THE CITY OF LANGUAGE(S)

Language is distinctive to human beings, not to particular cities. But which language matters when and where can be the cause of social conflict in multilingual settings. How do we feel when our mother tongue is threatened with extinction? And when other languages offer more economic opportunities? Only when such issues become matters of public debate are we really made aware of the value of language, both in the monetary sense and in the psychological sense of feeling at home in the world. And if there’s one thing we can say about Montreal, it’s that people care about their language(s). The city has been the center of conflicts over language ever since the French explorer Jacques Cartier mistakenly stumbled on the almond-shaped island in 1535 (he was looking for China, and the rapids that he thought prevented him from reaching its wealthy markets have been named “Lachine” in honor of his quest). It’s an ongoing conflict, but I think this story can be told in ways that foretell a somewhat happy ending for the Francophone and Anglophone communities. I spent nearly half my life there—from 1964 to 1986—just when things were most exciting, or turbulent, depending on one’s perspective.

The chapter opens with a discussion of the linguistic conflicts between Canada’s First Nations and the European settlers and merchants. The next section focuses on the “conquest” of the Francophone by the Anglophone community, followed by a section on the Francophone “reconquest.” The chapter ends with an argument that a broader and more inclusive form of civicism has emerged from the wreckage of the language wars, along with a reminder that one attachment—to the Montreal Canadiens hockey team—has long transcended linguistic boundaries.

WHICH SOLITUDES?

I grew up thinking that Montreal was composed of two long-established linguistic communities: the French and the English. In school, I was taught which Europeans had “discovered” which parts of North America, as though the people already there didn’t count. In fact, I didn’t really question my prejudices until I met my first girlfriend, Kathy, who was born in Canada’s far north to an Inuit mother and a white father who abandoned her at an early age.

The historian Marcel Trudel tells the story of Cartier’s encounter with what we now call Canada’s First Nations.1 At the time, French was the language of elites in Europe, and Cartier and his fellow explorers spoke only that language, without any felt need to learn others. Thus, when he first encountered members of the Micmac nation, “conversation” could only take the form of hand and finger movements. When the Micmacs, cod fishermen who were keen to do business with another client, approached Cartier’s ship, the French explorer panicked and resorted to a less ambiguous mode of communication: he fired warning shots over their heads. A few days later, he encountered members of the Iroquois nation and again resorted to ineffective hand signals. Frustrated, Carter decided to embark on the first experiment with bilingualism in Quebec’s history: he captured two Iroquois and brought them to France, where they learned some French and served as interpreters during Cartier’s next trip. To Cartier’s consternation, the two interpreters also learned to play the game of commerce and informed fellow Iroquois that they should ask for more in return when bartering for items.

Europe withdrew from the Saint Lawrence River basin for a half century or so, and the next French adventurer, Samuel Champlain, discovered to his dismay that the Iroquois community in Montreal—Hochelega, as it was then known—had moved elsewhere and his hard-earned Iroquois vocabulary was useless for communicating with the Montagnais and Algonquin peoples that had replaced them. The linguistic misunderstandings had tragic consequences for Champlain’s men—eighteen out of twenty-six died from scurvy because they did not have the vocabulary necessary to procure the Iroquois herbal remedy that had saved Cartier and his men.

This time the French became more serious about language learning. They decided to immerse themselves in the language communities of the native peoples as well as try to teach French to the locals. In 1610, a young Frenchman named Étienne Brûlé spent the winter with the Algonquins and was perhaps the first case of what anthropologists call “going native”: he returned to France dressed like an Algonquin. In 1620, a young Montaignais named Patetchouan was sent to France, where he learned both French and Latin. But when he was brought back to Canada after five years, the French discovered that he had lost his native tongue and could not serve as interpreter as they had hoped.

French missionaries made more serious efforts to learn and translate the languages of First Nations, and in 1632 they published a 132-page Huron dictionary, the first of its kind for a language from North America. Although the Huron community was not large, their language was the language of commerce in the Great Lakes region and Europeans were keen to learn it. But the Hurons were defeated by the Iroquois fifteen years later, and the Huron language ceased to have “international” status.

For the seventeenth and much of the eighteenth centuries, the experience of bilingualism meant that the French had to learn the languages of First Nations rather than the other way around. Why is that? Again, mainly for commercial reasons: the First Nations controlled commerce and the French were in a position of numerical inferiority. More surprising, the indigenous languages were also used by the French and the English to communicate among themselves! They hadn’t learned each other’s languages in Europe, and the native languages used in North America were the only common ones. That all changed when the French were defeated by the English in the war of 1759, in what Francophone Québécois refer to as the “Conquest.” The English colonialists established themselves as the dominant power and English became the primary language of trade. The First Nations were largely marginalized throughout subsequent Quebec history, and Montreal became the focal point for conflicts over two European languages: French and English. The two busiest bridges in Montreal were named after the French explorers Cartier and Champlain, and most Montrealers would be hard pressed to come up with anything that was named after the First Nations.

TWO SOLITUDES

As a kid, I attended a French school for grades one and two in Outremont, an almost exclusively Francophone neighborhood. We moved to an Anglophone district named Notre-Dame-de-Grâce (NDG), and I attended English language schools after that. I had separate sets of friends, and they never mixed. Perhaps the only thing my friends had in common was that they played hockey after school in publicly subsidized neighborhood ice rinks that were often de facto segregated by language. And my friends watched the Montreal Canadiens’ hockey games on TV: in French for the Francophones, English for the Anglophones.

Writing in 1945, Hugh MacLennan famously declared that Anglophones and Francophones in Montreal were “two solitudes” that had decided “the best way to coexist was to ignore the existence of one another.”2 The city has been historically divided between the Anglophone west and the Francophone east for well over two centuries: a declaration in 1792 stipulated that the city would be divided into two districts, with St. Lawrence Boulevard as the line of demarcation, and still today the east-west split largely divides along linguistic lines. One feature of city life is that its denizens often define themselves against other cities, and here too there has been a historic division, with Quebec City as the main historic rival for Montreal’s Francophones3 and Toronto for the Anglophones.

At first, the linguistic division was not so politically explosive. When Montreal was conquered by the British in 1760, it was a fur-trading settlement of several thousand French colonialists. The British army was followed by British merchants, who went on to control two-thirds of the fur trade by 1820. The names of those merchants—McGill, Molson, Redpath, and McTavish—still adorn streets signs and key institutions in the western part of Montreal.4

Powered by its economy, Montreal became a magnet for English-speaking immigrants from the British Isles in the early nineteenth century, and by 1855 more than half of the city’s residents were of British origin. In the 1860s, however, the city’s linguistic composition shifted for good and Montreal became a French city in demographic terms. Montreal’s industrial economy drew thousands of Francophones from the impoverished countryside, and the population of the city reached one million by 1931, more than 60 percent of which was Francophone.

But the Anglophones continued to dominate the economy. In 1900, the English-speaking residents of the wealthy neighborhood known as Westmount were estimated to control 70 percent of all Canadian wealth: in the words of the humorist Stephen Leacock, they “enjoyed a prestige in that era that not even the rich deserved.”5 In 1961, the concentration of Anglophones in the city’s best jobs helped produce a 51 percent wage gap between French- and English-speaking Montrealers. Through 1970, nearly 80 percent of predominantly Anglophone census tracts on Montreal Island—all located on the western part of the island—had annual family incomes higher than the metropolitan median. Anybody who wanted to succeed economically above the middle-management level in the private sector had to speak English, which put Francophones at a considerable disadvantage.

Of course, not all Anglophones were wealthy. In the 1840s, Irish immigrants fleeing the Potato Famine were located in poor neighborhoods and arguably were worse off than poor Francophones, who had the protection of the Catholic Church. Nor were the Anglophones always unified among themselves prior to the language wars of the 1960s: for example, British Protestants openly discriminated against Jews in educational policy. But English was considered the language of upward mobility, and that’s what the new immigrants learned. Although Montreal was predominantly French demographically, its linguistic character, as Marc Levine puts it, “was undeniably English. Montreal was the urban center of English Canada where corporate boardrooms functioned in English, the best neighborhoods were inhabited by English-speakers, downtown was festooned with billboards and commercial signs in English, and where the language of the city’s minority—English—exerted a greater assimilationist pull than the language of the majority.”6 Prior to the 1960s, bilingualism was largely one-way, with ambitious Francophones learning English and working in an English environment, even if it meant cultural alienation. For their part, Anglophone Montrealers could live and work in English just as in any other city in Canada or the United States. In one telling statistic from 1961, unilingual Anglophones had a higher average income than bilingual and unilingual Francophones, and virtually the same average income as bilingual Anglophones.

It’s worth asking why Francophones largely tolerated such arrangements prior to what became known as the “Quiet Revolution” in the 1960s. One reason is that the British rulers rapidly learned the virtues of noninterference. When the British conquered Montreal in 1760, they implemented an aggressive policy of assimilation, including outlawing Catholicism, the religion of Canadiens, and barred Catholics—that is, Canadiens—from holding colonial office. But British policy soon became more accommodationist and culturally tolerant out of fear that French Canada might become a fourteenth rebellious colony. In the 1770s, the British worked out accommodations with the French seigneurial and clerical elite and French was used as the language of public administration. Two centuries later, Quebec nationalists would worry that the assimilationist pressures of living next to the United States would turn Quebec into another Louisiana, where French language and culture survive merely as folklore and charm to attract tourists, but it is one of the ironies of history that the American Revolution may have had the effect of saving French culture and language in Quebec.

After the Conquest, the British rarely interfered with French language, religion, and schooling. In 1837, Louis-Joseph Papineau (a major street is named after him in east Montreal) led an uprising in Montreal demanding more responsible government from the unelected British rulers. The rebels were crushed and Lord Durham, a known reformer, was appointed governor general to investigate colonial grievances. Although the rebellion had more to do with the unfairness of colonial government than language and culture, Durham described the problems in Lower Canada as “two nations warring in the bosom of a single state.”7 His report (in)famously condemned Canadiens as a “people with no literature and no history” and urged assimilation into “English habits.”8 Almost in response to Lord Durham’s harsh verdict, the next few years were characterized by a flowering of distinctively Canadien literature and accounts of history.9 The project of assimilation was abandoned for good in 1867, when the Canadian Confederation (regarded as the founding of Canada) gave official political and legal status to the French language.

But joy over the “French parliament” in Quebec was short lived as it became clear that the French language was not equal in practice. The language of business and work was still English, bilingualism meant assimilation into English language and culture, and about nine hundred thousand Canadiens left Quebec to try their chances in the United States.10 So why didn’t Francophones in Quebec use the democratic power of the ballot box to push for equal economic opportunities in their own language? Since the 1840s, the political leaders of Canadiens had veto power over policy issues affecting community interests, and after Confederation Francophones ran the provincial political system, but they didn’t use the state to equalize economic opportunities for their linguistic community until the 1960s. An important reason is that Francophone religious leaders clung to a vision of a homogenous and isolated community blessed by God with superior nonmaterialistic values. In his work Histoire du Canada français depuis la Découverte [History of French Canada since the Discovery], the influential theologian/historian Lionel Groulx wrote that what France left in America at the moment of the Conquest was “a population of white peoples, French; nothing like elsewhere in America, of mixed population, half-indigenous…. [O]nly one type of colony was then possible: a colony of a white race…. The rare pleasure of our small Canadiens people, in its crib, was to receive from the Church, regarding God, man, its origin and its destiny, right, justice, and liberty, the highest metaphysic ever attained by the human genius, itself elevated by real faith.”11 Marcel Trudel notes that Canadiens “were inculcated with exalted theses that placed them ahead of other nations: you were chosen, it was repeated to them, to spread the civilization of Christ; different than your neighbors, you are animated with spirituality and not the passion for material goods; you form a human group without mixture, you are a white population, the family in your home is what’s most beautiful in the world; a highly moral society, you respected others’ rights and you accomplished extraordinary deeds.”12 With that sort of education, no wonder Francophone Montrealers didn’t fight too hard for language rights aimed at equalizing economic opportunities. But that all changed when God died in Quebec shortly after Groulx published his book in 1960.13 In the minds of most Francophones, He—God—was replaced by an ideal of a nation where Québécois could be maîtres chez nous (masters in our own house), where they could live as economic equals secure in their own language and culture. But they had to take on the English-speaking economic elites in Montreal to realize that dream.

THE RECONQUEST OF MONTREAL

My mother, a Francophone Catholic, married my father, an Anglophone Jew, in 1962. At the time, it was a radical break with tradition. My parents fought over religion when I was a baby, and I was both circumcised and baptized. But they eventually decided not to promote any religious values in order to avoid conflict—a kind of Rawlsian “overlapping consensus” within the family—and the rest of my upbringing was religion free (other than the occasional prayer with my kind and devout Catholic grandmother, who recently passed away at the age of 101). My sister and I learned two languages—French from our mother and English from our father—before we had to make any conscious effort to learn languages. My mother became politicized and strongly identified with the proindependence forces. My father wrote an article titled “So I Married a Separatist” for a leading Canadian magazine in the late 1960s, at the height of violent conflicts over language in Montreal. My parents separated shortly thereafter, and my sister and I lived with our mother, though we saw our father every Sunday.

In the 1960s, the city’s linguistic climate changed quickly and language became politicized as never before. The upheaval began with what became known as Quebec’s Quiet Revolution: a Montreal-centered challenge by an emergent Francophone “new middle class” to the conservative, agrarian, and religious-based nationalism of the old elites. The challenge to the old Francophone elites was relatively “quiet”; primarily, Canadiens left the farms and towns of rural Quebec for Montreal, and stopped going to church and having many babies. But the challenge to the English-speaking elites was less “quiet.” As Marc Levine puts it, “this ‘Montrealization’ of French Quebec had made the traditional Canadien ideology, in which cultural survival was predicated on the rural isolation of French Catholics and in which Montreal’s English character remained unchallenged, an anachronism. Montreal, not rural Quebec, was now the center of Canadien culture and the place where the future of French in North America would be determined. In this urban setting, English-language influences were infinitely stronger than in the homogenously Francophone parishes of rural Quebec; thus, the continued survival and épanouissement [flowering] of the French language and culture would seem to require confronting the status of the English in Montreal.”14

My mother told me a story about going downtown to shop at Eaton’s and being addressed in English. When my mother spoke French, she was made to feel inferior, even though she was bilingual and the salesperson was a unilingual Anglophone. Still today, she prefers shopping at a neighboring department store (the Bay) that sells more or less the same things. (Not coincidentally, perhaps, Eaton’s has since gone bankrupt.)

With few opportunities in the Anglo-dominated private sector, the secular and upward-striving Francophone class dramatically expanded the role of the provincial government in Quebec. Throughout the 1960s, the Quebec state expanded its functions and replaced the Catholic Church as the most visible presence in provincial life. The provincial government took over from the Church control of social and health-care services, an expanded bureaucracy provided job opportunities for Francophones, and public education was dramatically expanded, including a nine-campus Université du Québec system. The Quebec state also took steps to improve Francophone control of the Quebec economy by setting up an investment fund, a state-run steel mill, and a holding company. The most contentious and linguistically charged action of the provincial government during the Quiet Revolution was the “nationalization” of Hydro-Quebec in 1962–63. It was led by the then-minister of natural resources René Lévesque, who candidly presented the Hydro-Quebec plan as a step toward ending the subordinate status of Francophones in the Quebec economy; he was fiercely opposed by the Anglophone economic elites.

But it would be a mistake to view the affirmation of the French language in the 1960s as solely a reflection of its material advantages for the rising Francophone middle classes. Montreal in the 1960s was modernizing rapidly, not unlike Chinese cities such as Beijing in the 1990s. For the Anglophone community, Montreal seemed to be on the verge of becoming a truly world-class city. In 1965, the former deputy minister of education in Quebec W. P. Percival could introduce his book on Montreal with the words, “Montreal is in the most vigorous and progressive period of its growth. It is probably not an overstatement that no Canadian city is its equal in this respect.”15 Ironically, those words were written at the same time Montreal was being overtaken by Toronto as Canada’s city of commerce. But such trends were not obvious to Anglophones at the time. Montreal’s population was growing rapidly (city planners envisioned a city of seven million by 2000,16 but its population never went higher than four million), the city was building the world’s most modern subway,17 it became one of the world’s leading centers of the architectural avant-garde18 (similar to Beijing in the early 2000s), and it was chosen to host the international exposition (Expo) in 1967 and the Olympics in 1976 (which became the most costly debacle in Olympic history).19

But for the Francophones, as for many urban Chinese today, modernization also had a downside: their traditional value system seemed to have collapsed and modernization led to a kind of atomism and psychological anxiety. There was more competition for different kinds of social status and people seemed to become more instrumental and materialistic. Hence, pride in language came to the psychological rescue, so to speak. Language was viewed by Francophones as a sign of continuity, a repository of their own history that was being undermined by rapid social change. As recalled by Fernand Dumont in his retrospective on the change of identities affecting Quebec during the Quiet Revolution, “the past was revived, in the 1960s, by another way that had little to do with the more or less abstract discussions about nationalism. Is language not the most concrete part of our heritage?”20 Just as Confucianism has recently been revived among Chinese people seeking roots in a period of rapid social change, so language became the psychological ballast that provided a sense of continuity among Quebec Francophones in the 1960s.

So the growth of the Quebec state was accompanied by a language-based nationalist movement that campaigned for a separate state, led by René Lévesque, who would quit the Liberal Party and take the Parti Québécois to victory in the provincial elections of 1976. Without an independent state, it was felt, Francophones could not overcome a history of economic marginalization and protect their language from assimilation in a “sea of English.” In the 1960s, however, the violent wing of the proindependence forces was more dominant in the eyes of the public. Terrorists of the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) planted bombs in Montreal mailboxes and addressed a notice to the population of the state of Quebec calling for independence or death. From 1963 to 1970, every ten days, on average, a bomb was planted in Quebec province.21 The violence culminated in the October Crisis of 1970. The FLQ kidnapped and murdered the Quebec labor minister Pierre Laporte and was holding the British trade commissioner James Cross. The Canadian prime minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau retaliated by invoking the War Measures Act and sending military troops into Montreal, something Montrealers hadn’t seen since the failed rebellion of 1837. Civil liberties were suspended and hundreds of suspected FLQ “sympathizers” were rounded up. Trudeau is widely considered to have overreacted, but the crisis was resolved peacefully and the rise of the Parti Québécois (PQ) would provide a nonviolent democratic outlet for growing language-based nationalist sentiment.

As a ten-year-old boy, I recall riding in a car with my Anglophone grandfather. Seeing a banner that read, “DOWN WITH BILL 22!” I asked him, “What’s Bill 22?” His faced turned red and he told me that it was something bad, without telling me why.

The next major conflict over language occurred in 1974, when the Quebec premier Robert Bourassa drafted a language bill known as Bill 22. Beginning in the mid-1960s, projects of the provincial, municipal, and federal governments began channeling activity eastward to traditionally French-speaking areas. Most conspicuously, the 1976 Olympics were to be hosted on the far east side of Montreal. But the aspirations of Francophones for collective self-expression of “normal” majority prerogatives were not fulfilled. So Bourassa proposed Bill 22, which aimed to quiet language-based nationalism by passing a language law that declared French the province’s (and thus Montreal’s) only official language. But the Francophones were upset that the bill contained no concrete provisions for implementation, and the Anglophones were even more outraged by the abrogation of free access to English-language schools and the fact that English was being denied its historical place in Montreal and Quebec society. Anglophone voters punished Bourassa by voting for smaller parties in the 1976 provincial election, but their comfort was short lived as the stunning victor in the 1976 elections was none other than the proindependence PQ. The dream of independence has not been realized (as of 2011), but the PQ would go on to implement language policies “that actually made some Anglophones look back with nostalgia at the policies of Bill 22.”22

My mother was elated at the victory of the PQ. So was I. At school, I was being taught history by an elderly Anglophone teacher who taught the subject as a succession of British military victories over the French.23 I felt sorry for the French and was secretly cheering for them.

The PQ immediately went to work to redress economic inequalities. In 1977, it promulgated Bill 101, a language bill that was instrumental in improving the economic prospects of Francophone Montrealers. The language of work was henceforth to be French not just in government but also in key sectors of the private economy. All large companies of more than fifty workers were subject to “Francization” programs, which had the effect of increasing the demand for Francophones in the high-wage occupations of the private sector. Within a generation or so, a deliberate state-managed strategy succeeded in sharply narrowing the economic gap between Anglophones and Francophones.24

But it wasn’t just about economic power. Even if the language policy harmed Quebec’s economy, the Francophone majority was willing to pay an economic price, perhaps in line with traditional Canadien values that prioritized “spiritual” over material interests. Camille Laurin, a psychiatrist-turned–PQ minister of state for cultural development, was entrusted with the task of developing a language policy, and he explicitly defended the language policy in psychological terms, as “a projet de société that would codify the Francophone reassertion of collective self-esteem launched during the Quiet Revolution.”25 A white paper on language policy unveiled by the PQ in 1977 argued that “Francophone demands have nothing to do with ‘English translations’ that policies of bilingualism will guarantee. It is a matter of protecting and developing, in its fullness, an original culture: a mode of being, of thinking, of writing, of creating, of socializing, of establishing relations between groups and individuals and even the conduct of business.”26

As part of the French language laws, all stop signs were changed to “Arrêt.” In the late 1970s, the “Arrêt” was crossed out on a sign on my street and “Stop” was spray painted over it, presumably the work of an Anglophone nationalist. Several years later, I learned that “Stop” is used in France.

Most famously, Bill 101 mandated that public and commercial signs would be in French only in order to give Montreal a visage français (French face) appropriate to a French city. The provincial premier René Lévesque explicitly laid out the logic that the public face of a city affects the values of its inhabitants: “In its own way, each bilingual sign says to an immigrant: ‘There are two languages here, English and French; you can choose the one you want.’ It says to the Anglophone: ‘No need to learn French; everything is translated.’ This is not the message we want to convey. It seems vital that all take notice of the French character of our city.”27 The signs perplexed American tourists from south of the border, and perhaps negatively affected the tourist trade, but language policy was not just about economics.

Bill 101 also reduced the freedom of choice for the language of instruction. English-language schools would henceforth be limited to kids with at least one Anglophone parent with historical roots in Quebec. Immigrants were to send their children to French schools, as would the French community. Why would Francophone parents favor a policy that forces them to send their own children to French schools, in effect depriving their children of the economic opportunities offered by an English-language education? In materialist Hong Kong (see the chapter on Hong Kong), the English-language schools generally pave the way for better jobs and few, if any, parents refuse the opportunity to send their children there. Again, the reason is that language policy in Quebec was also about the assertion of a language-based communal identity that was felt to be under threat (in Hong Kong, the Cantonese language is less threatened because 97 percent of people in Hong Kong speak Cantonese, and the neighboring province is Guangdong, where most people speak Cantonese). Economic interests matter, especially given the unfair economic advantages of the Anglophone community, but they can be subordinated to “spiritual” matters in cases of conflict. And there is also a certain logic to the Francophone view. If all Francophones have the choice of sending their kids to English-language schools, then all may take it for fear of limiting the economic opportunities of their children. Imagine an ambitious middle-class Francophone parent in Montreal: she may prefer sending her child to a French school, but if her neighbor sends her child to an English school, her own kid will lose out and thus she will also send her kid to an English school, even at the price of collective linguistic suicide, so to speak. But if the English schooling option is closed to all members of her community, then she can safely send her kid to a French school without fear of harming her child’s job prospects (in Quebec).

My Anglophone aunt and her family packed their bags and moved to Toronto. I’m still close to them and I see them every time I visit Toronto, but they seem to have lost their attachment to Montreal, other than the occasional craving for Montreal-style bagels and smoked meat. Their grandchildren, born and bred in Toronto, cheer for the Toronto Maple Leafs rather than the Montreal Canadiens hockey team.

Not surprisingly, there was a strong Anglophone response to the new government and its language policy. Shortly after the PQ victory, the powerful Anglophone capitalist Charles Bronfman said, “Make no mistake, those bastards are out to kill us.”28 From 1976 to 1986, the Anglophone community in metropolitan Montreal declined by ninety-nine thousand people (one-sixth of the Anglophone population). Several prominent companies such as Sun Life moved their headquarters to Toronto, confirming the city’s status as Canada’s commercial and financial center. Yes, Anglophone flight had started earlier,29 and perhaps new opportunities for Francophones helped to balance the loss of jobs in the Anglophone sector, but few would deny that the PQ victory did have an economic cost. But again, it wasn’t just about the economy. For Francophones, it was mainly about using the state to secure an environment where they could express their language and culture without fear of being swamped in a sea of English, as happened to Louisiana.

Nor was it just about the economy for Anglophones: it seemed that the world they knew was coming to an end. The writer Mordecai Richler best expressed the Anglophone angst at the time: “The young, having set themselves up in Toronto or the West, will be coming back only for funerals. English-speaking Quebecers will continue to quit the province. The most ambitious of the new immigrants will naturally want their children educated in the North American mainstream (that is to say, in English), so they will settle elsewhere in Canada. Montreal, once the most sophisticated and enjoyable city in the country, a charming place, was dying, its mood querulous, its future decidedly more provincial than cosmopolitan.”30 But Richler was too pessimistic. A more tolerant and multicultural city would emerge from the wreckage of the language wars. Not a world power, perhaps, but a morally improved and even more charming postcolonial city.

My Anglophone grandmother taught me a Yiddish song as we washed dishes together after her delicious meals. To this day, I can still sing it, though I don’t understand what any of the words mean. I know only one other Yiddish word—schmuck—which my father taught me to say when I was two years old in order to shock his mother.

Montreal, like other North American cities, has attracted many different kinds of immigrants over the course of its history. Large numbers of Jews, fleeing dangerous conditions in Europe and Russia, settled in Montreal, and Yiddish became the third most important language in the city.31 In 1931, there were some sixty thousand Yiddish speakers in Montreal, and the community functioned with a considerable degree of independence from the mainstream Anglophone and Francophone communities. For a while, Yiddish became the basis for a flourishing literary and community life, and Montreal became known as “Jerusalem of the North.”32 But most Yiddish speakers did not pass the language on to their children and today the language has pretty much died out in Montreal.

Why hasn’t the “death” of Yiddish in Montreal become an occasion for social conflict in the city? The main reason is that Jews typically regarded themselves as immigrants seeking integration, and the loss of Yiddish was not viewed as a cause for social protest. More generally, as Will Kymlicka argues, immigrants typically wish to integrate into the larger society and to be accepted as full members of it. Their aim is not to become a separate or self-governing nation alongside the larger society; at most they seek to modify the institutions and laws of the mainstream society to make them more accommodating of cultural differences, like Sikh motorcyclists campaigning for the right to wear turbans. Such groups differ from long-established, self-governing, and territorially established “national minorities” such as Francophones in Canada. National minorities typically wish to maintain themselves as distinct societies and they demand various forms of political autonomy, if not complete independence, to ensure their survival as distinct societies.33

As a kid in the 1970s, I lived in an ethnically diverse neighborhood called NDG and many of my friends were descendants of recent immigrants. I played street hockey with my friends Angelo and Frankie, who spoke Italian at home (I recall one occasion when a friend was called home for dinner in the midst of an exciting game, and after his mother closed the door he proceeded to swear at her in Italian, to the general amusement of all; to this day, I can recall a few swear words in Italian). But we all spoke in English on the street and my friends went to Anglophone schools.

What did lead to social conflict was the language of instruction for immigrants to Montreal. Until the mid-1970s, almost all immigrants sent their children to Anglophone schools for the understandable reason that it increased their economic opportunities.34 But it is equally understandable that such practices led to resentment on the part of Francophone Montrealers who wanted to equalize economic prospects for members of their linguistic community.

On the Francophone side of my family, my grandfather was one of eleven children in his family, and my grandmother one of nine. My grandmother had seven children. My mother had two. I have one.

Moreover, the birth rates of Francophones plunged in the 1960s and 1970s, leading to dire predictions that Francophones would eventually become a minority in Montreal and perhaps become extinct as a community in North America.35 So when the PQ was elected in 1976, one of its key policies was to force new immigrants to attend French school. Bill 101 effectively curtailed access to English-language schools for immigrants and ended any threat of Francophone minorisation in Montreal public schools. Between 1976 and 1987, the number of schoolchildren in Montreal receiving instruction in English-language schools fell by 53 percent. And well over one-third of those pupils were enrolled in French immersion programs. As Levine puts it, “Bill 101 accomplished the Francophone nationalist goal of turning English-language education in Montreal into a ‘privilege’ for a narrowly defined community of Anglophones, not a system that integrated immigrants and threatened the Anglicization of Montreal.”36 Although Bill 101 may seem unjust to Anglophones and allophones (those whose mother tongue is neither French nor English)—and still is often seen as such by members of those communities—Levine goes on to note that Quebec schools were replicating the function of schools in the rest of North America: “The most radical impact of Bill 101 on Montreal’s French-language schools has been to introduce a function that urban schools throughout the United States and English Canada have performed since the mid-nineteenth century: integrating newcomers into the language and culture of the city’s majority.”37

At first, the idea was to assimilate the immigrants into Quebec Francophone culture as though the cultures and languages of the immigrants would simply disappear into an American-style “melting pot.” The PQ concept of Quebec culture in 1978 was rooted in the French-Québécois heritage without allowing for the possibility that the heritage could be enriched by the contributions of more recent immigrants. Such ethnic, if not race-based, ideas of nationhood persisted until 1995, when the PQ leader Jacques Parizeau blamed “money and the ethnic vote” for the defeat of the second Quebec referendum on independence.38

A few years after the divorce, my mother met Anthony Meech, a British man who had lived in Montreal since the 1950s without ever having changed his nationality. A proud Brit, Anthony is visibly moved when he watches the Queen’s annual New Year’s address. Thirty years later, my mother and Anthony are still in love, living in a retirement home in Westmount, formerly the bastion of English rule. My mother now votes for the Green party. Anthony treated my sister and me as his own children and was a rock of stability in turbulent times. For several years, my father lived with Sonja, a woman of Austrian heritage, and her children, Lance and Sandi, are like siblings to my sister and me. After Sonja and my father broke up, my father married Odile Jules-Perret, a Frenchwoman. Odile and my father eventually moved to Paris and I visited them several times, especially during my graduate studies in the United Kingdom. They were married for ten years before my father succumbed to lung disease. I still go to Paris to see Odile and her son, Ugo, a kind of half brother to me (see the chapter on Paris). Meanwhile, my sister, Valérie, married a Rastafarian in Jamaica, Alfonso, who recently succumbed to a heart attack in Montreal. Valérie cared for our father during the last three years of his life and now works as an electrician, one of the few females in an all-Francophone work environment. Her son, Oliver, now twenty-two years old, towers over me, and I no longer dare play basketball with him. While I was studying in the United Kingdom, I met Song Bing, a graduate student from China, and we married shortly thereafter. My wife learned French and I learned Chinese. We have one child, Julien Song Bell. I still love Montreal but now live in Beijing and return “home” once a year.

But “facts on the ground” eventually changed perceptions and ideals in the Francophone community. Throughout the mid-1970s, the clientele of French-language schools was composed almost exclusively of French Québécois, but by 1987 more than 25 percent were non-Francophone and more than 35 percent were not of French-Québécois ethnic origin. In 1981, the provincial Ministry of Immigration was renamed to include “cultural communities” in its mission, and the government outlined ways to preserve minority subcultures while integrating groups into Quebec public institutions.39 The new multicultural outlooks have also enlarged Francophone Quebec’s consciousness of its past and present, with more translations of the literary contributions of other cultural communities into French. As Sherry Simon puts it, “Translation is possible now because French no longer has to compete with other histories on its own territory; it can absorb them. French in Montreal has become a ‘language of translation,’ no longer only in the sense of a language obliged to translate, but one that has ample enough room to contain other histories.”40 This more open cultural disposition is perhaps best symbolized by the decision of Quebec’s best-loved Francophone playwright, Michel Tremblay, to allow his play Les Belles-Soeurs to be translated into Yiddish and performed in 1992 (previously, he had forbidden a production in Montreal in a language other than French).41 The law banning the use of languages other than French on public signs was revised in 1997 to allow for second languages (so long as French is more prominent), and such openness no longer generates much public debate, reflecting the Francophone community’s increased confidence.

Although many Anglophones left after the PQ victory, the large majority did stay behind. The “leftovers” made serious efforts to learn French because French became more important for economic mobility. The French “face” of Montreal also meant that Anglophones had to learn French to navigate in the new environment. Such forced change may have been unwelcome at first, but now Anglophones typically accept the necessity of learning French, and many regard it as a plus.

Today there are still some tensions, but relations between the Francophone and Anglophone communities have never been as relaxed or natural. It is not uncommon for an Anglophone to be speaking in French to a Francophone, with the Francophone reciprocating by speaking in English, both sides making an effort to accommodate each other. The main reason for the improvement of social relations is the exceptionally rapid bilingualization of the Anglophone community, especially among the young.42 Today, 62 percent of Anglophones are bilingual, compared to only 3 percent in 1956.43 In the city as whole, 53 percent of the population is fluent in both French and English (by comparison, only 8.5 percent of the population in Toronto is French-English bilingual).44 The spaces of “the once-divided, former colonial city”45 have also opened up. Prior to the 1970s, Mount-Royal Park in the center of the city, designed in the 1880s by Frederick Olmsted (who also designed Central Park in New York), was the only space shared by Francophones and Anglophones.

In 2009, I made two trips to Montreal. On the first, I was invited to a dinner in the Le Plateau area at the home of a former Canadian ambassador to China. The dinner guests seemed to switch at random between French and English. During the second trip, I joined my friend Annie Billington at a restaurant called Le 5e Péché (The Fifth Sin), also in the Le Plateau area. Annie is perfectly bilingual and finally I asked her what motivates her switch from one language to another. She looked at me as if I had posed a silly question, saying she doesn’t know. Most of the conversation was in French, but I noticed that she switched to English to express more bourgeois concerns about everyday life.

Today, historically Anglophone neighborhoods like NDG have become magnets for educated Francophones, and politically progressive Anglophones take pride in living in the Le Plateau neighborhood in the east part of the city.46 The historic dividing line between east and west, St. Lawrence Boulevard, is one of the most multicultural neighborhoods in Montreal. Another linguistically and ethnically mixed district, ironically enough, is the Saint-Henri neighborhood, which is served by the metro station named after the racist theologian Lionel Groulx. In a sign of the times, Anglophones who still refer to “Dorchester Boulevard” in downtown Montreal rather than “Boulevard René Lévesque” (the street was renamed in 1989 in honor of the proindependence former premier of Quebec) are often viewed by young Anglophone Montrealers as politically out-of-touch reactionaries.

In short, the language wars have given way to relaxed attitudes.47 Anglophones and allophones usually learn French because they want to, and Francophones have become more secure and thus more open. From a separatist perspective, the “reconquest of Montreal” has proven almost too successful: “Ironically, as René Lévesque and others speculated, the cultural security provided by Bill 101 may have taken some of the steam out of Francophone dissatisfaction with the Canadian Confederation and unwittingly undermined the PQ’s effort to secure a majority in support of Quebec independence.”48

My nephew Oliver, who looks black, was fined by a white policeman a few years ago for “loitering” near a metro stop. My sister (who is white) went to court to fight the charges on the grounds that her son had been discriminated against on the basis of race.

Of course, tensions remain. In the 1980s, “the socioeconomic profile of Montreal’s Haitian community looked disturbingly similar to that labeled ‘underclass’ in urban America.”49 In August 2008, a riot took place in Montreal North after the shooting death of a black teen by Montreal police, stemming “from what young people say is racial profiling by police officers who are trying to crack down on street-gang activity.”50 Editorials in the Montreal Gazette still raise occasional complaints about treatment of the Anglophone community,51 though the Anglophone community has given up its futile effort to push for “rights” such as the freedom of choice in schooling and the freedom to choose the language of public signs. Arguably, there remains one “solitude” in Quebec, namely, the Francophones who keep to themselves and do not learn English (at the Francophone Université de Montréal, some freshmen are unable to read English; here in Beijing, my students all read English, and the same was true in Singapore and Hong Kong).52 And the city may “look” less multicultural than cities such as Toronto and Vancouver (even though Montreal has a greater proportion of multilingual people),53 if only because other Canadian cities receive large groups of immigrants from China and South Asian countries who usually prefer to immigrate to English-speaking cities (and Quebec’s immigration policy favors immigrants who speak French).

But overall, it’s hard to argue with the verdict of the American writer Norman Mailer: “Montreal is a great city, a living example of how we can overcome the uniformity of global capitalism that is seeking to turn the world into one vast hotel system with McDonald’s on the ground floor. If you grow up speaking two languages, you learn to perceive things in different ways and you resist conformity.”54 Today, Montreal is one of the most easygoing and tolerant cities in the world, famous for its bohemians55 and playful outlook,56 but without the social disorder and high crime rates that plague other open cities. Part of the city’s identity involves being alive to difference, a consciousness of others that contributes to building a charming and multicultural whole that is greater than the sum of the parts (in contrast, Toronto often seems like a conglomeration of discrete neighborhoods, without much of a common thread or civic life). In other words, the sense of civicism has grown stronger and more inclusive in Montreal at least partly because Montrealers have become more sensitive to cultural difference. The broader political lesson seems clear: as Alan Patten puts it, “the best way to promote a common identity is sometimes to allow difference to flourish. It is in virtue of the fact that one’s own group specificity is recognized and affirmed in the public sphere that one’s attachment to the political community as a whole is strengthened and extended.”57 And maybe there are broader moral lessons too. Can it be that bilingualism founded on equality between language groups has led to moral improvement? Is it possible that moving between languages in unforced ways makes it easier to step outside the self and empathize with others? But maybe we shouldn’t celebrate too early. A deep psychological trauma hit Montrealers of both language groups just as the city was improving from a moral point of view.

IT’S THE HOCKEY, HOSTIE [STUPID]58

As a kid, I thought the Montreal Canadiens were invincible. At a certain point, I even felt sorry for the other teams and secretly wished that the Canadiens would lose once in a while “for the good of the league.” I’d like to think that such sentiments helped to motivate my concerns for global justice, but now I regret ever having harbored such secret thoughts: I may have cursed the team.

The Canadiens are the greatest team in hockey history. From 1975 to 1979, powered by great Francophone forwards such as Guy Lafleur, Jacques Lemaire, and Yvan Cournoyer, they won four Stanley Cups in a row. Here in Beijing, I’m pleased to note that an indoor hockey rink displays pictures of that immortal hockey team. I play hockey every Monday and Thursday nights and proudly wear my Montreal Canadiens shirt (oh, sorry, this section is supposed to be theoretical).

In May 1993, I attended what turned out to be the last game of the semifinal playoff series against the New York Islanders. The Canadiens were leading 4 to 1 after two periods, and I went to the bathroom in a state of exhilaration but noticed that the young Montreal fan urinating next to me seemed a bit depressed. I asked him what was wrong and he said, “Les Canadiens, Coupe Stanley, pis après ça qu’est-ce qu’on fait?” (“The Canadiens, Stanley Cup, WTF do we do after that?”) The Canadiens went on to win a record-breaking twenty-fourth Stanley Cup that year, and some observers were perplexed that the win was followed by angry riots, with cars overturned and rocks thrown through shop windows. But I wasn’t surprised. My bathroom friend must have been there, expressing the most profound sense of existential angst that follows the realization that life can only go downhill from here. The Canadiens have not won the Stanley Cup since then.

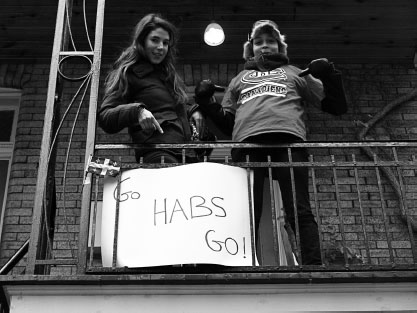

Perhaps the only unifying force in Montreal prior to the 1970s was shared passion for the Montreal Canadiens hockey team. To be more precise, the team unified male members of Anglophone and Francophone communities. New immigrants were largely indifferent, as were most women. The games were often watched in taverns that barred women from entry. But today, support for the team has broadened to include most, if not all, sectors of the population. As Mike Boone puts it, “Hockey is the secular religion here, a passion that transcends linguistic, ethnic, demographic, and socioeconomic lines to unite all Montrealers.”59 The team itself has become much more international, which helps to explain support from immigrant groups (as a kid, my Italian-Canadian friend Angelo supported the Boston Bruins because they had a great player of Italian heritage, Phil Esposito; the young Angelos in today’s Montreal, I strongly suspect, are Canadiens’ fans). As the city has become more egalitarian in its gender relations, many women have come to support the team too (I was surprised recently to hear my sister refer to “our” team, something she never used to do). Another reason for increased female support is that many young women play hockey now. The 2008–9 season was the hundredth anniversary of the Canadiens team, and Canadiens flags were proudly displayed from cars, homes, and stores. A couple of decades ago, people displayed either Quebec flags (to support the Francophone nationalist cause) or Canadian flags (to express Anglophone support for Canadian federalism). Such political symbols are rarely seen now.

Two Montreal Canadiens fans with a Quebec flag—symbol of francophone aspirations—in the background. Photograph © Marie-Eve Reny.

February 27, 2003. My father is in terrible pain, barely able to breathe—in what appears to be the end stage of a terrible lung illness that has gotten progressively worse over two decades. He asks for morphine to end the pain. I tell him he should fight on; there’s still a lot to live for and he has an outside chance of recovery. He says that’s wishful thinking. He asks about the Montreal Canadiens. I tell him they still have an outside chance to make the playoffs, but he says that’s also wishful thinking.

March 1, 2003. The Montreal Gazette has an unusual editorial comparing the fate of the Montreal Canadiens fans to that of a terminally ill patient (even invoking Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s work), and arguing that it is time to resign ourselves to the fact that the Canadiens won’t make the playoffs. I watch that night’s game, against the vastly superior Vancouver Canucks, with my father. The Canadiens nearly pull it off in overtime; they miss very close chances with a power play at the end. The game ends in a tie, and I keep hoping beyond hope that the Canadiens will make the playoffs. And that my father will recover.

March 8, 2003. My father dies. Later that morning, I glance at the paper. The Canadiens lost 3–1 to the Mighty Ducks, dealing an apparent end to their playoff hopes. That night, I dream that my father and I are watching an exciting Canadiens–Red Wings game. The game is tied and, in the dying seconds, the Canadiens miss an open net. The Red Wings come right back and hit, not one, but two goal posts. Even the referee, strangely enough, sprawls in front of the Canadiens net to stop the Red Wings shots. I had planned on leaving because I was so busy, but I tell my father I will definitely stay to watch the overtime. I wake up at that point. I try to force myself back to sleep to watch the overtime, but without success.60

Things looked good for the Canadiens in the 2008–9 season. At Christmastime, I was back in Montreal and overjoyed that my friend Mike Sayig had procured tickets for a Canadiens game against the Florida Panthers (Mike was educated mostly in English schools but now watches the Canadiens’ games on TV in French). The game was thrilling and the Canadiens won in overtime. They were on a hot streak; it was the first topic of conversation among Montrealers at the time, and our team was one of the favorites to win the Stanley Cup. We were all hoping for that perfect hundredth anniversary birthday gift.

The Canadiens are eliminated in four straight games in the first round of the playoffs. What happened to the once extraordinary Canadiens? Why are they so ordinary now? The main reason, I must confess, is that they no longer have an unfair advantage over other teams. Until 1969, the Canadiens had first dibs on Quebec’s first two draft picks, but the practice was abandoned in the name of parity for expansion teams.61 So the team I worshipped in the 1970s was composed of players who played for Montreal because the system was rigged in Montreal’s favor. That’s why so many great players from Quebec played for Montreal, but now they are spread out among other teams. So there was, it turns out, one advantage that benefited both Francophone and Anglophone Montrealers—the only one of its kind—but we lost that advantage to equalize opportunities for other teams.

In May 2010, the Canadiens accomplish a miracle. They rally from behind to defeat the top-ranked Washington Capitals in the first round of the playoffs, and the second-ranked Pittsburg Penguins in the second round. In the Journal de Montréal, the masterful Canadiens goalie Jaroslav Halak is depicted as Jesus Christ in a Canadiens jersey and goalie mask, surrounding by adoring apostles. 62 Unfortunately, I can’t watch the games on TV here in Beijing. My son tells me he watched the last game on his computer in class. I scold him, telling him he should never do that again. Then I ask him for the website address. But it’s not the same. I feel the call of home. I dream about sitting with my father in a Paris café, amazed that even Parisians are talking about the Montreal Canadiens. I look into plane tickets to fly back for the finals. But first the Canadiens must overcome the lowly Philadelphia Flyers in the semifinals. The Canadiens lose in five games, mainly because they cannot withstand the attack of three fleet and skilled young Francophones on the Flyers team: the sort of players who would have been playing for the Canadiens in the past.

Maybe, then, equality isn’t the mother of all values. If I had the power to redo Montreal history, the pre-1969 hockey draft system is the one part I would not have tampered with. The National Hockey League might not be as equal, but the Canadiens would continue to win Stanley Cups. And my father might still be alive.