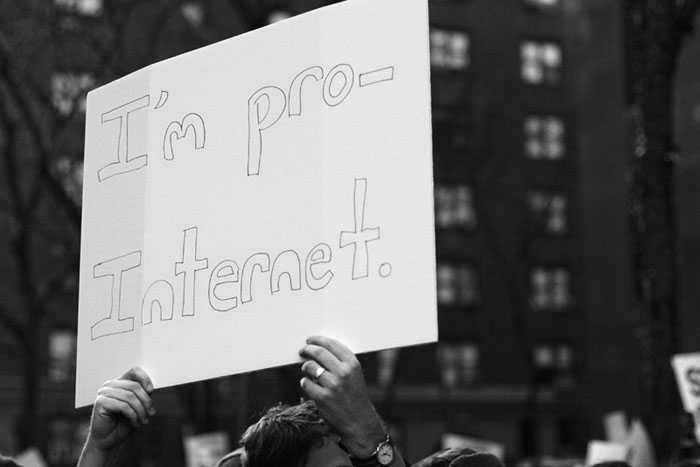

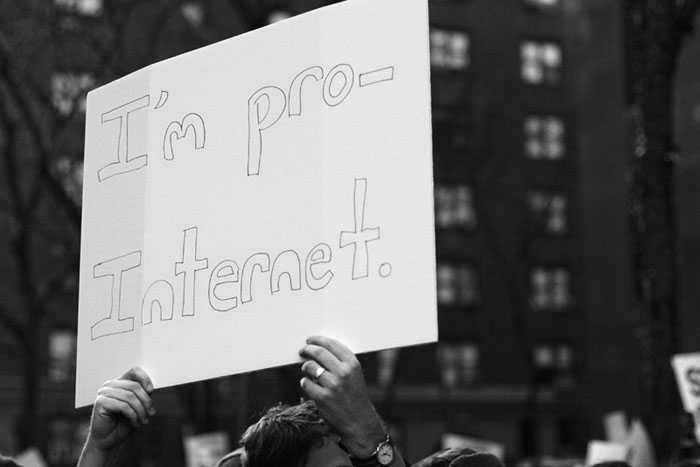

The SOPA/PIPA battles brought together a coalition that may be unprecedented in the diversity of viewpoints and backgrounds of its members. But those who came together shared in common that they could all say: “I’m pro-Internet” – This photo was taken at an emergency protest organized by the New York Tech Meetup community on January 18, 2012. Photo by Craig Cannon. http://www.meetup.com/ny-tech/photos/5468462/86976852/

Between the fall of 2010 and early 2012, untold millions of Americans urged lawmakers to protect the Internet and oppose the Stop Online Piracy Act and its predecessor and companion bills.

It’s quite possibly the largest single, directed form of (non-electoral) activism as far as number of American participants—and that’s fitting, as the legislation would have undermined the greatest facilitator of the democratic impulse that’s ever been known to humankind.

Together, we used the Internet to save the Internet, and registered a resounding victory against all apparent odds and in direct contradiction of the intuitions of the most seasoned establishment political actors and lobbies like the Chamber of Commerce and the Motion Picture Association of America. This is that story.

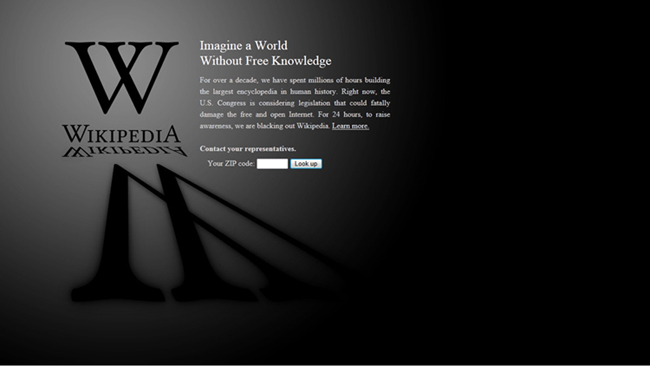

Most Americans are familiar with the extraordinary Internet Blackout of January 18th, 2012, but to get to that moment took months and years of toil by dedicated activists, online, in the streets, and in the halls of power. In an age of polarized partisan politics, it took an alliance between the far left, the far right, and countless concerned Americans whose proclivities span the vast spectrum in between. We looked past differences and came together to uphold values shared by the overwhelming majority of Americans—and people from around the globe, for that matter. In so doing, we cast a spotlight on much of what can still be good about our political processes, but also helped illuminate the underlying structural decrepitude that made it possible that politicians would blindly push legislation that so clearly controverted the will of so many of their constituents.

In order to win, the Internet would turn the SOPA/PIPA battle into a testing ground for activists’ tools, messages, and techniques—and all manner of viral satire, meme, and webcam ranting you could possibly imagine. Countless developers, websites, organizations, and even businesses tried to outdo each other in their activist creativity. But behind the scenes and beneath the seeming chaos of the public disruption, there were very real conversations happening between groups that do not usually play together. The “white shoe” lobbyists, the “white paper” policy advocates, technologists, venture capitalists, bloggers, and activists were in regular contact to discuss timing and strategy considerations. The participants in these dynamic coalitions often held wildly divergent viewpoints, but all shared an interest in defending Internet Freedom.

Essentially, anyone with a web presence (and who could therefore steer impressions to SOPA/PIPA content) could participate in the advocacy battle. It was decentralized, but it was organized, as we were actively trying to orchestrate a calculated mayhem.

Contained herein are essays written by dozens of people who were involved in those efforts. Authors of the essays that comprise Hacking Politics don’t necessarily endorse each other’s opinions—and, in fact, their opinions vary widely and often contradict one another. That’s precisely part of the point of this book: to demonstrate the ways in which people of distinct backgrounds, ideologies, and interests joined together in common cause to fight legislation that would’ve censored the Internet.

We don’t claim this to be a comprehensive accounting of everything that happened during the anti-SOPA/PIPA fight. Far from it. But it does represent the vantage points of an important group of activists who were invested in this fight for months or even years. The following pages are an account of their perspectives on the effort to beat SOPA/PIPA, and so necessarily elevate these viewpoints. Countless others who aren’t represented here also played critical roles in that fight, and surely have intriguing stories to tell as well. We are aware that this book is United States-centric. There’s critical work being undertaken in support of Internet freedom the world over, but we operate predominantly in the domestic sphere and that’s where the SOPA/PIPA fight was won, so it’s where we’ve focused. Would that we had the resources to engage more deeply with our brothers and sisters around the globe!

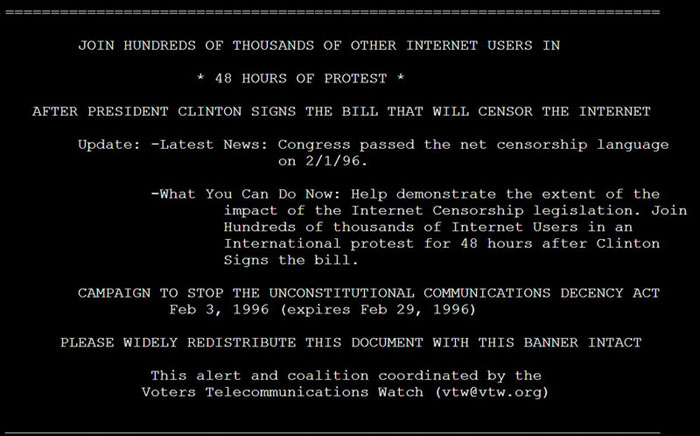

Demand Progress and Don’t Censor the Net—the organizations that the co-editors of this book help manage—are new groups without a longstanding institutional structure. We are well aware of the debts that we owe to longer-standing organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Public Knowledge, the Center for Democracy and Technology, Free Press, and others, as well as many key academics and myriad rank-and-file activists who care passionately about the issues at hand. Without their years (sometimes decades) of work, our organizations wouldn’t exist, and we wouldn’t have been able to play the roles we took over the course of this glorious effort. In fact, without the toil of so many conscientious groups and people, we’d surely have lost the fight for an open Internet long ago. We’re honored that many activists and organizations for whom we have so much respect have contributed essays to this book, though it’s impossible to do justice to their longstanding work over the course of just a few hundred pages. A stark indicator of the depth of the gratitude that we owe the longer-standing organizations: While most readers of this book will be well aware of the 2012 Internet Blackout, far fewer remember—and several were probably not yet alive for—the 1996 blackout to oppose the Communications Decency Act (which was later found to be unconstitutional).

Screenshot of the 1996 Internet blackout in opposition to the Communications Decency Act.

Screenshot of Wikipedia’s home page on January 18, 2012.

As we strive to be as inclusive as possible, and in the spirit of the creative chaos of the Internet, this book mashes up dozens of contributions into a coherent chronological narrative of the blow-by-blow of the anti-SOPA/PIPA organizing effort. It opens in the early fall of 2010, when the editors of this book joined the fray. We have also included what we hope are insightful analyses of what happened, from a variety of different vantage points. Some essayists were engaged in the anti-SOPA/PIPA cause for more than a year—and some were party to Internet freedom efforts for years before that—while others joined the fight in its waning days, even while playing critical roles therein. So there are necessarily some redundancies and some jumps forward and backward in time, but you’re smart enough to keep it all straight.

Some brief explanations of frequently-cited legislation:

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is a comprehensive copyright bill that Congress approved in 1998. References herein to the DMCA typically refer to the so-called “Safe Harbor” provisions that passed as part of the larger bill. The idea behind “Safe Harbor” is that a website or platform could let its users upload content, but not have to fear getting sued by copyright holders when their users posted unlicensed content. In exchange for this shield from liability, site operators must remove infringing content upon being alerted of its presence.

Prioritizing Resources and Organization for Intellectual Property Act (PRO-IP Act), passed by Congress in 2008, ten years after the DMCA. It is the PRO-IP Act that United States law enforcement agencies claim gives them power to seize domain names of sites registered in the U.S. and accused of facilitating intellectual property infringement. But the legality of the application of this power to the distribution of non-tangible property is disputed.

Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act (COICA), S.3804, was introduced by Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT) on September 20, 2010 but never became law. COICA would have allowed the government to seek court orders to shut down websites deemed to be “dedicated to infringing activities,” and would have forced Internet service providers (ISPs), domain name registrars, payment processors, and others to cease doing business with them. It would also have allowed for the creation of a “blacklist” of Internet domain names that the government alleged to be infringing, but for which it had not achieved such court orders. ISPs and others would be immune from any liability for blocking access to, or otherwise refusing to do business with, sites on this blacklist.

Commercial Felony Streaming Act (Ten Strikes), S.978, was introduced by Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) on May 12, 2011 but never became law. It would have made it a felony crime to engage in unauthorized streaming of copyrighted works for “commercial advantage or personal financial gain.” Those accused of streaming copyrighted works more than ten times would have faced jail time and stiff fines.

Preventing Real Online Threats to Economic Creativity and Theft of Intellectual Property Act (PIPA), S.968, was introduced by Senator Patrick Leahy on May 12, 2011 but never became law. PIPA essentially adopted the court order provisions of COICA, while dropping the blacklist of domain names outlined above. It was limited to the targeting of foreign sites (ie: those not registered with domestic domain names), but it was clear that many of its proponents yearned for legislation affecting U.S. domains too: They’d backed COICA, after all, and supported the PRO-IP domain seizures. PIPA also created the possibility that site operators would be prohibited from merely linking to disputed websites, and that search engines would be forced to remove these sites from users’ search results. The bill contained a much-debated provision requiring an “information location tool” to “remove or disable access to the Internet site” named in court orders.

Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), H.R. 3261, was introduced by Lamar Smith (R-TX) on October 26, 2011 but never became law. Like COICA and PIPA, SOPA would also have compelled ISPs, advertisers, payment processors, and “information location tools” (eg: search engines) to cease interaction with sites that were “dedicated to the theft of U.S. property.” SOPA’s provisions were thought to cover platforms for user-generated content—even if the platform’s owners harbored no intent to host infringing material, and even if they were unaware of said content. It was ostensibly targeted at foreign sites—bad enough in its own right—but COICA’s proponents had also targeted the domestic web, making clear their ultimate designs. Many feared that under SOPA domestic sites like search engines or social media platforms that merely linked to targeted foreign sites could also be penalized.