose on a rock and sniffed, and the fur on his neck stood up a little.

“Either a war party or a bear has been through here,” said Nitaina.

The men could find no tracks and urged the wolf to go on. Laugher moved slowly, working his ears and looking back often at the men creeping low behind him. When they reached the top of the butte, the men raised their heads slowly to peer over. For a moment they saw nothing. Then, within shooting distance, they saw a thin pall of smoke hanging in dense timber. Laugher, exposed on the ridge, began to howl. “No! No!” whispered Nitaina. But Laugher continued until two men were drawn out of the shadows to look around. They were Crows. They watched Laugher for a while, then went back into the trees.

Red Eagle and Nitaina slipped off the slope and ran hard until they reached a patch of cottonwoods at the foot of the butte. They had intended to walk right down the front of the butte. It would have meant their lives if Laugher hadn’t sensed the Crows.

That evening two men from the Crow war party sat as lookouts on the same butte where Nitaina, Red Eagle, and Laugher had been until morning, when they were joined by about twenty others and they all left.

In another week Red Eagle and Nitaina came on a Sioux camp on Little River. Expecting raids, the Sioux kept their horses in close to the lodges at night but turned them out during the day. Waiting their chance, the two Blackfeet grabbed two good-looking horses one morning, threw war rope bridles around their jaws and, rounding up thirty or forty others, broke for home. The Sioux immediately gave chase but Red Eagle and Nitaina, by jumping from one horse to another, were able to keep fresh mounts under them and stay ahead. They rode without stopping the rest of the day, all night, and into the next day, pushing the horses ahead of them. Laugher was a great help, keeping the horses moving and together. Finally they took a short rest at sundown.

They kept moving like this, taking only short rests, until they came in two days to the mouth of the Milk River. They had not seen Sioux behind them after the second day and felt safe now taking a long sleep.

Red Eagle took the first watch but could not stay awake. When he awoke, it was with a jolt. Nitaina was yelling: “Mount! Mount! Look at what’s coming!”

A war party on foot broke out of the trees at a distance and began firing. In a panic the two Blackfeet jumped on their horses and rode out, with Laugher bunching the herd and pushing behind them. One horse was killed. They didn’t stop riding for two days, until they swam the horses across Milk River and north into their own camp.

Laugher, once again, had saved them. It was he who had seen the war party hiding in the trees in time to waken Nitaina.

The Blackfeet in camp came to feel differently about the wolf after hearing what he had done, but Laugher remained distant. In a medicine lodge ceremony where all the men told of the times they had counted coup, Nitaina stood up and spoke for Laugher, and the men sent up war cries and banged on their drums, very pleased at this.

Some of the older men asked Red Eagle and Nitaina to bring Laugher and go after horses with them now, but they said no. The two men preferred going alone. They went once more that summer against the Cheyenne and with Laugher’s help again got twelve good pinto horses.

That winter Laugher began to disappear for days at a time. Finally he went off for three or four weeks and when he returned he was not alone. He stood on a hill near the village and appeared to be urging another wolf with him to come the rest of the way into the village. When the wolf wouldn’t come, Laugher went alone to Nitaina’s lodge but he did not stay long. He seemed restless, kept standing in the door and, finally, with a glance back at Nitaina, he left.

Nitaina did not see him for almost a year. Then he was with a third wolf, traveling across a valley in the Sweet Grass Hills. Two of the wolves ran off when they saw Nitaina approaching. Laugher stood watching for a few more minutes, then he, too, trotted off.

The next spring Red Eagle suggested that they go look for another wolf pup, maybe they would get lucky and find one like Laugher. But Nitaina said no.

The spirit that kept a people together through time, even as individuals passed away, was one of the most deeply felt emotions in the native American soul. Every year in small and large ways the spirit of life, of tribal identity and solidarity, of the individual’s place in the tribe, was renewed. And the wolf played a role here too, in some of the Pueblo masked rituals like the Hopi Snake Dance, and in the Sun Dance ritual of the plains. I would like to close this chapter by looking at two of these ceremonials, one from the Nootka and the other from the Pawnee.

The wolf ritual of the lower Pacific northwest coast, among the Nootka, Kwakiutl, and Quillayute, was the major masked ritual in this part of the country. Usually held in the beginning of winter before a full moon, it was hosted by someone prominent in the village and served to welcome young people formally into the tribe. Tribal initiation in the wolf ceremony was central to one’s sense of identity with the tribe, and participation was necessary before one could take part in any other ceremony. It also renewed a sense of tribal identity for former initiates who participated.

Although the ceremony differed slightly among the various tribes and clans, lasting five days with some, nine days with others, it derived from the same myth and was performed in essentially the same way.

The mythic basis for the initiation ceremony (as distinct from healing and puberty ceremonies like the Whirling Wolf Dance or Crawling Wolf Dance) was the stealing of a young man by a pack of wolves. The wolves tried to kill him but could not and so they became his friends. They taught him about themselves, then sent him back to his village to teach his tribe the rites of the wolf ceremony. The young man told his people that it was necessary for the strength of the tribe, for their success in war, and everything else they did, that they should be like wolves. They must be as fierce, as brave, and as determined as the one who is the greatest hunter in the woods. In this ceremony people are “stolen” by wolves, go through a terrifying confrontation, and emerge wolflike.

Among the Makah, a division of the Nootka, the ceremony begins with the gathering in the evening of the older men in the tribe, dressed in cedar and hemlock branches and blowing on small wolf whistles made of bone. They gather the young initiates quietly from their homes and take them to the house where the ceremony, the Klukwalle, is to be performed. On the second day messengers go through the village specifically asking each person in the tribe to come that evening to Klukwalle.

Toward dusk the people begin to gather and the procession winds its way to the ceremonial house.

Inside, to the accompaniment of drums and bird rattles, each member of the tribe sings his tse-ka, or personal medicine song, around a central ceremonial fire. The evening builds with tse-ka singing until someone throws back his head and the first wolf howl is heard in the lodge. Soon everyone is howling and then the howls of real wolves, responding from the woods outside the lodge, begin to be heard, louder and louder. Outside, human wolves are banging on the walls; the children are terrified. Some of the participants have already put on wolf masks and have begun to act threateningly. They are restrained with cedar bark ropes until the evening grows tame, with a fading of the songs and a quieting of the wolves banging on the walls.

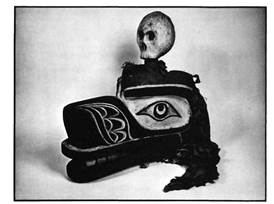

Wolf mask, Kwakiutl.

The third day begins with a ritual cutting of the flesh on the initiates’ arms. Among the Makah this might have been a reenactment of a gashing that their culture hero, Ha-sass, subjected himself to. (Ha-sass wished to learn the ways of the wolves but he was afraid that if they smelled his blood they would know he was human. He had his brothers cut him with shell knives until his blood was drained away before he went to the cave where the wolves lived.)

When the gashing is completed, the initiates go outside for the first time in a procession through the village, with their wounds dripping. After noon they either go to their own homes or back to the ceremonial lodge to rest for the evening performances.

After dark the tribal members again wind in a procession past all the homes to the ceremonial house. More masks are now evident, including the raccoon mask and the honeybee mask. The tse-ka songs are sung, the bird rattles and drums are heard, the wolf cries go up, and for the first time there is dancing. The people in the wolf masks become more and more agitated and try to put the fire out. Restrained by the cedar ropes the wolves go into the wolf frenzy to show their power, and the initiates, many of them terrified by the howling and dancing of the wolves, begin their own dances to demonstrate a willingness to be in touch with these spirits. The frenzy of the wolves builds until they finally succeed in stamping out all the fires.

After a period of darkness the fires (for warmth and light but with spiritual overtones) are rekindled and the people eat.

The fourth day of the ceremony marks its climax, when all the members of the tribe put on their personal masks reflecting individual identity—deer, woodpecker, eagle—and costumes and proceed to the lodge to take part in the larger tribal ceremony. Waiting inside are unmasked members of the tribe who, at the appointed time, unmask each person, symbolically returning him to his human form. The unmasking of those people who are wearing the wolf masks calms the wolf frenzy. In their sudden serenity is evidence of their rebirth; the strength of their bearing shows they have internalized the strength of the wolf.

By now the young initiates have decided which animal will be their personal animal and have fashioned a mask to a likeness. The evening ends with a feast and a breaking of their fast. On the morning of the fifth day they will go down on the beach and dance with their masks on for the first time.

The Makah Wolf Ritual represents a middle ground between the sort of rituals in which the children are stolen by tribal members in wolf masks, returned after a few days of mourning, and revived by tribal members, and the more bizarre rituals of northwest coast tribes to the north, where the spirit of the wolf is replaced by the spirit of the cannibal.

However it is played out, the wolf ritual represents a personal and tribal renewal in the context of those warrior qualities that the wolf was thought to possess and that would stand tribe and individual alike in good stead.

A different aspect of tribal identification with the wolf is seen among the Pawnee, whose climatic renewal ceremony came in the spring. Called the Captive Girl Ceremony or Morning Star Sacrifice, it involved the ritual death of a young, non-Pawnee woman who was stolen in a raid. In the cosmogony of the Pawnee, Morning and Evening Star had warred and Morning Star had won; from their union the first human being was born, a girl. From time to time Morning Star revealed himself in a dream to a Pawnee warrior, telling him he wanted a girl for himself in return for the one he had put on earth.

The symbolism of the ceremony is elaborate but its focus is on death and rebirth. Since the wolf was the first animal to experience death (in the Pawnee creation legend opposite), his symbolic presence is essential. He arrives in the person of the Pawnee Wolf Man, the keeper of the sacred “wolf bundle.” He takes care of the captive girl from just before the winter buffalo hunt when she is stolen until the sacrifice takes place in the spring. He treats her kindly, sees to her needs, and it is he, finally, who walks her to the sacrificial scaffolding.

The Pawnee were in some ways the most complex of the plains tribes because they were both an agricultural and a hunting people. The renewal of their corn crops and their annual buffalo hunts were two driving forces in their ceremonials and in all of them the life-death cycle—which functioned through the agreement with the Animal Master and the renewal cycle of the crops—was central. The wolf, that Red Star of Death in the southeastern sky, was associated with both corn and buffalo in the Pawnee mind; the birth and death of the Wolf Star (Sirius) each night as the earth turned was but a reflection of the wolf’s coming and going from the spirit world, down the path of the Milky Way, which they called the Wolf Road.

The wolf was a symbol of renewal, just as the willow, the sacred tree of the southeast, was a symbol of death and rebirth. When the willow was cut down it grew back quickly, just as the wolf who was the first to be killed became the first to return from the dead. At that time, in the heyday of the Pawnee, anyone could look out on the prairie and know these things were true. He could hear the songs of the wolf, like the songs that took up a man’s life from birth; he could see the wolf trotting, trotting, trotting, like a warrior, like people moving camp, in the great coming and going that was life.

THE PAWNEE CREATION LEGEND

It is told in the creation legend of the Pawnee that a great council was held to which all the animals were invited. For a reason no one remembers, the brightest star in the southern sky, the Wolf Star, was not invited. He watched from a distance, silent and angry, while everyone else decided how to make the earth. In the time after the great council the Wolf Star directed his resentment over this bad treatment at The Storm that Comes out of the West, who had been charged by the others with going around the earth, seeing to it that things went well. Storm carried a whirlwind bag with him as he traveled, inside of which were the first people. When he stopped to rest in the evening he would let people out and they would set up camp and hunt buffalo.

One time the Wolf Star sent a gray wolf down to follow Storm around. Storm fell asleep and the wolf stole his whirlwind bag, thinking there might be something good to eat inside. He ran far away with it. When he opened, it, all the people ran out. They set up camp but, suddenly, looking around, they saw there were no buffalo to hunt. When they realized it was a wolf and not Storm that had let them out of the bag they were very angry. They ran the wolf down and killed him.

When The Storm that Comes out of the West located the first people and saw what they had done he was very sad. He told them that by killing the wolf they had brought death into the world. That had not been the plan, but now it was this way.

The Storm that Comes out of the West told them to skin the wolf and make a sacred bundle with the pelt, enclosing in it the things that would always bring back the memory of what had happened. Thereafter, he told them, they would be known as the wolf people, the Skidi Pawnee.

The Wolf Star watched all this from the southern sky. The Pawnee call this star Fools the Wolves, because it rises just before the morning star and tricks the wolves into howling before first light. In this way the Wolf Star continues to remind people that when it came time to build the earth, he was forgotten.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century in preparation for the Hidatsa Sunrise Wolf Bundle Transfer Rite, an old man named Small Ankles lamented with his son that it was going to be hard to do the ceremony properly because it was hard to find a wolf around anymore. In the transfer rite the Hidatsa engaged in a kind of “historic breathing,” inhaling the past and emphasizing its place in the now, the present. To lose the ceremony would be to lose the past, to be undefined, nothing, broken. The time of the Indian, Small Ankles knew, was waning, as was the time of the wolf.

One morning in Montana I sat in the home of an old man named Raven Bear, a Crow. He had made a trip to Seattle a few years before to see his family. One day he took his grandson and drove to the Olympic peninsula where he had heard there was a commercial zoo with a number of wolves. He found the place, paid six dollars and went in. In a while he was ashamed he had brought his grandson there. The wolves were all in small pens, obese animals suffering from diseases, he thought. The people running the zoo told him the wolves were the last remnants of the Great Plains wolf, Canis lupus nubilis. “I wanted to tell the man he didn’t know what he was saying,” said Raven Bear, “but I didn’t know how to do that. I just took the boy and left.”

It was late at night. Raven Bear was sitting on the top of a bunk bed with his stocking feet hanging over the edge. After a while he said, “It hurts like hell, you know, to see it finished.”