ONE FALL AFTERNOON A few years ago I stopped in at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York to see a special exhibition of children’s literature. There were some early collections of Aesop and the animal fables of Jean de la Fontaine. And copies of the medieval epic Reynard the Fox, in which Isengrim the Wolf plays such a major role. But there was one thing I especially wanted to see: a presentation manuscript of Charles Perrault’s Histoires ou contes du temps passé, a collection of fairy tales published in France in 1697, containing the first written version of “Little Red Riding Hood.” It was sitting on a stanchion, protected in a Plexiglas cube, not just something of value but palpable evidence of one of the better known villains of children’s literature.

It is curious to find the wolf as a character in children’s literature, for all wolves in literature are the creations of adult minds, that is, of adult fears, adult fantasies, adult allegories, and adult perversions. So the tendency to look on animal stories as simplistic is misleading. The wolf of Aesopian fable has changed little in twenty-five hundred years, but he is not just an unchanging symbol of bad behavior. He stands in the child’s mind for something very real. It is Aesop’s wolf, not Science’s wolf—a base, not very intelligent creature, of ravenous appetite, gullible, impudent, and morally corrupt—that generations of schoolchildren are most familiar with. And it was through the fables of Aesop, Avianus, Babrius, and Phaedrus that many children of other centuries first encountered a moral universe beguiling in its simplicity and seemingly rich in worldly wisdom. Some children weaned on fable never inquired deeper into the animals than the stories led them, and so went through life believing the wolf evil, the fox sly, the bee industrious, and the ass foolish.

As adults, too, we often lump the wolves of all children’s literature together. But the wolf of fable is really rather different from the wolf of the fairy tale. In fables—short, didactic, usually plotless aphorisms—the wolf’s poor nature is ascribed to his having been born a wolf and it is possible to feel some sympathy for his predicament. Wolves are not hated in fables, the emotions elicited from the reader are not strong, the wolf is not hell-driven and malicious. He is not a complex beast at all. The wolf of fairy tale and folktale is a much fuller character, capable of diabolical evil and also, occasionally, of warmth and unflinching devotion. If the wolf of fable represents the perceptions of the conscious mind, the wolf of fairy tale represents the unconscious and becomes, as so frequently of late in analyses of “Little Red Riding Hood,” a vehicle for sustaining the fantasies of the sexual unconscious.

The fable draws its morals and aphorisms from the easily observed world of nature, which is one reason its morals seem so apt. Fairy tales, oh the other hand, proceed from abstractions and engage us at a deeper level. The fable is abrupt and cynical; the fairy tale is kinder, I think. It ministers to our anxious impulses and soothes us, despite occasional psychological darkness.

The wolf of fable and literature, then, should not be taken solely for the entertainment he affords to children. From Aesop to the novels of Jack London, he has laid claim to a far greater part of our imagination.

Now the hungry lion roars,

And the wolf behowls the moon.

A MIDSUMMER-NIGHT’S DREAM v.1.379

You may as well use question with the wolf.

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE iv.1.73

They have scared away two of my best sheep,

which I fear the wolf will sooner find

than the master.

A WINTER’S TALE iii.3.67

Since all is well, keep it so: wake not a sleeping wolf.

2 HENRY iv i.2.174

If thou wert the wolf, thy greediness

would afflict thee, and oft thou

shouldst hazard thy life for thy dinner.

TIMON OF ATHENS iv.3.337

He’s mad that trusts in the tameness of a wolf, a horse’s health,

a boy’s love, or a whore’s oath.—

KING LEAR iii.6.20

Scale of dragon, tooth of wolf,

Witches’ mummy.

MACBETH iv.1.22

’Tis like the howling of Irish wolves

against the moon.

AS YOU LIKE IT v.2.162

They will eat like wolves and fight like devils.

HENRY V iii.7.162

And now loud–howling wolves

Arouse the jades

That drag the tragic melancholy night.

2 HENRY VI iv.i .3

As salt as wolves in pride.

OTHELLO iii.3.404

Thy desires

Are wolvish, bloody, starved, and ravenous.

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE iv. 1.138

—JOHN BARTLETT, A.M.

from A Complete Concordance of Shakespeare

The fabulous literature of the Northern Hemisphere in which the wolf appears is, obviously, enormous. It is tempting at first to peruse such collections for insights into what people knew of wolves at different times and places, but as G. K. Chesterton wrote, in an introduction to Aesop, “The lion must always be stronger than the wolf, just as four is always the double of two … the fable must not allow for what Balzac called ‘the revolt of the sheep.’ ” The wolf character, then, is more or less consistent. What is revealed by collections of fables is the political and social satire of an age, and which figures in history were taken for wolves in their time. Thus a Russian fable by Ivan Krilov, “The Wolf in the Kennel,” which appeared in 1812, has a gray-coated wolf after a man’s sheep, clearly the gray-coated Napoleon who had just invaded Russia.

The wolves met with in fable, however, were not actually stock characters. In the hands of various fabulists they were slightly different, according to the author, his intent, the audience he was writing to, and so on. So the wolf we find in Krilov shows more force and intelligence and is more rapacious. In a dark and excessively didactic collection by the Jewish writer Berekhiah ben Natronai ha-Nakdan, which appeared in the thirteenth century, the wolf is more sinister, more fundamentally wicked. In La Fontaine the wolf has more character and self-awareness than he does in earlier collections. Edward Moore, an eighteenth-century English dramatist, created in his fable “The Wolf, the Sheep, and the Lamb” a consciously evil, murderous beast who bargains with a sheep for her lamb, whom he takes as his bride. The lamb lives in terror as her husband slaughters sheep for his meals. Hunters almost shoot him one day and he accuses his lamb bride of treachery in setting them on his trail, which she has not done. Finally, in a rage he says: “Thou traitress vile, for this thy blood/Shall glut my rage, and dye the wood.”

The fables we call “Aesop” today represent an oral tradition that, like the chapters of the Physiologus, was set down by more than one author. The earliest collection of Aesop we know of is one in iambic verse by the Latin poet Phaedrus. The earliest Aesop in Greek is one from the second century by Babrius, but it shows the effects of his having lived for a while in the Near East. The influence of fable collections from India, called the Fables of Pilpay or Bidpai and taken from the Panchatantra and the Hitopadesa, and stories of the Buddha in animal form from the Jatakas, show up more clearly in Aesopian collections after 1251, when Arabic versions of the Persian were finally translated into Spanish and Hebrew and, later, into Latin and other vernacular languages. (The jackal of these stories was grafted onto the wolf tradition in Aesop.) The fourth-century Roman poet Avianus based his very popular verse collection on Babrius, however, so the Eastern influence in collections of Aesop was fixed rather early, and there is some reason to treat the wolf of fable as therefore universal.

Whether Aesop ever lived at all is a matter of conjecture. He is thought by some to have been a freed slave who lived in Greece about 600 B.C, a man who used his fables to criticize indirectly the injustices of his day. Today few people in the Northern Hemisphere have not heard of him.

WOLF FABLES OF AESOP

THE DOG AND THE WOLF

Discouraged after an unsuccessful day of hunting, a hungry Wolf came on a well-fed Mastiff. He could see that the Dog was having a better time of it than he was and he inquired what the Dog had to do to stay so well fed. “Very little,” said the Dog. “Just drive away beggars, guard the house, show fondness to the master, be submissive to the same rest of the family and you are well fed warmly lodged.”

The Wolf thought this over carefully. He risked his own life almost daily, had to stay out in the worst of weather, and was never assured of his meals. He thought he would try another way of living.

As they were going along together the Wolf saw a place around the Dog’s neck where the hair had worn thin. He asked what this was and the Dog said it was nothing, “just the place where my collar and chain rub.” The Wolf stopped short. “Chain?” he asked. “You mean you are not free to go where you choose?” “Much,” answered the Wolf as he trotted off. “Much.”

THE WOLF AND THE LAMB

One very hot day a Lamb and a Wolf happened to come on a stream at the same moment to quench their thirst. The Wolf was some distance upstream but called out asking to know why the Lamb was muddying the water, making it impossible for him to drink. The Lamb, quite frightened, answered as politely as he could that he could not have muddied the water as he was standing downstream. The Wolf allowed that that might be true. But he claimed he had heard the Lamb was maligning him behind his back. The Lamb answered, “Upon my word, that is a false charge.” This irritated the Wolf extremely and drawing near the Lamb he said, “If it wasn’t you then it was your father. It is all the same anyway!’” And so saying, he killed the Lamb.

THE WOLF AND THE MOUSE

A Wolf stole a sheep and retired to the woods to eat his fill. When he awoke from a nap he saw a Mouse nibbling at the remains. When the surprised Mouse ran off with a scrap, the Wolf jumped up and began screaming, “I’ve been robbed! I’ve been robbed! Stop this thief!”

THE SHEPHERD BOY AND THE WOLF

A Shepherd Boy was watching his flock near the village and was bored. He though it would be great fun to pretend that a Wolf was attacking the sheep, so he cried out Wolf! Wolf! and the villagers came running. He laughed and he laughed when they discovered there was no Wolf. He played the trick again. And then again. Each time the villagers came, only to be fooled. Then one day a Wolf did come and the Boy cried out Wolf! Wolf! But no one answered his cal. They thought he was playing the same games again.

THE WOLF AND THE HUNTER

A hunter killed a goat with his bow and arrow and, throwing the animal over his shoulder, he headed home. On the way he saw a fine boar. He dropped the goat and let fly an arrow at the boar. The shot missed the heart and the boar fatally gored the hunter before he too expired.

A Wolf caught the smell of blood and found his way to the scene. He was beside himself with delight at the sight of all this meat, but he decided to be prudent, to start with the worst of it and finish with the softest, most delectable pieces. The first thing he determined to eat was the bow string. Taking it in his mouth, he began to gnaw. When it snapped the bow shaft sprung and stabbed the Wolf in the belly and he died.

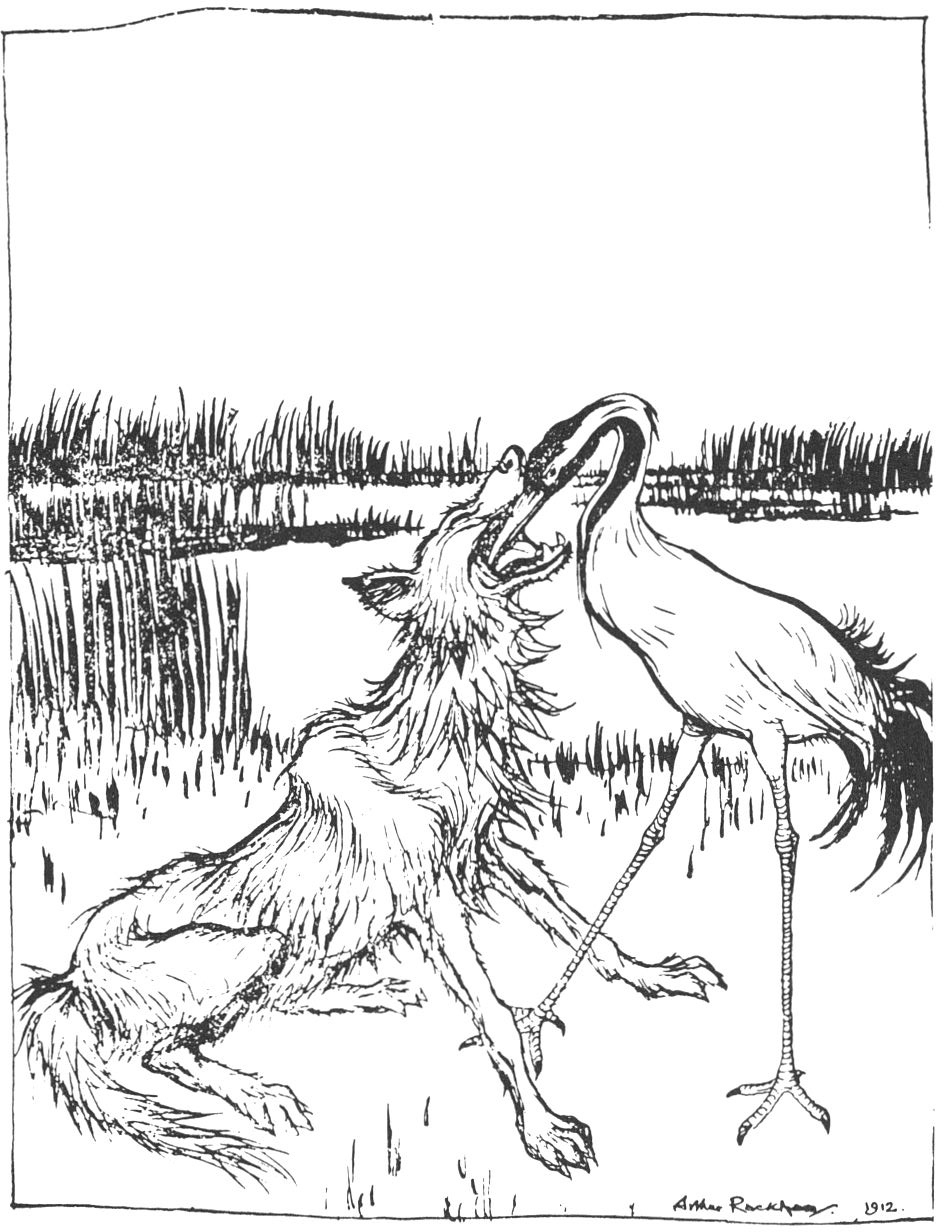

THE WOLF AND THE CRANE

One day a Wolf got a bone stuck in his throat. He was unable to dislodge it and so be went around asking for someone to pull it out. Finally a Crane offered to help. He stuck his long bill down the Wolf’s throat and extracted the bone. When the Crane aske for a reward, the Wolf said, “You are lucky I didn’t bite your head off. That’s all the reward you get.”

THE WOLF HELPS THE DOG

A Dog, grown old in the service to his master and thought to no longer be of any use, was going to be turned out to finish his days alone. One day the Dog met a Wolf to whom he told his plight. The Wolf took pity and between them they devised a plan. The Dog would return to his master’s residence and shortly thereafter the Wolf would attack the sheep fold. The Dog would drive him out and they would feign a ferocious battle, and the Wolf would be driven off. Thus would the Dog be redeemed in the eyes of his master.

Things went just as they had planned. The Dog was welcomed back, praised for his fierce loyalty and bravery, and promised food and a warm hearth until the day he died.

A week later the Wolf returned, asking the Dog for a return of the favor. The Dog was only too delighted to sneak him in to a banquet that evening where, by lying quietly beneath the tables, he could gorge himself royally on scraps from the table. This went very well, nothing suspected, until the Wolf had too much to drink. He began to sing in a loud voice. The master of the house discovered him, and, surmising the ruse, booted both Dog and Wolf out the door.

THE WOLF AND THE SHEPHERDS

One evening a wolf passed near a sheep fold and smelled mutton cooking. He drew close and peered through the bushes. A lamb was roasting over the fire and the shepherds were discussing the good quality of the meat. It if was me that had done this, thought the Wolf, they would be after me with sticks and stones and curses.

Babrius, Avianus, and Phaedrus were the fabulists of record into the Middle Ages, when more free-ranging adaptations and original collections began to appear. Marie de France was writing fables in 1175. William Caxton was publishing Aesop in English for the first time about 1480. Even Leonardo da Vinci was trying his hand at fables. Renaissance scholars began to take a serious interest in fables as literature and, by the beginning of the seventeenth century, hundreds of writers were supporting themselves in part by writing them. Among the more widely circulated works were those of John Gay in England, Gotthold Lessing in Germany, and—by far the best known and most widely imitated—Jean de la Fontaine in France. La Fontaine, interestingly, was writing at a time when French intellectuals were debating the idea set forth by Descartes that animals were beastly machines without souls while men were a separate, mysterious creation. La Fontaine disagreed strongly, which makes what he has to say about the wolf in his fables of more than passing interest. I will return to him in a moment.

In 1818, Thomas Bewick published a collection of Aesop in England that featured his own marvelous woodcuts—his wolves have stunning, huge eyes and enormous feet—and Bewick’s caricature of the wolf can serve as an example of the Aesopian character.

In spite of living in more enlightened times, Bewick wrote out of a tradition that was very strongly of the school of nature, not nurture, as befits the wolf of fable. His wolf was innately evil, irreconcilably and fundamentally corrupt, and not very intelligent. Interestingly, what passes for cleverness in Bewick’s fox is dishonesty in his wolf; and what for the fox is craft is for the wolf cheating. In the morals he appended to the tales, Bewick railed against ingratitude, against the lack of vigilance that lets despots come to power, against gullibility, and against impudence. The wolf serves him primarily as a symbol of impudence and corrupt power—despotism without a conscience. So, in “The Wolf and the Lamb,” he puts the blame for such brutishness to blood, writing in his moral that “men of wolfish disposition and envious and rapacious tempers cannot bear to see honest industry raise its head.” Which is one reason (in the story) why wolves kill lambs. It is their nature. At another point Bewick says the same of people, writing that certain groups, like wolves, have “blood tinctured with hereditary, habitual villainy and their nature leavened with evil.” (On the other hand, in “The Dog and the Wolf,” Bewick’s personal aversion to tyranny and enslavement did force him to give us a noble wolf. He writes there of the “true greatness of soul” that the wolf displays.)

Ivan Krilov, a contemporary of Bewick, was the greatest of the Russian fabulists. There is a statue of him in the Summer Garden in Leningrad which is as famous as that of Hans Christian Andersen in New York’s Central Park. Krilov’s wolves, mostly because Krilov was a masterful storyteller, are among the richest in fable, much more vigorous and frightening than the wolves of European fable; it is tempting to conclude that he either drew them from or contributed to the terrible Russian angst over visions of wolf packs in howling pursuit of sleighs on lonely winter nights. But Krilov had a sense of humor. One of my favorite fables is “The Wolf in the Dust.” A wolf anxious to steal a sheep from a flock approaches the animals from downwind under a cover of dust kicked up by the sheep. “Hey,” says the sheepdog with the flock, when he sees the wolf, “there’s no use your wandering around in the dust like that, it’s no good for your eyes.”

“I’ve got bad eyes anyway,” yells back the wolf over the noise of the sheep drive. “But they say dust kicked up by sheep is an excellent cure for it. That’s why I’m down here.”

Jean de la Fontaine grew up in Château-Thierry and was familiar with animals and the world of nature before he began writing. His fables were well-crafted poems, highly satirical and much copied. The literary critics of his time disparaged the fable as a literary form, saying its subject matter was far too prosaic to warrant poetic treatment. La Fontaine disagreed; eventually he was admitted to the French Academy. The bickering in Parisian salons over the merit of La Fontaine’s fables—their form, their morals, their satirical targets—precipitated discussion of one of the most hotly debated issues of the day: the nature of animals and their place in the universe.

By this time the pseudoscientific view of the bestiaries was waning and the science of natural history, benefitting from Francis Bacon’s cry for a scientific method, was on the rise. Hobbes, who wrote in England but spent much of his time in France, was saying that man was little more than a cog to be politically manipulated, a little machine. René Descartes was delineating animals as “beast machines,” creatures without souls and distinct from man. Rationalists of the time were creating a predictable and lifeless universe.

The idea of Cartesian dualism was one of the most pervasive themes of the seventeenth century, and its reverberations in zoology today are practically as strong as they were in Paris in the 1640s. It held that if an animal has no soul—if an animal is only a machine—then our approach to forms of life other than ourselves can be irresponsible and mechanistic. It was precisely this view that came to dominate the biological sciences and to give men who were otherwise much admired, like Audubon, the ethical space to shoot fifty or a hundred birds just to make a single, accurate drawing. The mechanistic approach to wildlife, further, led biologists to a tragic and myopic conclusion: that animals can be “contained,” that they can be disassembled, described, reassembled, and put back on the shelf. This is an idea that is only now beginning to disappear in zoology.

La Fontaine disagreed violently with Descartes. He believed that animals not only had souls but were capable of rational thought. Montaigne, in a famous essay called “In Defense of Raymond Sebond,” had written with penetrating skepticism about the dogmatic assumptions of this time. One of the evils he attacked most vigorously was the complacency with which scientists like Descartes approached animals. Montaigne argued against the compulsive desire to do away with something by describing it, and he perceived correctly that if you took the mystery out of animals they became nothing more than curiosities. He thought such behavior not only stupid but pathetically arrogant.

But these were isolated voices.

The fable enjoyed a renaissance in the century after La Fontaine’s death before—a limited form to begin with—it exhausted itself as a form of social satire. It was replaced by longer beast epics like Gulliver’s Travels and the stories of Reynard and Isengrim, which had enjoyed wide circulation since the fourteenth century.

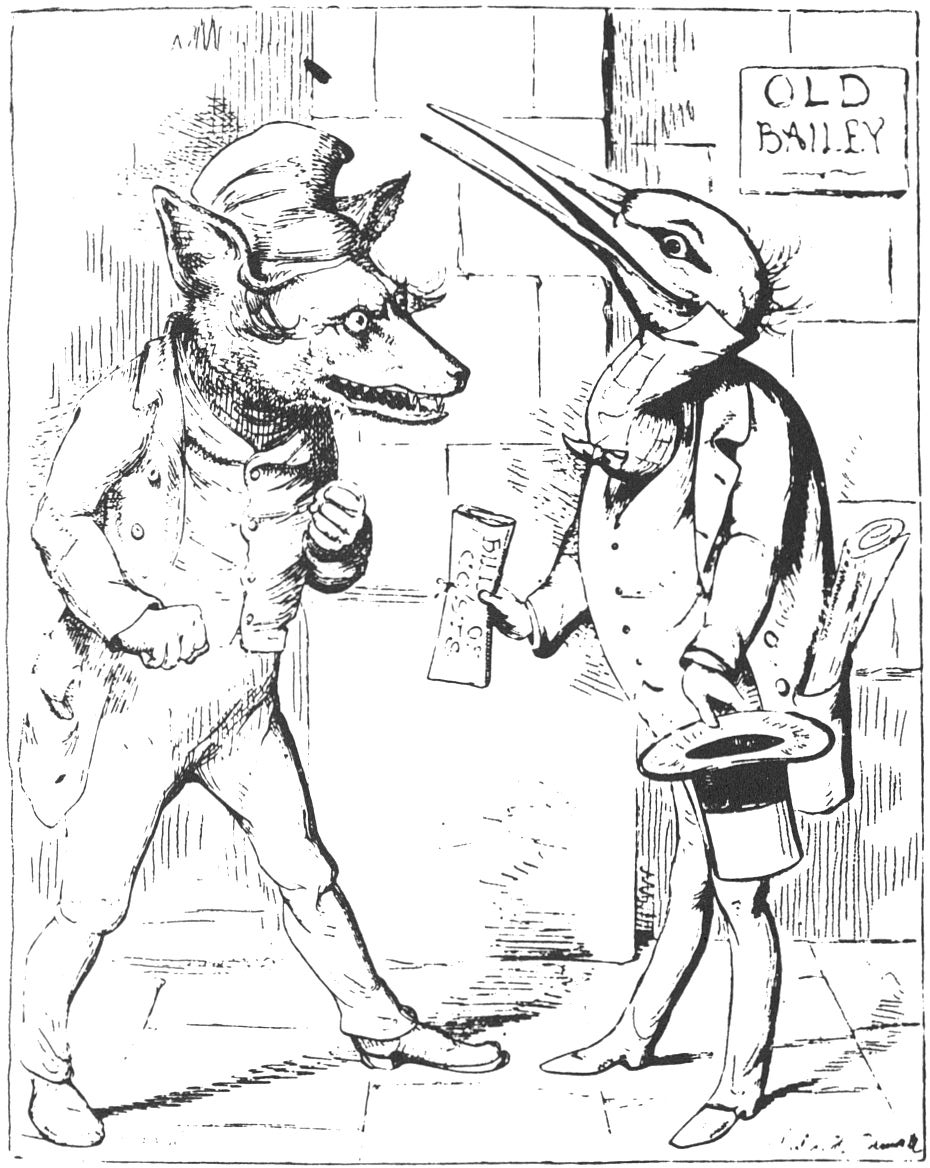

Ysengrimus, a Latin poem of some sixty-six hundred lines, was written in about 1150 by Nivordus of Ghent in Belgium. It was the first literary recording of what by then was a growing oral tradition, stories based on the long-standing feud between Isengrim the wolf, who stood for the lower nobles, and Reynard the fox, a peasant hero. The French Roman de Renart was the product of several thirteenth-century authors and was immediately popular. Reynard’s witty insults and subterfuge and his cavalier nose-thumbing delighted people who were oppressed. His scathing castigation of wealthy clergy and dull-witted nobility, of unpopular monarchs and political and ecclesiastical abuses, brought howls of approval. The story cycle usually began with Reynard’s summons to the court of the king, a lion, to answer charges made against him by Isengrim and others. Reynard defends himself with devious wit and well-placed flatteries. When he has charmed and ingratiated himself with everyone but Isengrim, he volunteers for some adventure to prove his innocence. Off he goes and we subsequently see more of his guile and much of his cruelty. Isengrim is frequently killed in these stories.

Isengrim is forever Reynard’s fool, but the tales have an odd flavor to them today. Isengrim, for all that he is duped, basically tells the truth and tries to lead a moral life. He is also loyal. Reynard is guileful and arrogant, utterly without human warmth, amoral and violent. He gets away with it all in the beginning but in later versions he is punished for his treachery. In The Most Pleasant and Delightful History of Reynard the Fox: The Second Part (1681), wit and comedy give way to brutality and evil, and in the end Reynard is killed along with Isengrim. And in The Shifts of Reynardine, the Son of Reynard the Fox (1684), Reynardine is hung for his evil-doing.

The brief glimpses we catch in the Reynard stories of a wolf with whom we can sympathize recall the heroic werewolf in William of Parlerne and the sympathetic wolves that surface occasionally in folktales, usually as guides, often of children. They show warmth, compassion, and self-sacrifice, contradicting the ghoulish image of the ravening beast.

There were single stories of the wolf and the fox that in time became detached from the Reynard cycle, as well as original creations, so that today there are a large number of fox and wolf stories. In most of them Fox outwits Wolf by getting him to do something foolish, like sticking his tail in a hole in the river ice to catch fish, only to have it freeze there and break off.

The wolf of ethnic folktale is more varied than the wolf of fable and the Reynard stories. In the collections of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm he seems one-dimensional and predictable, but in other collections he is articulate, sagacious, vicious, silly, and endearing by turns. Often, as in a collection of Georgian (Russian) folktales called Yes and No Stories, the wolf is treated miserably by ingrates but nevertheless continues to help them. In a famous Russian story, “The Firebird,” the wolf helps the king’s youngest son find a firebird that has stolen his father’s golden apples. He secures a princess and a fabulous horse for the boy and protects him from his brothers, who want to kill him. Through it all the boy causes one problem after another, but the wolf stays by him.

The other side of the coin is the wolf who is himself helped but then turns on his helper, as in the fable “The Wolf and the Crane.” In a Chinese story called “The Wolf of Chungshan Mountain,” a scholar meets a wolf being pursued by hunters. He kindly offers him a hiding place in his book-bag. When the hunters are gone, he lets the wolf out. The wolf promptly declares his intention to eat the man. The scholar objects and they agree to have the matter debated by the first stranger they meet. The first stranger manages to get the wolf to crawl back in the bookbag by insisting on a complete reenactment of the scene. The stranger then clubs the wolf to death, praises the scholar for his compassion, and remonstrates with him for his foolishness. In other versions the wolf and his benefactor meet three strangers, each of whom says, yes, it is true, favors are soon forgotten in this world—and the wolf eats his erstwhile friend.

Wolf and dog stories form a genre all their own. Classic among them is the ancient Welsh tale of Gelert, a huge hound. Prince Llewelyn leaves Gelert to guard his infant son while he goes off hunting. A wolf creeps into the castle and a desperate struggle ensues, during which the infant’s cradle is overturned. Gelert finally kills the wolf and falls down exhausted. When Llewelyn returns and sees the upended crib and Gelert smeared with blood, he is gripped with rage and drives the dog through with his spear. Only when he turns the crib over does he find his son asleep and see the dead wolf.

Observations on the hypocrisy of men and stories of wolves bent on realistic accommodation with man present us with a sympathetic character. In “The Old Wolf in Seven Fables,” an aging wolf visits the shepherds around him, knowing his days are numbered. He asks the first one for enough sheep to satisfy his hunger in exchange for not terrorizing the flocks and killing more than he needs. No, says the shepherd. He asks the second one for six sheep a year. No. He asks the next for one sheep a year, and is accused of plotting and sent off. To a fourth he offers to act as watchdog against other wolves, to a fifth he promises to eat only sheep that die of natural causes, and to a sixth that he will bequeath him his wolfskin. Finally, spurned by them all, he turns around and wreaks havoc on the flocks of every one.

Many folktales stress the wolf’s gullibility. In “The Wolf’s Breakfast,” a wolf has a dream of a fantastic breakfast and awakens famished. Intent on making it come true, the hungry wolf faces goats, swine, a cock, a goose, a mare and her foal, and a ram. He demands with foolish straightforwardness the life of each in turn, and each engages him in some diverting task long enough to escape. Cursing his endless stupidity he cries aloud for someone to chop off his tail as punishment. A huntsman, conveniently near, obliges. Thus we are cautioned not to put too much faith in dreams.

In a class almost by itself is Serge Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, a symphonic fairy tale in which the young Peter and a small bird capture a wolf who has eaten their friend the duck. When hunters on the wolf’s trail arrive, Peter asks them to spare the wolf’s life and take him to a zoo.

In an eerie, dreamlike native American story from the Pacific Northwest coast a boy named Sheem becomes a wolf. Abandoned by his brother and sister after the death of their parents, Sheem takes to following wolves in order to eat what they leave. The wolves feel kindly toward him and allow him to stay close. One afternoon his brother is fishing on a lake when he hears a child weeping. Paddling toward shore he recognizes Sheem, who now looks a little like the wolves. The young boy cries out to him, “My brother! My fate is near! My woes are ended! I shall be changed!” and so saying he becomes even more wolflike. The brother beaches the canoe and chases after Sheem, trying to gather him in his arms, crying in anguish: “Nee sheema! Nee sheema! My little brother! My little brother!” But the boy eludes his grasp, alternately howling and calling out the names of his brother and sister as he runs. Soon he is a wolf completely and he bounds away.

Before a wolf was brought into their classroom, a group of grade-school children were asked to draw pictures of wolves. The wolves in the pictures all had enormous fangs. The wolf was brought in, and the person with him began speaking about wolves. The children were awed by the animal. When the wolf left, the teacher asked the children to do another drawing. The new drawings had no large fangs. They all had enormous feet.

The people of Lithuania tell of a wolf who promised to give up killing animals and to lead a holy life. Things went well until one day the wolf was going down the road and a gander came flapping up to him. He wrung its neck. “Geese shouldn’t hiss at saints,” he said.

The stories of “Little Red Riding Hood,” “The Three Little Pigs,” and “The Seven Little Goats” are perhaps the best-known fairy tales in which the wolf plays the role of an ogre. Of these the reader probably only needs to be reminded of the plot for the third: a wolf, uttering secret words he has accidentally overheard and imitating the voice of a mother goat, tries to get into a locked house where there are seven goats. They doubt whether it is their mother and ask the wolf to prove it by showing his white hooves in the window. The wolf raises his flour-dusted paws, the goats are convinced, and they let him in. He eats them all, save the smallest who hides in the grandfather clock. When the mother returns, the little goat tells her what has happened and with the help of a huntsman they track the wolf down. They find him asleep by a stream. The huntsman cuts him open, removes the young goats, stuffs the wolf with rocks, and sews him up. Awakened, the startled wolf jumps in the stream and drowns.

The sexual undercurrent in “Little Red Riding Hood” has been a topic of frequent allusion among psychologists for years, though Charles Perrault’s original version presents an unresolved problem and is more a cautionary tale with a moral than a fairy tale. In Perrault’s version the wolf eats Red Riding Hood and that’s that. In later versions Red Riding Hood is rescued in various ways. According to a short history of the story written by Iona and Peter Opie, in Madame de Chatelain’s Merry Tales for Little Folk (1868) a wasp stings the wolf, whose bark alerts a tomtit, who warns a huntsman, who shoots an arrow that kills the wolf. In an 1840s version, Red Riding Hood screams and her father rushes in to save her. In a nineteenth-century version popular in Brittany the wolf puts grandmother’s blood in a bottle, which he gives to Red Riding Hood to drink before killing her. In the Brothers Grimm the wolf eats Red Riding Hood and falls asleep. His snores bring huntsmen, who open his belly to get Red Riding Hood and her grandmother out and then fill it with rocks, recalling again the wolf’s antipathy for stones. This is the version, I believe, that appears in a book with a delightful title, published in 1760 in England: The Top Book of All, For Little Misters and Misses.

James Thurber, in a 1930s version, has Red Riding Hood shooting the wolf with a pistol she had hidden in her basket. Writes Thurber, “Moral: It’s not so easy to fool little girls nowadays as it used to be.”

Bruno Bettelheim, in The Uses of Enchantment, analyzes “Red Riding Hood” or, as the story is known in Grimm, “Little Red Cap,” in sexual terms. A prepubescent girl announcing her sexual availability with her red cap is approached by a seducer, who entices her to forsake what Bettelheim calls the reality principle (staying on the path to grandmother’s) for the pleasure principle (going off to pick flowers). Red Cap picks flowers until she can’t hold any more and then suddenly remembers her errand. Thus we see her ambivalence about whether to live by the reality principle or the pleasure principle. A similar scene occurs at grandmother’s when she gets undressed and gets into bed with the wolf. She doesn’t know whether to stay and resolve the oedipal conflict or bolt from the bed. The male nature, writes Bettelheim, is what Red Riding Hood is trying to cope with, and for her it is split into two opposite forms: the dangerous seducer and the rescuing father figure.

Red Riding Hood.

“It is as if Little Red Cap is trying to understand the contradictory nature of the male by experiencing all aspects of his personality: the selfish, asocial, violent, potentially destructive tendencies of the id (the wolf); and the unselfish, social, thoughtful and protective propensities of the ego (the hunter).

“Little Red Cap is universally loved because although she is virtuous, she is tempted; and because her fate tells us that trusting everybody’s good intentions which seems so nice, is really leaving oneself open to pitfalls. If there were not something in us that likes the big bad wolf, he would have no power over us. Therefore, it is important to understand his nature, but even more important to learn what makes him attractive to us. Appealing as naïveté is, it is dangerous to remain naïve all one’s life.”

Bettelheim goes on to say that what appeals in the wolf is his capacity to provide simultaneously tremendous excitement and great anxiety, the essence of the sexual act in the mind of a child for Bettelheim.

Erich Fromm has suggested that the wolf’s eating Red Riding Hood represents both a hostile feminine view of the destructive nature of the sexual act, and a male desire to usurp the female role by having living beings inside it.

I think “Little Red Riding Hood” might be examined as an extended metaphor on another level. Like “The Three Little Pigs” and “The Seven Little Goats,” this is a violent story. And the violence done to the wolf is socially acceptable. If one imagined cattlemen and woolgrowers as Red Riding Hood’s avenging father, it would be easy to see sheep and cows as their little girls and the wolf as the lurking rapist. What makes this suggestion less than facetious is that the sort of outrage and the promise of violence stockmen manifested when they found a wolf-killed sheep is uncommonly like that manifested by men on hearing that a neighbor’s child has been raped by an itinerant laborer.

Making Freudian connections between sex and violence in wolf terms can quickly land one in an analytical morass. The wolf is called female destructive and male destructive. He is called a threat to the male ego as well as a projection of the male ego. He is suavely seductive; he is brutally violent. The reader can do as well as I here. Our historically ambivalent vision of the wolf is, again, very evident. An odd thought that remains with all these stories is that as adults it is often only these violent tales of hedonistic, ravenous wolves that we most easily recall. Why that should be I do not know. Perhaps these were the stories our parents and teachers emphasized. In any case it seems disconcertingly clear that this is the wolf we are preoccupied with.

In an essay entitled “The Occurrence in Dreams of Material from Fairy Tales,” Sigmund Freud recounts the childhood dream of a patient he calls the Wolf-man. The child was born, curiously, on Christmas Eve, 1886, in western Russia to an upper-middle-class family. He grew up maladjusted, and in psychoanalysis Freud traced his infantile neurosis through a boyhood dream that, Freud felt, derived in part from the child’s having been frightened by the wolves in Red Riding Hood and other children’s stories.

In the dream the boy is lying in bed at night. He is looking out over the foot of his bed through casement windows at a row of walnut trees. It is winter and the old trees are without leaves, stark against the snow. Suddenly the windows fly open and there sitting in a tree are six or seven wolves. They are white, with bushy tails, their ears cocked forward as though they were listening for something.

The boy awakes screaming.

Freud’s analysis has not much to do with wolves, but the boy’s dream is surely as eerie, as surreal, a vision of wolves as exists in any fairy tale.

The place of wolves in literature would not be complete without at least an allusion to the body of fiction that bears on wolfish themes, though the basis for much of it will by now be clear. There are the Jungle Stories of Rudyard Kipling, perhaps best known, featuring Mowgli, the boy adopted by wolves. Frank Norris, a turn-of-the-century exponent of naturalism, developed “lycanthropy mathesis” as a state of moral degeneration and severe depression in Vandover and the Brute. Werewolfry was a minor but staple theme of popular literature in America until the thirties, and I have already mentioned Guy Endore’s The Werewolf of Paris. G. W. M. Reynolds wrote a Victorian thriller called Wagner the Wehrwolf that was wildly popular in magazine installments in 1846/47. Guy de Maupassant in a strange and crude short story called “The Wolf” features two pathologically insane brothers in hot pursuit of a wolf. One brother has been struck by a limb during the chase and his head crushed. His dead body is strapped crosswise in his own saddle. When the wolf finally turns to fight, the live brother props the dead one up in some rocks to watch. Then, hysterical with power, he throws away his weapon and strangles the wolf. H. H. Munro (Saki) wrote a werewolf story of charm and humor in “Gabriel-Ernest,” featuring a sixteen-year-old nature boy; and his “The She-Wolf” is an amusing drawing-room farce in which a stuffy matron is apparently changed into a wolf. There is a maniac in John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi who believes himself a mad wolf and a lycanthropic character of Gothic horror appears in Charles Robert Maturin’s The Albigenses. The English novelist Algernon Blackwood wrote a number of bloody werewolf stories.

Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Willa Cather’s My Antonia contain archetypal wolf scenes: in the former it is a fantastic battle in the Pyrenees, in the latter a reminiscence about a bride and groom thrown to the wolves one wintry night by the driver of a pursued sleigh. This is the most oft-repeated wolf scene in literature, its apotheosis being the scene in Robert Browning’s “Ivan Ivanovitch” in Dramatic Idylls, where the mother throws her children to the wolves.

The American poet Hamlin Garland captured some of the bitterness of life in the Upper Midwest in the nineteenth century and some of the hatred directed at wolves by those people when he wrote:

His eyes are eager, his teeth are keen

As he slips at night through the brush like a snake

Crouching and cringing, straight into the wind

To leap with a grin on the fawn in the break.

And in a poem called “The Wolves,” another American poet, Galway Kinnell, speaks of buffalo hunters and wolves in such a way as to leave the hunters saddled with the bestial imagery usually put to the wolf. D. H. Lawrence was very much taken with the animal life of the American Southwest. In “Autumn at Taos” he compares the ash gray sage of the desert mesas to a wolf’s back, describing it as a kind of land fur. In “The Red Wolf,” a pueblo seer calls Lawrence a thin red wolf of a paleface, recalling Northern Plains Indian allusions to the East, the direction from which Lawrence has come, as the place of the wolf and the color red. Robinson Jeffers penned my favorite two lines about the wolf:

What but the wolf’s tooth whittled so fine

The fleet limbs of the antelope.

I have indicated already that the oral literature of native Americans was rich with wolf stories. The Indian wolf, of course, was not the European wolf, though the familiar theme of shapeshifting—which nineteenth-century Europeans frequently took for werewolfry when they heard these Indian stories—is common. George Bird Grinnell recorded many wolf stories among the Blackfeet, Pawnee, and Cheyenne. One of the most haunting is “Black Wolf and His Fathers,” in his By Cheyenne Campfires. A man left to die in a pit is rescued by two wolves—one white, one rabid. During a long journey to the Place of the Wolves, the white wolf must keep constant guard so that the rabid wolf won’t attack the man. With the white wolf’s help, the man is later adopted by the wolves. When he returns to his tribe, he kills the two women who left him to die in the pit and offers their bodies to the wolves. Grinnell also has a similar story in Blackfoot Lodge Tales entitled “The Wolf-man.”

But if there is one writer whose name must be linked with the wolf it is of course Jack London. He was obsessed by them. Call of the Wild and White Fang are widely known. In the former a dog regains its “wolfish heritage” in Alaska, and in the latter a wolf is tamed. The character of Wolf Larsen in The Sea-Wolf is probably a projection of London’s own personality. His first story collection was entitled The Son of the Wolf.

London named his dream house, never completed, Wolf House, and delighted in being called Wolf, the name his perhaps homosexual friend George Sterling gave him. (Literary allusions to homosexual lovers as “wolves after lambs” are not rare. Plato, in Phaedrus, writes, “The eager lover aspires to the boy just as the wolf desires the tender lamb.”) London was accused of being homosexual because of his aggressive displays of drinking and forcing himself on women, behavior that he thought proved his masculinity. In a poignant scene a month before he died, London asked his wife to have a watch he had given her inscribed “Mate from Wolf,” and lamented that she did not call him more often by that name.

London’s novels show a preoccupation with “the brute nature” in man, which he symbolized in the wolf. In The Sea-Wolf Larsen’s internal war is between his brutish and civilized natures, though the idea of the brute as London presents it is admirable. But it is, ultimately, a neurotic fixation with machismo that has as little to do with wolves as the drinking, whoring, and fighting side of man’s brute nature. London, one of the most frustrated and perhaps tragic figures in American literature, nevertheless struck responsive chords with his themes. Few twentieth-century American authors have been as widely translated and appreciated outside America.

Even so swift and cursory a glance at wolves in literature as this reveals that—except for a few stories here and there where a writer wasn’t bound by the conventions of fable or the happy endings of fairy tales—the role of the wolf is fairly predictable. London’s wolves and wolfish men seem more serious-minded and are more engaging because he was writing about a facet of human nature—the bestial side, the wolf side of man—and was not content to let the wolf stand simply as a stock symbol.

The possibility has yet to be realized of a synthesis between the benevolent wolf of many native American stories and the malcontented wolf of most European fairy tales. At present we seem incapable of such a creation, unable to write about a whole wolf because, for most of us, animals are still either two-dimensional symbols or simply inconsequential, suitable only for children’s stories where good and evil are clearly separated.

Were we to perceive such a synthesis, it would signal a radical change in man. For it would mean that he had finally quit his preoccupation with himself and begun to contemplate a universe in which he was not central. The terror inherent in such a prospect is, of course, greater than that in any wolf he has ever written about. But equally vast is the possibility for heroism, humility, tragedy, and the other virtues of literature.