On June 22, 2011, I started Googling around to find contact information for the head of Google’s lobbying division, as well as for the person that designs the art for their search engine. I wanted to ask them to join in the disruption of public consciousness by placing a message about Internet censorship legislation on the homepage of Google.com. I finally found email addresses for Alan Davidson (Google’s head of lobbying at the time) and Ryan Germick—the man responsible for creating the art that Google rotates on its search engine page. See an excerpt from my email message to the Googlers below:

Our four hundred thousand members are primarily concerned with stopping PIPA and have sent over fifty thousand emails to Congress on the issue. Thousands have also called their senators to urge opposition to the bill. We now have agreement from a few Congressional offices to hold a staff briefing to highlight the various flaws of PIPA.

Meanwhile, we’ve been reaching out to dozens of groups to generate additional opposition to the bill (see attached list). We’ve made inroads with seniors’ groups on prescription drug issues in PIPA, as well as right wing groups concerned with the speech implications.

Even with all this, it seems we are lacking broad public awareness (and the resulting fear from members of Congress). But we were realizing that you at Google are sitting on perhaps the world’s greatest pedestal, given your massive presence on the web.

Would you be willing to use your rotating Google search engine art to highlight the free speech implications of what Congress is about to do?

By the fall of 2011, as the coalition of groups working with us on this campaign began to mushroom, I had begun dreaming of the advocacy possibilities latent in pushing websites under attack to draw their visitors’ attention toward the legislative fight in Congress. On November 14, 2011, I emailed a message to our coalition partners asking the following question by email:

Will a time come when the private sector net firms/sites will be willing to mobilize their user/customer bases for constituent contacts? I would just point out that the airline industry does this fairly regularly now … witness ie: United and other companies mobilizing their email lists to send in comments to the FAA re: new desired airline routes (ie: when a direct to Beijing line opened) …

I can only imagine the impact of Google, for example, changing its search engine art to a SOPA/PIPA-related image—one can only dream. :)

It took months of additional work by our coalition of Internet Freedom fighters, but my mouth still dropped on January 18, 2012 as the following image appeared on Google’s homepage:

Thousands of websites across the Internet “blacked out” and staged online protests to raise public consciousness about the dangers of SOPA/PIPA. In response, I emailed my colleague David Segal the following message: “ha. 2 months later it’s a new day. my god.” It was indeed a new day, and perhaps more than we are still able to grasp. It was the final dramatic action in a campaign that took a year and a half.

Though the downward slide of SOPA/PIPA had been well in progress for months, by January 18, 2012 it was impossible even for the bills’ proponents to deny that they were dead. Epic win. Ironically, throughout much of this process, Demand Progress was accused of being puppets of Google. But this email chain hopefully debunks the idea that Google owned or served as puppet-master of the anti-SOPA/PIPA coalition. In fact, for many months it felt like we were trying to draft them into our guerilla battles. Indeed, this fight was much bigger than Google or any one company or website.

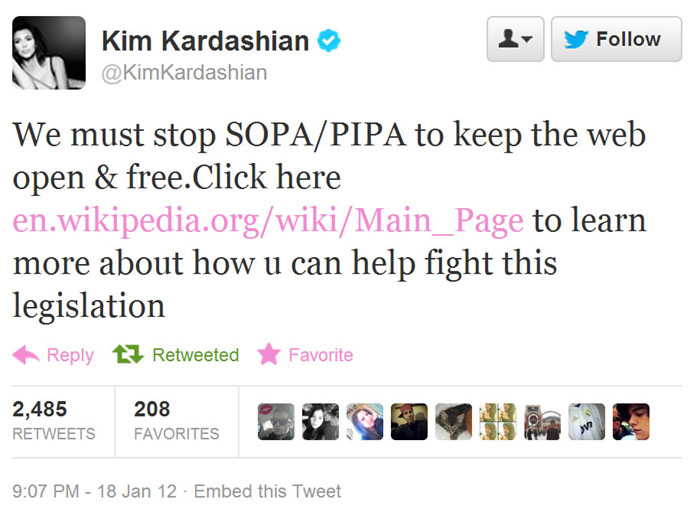

Proof? Even Kim Kardashian got in on the action. On the evening of January 18, 2012, the celebrity most famous for being famous tweeted the following warning to her millions of followers: “We must stop SOPA/PIPA to keep the web open & free.”

SOPA/PIPA activism had itself become a meta-meme, and all of sudden two bills that had been virtually ignored for months were being discussed everywhere.

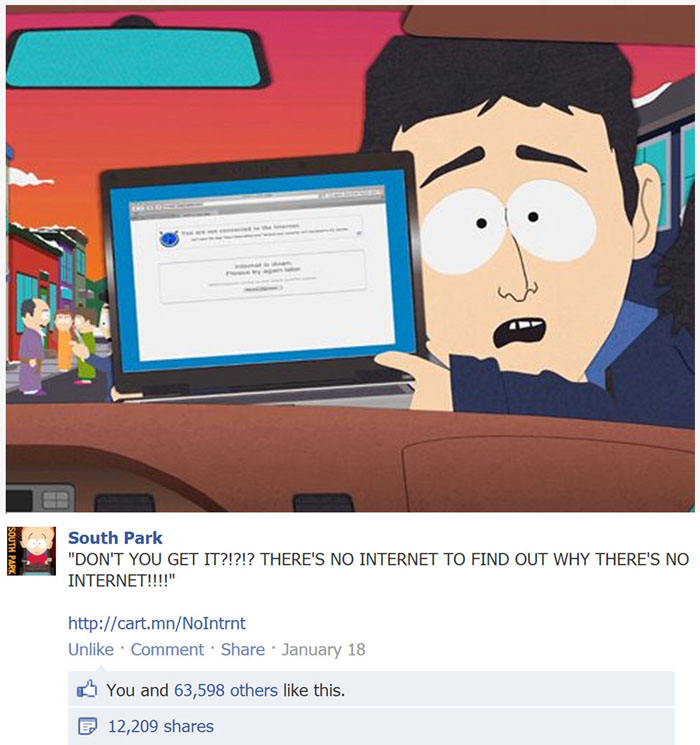

South Park weighed in on the SOPA/PIPA battle with this image on its Facebook page on January 18, 2012.

The epic downfall of SOPA & PIPA was a turning point in the Internet’s political coming of age story, but it was a critical moment not because a celebrity (or many celebrities as was the case) swooped in and blessed the rebels. Indeed, before mid-January, Kardashian’s opposition to SOPA/PIPA had already been preceded by celebrity alerts from actors Ashton Kutcher and Olivia Wilde, filmmaker Kevin Smith, musician Trent Reznor and numerous other creators.

Pornhub.com joined in the American Censorship Day protests by placing a link on the site’s homepage.

What made the participation of celebrities like Kim Kardashian notable, was not actually their fame. It was that on January 18th and the days that followed, many celebrities reacted like the rest of us did when they found out about SOPA. Like millions of others, Kim Kardashian simply recognized her own identity as an Internet user and drew a very public line in the sand (well, we can at least say that of the person who manages Kardashian’s Twitter account). In fact, Congressional staffers later reported that the SOPA/PIPA battle had been the impetus for as many constituent contacts as any issue in memory—including recently contentious issues like health care and immigration. Somehow a bill related to DNS blocking rose to a similar level of public prominence—for at least a brief moment—but while Americans were sharply divided when it came to health care and immigration reform, they were overwhelmingly united in favor of the Internet.

It was a political coming of age: the Internet had truly arrived in Washington. In the weeks leading up to the blackout, most lawmakers were treated to decentralized barrages of hundreds of emails and phone calls about SOPA/PIPA. Their social media pages were filled with inquiries about the two bills from incredulous Netizens. Twitter announced that in the first 16 hours alone on January 18th, over 2.4 million users tweeted about SOPA/PIPA. Meanwhile, programmers and web developers were connecting online to coordinate visits with lawmakers, while in New York a tech meet-up group anchored a rally that saw thousands of protestors gather outside the offices of their senators. Along the way, coders interested in the effort went to work programming new contact tools for constituents, and witty individuals took to sites like YouTube and Facebook to launch viral alerts and satirical memes about SOPA/PIPA. Some bill sponsors like SOPA-backer Rep. Lamar Smith were particularly vilified by Internet humorists (some clever, some not).

In short, Internet users harnessed the very platforms endangered by the bills to spread knowledge of the legislative threat—and they brought the creative energy of dozens of web-savvy individuals to find ways to cut through the clutter. Above all else, these digital activists—whether experienced warriors or newbie agitators—seemed stunned that Congress could look at the same facts that they had and come to the impossible conclusion that the Internet deserved to be restricted and censored. Their very persistence in opposing legislation that conventional wisdom declared headed for passage proved that in a way, ignorance of Washington’s game logic allowed the rebels to achieve an outcome that many saw as unrealistic. The Internet had overcome party leaders and committee chairs, and violated norms of seniority and power in the course of defeating SOPA/PIPA.

As Kim Kardashian herself demonstrated, Internet users around the world put on their tricorn hats and went Paul Revere on the political establishment. But where the Arab Spring protests had used the Internet to take down governments, the SOPA/PIPA battles used the Internet to defend the Internet itself. After waves of public outcry, the bills were declared dead, and the politics of the Internet in the United States have not been the same since. Weeks after the legislative defeat, Democratic Rep. Jared Polis told reporters at Politico that the successful opposition was evidence of a “coming of political age.” Republican Rep. Jason Chaffetz further commented, “Nobody wants another SOPA moment … The nerds are more powerful than anyone thought.” Both lawmakers opposed SOPA/PIPA and have since seen the shifts in mindset from their colleagues.

In spite of the spectacularly public way in which SOPA/PIPA was defeated, many backers of the legislation appear confused or in denial about how this came to be. Instead of recognizing that the integration of the Internet into the lives of almost every American has led the emergence of a powerful new constituency for Internet freedom, some politicos spent the days following the SOPA/PIPA defeat bowing down to Google and congratulating the company’s lobbyists for successfully misinforming the public.

Filmmaker David Newhoff, for example, published a January 18th op-ed in The Hill where he took the view that tech companies manipulated the opinions of their users: “Silicon Valley’s fear campaign has worked its magic … If SOPA and PIPA are defeated not because of legal merit but because of a desire to throw off the shackles of a media oligopoly, we will only have donned the shackles of the tech oligopoly who scared us into doing their political bidding.” In this version of the story—and it was shared by a surprising number of people—the defeat of SOPA/PIPA was overwhelmingly driven by (specious) propaganda purveyed by Big Internet companies like Google. These observers had squeezed and contorted the effort to make it fit into the standard Washington paradigm: it was but another sandbox war between rival industries.

The persistence of these misinformed views keeps me hoping that Hacking Politics helps demonstrate just how emergent and grassroots the outcry really was. Setting the record straight is not just a matter for the history books; it is critical to ensuring that in the future Congress charts a sensible course for the Internet. Otherwise, SOPA/PIPA backers who believe that Google was responsible for their defeat will simply assume that they can negotiate with a single company to prevent problems in the future. To be fair, Google had a large presence during the Congressional debates over SOPA/PIPA, but to credit them for the win would be missing the biggest lesson—specifically, that the perspectives of Internet users now demanded a seat at the table. In fact, U.S. Senator Ron Wyden—who in the early days of the fight practically stood alone in opposition to PIPA—reflected that the citizen outpouring “was not something that anybody could have dreamed up. This was organic.” For Wyden, the successful citizen defense of the Internet was not something that hired guns could have staged and was instead evidence of potential new policymaking dynamics.

At a gathering of SOPA/PIPA opponents after the bills were defeated, Wyden quipped that his colleagues “practically had me in a corner with a dunce hat.” But that when all was said and done, he saw an example of an “extraordinarily powerful antidote to all the frustration” with Washington. What Wyden could see—and that most of his colleagues could not—was that together millions of Americans had effectively come up with a hack around Congress’ otherwise unaccountable policy process. Indeed, the story of how the SOPA and PIPA bills were defeated is really a rallying call for anyone searching for signs of hope in our political system