MAN HAS ALWAYS SOUGHT to legitimize his hunting of wolves, even when it was at the ragged edges of decency. One of the defenses he offered was that it was simply “good sport” to hunt wolves—the wolf was taken for the admired enemy. Even though many of these men bore the wolf no overt hatred, their methods could not always be called sporting, however.

Theodore Roosevelt hunted wolves in Russia and North America with dogs, sometimes on a grand scale, and he made no apology for it. (He once set off with seventy fox hounds, sixty-seven greyhounds, sixty saddle and packhorses, and forty-four hunters, beaters, wranglers, and journalists, all in a private train of twenty-two cars.) In Russia there was a veneer of upper-class respectability to such hunts; in America there was rarely legitimate claim to sport in coursing, though that was often its guise. Roosevelt was quite clear on this point. Writing of an acquaintance who hunted wolves with dogs in North Dakota, he said: “The only two requisites were that the dogs be fast and fight gamely; and in consequence they formed as wicked a hard-biting crew as ever throttled a wolf. They were usually taken out ten at a time, and by their aid Massinggale killed over two hundred wolves, including pups. Of course there was no pretense of giving them fair play. The wolves were killed for vermin, not sport… .”

Wolf hunting in Europe and Russia with hounds was an aristocratic amusement, popular around the turn of the century. While nobility and its guests dined and relaxed in the hunting lodge, the head huntsman and his helpers scoured the countryside for wolf sign or learned from local peasants where the wolves were. On the day of the hunt the gentlemen arrayed themselves in a line at the edge of a promising wood and the head huntsman tried to howl up a wolf. If an answering howl was heard—“commingling the lament of a dying dog with the wailing of an Irish Banshee”—the dogs began driving the woods from the far side. A beater might have as many as six dogs on leashes as he moved through the woods. Deerhounds, staghounds, and Siberian wolfhounds, the slender white borzoi, as well as smaller greyhounds and foxhounds. When he saw a wolf, he would shout: “Loup! Loup! Loup!” and slip the dogs. The idea was to trap the wolf between pursuing dogs and the hunters sitting astride their horses at the edge of the wood. Bursting from cover, the wolf would either be shot or pinned by the dogs and then speared or clubbed. Sometimes the dogs, especially the larger mastiff crossbreeds and hounds, would kill the wolf.

Wolves were also coursed, or chased, by dogs and horsemen through open prairie country where they were worried by the hounds until lassoed or shot. George Armstrong Custer was a devotee of coursing and usually traveled with a retinue of dogs. He was partial to larger greyhounds and staghounds and took two of the latter, large, white, shaggy dogs, with him into the Sioux’s sacred Black Hills where he turned them loose on deer and wolves. The southern Cheyenne, who hated Custer, killed one of his favorite staghounds, Blucher, at the Battle of the Washita in Oklahoma in 1868.

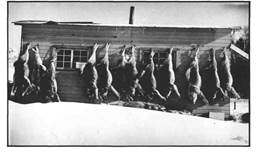

A wolfer with his hounds, near Atnmedon, North Dakota, 1904.

A popular kind of wolf hunting in the winter in Russia was done from a flat sled drawn by horses. A butchered calf or pig or a bale of bloody straw was trailed behind, or a live pig’s leg was twisted to make it squeal, until wolves fell in behind the sled. The wolves were then shot. Stories of sled hunting abound in Russia and the failure of this scheme—the horses tire or there are too many wolves or the wolves are too fast or the sled flips over in an icy turn—is a staple incident in Russian fiction. Commonly the hunters lose their driver and horses to the wolves and spend a harrowing night under the upturned sled, holding the wolves off in the manner of a wagon train surrounded by Indians until morning. The wolves drift off at first light, having killed their own wounded and eaten their own dead, and human help usually arrives in the person of distraught friends who feared the worst when the adventurers didn’t return.

The most exotic sort of wolf hunting involves the use of eagles. It has been seen only occasionally in Europe; its real home is Kirgizia, in south-central Russia. The specially bred birds—a subspecies of golden eagle called a berkut—are flown by nomadic tribesmen. The birds weigh only ten or twelve pounds but can slam into a wolf’s back and bind its spine with such force that the wolf is almost paralyzed. Often the bird binds the spine with one foot and, as the wolf turns its head to bite, binds its nose with the other foot, suffocating the animal or holding it down until the hunter kills it. The birds are deceptively strong; there is almost a ton of binding force in each foot and the blow of a thirty-six-inch wing can break a man’s arm.

Eagles probably never attack adult wolves in the wild; wolf hunting is something they have to be trained to. A former German military officer, F. W. Remmler, hunted wolves with eagles in Finland in the 1930s and later in Europe before moving to Canada. He trained his birds by first turning them loose on children. The children were dressed in leather armor and covered with a wolf skin, and raw meat was strapped to their backs. When the eagles were used to knocking the children down for the meat, Remmler put them in an enclosure into which he loosed wolves purchased from European zoos. It might take days for the birds to learn how to kill the wolves. (Remmler doesn’t say, but they were presumably muzzled.) The final step was to hunt wolves that had been turned loose on an island. Remmler and his friends would put themselves in position and the wolves would be driven toward them by dogs. When the wolves came in sight, the birds were cast off.

Writing thirty years later about one such hunt, Remmler recalled an afternoon when one of his eagles, Louhi, had killed two wolves in ten minutes. That night as Remmler and his friends sipped cognac around the fire they heard the howling of the other five wolves on the island. “First the female and then the pack stretched their noses toward the starlit heavens,” he wrote, “and both gave a howl so dreadful that my blood almost hardened in my veins. It may be that I had drunk too much that night, but the horror that filled me was very real. If I could have given the two dead wolves their lives back I would have done it immediately.”

Kirgizian tribesmen still hunt wolves in Russia with eagles, on horseback, with the aid of dogs.

Because he roamed so widely and more often than not avoided man, the wolf had to be routed out with dogs or eagles or drawn to a bait. Still hunting, where a sheep or goat was staked out, was never very successful, though a horse or cow might be slaughtered and its carcass dragged through the woods to leave a trail ending at a spot where the meat was hung in a tree and the hunter concealed himself. (Residents of rural northern Minnesota laughed up their sleeves when hunters from urban Minneapolis, threatening to wipe out wolves preying on deer herds in the early 1970s, bought steaks and lunch meat at local supermarkets, set it out on frozen lakes, and waited in blinds for the wolves to show up.)

The reasoning behind hunting wolves for sport as opposed to hunting them because they were hated or considered a menace to livestock was often confused. Consider the following hunt that took place near Tarnworth, New Hampshire, in 1830, described by Charles Beals in Passaconaway in the White Mountains.

“On the evening of Nov. 14 couriers rode furiously through Tarnworth and the surrounding towns, proclaiming that ‘countless numbers’ of wolves had come down from the Sandwich Range mountains and had established themselves in the woods on Marston Hill. All able-bodied males, from ten years old to eighty, were therefore summoned to report at Marston Hill by daylight on the following morning.

“Marston Hill was crowned by about twenty acres of woods, entirely surrounded by cleared land. Sentinels were posted around the hill and numerous fires were lighted to prevent the wolves from effecting a return to the mountains. All through the night a continuous and hideous howling was kept up by the besieged wolves and answering howls came from the slopes of the great mountains. The shivering besiegers were regaled with food and hot coffee furnished by the women of the country-side throughout their long lonely watch.

“All night long reinforcements kept arriving. By daylight there were six hundred men and boys on the scene, armed with rifles, shotguns, pitchforks and clubs. A council of war was held and a plan of campaign agreed upon. General Quimby, of Sandwich, a war-seasoned veteran, was made commander-in-chief. The general immediately detailed a thin line of sharpshooters to surround the hill, while the main body formed a strong line ten paces in the rear of the skirmishers. The sharpshooters then were commanded to advance towards the center, that is, towards the top of the hill. The firing began. The reports of the rifles and the unearthly howling of wolves made the welkin ring. The beleaguered animals, frenzied by the ring of flame and noise, and perhaps by wounds, made repeated attempts to break through ‘the thin red line,’ but all in vain. They were driven back into the woods, where they unceasingly continued running, making it difficult for the marksmen to hit them. In about an hour the order was given for the main line to advance, which was done.

“Closing in on the center, the circular battle-line at last massed itself in a solid body on the hilltop, where, for the first time in sixteen hours, the troops raised their voices above a whisper, bursting out into wild hurrahs of victory. Joseph Gilman records that few of the besieged wolves escaped. But the historian of Carroll County maintains that the greater part of the frantic animals broke through the line of battle and escaped to the mountains whence they had come. Returning to the great rock on which the commander-in-chief had established headquarters, the victorious warriors laid their trophies at the feet of their leader—four immense wolves—and once more gave thrice three thundering cheers.

“The little army then formed column, with the general, in a barouche, at its head. In the barouche also reposed the bodies of the slain wolves. After a rapid march of thirty-five minutes, the triumphant volunteers entered the village and formed a hollow square in front of the hotel, the general, mounted on the top of his barouche, being in the center of the square. What a cheering and waving of handkerchiefs by the ladies, in windows and on balconies, there was! General Quimby then made a speech befitting the occasion, after which the thirsty soldiers stampeded to the bar to assuage the awful thirst engendered by twenty mortal hours of abstinence and warfare.”

The paramilitary aspect, the mock nobility, and the odd air of gaiety were frequently the major themes of such hunts.

Saturday afternoon wolf killings were a popular social pastime in the Midwest at the turn of the century. Bounties collected on the dead wolves were pooled to pay for end-of-the-season parties. “In three ways,” wrote one participant, “does the most popular spring enjoyment of the prairie states—the wolf hunt—originate. The farmers may desire earnestly to rid the township of ‘varmints’; the men of the community may want a day of entertainment; an enterprising hardware dealer may wish to enliven the market for gunpowder and shotguns. With them all wolf hunts become increasingly numerous, not because wolves are more common, but because it is an occasion of healthful outdoor exercise and fun.” These farmers more often killed a coyote than a wolf during these outings. Their casual attitude toward the hundreds of rabbits, prairie dogs, burrowing owls, gophers, and other small game killed in the process, and their habit of hanging the wolf’s carcass from a pole and parading it through the streets on a Saturday night, was part of the barbarism of the times. There were few, if any, misgivings. A contemporary writer, O. W. Williams, comments: “If the lobo has any useful qualities or habits I have not yet learned of them. If it destroys any noxious animal, reptile or insect in appreciative quantity, I have no account of it. It seems to be a specialist in carnage and to have brought professional skill to the slaughter of cattle. Possibly it has its uses—but it will require a skillful man with a very high powered magnifying glass to ascertain them.”

Aerial hunting for wolves in the modern age is a difficult practice to understand. It seems unfair and cruel. Wolves caught out in the open on the arctic tundra or on a frozen lake are approached with highly maneuverable aircraft and blasted with automatic shotguns. The plane lands and the trophy hunter picks up his prize. In Alaska, where the practice was widespread before it was outlawed in 1972, it was not uncommon for two men in a plane to catch ten or fifteen animals—the whole pack—in the open with no cover and methodically kill every one of them. In their defense pilots claim it was difficult to shoot a moving target from a moving plane, that in such low-level, low-speed flying it is easy to stall the aircraft, that a bad shot could blow away a wing strut, and that winter flying—in intense cold with a possibility of whiteouts and crashing in unpopulated regions—was dangerous.

The pilots were right. Planes were shot up, apparently chances to kill were missed, and people were killed when wolves turned to snap at the plane’s skis and caused it to crash. But, overwhelmingly, it was a case of dead wolves, healthy hunters, and pilots exaggerating the dangers to lure still more clients—and coming to believe their own exaggerations when an outraged public tried to stop the practice. Adding to the shabbiness of the episode was the fact that the hunter-clients were usually rich, urban men who knew nothing about wolves and nothing about the Arctic. They commonly believed all wolves weighed two hundred pounds and that any movement a wounded wolf might make once they were on the ground was an attempt to attack them. The illusions were encouraged by the pilots, who took the pelt and left the carcass behind on the snow. Back in Kotzebue or Bettles or Fairbanks the story was embellished and hunter and pilot congratulated for their bravery and daring. It is both ludicrous and tragic that the death of a wolf so cheaply killed confers such enormous prestige.

There is something deep-seated in men that makes them want to “take on” the outdoors, as though it were something to be whipped, and to kill wolves because killing a wolf stands for real triumph. In view of the way most wolves are killed it is hard to see how the image is sustained, but it is. Hunting is an ingrained male activity, especially in rural America, where few male children grow up not wanting to hunt. I hunted as a boy and I remember very clearly the first time I thought there was something wrong with the men I admired, something fundamentally backward about the kind of hunting that was held out to me as what men were supposed to do in the course of things. I was reading a book about big game animals in which Jack O’Connor, then the gun editor of Outdoor Life, described suddenly coming on seven wolves on a river bar in the Yukon. O’Connor dismounted and opened fire. “With considerable expenditure of ammunition,” he wrote, he killed four of them, and then said he was sorry he’d done it for two reasons. “For one it was August and the hides were worthless. For another, my shooting spooked an enormous grizzly bear.”

I couldn’t get over that.

O’Connor writes elsewhere that the greatest satisfaction he had in killing a wolf came in British Columbia while he was sheep hunting. A wolf was doggedly pursuing a sheep up a steep slope. When the wolf stopped for a breath, O’Connor leveled his gun. “It was a lovely sight to see the crosshairs in the 4X settle right behind the wolf’s shoulder. Neither ram nor wolf had seen me. The wolf’s mouth was open, his tongue was hanging out, and he was panting heavily. The ram, on the other hand, seemed hardly bothered by the run. When my rifle went off, the 130 grain .270 bullet cracked that wolf right through the ribs and the animal was flattened as if by a giant hammer.”

Magazine illustration, 1964.

O’Connor spoke for a generation of men who matured in the twenties, thirties, and forties in America. He shot at every wolf he ever saw, including the only one he ever saw in the lower forty-eight states. For all he knew about guns and camping he seemed to know next to nothing about wolves, which was also typical of his generation of hunters. He never questioned his own role as a predator, nor his right to kill another predator, like the wolf, in pursuit of its game. It was largely these sorts of hunters, smug and ignorant, weaned on stories of vicious wolves, innocent deer, and poor, starving Eskimos, who became the most righteously vocal defenders of aerial hunting. As a result, at the height of the craze its appeal was to a sense of duty (protect the defenseless herds and help the starving Eskimo), to violence (permissible in defense of the defenseless), and to a distorted sense of manhood. Argument over whether it was a sport disappeared. One hunter, promoting the activity to a sympathetic audience, wrote ecstatically of “not being more than thirty feet above the animals, so close I saw the hair fly from one of the black wolves as the hail of buckshot hit it. The wolf went down, rolling and kicking, biting at its side. Confused, the other wolves crouched, looking up at us. Tom, an enthusiastic wolf-hunter, who had once shot a cylinder off his plane trying to kill a wolf from the air, pulled the plane up into a jubilant chandelle, then let it drop off in a screaming, side-slipping dive that brought us in behind the wolves again.”

This anecdote ends with embarrassing self-parody. “ ‘If I could afford it,’ said Tex with satisfaction as we landed to pick up the pelts, ‘I wouldn’t do nothin’ but fly around an’ hunt them varmints. Every time I kill one it makes me feel good.’ ”

When such “hunters” stood before national television cameras in sunglasses and flightsuits and pretended to eat raw the flesh of wolves they’d just killed, they only exposed their own foolishness and the mockery they had made of traditional hunting ethics.

The sport hunter and the roustabout do-gooder came together in an interesting character in Alaska in the 1930s. During the Depression, a number of men drifted north in hopes of making a living as trappers. Most didn’t. Some who did wrote about their experiences with wolves in magazines like The Alaska Sportsman. These men were mostly ignorant of the woods when they arrived; their stories are full of errors and cruelty to wolves and are punctuated by a righteous hatred for the animal. They believed wolves attacked and killed men in the north country, and they seemed barely able to control themselves when they told you what the wolves did to deer. “I knew what I’d find,” wrote one, “deer hair and crushed bones, rent tissues and blood,” as though wolves might have left something else. Stories with titles like “Wolves Killed Crist Colby,” “I Match Wits with Wolves,” and “I’ll Get Old Club Foot Yet!” were unconscious parodies of frontier yarns in which the trappers played the role of the sheriff going for his six-shooter or shootin’ iron whenever he saw a wolf.

The men who wrote these stories passionately believed they were serving humanity in the lower forty-eight states from this distant outpost. One of them, as if writing home to his family, said, “While I do my best to destroy all the wolves in the Ward Cove Game Refuge, the other animals go unmolested. On the roof of my cabin at Third Lake, the martin jump at night and the deer, unmolested, have become very tame, seeming to sense that there are few wolves and that man bears no ill will.”

An Alaskan trapper named Lawrence Carson tracked a wolf that had dragged one of his traps more than twenty miles and found him hung upside down by the dragline on a steep hillside. He disentangled the wolf for the purpose of taking pictures, then shot him in the head. “Lobo died as he had lived, in defiance of all things that would dare to conquer him. His bloody career was ended, but even in death his fiery eyes and truculent jaws opened in a look of unremitting hate. Lobo, king of his domain—and rightly a king he was called—was dead.”

But Carson’s thoughts reveal the ambivalence in some of these men, for he continues:

“As I looked at his lifeless form, a feeling of condonation came over me. Even though he had been a wanton destroyer of wild life and ill-deserving of mercy, somehow I felt sorry that he was gone. I wondered if the great mountains and deep silent valleys that had been his range would miss him. I wondered if at night, when the moon hung low like a great ball of fire, the dark shaggy spruce trees would miss his wild, deep-throated call. Something has been taken away that would never be put back in the scheme of things. Somehow I felt as if there was an irreparable loss. The well-known axiom had again asserted itself; the sport and fun were not in the kill, but in the chase.”

Those who stayed on in Alaska eventually wrote for the very same audiences of their fondness for the wolf, debunking the old stories of wolves killing people, and saying not much at all about how cute the deer were. One ended his story by saying he would like to spend his last years with wolves. He wrote, “I think I could enjoy the companionship of that magnificent creature more fully than any other creature on earth.”

The O’Connor-type hunters whose hatred of wolves was gospel gave way in the 1960s to a more “enlightened” hunter, who spoke of the beneficial value of the wolf in balancing wild ecosystems, but who still wanted to kill him. The president of the Boone and Crockett Club, a national hunters’ organization, said: “If more factual information can be widely disseminated to the general public as well as to sportsmen and conservationists perhaps this magnificent animal can yet attain his well-deserved status as a useful and highly important big game trophy animal.” He was no longer a varmint; he was big game. The justifications are endless.

Without airplanes no one deliberately hunts wolves anymore—they are too hard to find from the ground. (Whatever sport there may be in wolf hunting, in the sense of earning a right to kill, is probably down there on the ground with the trapper who does it for a living. He works alone over long distances during a harsh season. He has to know something about wolf habits and a lot about the territory.) The wolf becomes a big game trophy animal today only when someone is lucky enough to see one while he is hunting something else. This kind of wolf hunting brings us to the present day.

Big game hunting in North America became popular after World War II. Books and articles about the romance of the sport in Alaska and Canada were suddenly everywhere. The formula for these stories was always the same: the author flew to the north country, explored widely with a guide, shot record numbers of animals, and sat around a campfire lamenting the loss of North America’s best trophy animals to wolves, Indians, and Eskimos. It was agreed that if something wasn’t done to thin the wolf population the herds would soon be gone.

One such book, From Out of the Yukon by James Bond, contains the requisite scenes and sentiments. It is worth reviewing not so much for its appeal to armchair adventurers as for the portrait it paints of the wolf and the hunting philosophy it endorses.

Around the campfire one evening Mr. Bond suggests it’s not the wolves but excessive human hunting that is to blame for the depletion of the game herds. Everyone agrees. The solution they arrive at is twofold: first, increase the wolf bounty and get furriers to raise the price of wolf pelts to encourage more wolf trapping; second, “encourage all hunters to be good sportsmen and not shoot more than they need.”

In his north country adventures Mr. Bond encounters wolves twice. The first time he can’t get a clear shot but the guide does. “Well, I do not have to tell you,” he writes, “that I badly wanted that big black devil for my trophy room, but I am glad Norman killed it, for it means one less wolf in the country.”

The second wolf he meets, one howled up by the guide, he cripples and as he approaches, he thinks: “What excitement! These wolves had no conception of man.” After he has killed the wolf, Mr. Bond inspects the head. “I was really amazed to find the numerous and tremendous muscles in the head and neck of this great wolf. They could only have developed through usage—ripping and tearing at our game animals… . It pleased me greatly to see this leader of destruction lying dead on the ground before me.” The dimensions Mr. Bond reports for the wolf, typically, exceed those of any wolf on record.

I do not think men thoughtlessly kill wolves; they have reasons for doing so. Prime among them is the belief that they are doing something deeply and profoundly right. Whatever arguments are put forth—predation on big game, wolves are cowards and deserve to die—all seem rooted in the belief that the wolf is “wrong” in the scheme of things, like cancer, and has to be rooted out.

Killed for bounty by aerial hunter in Minnesota in the 1960s

It is a convention of popular sociology that modern man leads a frustratingly inadequate life in which hunting becomes both overcompensation for a sense of impotence and an attempt to reroot oneself in the natural world. As man has matured, the traditional reason for hunting—to obtain food—has disappeared, along with the sacred relationship with the hunted. The modern hunter pays lip service to the ethics of the warrior hunter—respect for the animal, a taboo against waste, pride taken in highly developed skills like tracking—but his actions betray him. What has most emphatically not disappeared, oddly, is the almost spiritual sense of identification that comes over the hunter in the presence of a wolf.

Here is an animal capable of killing a man, an animal of legendary endurance and spirit, an animal that embodies marvelous integration with its environment. This is exactly what the frustrated modern hunter would like: the noble qualities imagined; a sense of fitting into the world. The hunter wants to be the wolf.

The first time I understood this I was talking with a man who had killed some thirty-odd wolves himself from a plane, alone, and flown hunters who had killed almost four hundred more. As he described with his hands the movement of the plane, the tack of its approach, his body began to lean into the movement and he shook his head as if to say no words could tell it. For him the thing was not the killing; it was that moment when the blast of the shotgun hit the wolf and flattened him—because the wolf’s legs never stopped driving. In that same instant the animal was fighting to go on, to stay on its feet, to shake off the impact of the buckshot. The man spoke with awed respect of the animal’s will to live, its bone and muscle shattered, blood streaking the snow, but refusing to fall. “When the legs stop, you know he’s dead. He doesn’t quit until there’s nothing left.” He spoke as though he himself would never be a quitter in life because he had seen this thing. Four hundred times.

It does not demean men to want to be what they imagine the wolf to be, but it demeans them to kill the animal for it.