YOU DO NOT HAVE to explain to anyone that wolves and sheep don’t get along. When Lord Byron wrote in The Destruction of Sennacherib that “the Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold,” he did not leave his readers struggling for his meaning, and when Chaucer wrote in The Parson’s Tale of “the devil’s wolves that strangle the sheep of Jesus Christ,” his Christian audience did not wonder that it should be wolves who do the Devil’s work. War correspondents writing of German wolfpacks prowling the North Atlantic clearly conveyed the Allied perception of the Third Reich as a creature of abominable cruelty and greed preying on Europe. And people reading of The Wolf Lair, a fanciful Allied name for the Führer’s military retreat in eastern Prussia, found it very apt. Had someone noted, further, that the name Adolf was a contraction of Edel-wolf, the noble wolf, the reader would have understood.

The human mind entertains itself with such symbols and metaphors, sorting out the universe in an internal monologue, and I think it delights in wolves. The wolf is a sometime symbol of evil, and the mind dotes on distinctions between good and evil. He is a symbol of the warrior, and we are privately concerned with our own courage and nobility. The wolf’s is also a terrifying image, and the human mind likes to frighten itself.

The symbolism and metaphor of wolf imagery is not vast, but it is potent. It is rooted in the bedrock of the soul. The tradition of the wolf as warrior-hero is older than recorded history. The legends of Romulus and Remus and other wolf children point up another ancient image, that of the benevolent wolf-mother. The deaths of those taken for werewolves and burned alive in the Middle Ages represent yet another, focusing negative feelings about the wolf. As old as these, though not as widespread outside Europe, is the sexual imagery associated with wolves, the Latin lupa for whore and female wolf, the wolf whistle, and the French idiom elle a vu le loup. On the walls of a Roman catacomb the story of the compromising of the voluptuous Susanna by two elders is depicted as a sheep crowded by two wolves.

I wrote above of the wolf as a symbol for twilight. Other writers have suggested, and I agree with them, that the wolf was a symbol reflecting two human alternatives at war: instinctual urges and rational behavior. In Hesitant Wolf and Scrupulous Fox, Karen Kennerly says the wolf is the creature who is most like us in animal fable. “Out of phase with himself,” she says, “he is defeated alternately by hubris and naiveté… . He becomes the irreconcilability between instinct and rational thought.” His attempt to live a rational life is defeated by his urge to behave basely. Thus, the human and bestial natures.

Throughout history man has externalized his bestial nature, finding a scapegoat upon which he could heap his sins and whose sacrificial death would be his atonement. He has put his sins of greed, lust, and deception on the wolf and put the wolf to death—in literature, in folklore, and in real life.

The central conflict between man’s good and evil natures is revealed in his twin images of the wolf as ravening killer and (something we have not examined before) as nurturing mother. The former was the werewolf; the latter the mother to children who founded nations.

Today we, like most people in history, are favorably inclined toward surrogate wolf-mothers, even if we consider such things folklore. But we have lost track of werewolves in the twentieth century. Werewolves were a stark reality in the Middle Ages. Their physical presence was not doubted; at a symbolic level the werewolf represented all that was base in man, especially savagery and lust. If, as Kennerly and others suggest, to love what was good in the wolf was really to express self-love, and to hate what was evil in the wolf was to express self-hate, then the hunting down of werewolves was simply the age-old attempt to isolate and annihilate man’s base nature. That it went on for so many hundreds of years indicates an abiding self-hatred in man.

Reflection on what happened in the Great Plains in America during the wolf wars reveals a certain amount of self-hatred, but we are drawn back inevitably to the Middle Ages. At a time when no one knew anything about genetics, the idea that a child suffering from Down’s syndrome—small ears, a broad forehead, a flat nose, prominent teeth—was the offspring of a wench and a werewolf was perfectly plausible. The Middle Ages were a melancholy time, accurately reflected I think in the surreal and grotesque imagery of painters like Heironymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel the Younger; a time of famine, of endless wars, of epidemic disease, of social upheaval. Civilization was not as precious as it is to us today. The temptation to strike back at a painful world must have been strong. There were herbs to be purchased. There were Faustian pacts that could be made. Wanting to be a werewolf, in other words, was somehow understandable. In a history of witchcraft in the Middle Ages, Jeffrey Russell has written that some peasants were moved by “the Promethean urge to bend both nature and other people to their own ends … to obtain the objects of their pecuniary or amatory desire or to exact revenge on those whom they feared or hated.”

Given a depressed populace, a belief in werewolves, and the intimidation practiced by the court of the Inquisition, it is not surprising that people panicked and confessed precipitously to being werewolves, to having committed crimes against nature. And it wasn’t just werewolves; in 1275 a deranged woman named Angela de la Barthe confessed to the Inquisition at Toulouse that she had given birth to a creature that was half wolf, half snake, and that she had kept it alive by feeding it human babies she stole. In 1425 in Neider-Hauenstein near modern Basel a woman was sentenced to death for consorting with wolves, on whom, it was alleged, she had ridden across the night sky.

The Middle Ages were years of very deep frustration for human beings, caught in the twilight between the Dark Ages and the Renaissance. It was the time of the wolf. And anger that men felt over their circumstances, they heaped on wolves.

The beast in the wolf.

But before the story of the werewolf can begin, another story must be told. There is a character in the bestiaries, L’homme sauvage, the wild man of the woods, whose path intersected the werewolf’s. The wild man was the product of an evolutionary synthesis of Pan and Dionysius, Roman

gods of the pasture and the harvest respectively. Dressed in a suit of bright, tattered cloth, he was a central figure throughout the Middle Ages in the ancient pagan midwinter celebrations. In that same tattered suit he later became the harlequin figure in the commedia dell’arte and also Shakespeare’s Caliban in The Tempest. A carnal, frivolous, somewhat slow-witted prankster most of the time, he was also thought of as a somber, almost ascetic loner, wandering the vast stretches of thick forests that lay between medieval settlements, eating berries, roots, and wild game. He shared the dank, dismal woods with religious and social outcasts and with the wolf, who stood as symbol for them all. Most importantly for our interest, the wild man was associated with acts of depravity and sexual indulgence. As his image began to diffuse in the 1400s and 1500s, these qualities were impressed on the werewolf.

The wild man, depicted in scenes such as the Rape of Proserpine (where he appears as Pluto), was widely popular. The art historian Richard Bernheimer, speculating on the vigor of the wild man’s survival through the ages, writes: “It appears that the notion of the wild man must respond and be due to a persistent psychological urge. We may define this urge as the need to give external expression and symbolically valid form to the impulses of reckless physical assertion which are hidden in all of us but are normally kept under control.”

And the historian Jeffrey Russell says in his Witchcraft in the Middle Ages: “The wild man, both brutal and erotic, was a perfect projection of the repressed libidinous impulses of medieval man. His counterpart, the wild woman, who was a murderess, child-eater, bloodsucker and occasionally a sex nymph, was a prototype of the witch.” The latter recalls the vargamors in Scandinavia, women who procured human victims for their wolf companions, frequently by promising sexual favors. Bernheimer’s and Russell’s statements both reflect the beast in search of a violent sexual connection. And indeed it is not surprising to find as a common theme, especially in the later Middle Ages (and still later more violently in pulp novels), men who became werewolves solely to avenge rejection by a lover. (It is rare that women become werewolves. When they do, it is almost always as a means to an end—to steal a child victim for a sabbat, for example.)

There are other places where the paths of the wild man and the werewolf cross. The Twelve Days between Christmas and Epiphany were the days of the wild man rituals in Europe and also the time when werewolves were supposed to be on a rampage. The men who dressed up to portray wild men during the celebrations were expected to drink to excess, to abuse women, to behave like Berserker, a fanatic cult of Teutonic warriors who dressed in wolf and bear skins. In the Baltic countries, in fact, their behavior was hardly distinguished from the rampages of the Wild Horde in Teutonic legend.

The wild man and the werewolf alike were metamorphosed from formidable forces in the pagan imagination, through the grotesque, almost psychopathic imagery of the Middle Ages, to become the derivative, often impotent and pathetic caricatures we find in movies and pulp literature today.

The legend of the werebeast is almost universal. In each country primitive beliefs in shapeshifting (the human ability to change to an animal form) combine with beliefs in sorcery to produce a fearsome local werebeast who goes about at night usually, but not always, slaying human beings. In Africa there were werehyenas, in Japan there were werefoxes, in South America there were werejaguars, in Norway there were werebears. In Europe there were werewolves.

The werebeast might be a sorcerer bent on killing an enemy, like the Navajo werewolf. He might be a victim under a sorcerer’s curse, wandering melancholy about the countryside, as was said of werewolves in White Russia. Or he might be benevolent and protective, like Alphouns, the werewolf of a twelfth-century romance, William of Parlerne, who acted as a protector to the rightful heir to the Sicilian throne. There is nothing inherently evil in the idea of shapeshifting, which is why some benevolent werewolf stories survive. But as the wolf came to stand more and more for the bestial, for the perverse, for evil in every form, the simple phenomenon of shapeshifting was overshadowed by the presence of a terrible creature that preyed on everything human and, in the most voyeuristic stories, engaged in a level of violence and sexual depravity that had not the remotest connection with any animal but man himself. It is important to keep this in mind, because in looking to the “werewolves” of primitive ages there is a tendency to telescope backward ideas that only developed much later.

The werewolf of our legends took form, in part, in Greece. At the tip of the Balkan peninsula lies a landmass known as the Peloponnesus and at its center is a region known as Arcadia. According to Greek legend, Lycaon, the son of Pelasgus, civilized Arcadia and instituted the worship of Zeus there. Word later reached Zeus that Lycaon’s many sons were lax in their religious duties and arrogant toward their father. Zeus decided to visit them, disguised as a day laborer, and see for himself.

When he came to Lycaon’s house he was welcomed, but Lycaon’s sons convinced their father to serve the stranger human flesh, to see if he might be Zeus in disguise. Nyktimos, one of the sons, was killed and his entrails were mixed with the meat of sheep and goats. A bowl of this was then set before the god. Zeus hurled the bowl to the floor, changed Lycaon and all his sons into wolves (except Nyktimos, whom he restored), and stormed out.

Still angry over Lycaon’s blasphemy and incensed at the ways of men in general, Zeus unleashed a flood to drown them all. Deucalion’s flood (named for the man who built an ark and escaped) destroyed Lycaon and his sons, but some survivors who later emigrated to Arcadia ritually killed people to satisfy the gods. These survivors were former residents of the country around Mount Parnassus. Ironically, they had been awakened on the night of the flood by the howling of wolves who led them to high ground. An Arcadian practice in later centuries, according to the geographer Pausanius, was to prepare a meal like the one served Zeus and set it before a group of shepherds. The one who found human entrail in his bowl ate it, howled like a wolf and, leaving his clothing hung on an oak, swam across a stream where he remained in a desolate region as a werewolf for nine years. If in that time he ate no human flesh he regained his human form.

This is the story Pliny tells in the Historia naturalis. He adds that an Arcadian youth named Damarchos who had become a wolf under these circumstances abstained from human flesh, regained his form, and later won a boxing match in the Olympic Games. Socrates alludes to the story in Plato’s Republic when he says that a beneficent ruler (like Lycaon) is destined to become a tyrant if ever he tastes human flesh, that is, if he should ever arrange to have a political enemy murdered.

Lycaon’s name is preserved in the scientific name for the Eastern timber wolf, Canis lupus lycaon, and in the name for a kind of delusion and melancholy in which a person believes himself to be a wolf but retains his human form—lycanthropy.

The origin of this story is vague. Most scholars shy away from regarding Zeus as a wolf-god to whom humans might have been sacrificed. They hold that he was a god of light and that the terms were, again, confused in Greek. The element of human sacrifice and the inclusion of wolves in the story may have come about like this. The Arcadians were an agricultural people. It may have been the custom for the reigning king to take his own life to propitiate the gods if the crops failed. In time, a modification of this practice was introduced whereby the king had someone else sacrificed in his place. To expiate his guilt at this, the king shared responsibility for the murder with those whom he invited to a ritual meal. One of this number was then chosen by lot to atone for the sin by being banished from human society—for nine years.

This is all plausible and probable. It may have been, too, that later the cult of Zeus was grafted onto an existing wolf cult in Greece that actually sacrificed human beings in an effort to placate wolves (the Arcadians kept flocks and the Peloponnesus was thick with wolves). Deucalion’s flood, then, may represent the civilizing Hellenistic invasion that wiped out the practice of human sacrifice, leaving it to survive only in isolated places like Arcadia.

Whatever its origin and meaning, the story offers a perception of the wolf as bestial man who can, if he controls his animal appetite for nine years, attain the status of a human being. The connection between the outlaw or outcast and the wolf is also made clear.

We draw most of our werewolf tradition from northern and eastern Europe, but I chose this Greek legend to begin this section on werewolves because it is so succinct. It grew up among people who probably considered wolves enemies, and it voices one of the most persistent taboos in the folklore of Western man, that against eating human flesh. The wolf seen eating human carrion on a medieval battlefield was reviled because he was held to be sufficiently endowed to know that what he was doing was wrong but was base enough to do it anyway. The quintessential sinner.

A poignant aspect of the wolf’s predicament emerges here. In a hunter society, like that of the Cheyenne, traits that were universally admired—courage, hunting skill, endurance—placed the wolf in a pantheon of respected animals; but when man turned to agriculture and husbandry, to cities, the very same wolf was hated as cowardly, stupid, and rapacious. The wolf itself remains unchanged but man now speaks of his hated “animal” nature. By standing around a burning stake, jeering at and cursing an accused werewolf, a person demonstrated an allegiance to his human nature and increased his own sense of well-being. The tragedy, and I think that is the proper word, is that the projection of such self-hatred was never satisfied. No amount of carnage, no pile of wolves in the village square, no number of human beings burned as werewolves, was enough to end it. It is, I suppose, not that different from the slaughter of Jews at the hands of the Nazis, except that when it happens to animals it is easier to forget. In the case of the werewolf, however, it must be recalled that we are talking about human beings.

Herodotus wrote that the Neurians who lived in present-day western Russia changed into wolves for a few days once a year. The Neurians were hunters who probably had a totemistic relationship with wolves and wore wolf skins in an annual ceremony; but this mention by Herodotus is commonly cited as evidence that early on there was a race of werewolves. Pliny and others mention a wolf cult at Mount Soracte near Rome. The members danced in wolfskins and walked through fire carrying the entrails of sacrificial animals. It is not hard to see how the propitiation of wolves who threatened flocks, combined with older totemistic relationships, easily created the impression of werewolves hundreds of years later.

The story of the werewolf in Petronius’s Satyricon is often cited as evidence of a belief in werewolves in Rome at the time of Christ, but people tend to forget that the story was written to entertain. Any historical value is fortuitous. Petronius’s tale is of a man who changes into a wolf and attacks a herd of cattle before being driven off with a pitchfork wound in the neck. The narrator in the story later finds his good friend suffering from a pitchfork wound in the same place. It is convincing evidence that he is, in Petronius’s word, a versipellis, a skin changer. (This element—a wolf is wounded and a human being is later found with a similar wound—was the basis of proof in many werewolf trials.)

The werewolf stories from northern Europe typically were more robust, adventurous, and inventive than these classical Greek and Roman stories. Olaus Magnus writes in his History of the Goths that at Christmas werewolves gathered together for drinking bouts and forcefully entered houses for the purpose of raiding the wine cellar. The element of debauchery he introduced into the lore of the werewolf was probably adapted from the Teutonic legend of the Wild Horde that rode out at night astride wolves. Or from tales of the Berserker. That it took place at Christmas could mean Magnus’s story was based on wild tales of the pagan midwinter festivals celebrating the return of the sun, or that it was Christianized so that the wolves were drunk on Christ’s birthday, thus adding to the sacrilege.

Magnus also wrote that the werewolves of Livonia gathered at Christmas and, like the Arcadian werewolves, swam across a body of water to effect their transformation. They remained werewolves for twelve days, until the Epiphany, drank heavily, and at some point, says Magnus, gathered at the walls of an old castle where they engaged in leaping contests. The ones who couldn’t jump the wall were beaten by the Devil.

Debauchery and sacrilege, which became common in werewolf stories later, are not the themes of early Teutonic werewolf tales. Violence is, however. In the Icelandic saga of the Volsungs, King Volsung’s daughter Signy marries a king named Siggeir. Siggeir, whose mother is a werewolf, turns around and kills Volsung and puts his ten sons into stocks to feed his mother. The tenth son, Sigmund, escapes and Signy later bears him a son. One day Sigmund and his son come on a house in the woods where two men are sleeping. Hung on the wall over the head of each is a wolfskin. Sigmund believes the men are werewolves and that by donning the skins he and his son will be transformed for nine days. They put the skins on, agree not to kill more than seven men each, and go their separate ways. But the son kills eleven men and his angry father, still in wolf form, attacks and wounds him. His anger abated, filled with remorse, the father nurses his son’s wounds. On the ninth day they regain human form, throw the wolf skins on a fire, and agree never to do such a thing again.

The Livonian wolves at the leaping wall.

Marie de France, writing in the latter part of the twelfth century, created the prototype of the sympathetic werewolf in a romantic narrative poem, or lay, called Lai du Bisclavret, “Bisclavret” being the name by which the werewolf was known in Brittany. In the story a French baron, besieged by his anxious wife, finally tells her that when he disappears for three days every week it is to roam the woods as a werewolf. Terrified, the wife induces her lover to follow the baron into the woods and steal his clothes. Without the clothes her husband cannot return to human form. This the lover does, and he and the wife are married while the baron’s friends mourn his disappearance.

A year later the king is out hunting when his dogs overtake Bisclavret. The big wolf takes the king’s stirruped boot in his paws and implores with his eyes for the dogs to be called off. The king orders the dogs away and returns home with the wolf, who becomes his tame and loving companion. Later, traveling in the vicinity of the baron’s old castle with the wolf and his retinue, he is visited by the baron’s wife. The wolf goes mad when he sees the woman, biting off her nose. The story of her betrayal comes out. She and her lover are banished and, with the return of his clothes, the baron regains his form and returns to his castle. The werewolf of Marie de France’s story is an involuntary one, a human being under a curse. By the time of the werewolf trials in the Middle Ages, an amalgamation of folklore and superstition had created such distinctions among types of werewolves and a body of lore on how transformations were affected and reversed. By then, too, a curtain of evil separated werewolves from their relatively benign origins. The imitative magic of the Pawnee wolf scouts had been reduced, to voodoo.

An Irish priest was on his way from Ulster to Meath when he was approached by a wolf who spoke to him. The wolf assured him that there was nothing to fear, it was just that his wife was dying and he wished the Last Rites for her. They were both victims of a curse pronounced on the people of Ossory by Saint Natalis, according to which every seven years two people had to don wolfskins and live as wolves. The priest was terrified but he followed the wolf into the woods. At some distance he found a female wolf lying ill beneath a tree. The priest stood frozen, unable to act. The wolf reached down and rolled back the female’s wolf skin and the priest saw underneath the bony torso of an old woman. No longer afraid, he heard her confession and gave her the Last Rites.

The wolf accompanied the priest back to the highway, thanked him profusely and told him that if he lived out his seven years he would search the priest out and thank him properly.

The priest went on his way, satisfied that he had done right.

—GIRALDUS CAMBRENSIS, 1188

Some werewolves became so voluntarily. A voluntary werewolf was a sorcerer who, typically, got the power of transformation from the Devil in a Faustian exchange. His transformation could be effected by donning a wolf skin or magic belt, by sipping water from the print of a wolf, by ingesting roots, by applying ointments, by drinking from certain streams, by charms, or by some action, such as swimming across a certain body of water or rolling around on the ground (epileptics were often taken for werewolves). An involuntary werewolf came to his form as the result of a family curse or a spell cast by a sorcerer—out of hate, for pay, or at the Devil’s behest. A person also became a werewolf when he was born to a certain tribe, like the Seiar of Hadramaut, a Semitic people, or the residents of Ossory in Ireland. There is a Polish belief that a belt of human skin laid across the threshold of a house where a wedding is taking place will change all who step over it into wolves. And it was a general belief in Europe that those unfortunate enough to be born on Christmas Eve would be werewolves. Slavs believed those born feet first became werewolves, Scandinavians that the seventh girl born in a row to a family did. According to a legend from the Caucasus, a woman who committed adultery became a werewolf for seven years.

Elliot O’Donnell, a modern English author, writes in his book Werwolves that werewolves could be told “by the long, straight, slanting eyebrows, which meet in an angle over the nose, sometimes by the hands the third finger of which is a trifle longer; or by the fingernails, which are red, almond shaped and curved; sometimes by the ears, which are set low and rather far back on their head; and sometimes by a noticeably long, swinging stride, which is strongly suggestive of some animal.” In human form the werewolf might show a vestigial tail between his shoulder blades and the Russians believed he had bristles under his tongue. In wolf form the werewolf was supposed to be tailless.

A werewolf regained human form by putting his clothes back on, taking the wolf skin off, or slipping the buckle of his wolf belt to the ninth hole. A werewolf could be cured if his wolfskin were burned, if he were slashed across the forehead three times and bled in a prescribed manner, or if he were addressed by his Christian name while being denounced as a tool of Satan. A werewolf named Peter Andersen in Denmark was apparently cured when his wife threw her apron in his face as he attacked her, as he had instructed her to do. Another was cured when his son threw a hat at him. They could also be caught and bound and exorcised with potions. According to O’Donnell, a common one was one-half ounce of sulfur, one-half ounce of asafetida or devil’s dung, and one-quarter ounce of castor in clear spring water. Another was one-quarter ounce of hypericum compounded with three ounces of vinegar. These mixtures were used in sabbatlike settings by priests or friends of the victim, who was burned and beaten by young girls with ash switches in the process. Mountain ash, along with rye and mistletoe, were considered protection against werewolves.

The werewolf phenomenon might have languished in the folklore of the countryside but for two things: the wolf, Canis lupus, posed both a real and an imagined threat of major proportions in the medieval mind; and the legend of the werewolf suited the needs of the Inquisition, which did more to sustain the belief by fanatical persecution than any other agent or institution.

The Christian Church was historically embattled from the beginning. Without an enemy to fight, it had no identity. Until the time of the Christian emperors, the enemy was the state. Then it was the paganism of northern Europe. Then came the Crusades and the war against the infidel. After the reign of Charlemagne, the enemy was increasingly heresy, particularly reformism. By the time the Inquisition begins in the thirteenth century the perception of the Church about the enemy is clear: he is the heretic. Behind the heretic, like a puppet master, is the Devil. The wolf in the sheepfold. Once only a vague idea for theologians, the Devil has by now become a full-blown personality. As the Middle Ages begin he is a superhuman presence, as real as hogs tearing a child apart in a pigsty. The heretic is the means to destroy Christ’s Church on earth. Only by destroying the heretic could the enemy be vanquished. Witches, sorcerers, and social reformers became the most visible enemies of the Church, and the most dangerous, because they could galvanize the ecclesiastical and political revolt incipient in the malaise of the Middle Ages. Witches, sorcerers, and the so-called possessed were brought before a mock court, which denounced them as heretics and killed them.

Allegations of witchcraft and sorcery—running around the countryside in a wolf skin killing children, or sending a pack of wolves to decimate the flocks of a good Christian—were charges rather easily sustained. Fundamental nonsense was taken for irrefutable evidence. The idle word of a neighbor, the gibberish of a village idiot, a shaving cut that showed up the morning after someone claimed to have driven off a wolf with a sharp stick—for these reasons and less thousands died at the stake. The hysteria and intimidation generated by swift, absolute, and irrevocable condemnation on the basis of mere shreds of evidence is what kept the Inquisition alive—and fed it victims. People wanted society to work smoothly, to be rid of whatever ailed it. They were easily drawn to simplification, to believing that werewolves, tearing around the countryside on the Devil’s business, caused deformed children, disruptive harassment by the ruling classes, general ill fortune due to God’s wrath, grisly murders, and so on. It was no coincidence that simultaneously there was a drive to wipe the wolf out in Europe, mounted as “the crying need of a civilized people.”

The wolf and the look-alike werewolf became everyone’s symbol of evil. (Oddly, the werewolf was hardly a concern of the Church before this time. The archbishop of Mainz had chided the Saxons in a sermon in 870 for a superstitious belief in shapeshifting. By 1270, however, the werewolf was the incarnation of the Devil and not to believe in the existence of werewolves was heretical.) The shepherds and the priests, with their respective flocks, hated wolves; the noble was bent on ridding his country of them to effect an air of civilization; Edgar of England imposed an annual tribute of three thousand wolves on the king of Wales; the landlord with his investments in livestock denounced them; the wives of the emerging middle class called the prostitutes wolves because they thought of them as wenches consuming the souls of their sons.

Terrorized by the number of sorcerers and witches the Inquisition found in their very midst, people responded in an orgy of accusation and counteraccusation. Historians of the period write that the hysteria was simply epidemic.

The excessive persecution of werewolves—where a witch might be hung, a werewolf was more often burned alive—had a formal basis. The supposition was, first, that sorcerers went about disguised as wolves because the wolf was the animal most hateful to good men; Church doctrine proclaimed that no sorcerer could harm men unless he were in contractual league with the Devil; the wolf, as the Devil’s dog, became the form to do his work in. This symbolic logic was formalized in one of the most odious documents in all human history, the Malleus Maleficarum, published in 1487. Its title, Hammer of Witches, derives from a title sometimes bestowed on Inquisitors, Hammer of Heretics. One of the purposes of the book was to refute in tedious scholastic fashion every objection to the existence of werewolves.

The Malleus addressed itself mainly to proofs that those who became werewolves were in concert with the Devil and that the Church was acting properly in condemning them. From its pages superstition and folklore received an intellectual underpinning that made belief in werewolves not just a matter of Church doctrine but the intellectual fashion of the day. (Abjuring wolves, of course, had never really been out of fashion.) In a couple of places, the Malleus speaks directly about werewolves. Quoting both Leviticus (“If you don’t keep my commandments I will send the beast of the field against you, who will consume your flocks”) and Deuteronomy (“I will send the teeth of the beast down on them”), the Malleus states that wolves are either the agents of God, sent to punish the wicked, or agents of the Devil, sent with God’s permission to harass good men. (That there was no middle ground where the wolf was his own animal clearly reveals the perception of the time.) Witches can change men into wolves, though the transformation is actually an illusion in the eye of the beholder because only God Himself can transform. A real wolf (Canis lupus) possessed by the Devil commits the mayhem. This was scholastic hairsplitting; werewolves were as real as their dead victims—as real as the Devil as far as the Church was concerned. That the Devil could create illusions only with the permission of God was simply poignant theology; it maintained God’s supremacy over the Devil and gave purpose to human suffering. But, more importantly, to battle the werewolf brought one closer to God, and to burn the werewolf was to destroy a temple of evil in God’s name.

One wonders if anyone shuddered at the fatuous logic—perhaps the Malleus would not have appeared if there were not terrible doubts to assuage. It is a commonplace of history that men condone violence for righteous causes and then feel guilty about it. It is also true that those who condemn violence most severely are sometimes its greatest voyeurs. Immediately after the execution of Peter Stump in Germany on March 31, 1590, for murder, incest, rape, and sodomy in the form of a werewolf, a pamphlet appeared describing his crimes in detail and dwelling on their perversity. Today we cannot judge what role such voyeurism played in the vigorous pursuit of werewolves in the Middle Ages.

Werewolfry also gave the upper classes an excuse for a sort of general housecleaning of undesirables. The trial in the 1570s of a hermit named Giles Garnier, who lived in a cave outside Lyon, is a good example. A wolf had apparently killed some children in the area. Garnier was found one day scavenging a dead body in the woods to feed his family. In court, ignorant of his position at first, he was intimidated until he confessed to making a pact with the Devil, and to six or seven grisly child murders. He was burned alive without further ado at Dole, near Lyon, on January 18, 1573. Montague Summers, an eccentric pedant and modern apologist for the excesses of these witch-hunts, writes, “Hateful to God and loathed of man, what other end, what other reward could he look for than the stake, where they burned him quick, and scattered his ashes to the wind, to be swept away to nothingness and oblivion.” For all we know, this was the fortune of a man whose only crime was being a beggar.

A tailor who sexually abused children, tortured them to death; and then powdered and dressed their bodies was burned as a werewolf in Paris in 1598. Michel Verdun and Pierre Burgot were accused of sexual relations with wolves in 1521 and executed. Another famous French case involved a fourteen-year-old boy named Jean Grenier. He confessed to being a werewolf, indicting also his father and a friend of his father. His formal confession is gory, full of religious and sexual perversion. Condemned to death on September 6, 1603, he was transferred instead by recommendation of clemency to a Franciscan friary in Bordeaux where he spent the next eight years running around on all fours, completely demented, physically deformed, and pathologically attached to wolf lore.

Of what, exactly, he was a victim is a question that hurts the human soul.

Among all the heretics and political enemies of state who were marched through the courts and condemned as werewolves were an unending number of the wildly insane, the epileptic, the simple-minded, the pathologically disturbed, and the neurotically guilt-ridden. They were condemned as society’s enemies, but their connection with wolves was tenuous in the extreme and that with werewolves highly imagined.

The point of examining all this is that these very same trials, this period of hysteria, fixed in the human imagination the ghoulish and sexually perverse picture of the wolf/man that turns up hundreds of years later in such pulp novels as The Werewolf of Paris and worse. Montague Summers, immersed in the imagery of that time, writes: “The werewolf loved to tear human flesh. He lapped the blood of his mangled victims, and with gorged reeking belly he bore the warm offal of their palpitating entrails to the sabbat to present in homage and foul sacrifice to the Monstrous Goat who sat upon the throne of worship and adoration. His appetites were depraved beyond humanity. In bestial rut he covered the fierce she-wolves… .” It is this twisted view from the Middle Ages that still feeds the human imagination, that preserves an image of the wolf that is not only without foundation in the natural world but almost completely a projection of human anxiety.

The werewolf has no counterpart in the sense that there is no strongly pervasive image of the wolf as a force for good. But the body of folk belief and folklore bearing on wolf children—human beings raised by nurturing female wolves after they have been abandoned by their parents—is, in a sense, the complementary image.

The history of wild, or feral, or wolf, children is long in legend and fact. The most famous, Romulus and Remus, are an enigma. Plutarch in The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans tells us that the most widely believed story of that time (the first century) was that they were the twin sons of a woman named Ilia, or Rhea, or Silvia. She was a Vestal Virgin, and when the children were born—Mars is supposed to have been their father—they were banished to the wilderness. A swineherd named Faustulus who was charged with taking them away took them home instead. His wife was rumored to be a loose woman (the Latin for both “prostitute” and “she-wolf” being lupa is given as the possible source of confusion). Other versions have the twins spending some time with wolves before Faustulus rescues them. The founder of the Turkish nation was also supposed to have been raised by wolves.

Rousseau wrote of the wolf child of Hesse, who turned up in 1344. Nine animal children—sheep children, bear children, cow children, and pig children—were classified Homo ferus by Linnaeus in 1758. He and others described nearly forty such children before the end of the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century there came a stream of reports of wolf children from India, and of baboon children, gazelle children, and monkey children from Africa.

WOLF GIRL

Although stories of wolf children in America are rare, there is a story told in Texas about a wolf girl who grew up on Devil’s River, north of present-day Del Rio. The girl was, according to the story, born in May 1835 at the confluence of Dry Creek and Devil’s River. The mother, Mollie Pertul Dent, died in childbirth and the father, John Dent, was killed in a thunderstorm at a ranch miles distant, where he had ridden for help. The child was never found, and the presumption was that she had been eaten by wolves near the Dents’ isolated cabin.

In 1845, a boy living at San Felipe Springs (Del Rio) reported seeing “a creature, with long hair covering its features, that looked like a naked girl” attacking a herd of goats with several wolves. Similar reports were made by others during the ensuing year and Apache stories told of a child’s footprints having been found a number of times among those wolves in that country, and so a hunt was organized.

On the third day of the hunt the girl was cornered in a canyon. A wolf with her was driven off and finally shot when it attacked the party. The girl was bound and taken to the nearest ranch, where she was loosed and closed up in a room.

That evening a large number of wolves, apparently attracted by the girl’s loud, mournful, and incessant howling, came around the ranch, the domestic stock panicked, and in the melée the girl escaped.

She was not seen again for seven years. In 1852 a surveying crew exploring a new route to El Paso saw her on a sand bar on the Rio Grande, far above its confluence with Devil’s River. She was with two pups. After that, she was never seen again.

That is the story they tell.

These children were collectively referred to as wolf children because they were thought to have been raised by wild animals and because they behaved, in the eyes of human observers, like wild wolves. They hated to wear clothing, they had a penchant for raw meat, sought darkness during the day and roamed, instead, at night. They howled, ripped the flesh of those who tried to care for them, peeled back their lips to indicate displeasure, panted when they were hot, and ran around on all fours. It required only the barest stretch of the imagination, if such a child was found in the woods where there were wolves, to believe that the child had been raised by them.

Let me return to Jean Grenier, the disturbed child whose sentence was commuted. There is another, apparently factual, side to werewolfry that can be examined and that is the belief in lycanthropy as a pathological condition of melancholia and delirium, which has nothing to do with spells, the Devil, or eating human flesh. The idea has had some support among psychologists, but no case of lycanthropy can be clearly isolated from hysteria and superstition. Jean Grenier may have been such a victim. A man named Pierre de Lancre, who visited Grenier a year before he died, reported that he was lean and gaunt, that his hands were deformed, his nails like claws, and that he ran with great agility on all fours and ate rotten meat.

Had he turned up two hundred years later, Jean Grenier might have had a different fate. Had he in fact fallen into the hands of a gifted French teacher named Jean Itard—as did Victor, the wild boy of Aveyron—Grenier might have left us an explanation of others like him.

In the 1950s at the Sonia Shankman Orthogenic School of the University of Chicago, psychologists were treating nineteen children like Grenier. Some of them built dens in the corners of their rooms into which they crawled to eat the raw food they preferred. One of them, a girl, attacked one of the staff repeatedly, and so savagely that the woman required medical attention twelve times in as many months. The children licked salt for hours at a time and loped about the corridors at night, apparently with some pleasure. These, however, were not children rescued from the woods. They all came from middle-class homes in America. They were severely autistic.

The notion of the wolf child, a child actually raised by wolves, is a widespread belief. Because the wolf children described by various writers were all probably autistic or schizophrenic, suffering either congenital or psychological problems or both, the issue of whether authentic wolf-raised children ever existed seems a hopeless, not to say pointless, inquiry.

That people believed such things happened is undeniable, however, and it is not hard to see how such an idea took hold. Wolves likely did steal small babies occasionally, especially in India where they were left untended in the fields. But whatever ill they might have believed of wolves, most people also believed they were devoted and affectionate parents. It was quite plausible that wolves would care for children. Most cultures were aware that some animals, goats for example, nursed human infants, just as humans nursed young animals—puppies often—when the mother died.

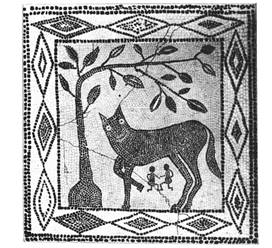

Victor, the wild boy of Aveyron.

Victor of Aveyron, the most famous of all feral children, was humanely treated for years by the physician and speech therapist Jean Itard. Itard must have been a man of enormous energy and patience, and tremendous kindness. His success with Victor, who demonstrated most of the symptoms of so-called wolf children, was limited. The boy never learned to speak and he was confused by his sexual desires. He died at the age of forty. Itard’s care of the boy, and his request of the French government that such children should not be abandoned in future as hopeless cases, is one of the most touching episodes in the literature of human care.

But the case of the rehabilitation of two Indian feral children, Amala and Kamala, presents us with something different. It is the only modern record which offers evidence of a direct link between wolves and wild children.

The Reverend J. A. L. Singh first saw Amala and Kamala about dusk on a Saturday, October 9, 1920, outside the village of Godamuri, seventy-five miles southwest of Calcutta. He flushed three grown wolves from the base of an ant mound and inside, monkeyballed together in fear, he found two wolf cubs and two young girls. A few weeks later their den was excavated. Two of the three adult wolves present escaped. The third was shot. The two wolf cubs with the girls were sold in the market in Godamuri. Amala and Kamala (as they were later named) were placed in a cage in which they were unable to stand up and left in the care of a man who subsequently abandoned them. Singh returned five days later to find the girls lying in their own excrement, starving and thirsty. They were barely strong enough to suck water from the end of his handkerchief. After a seven-day journey wedged in the bottom of a bullock cart, they arrived at Singh’s orphanage on November 4.

Amala died a year later, at about two and a half. Kamala, who was about eight when she was found, lived to be about seventeen. She died on November 14, 1929, at the orphanage, of uremic poisoning.

Amala and Kamala behaved in the manner of the severely autistic children described above, biting and howling, eating raw meat, preferring darkness, insensitive to heat and cold, keen of ear and nose, poor of eye. Like Victor of Aveyron they had difficulty with language. The thing that distinguishes them from other so-called feral children is that Amala never walked upright and it was years before Kamala did. This could have been, as one psychologist suggests, a regression to infant crawling behavior caused by the traumatic effect of the first two weeks after the children were taken from the wolf den.

Saint Ailbe, a sixth-century Irish bishop, was born the son of a slave girl. Shortly after his birth he was taken out and deposited in the wilderness by order of his mother’s owner. A wolf took compassion on him and cared for him until a huntsman found him. Years later, when he was Bishop of Emily, a gray wolf pursued by hunters ran into his house and laid her head on his lap.

“I will protect thee, old mother,” said the bishop, drawing his cloak around the old wolf. “When I was little and young and feeble, thou didst nourish and cherish and protect me, and now that thou art old and gray and weak, shall I not render the same love and care to thee? None shall injure thee. Come every day with thy little ones to my table, and thou and thine shall share my crusts.”

The diary kept by the Singhs and a book written in praise of their work by a physician reveal that the Singhs were primarily concerned with civilizing Kamala by seeing to it that she wore clothing, ate with utensils, and attended regular religious services. They seemed less concerned with discovering her as a person.

The Singhs divided Kamala’s actions into two categories: “wolf” and “human.” They judged her progress by how many wolf ways disappeared and how many human habits were inculcated. It was the Singhs’ orientation that Kamala had come to them as a bad creature and that she had to be turned into a good creature. Making a creature of God out of a creature of the Devil, in fact, is a note struck often in the diary. For all their kindness, there are elements of real barbarism in the Singhs’ treatment. They shaved Kamala’s head because they didn’t like her to look “dirty.” They bound her up so tightly in a loincloth in an effort to make her cover her genitals that she could not get it off to relieve herself.

There is a revealing conceit in the Singhs’ diary. Mrs. Singh gave Kamala a backrub every morning and when Kamala responded by nuzzling her, she would note in the diary that Kamala was beginning to show “human affection.” The first conceit, that such a demonstration of affection is uniquely human, is of course silly. The subtler conceit is that it was Mrs. Singh’s decision to give Kamala the rubdown. Wolves in captivity routinely solicit scratching and other tactile attention from human beings.

Amala and Kamala could have been severely disturbed children, abandoned by their parents, who stumbled on the wolf den as a place of refuge. Such children, in fact, do show an uncommon fondness for animals, particularly dogs. (Singh says he saw the girls at the wolf den some days before he took them out, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they were living there.)

There is no way to verify this story, although many scientists of the time believed Singh.

Why we should believe in wolf children seems somehow easier to understand than the ways we distinguish between what is human and what is animal behavior. In making such distinctions we run the risk of fooling ourselves completely. We assume that the animal is entirely comprehensible and, as Henry Beston has said, has taken form on a plane beneath the one we occupy. It seems to me that this is a sure way to miss the animal and to see, instead, only another reflection of our own ideas.

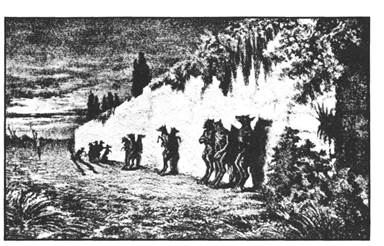

Mythic roots—the benevolent wolf mother, with Romulus and Remus

The sense that there has to be a strong tradition of the benevolent wolf in literature, in art, or in folklore is a modern wish that must go wanting, for such a figure simply does not exist. There are benevolent wolves, and wolves that befriend those who treat them ill in literature, but not wolves who nurture, from whom people draw sustenance as perhaps Romulus and Remus did prior to their founding Rome.

But I think, somehow, that looking for the wolf-mother is the stage we are at now in history. If we go back to the time of Lycaon and follow the development of the wolf image through the Dark and Middle Ages to the present, the overriding impression is that of a sinister creature. But in the twentieth century, whether out of guilt or because we have reached such a level of civilization as to allow us the thought, we are looking for a new wolf. We seem eager to be corrected, to know how wrong our ideas about wolves have been, how complex the creature really is, how ultimately unfathomable. What we are looking for, I think, is a way to return mystery to animals, and distance and selfhood, and thereby dignity. To quote Beston again, we want to feel that animals “are not brethren, they are not underlings, they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the web of life …”

Almost like errant children, we seem to want forgiveness from wolves. And I think that takes great courage.

It may be reasonable to expect most people to dismiss the notion of a nurturing wolf as a naive person’s referent, but that doesn’t seem wise to me. When, from the prisons of our cities, we look out to wilderness, when we reach intellectually for such abstractions as the privilege of leading a life free from nonsensical conventions, or one without guilt or subterfuge—in short, a life of integrity—I think we can turn to wolves. We do sense in them courage, stamina, and a straightforwardness of living; we do sense that they are somehow correct in the universe and we are somehow still at odds with it.

As our sense of sharing the planet with other creatures grows—and perhaps that is ultimately the goal of natural history—the deep contemplation of wolves may be seen as part of an attempt to nurture the humbler belief that there is more to the world than mankind. In that sense, the wolf-mother is just now upon us, in a role a quantum leap removed from Romulus and Remus.