SPIRIT ISLAND sits in the heart of Nett Lake, on what is today the Bois Forte Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota. Known as Manidoo-minis to the Ojibwe, the island is reminiscent of a drum because of the reverberations that move through the air as one walks over an area of polished rock protruding from the water. The island holds hundreds of carvings of animals, humans, and manidoog. Ojibwe people leave offerings of clothing, food, and tobacco at this sacred place and give thanks for the land, the water, and the wild rice. Prayers are made to the water spirits. The rock itself helps the Ojibwe observe water levels on the rice lake. Some Ojibwe who harvest rice on Nett Lake like to tell stories about memegwesi, small people with hairy faces who stay mostly hidden from sight but live in many ways like Anishinaabeg and harvest the manoomin that grows naturally in the waters bordering the island. Sometimes only the sounds of their knocking sticks are heard on the lake. Nett Lake is geographically situated north of several major watersheds, making it somewhat isolated from pollution and cut off from alterations that have negatively affected water quality and levels since the introduction of the timber industry. The 7,400-acre lake is renowned among Ojibwe people for being among the very best places to harvest wild rice, with the largest-sized grains in Minnesota.

On the surface of Nett Lake during the 1930s, the changes that the twentieth century brought to the Ojibwe way of life were made stark. For generations of Ojibwe women, water was a gendered space where they possessed property rights, which the Ojibwe conceptualized as taking responsibility for caring for the land and water and their resources. For centuries, the wild rice camp had been a female work site. Women’s long-standing practice of binding rice on the lake was about more than just fending off birds and winds; instead it was one part of a highly successful indigenous legal system that empowered women. Yet the 1930s introduced changes to Ojibwe society that by the end of the decade would transform the gendered labor practices associated with the wild rice harvest and challenge the long-defined role of women in Ojibwe life.

When Ojibwe men first entered the realm of women’s collective labor, they did so as wage earners and employees of government work programs. The hard times taking place nationwide in the 1930s were deeply felt in Indian Country. “An Indian family was never without meat or fruit as is now the case,” mourned one St. Croix Ojibwe man. The economic pressure pushed an entire generation of Ojibwe male workers to incorporate emergency relief and conservation employment to their expanding repertoire of labor. The St. Croix Ojibwe man found it necessary to work as a pulpwood cutter for the WPA and sent his daughter to a government boarding school during the Great Depression.1 His solutions were part of a broader trend among Ojibwe families, who survived poverty and hardship through a combination of indigenous seasonal occupations with wage labor and government relief, including boarding school education for children, where food, clothing, and instruction were paid for by the U.S. government.

Day-to-day survival during the Depression dictated that Ojibwe families separate for long stretches of time, which presented an additional hardship for a people who attached importance to the intimacy of working and living closely with kin. Throughout the Midwest, men departed for Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) work camps, and children enrolled in government boarding schools. The system of segregated schooling that the federal government established for American Indians during the assimilation era had been part of Ojibwe life since the opening of the Indian Industrial School at Carlisle in 1879. In the leanest years, when resources at home were stretched impossibly thin and Ojibwe faced widespread destitution, sending children to boarding schools became a way to ensure that they were fed and clothed. Indian boarding schools had their highest enrollments during the Great Depression. Though negative attitudes and racism toward Indians may have lingered, there is evidence of greater enlightenment among teachers, staff, and administrators in U.S. Indian boarding schools during the 1930s, when most schools had formally abandoned assimilation as a goal and the federal bureaucracy was promoting ideas of cultural pluralism. It is more plausible, then, that the population peaked as students and families initiated enrollments, in spite of a long history of disdain or ambivalence about the institutions among American Indians. Ojibwe families had firsthand knowledge of the flaws of boarding schools but nonetheless sought them out for their children as a strategy of family preservation.

A study conducted during the Depression found that nearly all residents of the White Earth Reservation relied on poverty relief or pension programs.2 Ojibwe people continued to count on their relatives and their community, vital networks where cultural patterns of reciprocity, sharing, and generosity were deeply ingrained. An ethic that encouraged one to think for others had always sustained Ojibwe life through hard times, and it played a critical role in ameliorating the effects of the Great Depression. However, decades of land loss and violations of hunting, fishing, and gathering rights were deeply felt and left the Ojibwe with few resources to navigate the perils of the 1930s.3 Great poverty was reported across Minnesota Ojibwe communities by researchers employed in the Federal Writers’ Project.

[T]he average Chippewa today lives at a bare subsistence level, and Government funds alone assure him his necessities. With the exception of the Red Lake Reservation, his lands have been allotted, and such work as he can obtain consists of mere seasonal or odd jobs. Harvesting the wild rice and blueberry crop, picking pine cones for the forest nurseries, and fishing and lumbering are only temporary remunerative tasks. Repeated attempts to re-educate the Indian in his native crafts have met with only partial success, although the tourist trade provides a lucrative market for products of his skill even when they include only the usual birchbark baskets, bird houses, and toy canoes.4

The Federal Writers’ Project—part of the Works Progress Administration, created during Franklin Roosevelt’s administration—published the state guide to Minnesota in 1938. Wisconsin’s WPA project employed a number of Indian writers, and though it is not clear whether any Ojibwe numbered among the 120 writers who participated in the statewide project in Minnesota, the guide incorporated a fair amount of information on Ojibwe communities. It described recent environmental changes on the Bois Forte Reservation and the informal economy that operated during the berry season. Perhaps most markedly, it noted a new arrangement of labor in the wild rice harvest, with men joining women on Nett Lake.

The heavy timber that once covered the district and attracted many settlers has been cut. During the berry season, the Indians from miles around gather in swamps near the village to pick blueberries to sell. The wild rice that grows plentifully in Nett Lake also is harvested by Indians. One man paddles a large canoe while a second threshes the rice heads into it. In camp, the rice is heated in large kettles over open fires to loosen the hulls. Stalks and foreign substances then are shaken or fanned out, and the rice goes into a wooden vat, where a boy wearing moccasins “jigs” the hulls from the grain with a peculiar tramping step. Once again the rice is fanned, then weighed. Wild rice, long a staple in the Indian diet, has become a luxury food throughout the country.5

Wild rice gained some popularity in American cultural habits of food and drink in the 1930s but primarily as a “luxury food,” never the mainstay it was to Ojibwe diets. To the Ojibwe, though wild rice varies slightly in color and size, from small seeds to large Nett Lake grains, it is always perfect. For generations prior to the Great Depression, harvesting and processing wild rice was the vocational specialty of Ojibwe, Dakota, and Menominee women workers in the Great Lakes region.6 Through the reservation era, the lakes remained a strongly gendered space. One September in the late nineteenth century, Joseph Gilfillan, an Episcopal missionary in Minnesota, observed an estimated six hundred Ojibwe women gathered for harvest at White Earth but no men. Traditionally, when the rice was almost ready for harvest, in late summer, men traveled with their families to set up seasonal rice camps, then worked nearby or moved farther on to fish and hunt. Collectives of women were responsible for binding the rice stalks in their pre-harvest state, knocking the ripened grain into canoes, and processing the rice in camp.

Nearly all photographs and documents about Ojibwe wild-ricing before the publication of the WPA guide and the federal work camps of the same era represent a female harvest. Some years before, the Minnesota ethnologist Frances Densmore had noted straightforwardly that “rice was harvested by women.” She began her fieldwork in 1910 among Ojibwe communities in Wisconsin and Minnesota, and her ethnographically rich collection of photographs portray women’s labor at every stage of production.7 She recognized the wild rice camp as a female work site, and she photographed women paddling canoes through lakes dense with wild rice, emptying large winnowing trays full of green rice, stirring the rice on mats of birch bark with long wooden sticks, and sitting before smoky fires to parch it. Densmore was fascinated by the way women bound stalks of rice pre-harvest, correctly identifying this as a significant practice for Ojibwe women and their communities.

The long-established ritual of binding strips of basswood fiber around the stalks was fundamental to how women took responsibility for caring for the land and water and their resources. Densmore photographed and described the practice.

Each group of relatives had its share of the rice field as it had its share of the sugar bush, and this right was never disputed. The women established it each year by going to the rice field in the middle of the summer and tying a small portion of the rice in little sheaves. The border of each tract was defined by stakes, but this action showed that the field was to be harvested that year. 8

For centuries in the Great Lakes, binding rice was a way for women to protect the crop in its unique ecosystem, as well as a significant part of their indigenous legal system. The Oshkaabewisag, elected ricing committees of men and women, was also responsible for taking care of their resources and held an indispensable position in organizing the harvest.9 Albert Jenks, an anthropologist who worked in Wisconsin and Minnesota and along the Canadian border at the turn of the twentieth century, wrote in great detail about women’s labor in the wild rice economy. He observed how they incorporated and instructed their children as they went about their work, and he explained the indigenous system in which female collectives not only labored together but organized the distribution of wild rice. According to Jenks’ 1899 fieldwork, “the women of more than one family frequently unite their labors and divide the product according to some prearranged agreement or social custom.”10

A similar system operated at Mille Lacs. An Ojibwe man born in 1918, Jim Clark, remembered his great-grandmother’s rice camp and the decisions she made “about who would camp there”; he also spoke of how the women in his community controlled the entire social organization of the harvest on the upper lakes of the Rum River.11 Through their labor and community-based institutions like the Oshkaabewisag, Ojibwe women constructed an extraordinary legal framework and an orderly system of ecological guardianship to manage the wild rice economy. Increased non-Indian settlement in northern Wisconsin, Minnesota, and areas along the Canadian border led to a reduced wild rice district by the time Clark’s generation was born and posed further threat to the wild rice environment.

Given how important the practice of binding rice was, historically, to Ojibwe women, it is rather shocking that it disappeared in Minnesota and Wisconsin around the end of the Great Depression, suggesting that the prior decade was a time of revolutionary cultural change in their lives. Not only did outside intervention by government and commercial forces change the gender balance of the rice harvest; it also challenged the integrity of the harvest itself. When lumbermen in Canada and the United States built dams in order to float logs downstream to be milled, they wreaked havoc with water levels in streams, rivers, and lakes. Wild rice grows well in waters with gentle currents and steady water levels, but even heavy rains can cause crop failure, and dam construction has been lethal.12 The creation of the seventeen-thousand-acre Chippewa Flowage in Wisconsin by the Northern States Power Company in 1923 inundated the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation, destroying villages and graves and wiping out its wild rice.13 In a similar story, work by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers beginning in 1884 devastated native wild rice stands at the Minnesota headwaters of the Mississippi River, and dam construction and alterations caused wild rice that once thrived along the river to decline.14

Ojibwe people have observed that wild rice seems to follow four-year cycles that include intervals when the harvest might fall short.15 The way of life the Ojibwe established in the Great Lakes region was not immune to hardship. Reservation life was, for the most part, a life of continuous economic struggle, and wage labor became a necessity for families. When the Great Depression struck in the United States, American Indians were among the first to lose jobs and wages, and this additionally burdened a convergence of colonial circumstances that had undermined Ojibwe life since the creation of reservations. Land loss, cultural assimilation, environmental degradation, and the denial of treaty rights had already created squalor and misery in Ojibwe Country before the unemployment and poverty of the 1930s.

At the same time, the resilient generation who remember life in the Great Depression frequently view their hard times through a lens of optimism and credit the resourcefulness of indigenous communities for allowing them to not only survive but thrive relative to other Americans. Jim Clark’s view from Mille Lacs was not uncommon.

I think people in rural areas fared better than urban people. I remember those years when my stepfather and grandma planted more than usual. My dad still had his horses. All of us kids had to help in the gardens. Our parents said it was better to do the hoeing and weeding early in the morning because everything was still damp from dew and it was cooler. We always had meat of some kind—deer, grouse, or partridge, rabbits during the winter. We used to eat porcupine, which I love, muskrats, and fish. People in the cities couldn’t get this stuff and they didn’t have ground for gardening, so I guess we were fortunate to have Mother Earth to depend on.16

The Depression years also found the Ojibwe relying more heavily on work in the tourist industry to combat the poverty in their families and communities. Guidebooks, advertisements, and postcards from northern resorts and Minnesota’s Office of Tourism suggest that the opportunity to view and interact with Indians was a significant draw for vacationers who traveled to the lakes and woodlands, though genuine contact came most frequently through mundane activity performed by maids or cooks.17 Entire Ojibwe families performed and worked in summer pageants held at Minnesota’s Itasca State Park, a fashionable tourist destination that included the headwaters of the Mississippi River, native stands of red and white pine, sparkling lakes, and the newly constructed Douglas Lodge.18 Ojibwe workers from the surrounding White Earth, Leech Lake, and Red Lake Reservations participated in pageants at the popular “Chippewa Village,” erecting teepees and wigwams, paddling birch-bark canoes, holding pow-wows, and occasionally re-enacting battles with white performers.19 Performers could earn extra income posing for photographs; dramatic images that placed indigenous people in the past were especially popular with tourists. In one vintage 1930 Itasca postcard, a young, handsome couple with three children poses next to their fully packed travois, the mother beautifully attired in deerskin and the father in full headdress. For many decades, an “Indian Village” was a feature of the Minnesota State Fair, peaking in popularity during the 1930s. In 1935, the WPA sponsored a state fair pow-wow in St. Paul, and singers and dancers from White Earth exhibited their culture. Fairgoers, invited to view indigenous wild rice harvesting techniques, looked in on a live demonstration as an Ojibwe woman parched rice.20

During the Depression some Indian people in the western United States joined family camps operated by the Civilian Conservation Corps–Indian Division. The Lakes States Region of the CCC-ID, operated by the Department of the Interior’s Office of Indian Affairs, offered relief work to Ojibwe and Dakota people in Minnesota, as well as to Indians in Wisconsin and North Dakota. Minneapolis was the Great Lakes regional headquarters for the CCC-ID, and, not surprisingly, men received most of the paid positions in the emergency relief program. In 1933, shortly after the CCC-ID’s national program for American Indians commenced, the corps’ first camp in northern Minnesota opened on the Red Lake Reservation. For the most part, young men over the age of seventeen were recruited to the camps through their agencies; the men then traveled considerable distances in northern Minnesota, separating families, and bunked for weeks at a time in emergency work camps. Men were rotated in and out of jobs to widen the pool of those participating in relief work. The handbook of the CCC-ID suggested subordinate roles for Indian women in poverty relief programs, saying they could serve camp matrons or assist in “recreation and leisure-time activity as will make camp life attractive.”21 Employees received a modest salary of thirty dollars a month; they contributed a small sum for their own food and shelter, and the program dispensed their remaining wages to dependents and relatives. Some workers who lived closer to the work camps lived at home, as did many men from Ojibwe communities at Red Lake, White Earth, Lake Vermilion, and Grand Portage, who were then eligible for a monthly salary of forty-two dollars.

In Michigan, too, there were opportunities for Indian men and women to find work. Camp Marquette opened in 1935 under an agreement between the U.S. Forest Service and the Office of Indian Affairs, employing more than 150 Ojibwe from the Bay Mills community and the Upper Peninsula. Ojibwe workers constructed roads, parks, and fish hatcheries and designed forest and water restoration projects. Camp Marquette had a baseball team and a sweat lodge. The Bay Mills community, which had struggled for decades to have the federal government recognize its sovereignty and treaty rights, found new support from John Collier, the commissioner of Indian Affairs (1933–1945), and his administration. In 1937, the small community held its first election on the reservation, in which Lucy LeBlanc was elected vice president. When the president was called to a position with the Office of Indian Affairs shortly after the election, Lucy became the first Ojibwe woman to serve as a tribal president, perhaps the first American Indian woman to lead a tribe in the modern era.22

A small number of Ojibwe women also found employment as social workers for the U.S. Indian Service, investigating the problems of needy Indian families during the Depression. Isabella Robideau, an Ojibwe woman working from the office in Cloquet, Minnesota, held an influential position in the Lake Superior region of Wisconsin and Minnesota, recommending men for hire in CCC-ID work camps and organizing financial arrangements for their dependents. Indian men wrote respectful letters to Robideau seeking her permission to enter work camps. This one came from several men living in Danbury, Wisconsin, written April 6, 1935:

Dear Mrs. Robideau,

Will you please help us to enter the C.C. camp at Gheen whenever it reopens again? We just have to work in order to live and as you know, no work around here.

Please let us know whether it will be open April 15. Also how should we get there?

Yours truly,

Albert Churchill

John Dunkley

William Premo23

Robideau’s correspondence displays the confidence with which she meted out advice to camp foremen regarding their employees, on matters including the distribution of men’s salaries to their relatives, which meant parents and other adults as well as wives and children. In 1937, she wrote to the agency superintendent regarding the CCC-ID’s practice of hiring white men married to Indian women. Her letter suggests that Ojibwe men working for the Fond du Lac CCC-ID mobile unit near Cloquet had circulated a petition favoring the employment of a non-Indian who was a veteran of World War One, “attended council meetings faithfully,” drove a “ramshackled car that he takes seven men to work in,” and had married Kate Pequette, a Fond du Lac tribal member. The veteran, his wife, and their three tribally enrolled children were all “accepted as an Indian family” and valued as community members.24 Robideau’s correspondence about the Pequettes suggests the fluidity of Ojibwe family life during the Great Depression and the continuing importance to them of kinship and contributing to the common good, rather than their adoption of American concepts of race and blood quantum that characterized the reservation and allotment eras.

In a letter he wrote to the Consolidated Chippewa Agency in 1935, Commissioner John Collier emphasized that “married men with families” be given priority in hiring practices of the CCC-ID.25 Robideau then explained to her non-Indian colleagues in the CCC-ID that Ojibwe men were very reluctant to leave their homes and families and would do so only as a last resort. At a time during the Depression when “county relief was slim and rather difficult to obtain,” Ojibwe men had few alternatives to joining the program to build roads, restore forests, or work on housing projects.26 Alphonse Caswell, an Ojibwe graduate of the Flandreau Indian School, in South Dakota, watched for forest fires as a WPA employee at home on the Red Lake Reservation. Projects varied at Red Lake, still thick with pine forests, a community that had strategically avoided allotment and retained a substantial communal land base. Workers there cleared fire hazards, cleaned off roadsides, “brushed” truck trails, cut new telephone poles, and improved the stands of forest that stretched over several thousand acres of tribal land. An impressive tree nursery project was in full operation by 1940, along with a project to control a blight of white pine blister rust. Ojibwe artist George Morrison, born along the north shore of Lake Superior near his reservation, began work in the CCC-ID camp in Grand Portage, along with young Indians from across Minnesota—“good healthy work” that encouraged friendship among the people assembled in the camps from a number of Ojibwe communities in the Great Lakes.27 They lived in barracks, dined communally, and played baseball. In the forests, they attacked the blister rust, pulling diseased white pines out of the ground by their roots.

The landscape around the CCC-ID Nett Lake camp, near the premier wild rice lake, became “a city in miniature,” transformed overnight by brown tents in 1933. These gave way to more permanent “neat pine structures, built by Indians with lumber manufactured at the Red Lake Indian saw mill.” Emergency conservation workers constructed trails, lookout towers, ranger stations, and telephone lines for more reliable fire detection and control. The camp brought in workers from surrounding Ojibwe communities, including men from White Earth, Leech Lake, Mille Lacs, Fond du Lac, Lake Vermilion, and Grand Portage. In the winter of 1934, a group foreman described the camp at Nett Lake, painting a frigid but bustling scene of activity.

Far to the north, in the frontier country of Minnesota, close to the Canadian border, the Chippewas of the Nett Lake Indian Emergency Conservation Work Camp on the Bois Fort Reservation, continue their conservation work program, despite sub-zero weather, blinding blizzards and a welter of deep snow. It is a country where even thermometers freeze. At Christmas time, the thermometer that survived registered fifty-six degrees below. That night, watchmen were kept busy replenishing the fuel in red-hot stoves.28

Ojibwe men who worked for the WPA and the CCC-ID still helped their families move to seasonal work sites for harvesting wild rice and making maple sugar. The non-Indian manager of the Nett Lake program was shocked when Ojibwe employees virtually abandoned the camp in August to attend to the wild rice fields; even the better-paid overhead machine operators walked off the job.29 Remarkably, rather than fire the men for leaving, managers and superintendents decided to permit Ojibwe wild rice gathering in hard times. They then took the further step of taking charge of and “improving” the indigenous harvest. One early project was to upgrade and restore the historic Grand Portage Trail, an important route once used during the fur trade by Indians and the Hudson’s Bay Company. The trail had grown over with brush, and Grand Portage harvesters who lived at the arrowhead of Lake Superior could not easily reach their rice lakes. Nett Lake employees also worked to regulate water levels for enhanced wild rice management during 1936.

The Ojibwe wild rice economy became a new focus of emergency relief programs in the Great Lakes region for its potential to be “improved” and “modernized” through government management and the labor of men. Work camp managers, initially unprepared and confounded when the men felt it appropriate to leave work to set up rice camps for their families, soon grew convinced that it was irresponsible to ignore a potential source of income and a natural supply of food for the Ojibwe in years of extreme deprivation. Probably they were unaware of the fact that harvesting wild rice was a predominantly female enterprise, and because the work was conducted outdoors and very labor intensive, it fit within their own cultural categories of men’s work. Evidence suggests that the men who made decisions and controlled the labor in federal work programs failed to comprehend, or perhaps simply sidestepped, the issue that must have greatly concerned Ojibwe communities: the traditional wild rice harvest was women’s work.

As more men began harvesting wild rice during the Depression, the Ojibwe slowly came to see the work as gender neutral. By the end of World War Two, Ojibwe men clearly dominated the harvesting and production of wild rice in the Great Lakes region. James Mustache, Sr., an indigenous harvester on the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation, in Wisconsin, who was born around 1903, recalled in late interviews the evolution in wild rice labor that took place during his lifetime. He described his grandmother harvesting wild rice and using burlap sacks for binding material. During the 1930s, men in his community began to harvest rice, and by the latter decades of the twentieth century, few women harvested rice at all at Lac Courte Oreilles.30

The patterns Mustache observed taking place at Lac Courte Oreilles were widespread throughout Wisconsin and Minnesota during the Great Depression. It does appear that the original impetus for Ojibwe men to harvest wild rice began with their employment in the poverty relief programs, where they put into operation rice camps in a rational effort to preserve the well-being of their families and communities. The Works Progress Administration, the Indian Division of the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Minnesota State Forest Service, all of which primarily employed men, helped them establish a new version of wild rice camps to reinvigorate the depressed Ojibwe economy.

In the process, government employers introduced to the harvest their own culture’s notions of masculinity, physical labor, and the work ethic. In Minnesota, the State Forest Service encouraged an increasingly male-centered project of wild rice management that emphasized male supervision and masculine industry. Labor that had historically been organized and carried out by large collectives of Ojibwe women was now increasingly tackled by male work crews and even non-Indian managers.31 The most conspicuous evidence of the entry of Ojibwe men into the harvest during the 1930s was a large-scale project developed when the Minnesota State Forest Service set aside five acres of nontribal land near the Rice River as the Indian Public Wild Rice Camp on the White Earth Reservation, cooperating with the U.S. Indian Service to oversee rice harvesting by permit.

At Rice Lake, Ojibwe men were employed to construct “Indian rice camps” complete with modern conveniences. A report detailed this “modernized” campground, referred to as Project Number One, where hundreds of Ojibwe gathered. After Ojibwe workmen built a new dock across swampy water to the lake, erected six latrines, and thinned aspen and birch trees to open roads to the five-acre wild rice camp, the men began to harvest rice from the lake. In photographs, men in overalls pole boats and knock rice, while the hulling operation also was “a masculine affair.”32 Managers writing to Washington about Project Number One argued that wild rice should continue to be supported with public funds, ending with the comment: “Within the past three years the State of Minnesota has realized the importance of wild rice to the Indians.”33

Efforts to bolster the wild rice economy in a government-sponsored wild rice campground at White Earth must have seemed ironic to the Ojibwe men and women who experienced the Great Depression. Anyone remotely familiar with recent history would have understood the terrible devastation to the wild rice economy that had recently taken place in Minnesota and Wisconsin. The same government that had for almost a century privileged the timber industry and agriculture over Ojibwe interests to the point of devastating the wild rice environment, and had forced an allotment policy that piece-by-piece undermined Indian land-ownership, now “realized the importance of wild rice to the Indians.” For the past fifty years of wild rice habitat decline, the Ojibwe vigorously defended their responsibility of caring for the land and water and their resources. Seemingly overnight, government officials and the State Forest Service in Minnesota yielded to an indigenous economy it had worked for the previous half-century to destroy. The Ojibwe seasonal round came back to life during the Depression, in some places with federal and state endorsement and supervision, to solve the problem of Ojibwe poverty. In another incongruous move, government officials showed instructional photographs at community meetings on the White Earth Reservation to highlight the excellent practices of maple syrup farmers from Vermont. They also suggested the importance of programs to instruct Ojibwe men in the harvesting of maple syrup.34

Yet, as the government took charge of organizing the wild rice harvest to solve Ojibwe poverty, it also managed to undercut those efforts by allowing production of wild rice to expand beyond the Ojibwe. The number of non-Indian harvesters and rice buyers multiplied, and the first state regulations of ricing appeared, requiring licenses of all harvesters. Commercial firms and individual buyers soon entered the market, purchasing green wild rice from harvesters, then mechanically processing the grain for sale. When the state of Minnesota began to issue ricing licenses, in 1939, the Ojibwe right to harvest remained protected, but the majority of licenses issued went to individual non-Indians.35

The entrance of inexperienced non-Indians into the harvest had dire consequences for both wild rice habitats and Indian economies, as Charles Chambliss, a Washington, D.C., agronomist who studied wild rice, found in the late 1930s.

During the past eight or ten years there has been a steady growth of whites entering the wild rice beds. They have been greedy and paid no attention to the natural laws regarding the plants’ reproduction. As a result many of the better wild rice beds have been ruined by whites gathering the crop in an immature state. The practice of the whites has forced the Indians to gather immature rice. This whole entire practice was ruining the wild rice in Minnesota.36

Historians often think of the Great Depression as a time when government officials collaborated with Indian communities to address the terrible problem of Indian poverty and federal work programs were part of a larger effort to rebuild trust.37 State and federal entities, along with affiliated missionary organizations, had for many years made it a priority to organize the labor of indigenous men and women in ways that conformed to Euro-American notions of female domesticity and male agricultural production. These gender-based attempts to restructure family and community life are associated with misguided “civilization” policies of the previous century, rather than the “Indian New Deal.” Yet it is interesting to find that during the 1930s, a dire time when poverty relief work became a necessity for the Ojibwe, federal and state agencies once again embarked on an effort to reshape labor practices, especially as constructed in relation to gender.

The establishment of wild rice campgrounds did represent collaboration with Indian communities, and women and families were not excluded from them. For men, an opportunity to earn a government paycheck to help their families was a great incentive, even though it may have involved a significant change in Ojibwe cultural practices. At the government wild rice camp set up in northern Minnesota, women and children were welcome to wait on shore and take part in processing the harvest while men knocked the rice. It does not appear that Ojibwe people greatly resisted a change that surely amounted to a revolution in their communities. In a time of extreme economic uncertainty, men joined women as active harvesters of wild rice, moving into the gendered spaces where Ojibwe women sang harvesting songs and labored together in support of their families and a rich community life.

The WPA state guide to Minnesota blithely pronounced in its 1938 publication, “The most hopeful indication of the possible economic redemption of the Chippewa is their growing awareness of the advantages of group effort.”38 Given the history of the Ojibwe in the Great Lakes region, who regarded family and group labor (much of it involving separate male and female collectives) as the essence of community life, such a statement demonstrates pointedly how little government entities truly understood about the indigenous people whose lives they presumed to reshape. The guide was simply referring to the arrival of a new wild rice cooperative on the Leech Lake Ojibwe Reservation in northern Minnesota that opened in 1934.

Today many sell their products through the recently founded Chippewa Co-operative Marketing Association, which began with a capital of $100,000 from the tribal treasury. It not only insures the craftsman a better price for his wares, but also sponsors a wild rice cleaning and packing factory designed to replace the primitive harvesting and cleaning methods still used by Indians in the north woods. Eventually the making and marketing of maple sugar will be added to the co-operative’s undertakings.39

Photographs of Ojibwe people harvesting rice are a useful means of tracking changes in the work of men and women, and it is obvious that men grew more active in the enterprise during and after the Great Depression. Through the years until the present day, women are pictured harvesting rice with family members or husbands, though female collectives ceased to exist.

In 1934 the Ojibwe established a wild rice cooperative in northern Minnesota. Co-op members, primarily from Leech Lake but also from White Earth, could vote and share in any dividends that resulted. The cooperative elected officers and paid wages directly to harvesters who brought in rice. The manager of the cooperative was Paul LaRoque, an Ojibwe man from Beaulieu, Minnesota, who also served as rice buyer, paying out amounts that varied annually from fifteen thousand to thirty thousand dollars to purchase finished wild rice from Ojibwe harvesters.40 The Indian agency in northern Minnesota purchased wild rice from the co-op to supply food for relief cases in the native community.41 Letters from the co-op show that LaRoque corresponded with a wide range of individuals and businesses, from D’Arcy McNickle, the Flathead employee of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, to the managers of the Curtis Hotel in Minneapolis, who also purchased Ojibwe-harvested rice. LaRoque answered everyone who wrote to the co-op, and he diligently promoted wild rice in Minnesota and throughout the United States.

Dear Mrs. Skifstrom:

You are the winner of the Wild Rice Guessing contest, which was held in Bemidji during the Paul Bunyan Carnival, your guess being 12,600 and the correct figure was 12,576 kernels. Your 5 lbs. of No. 1 wild rice is being shipped to you today.

Sincerely yours,

Paul LaRoque, Manager

Wild Rice Corporate Enterprise

Mr. D’Arcy McNickle

C/o Indian Office

Washington, D.C.

February 8, 1940

Dear Mr. McNickle:

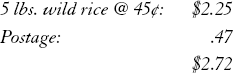

Thank you kindly for your order of five pounds of No.1 Wild Rice. Your order was shipped out yesterday afternoon. The charges are listed below:

Your check or Money Order should be made payable to Paul LaRoque, Manager, Wild Rice Corporate Enterprise.

We will be glad to fill any other wild rice orders you may have at any time.

Sincerely yours,

Paul LaRoque, Manager

Wild Rice Corporate Enterprise

The co-op’s records show that, despite the shift in gendered labor, women were active in the organization and retained a foothold in the wild rice economy.42 Three women referred to by name in the co-op records, Mrs. Kate Nelson, Mrs. Lovelace, and Mrs. Broker, and one other unnamed Ojibwe woman, were important harvesters for the cooperative in the late 1930s, and the co-op delivered barrels to all four women for parching rice. The cooperative described the rice it sold to the public as “parched, finished, and graded under careful and expert supervision,” a testimonial to the practiced skills of its Ojibwe women participants. One of these, Cecelia Rock, managed the cooperative during the early 1940s, but perhaps this position may have been temporary due to the absence of Ojibwe men during the war years.

Gedakaakoons, a young Ojibwe who helped market rice for the cooperative, was photographed in her jingle dress, amid Ojibwe handicrafts made by women, in the co-op’s log warehouse on the Leech Lake Reservation.43 The image shows her holding a bag of wild rice that pictures a drum with feathers. In her outfit, she greatly resembles one of her Minnesota commercial contemporaries, the “Indian Maiden” pictured since 1928 on Land O’Lakes dairy cartons. Land O’Lakes is an old Minneapolis–St. Paul company, also a cooperative. The Ojibwe wild rice cooperative may have appropriated the maiden for their own advertising purposes in the 1930s, from a regional company that had recently appropriated this image from Indians in Minnesota.44 That an Ojibwe cooperative employed an “Indian Maiden” in their modest marketing campaign was not a sign of the demise of Ojibwe women as active harvesters but, rather, a creative adoption of an already popular image of Indian womanhood. The cooperative lasted a decade, surviving the Depression but not World War Two, and closed in 1944.

Women continued to harvest wild rice with their families in other areas of the Great Lakes region. In 1939, the year Minnesota harvesters were required to purchase ricing licenses, a number of women harvested rice at Portage Lake and Perch Lake in central Minnesota, contending with non-Indian harvesters who had picked rice that was too green and a game warden who had forced Indians off the lakes. Despite harassment, one woman reported an increase in her harvest over that of the previous year, when water levels were low, bringing in four hundred pounds of green rice.45 Some Ojibwe women applied for licenses to harvest wild rice, including Naomi Warren LaDue of White Earth, who complained of a long trip to Bemidji to pay her fee to the game warden.46

Ricing licenses, new methods of processing rice, non-Indian harvesters, commercial buyers, and the introduction of government wild rice campgrounds deeply influenced Ojibwe labor practices associated with the harvest in the years following the Depression. Once again, indigenous women adapted, preserving the fundamental structures of Ojibwe society by working with the wild rice cooperative at Leech Lake and ricing by state permit when that became a requirement. They continued to harvest wild rice, laboring alongside other women and an increasing number of male relatives, in the 1930s and 1940s, though by 1940 they were no longer a majority.

A new population invaded the lakes in postwar America, building summer homes and new economies around tourism while advancing popular ideas of leisure and landscapes of recreation—a lifestyle that continues to ravage land, water, and their resources. The Ojibwe have never ceased their efforts to legally protect wild rice, and today the opening of the wild rice season is determined by the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, a consortium of Ojibwe tribes.47 Indigenous approaches to wild rice management clash with the interests of the biotechnology industry and some university researchers over the genetic engineering of wild rice. The Ojibwe persist in taking responsibility for caring for manoomin, dedicated to the survival and integrity of a uniquely perfect grain that once sustained whole communities.