Yochai Benkler is the Berkman Professor of Entrepreneurial Legal Studies at Harvard, and faculty co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society. Since the 1990s he has played a part in characterizing the role of information commons and decentralized collaboration to Innovation, information production, and freedom in the networked economy and society. His work can be freely accessed at benkler.org. This essay is adapted from a broader study of SOPA activism.

In the days following the defeat of SOPA and PIPA, two conflicting narratives developed to describe the events. The politics-as-usual narrative interpreted the events as “Google and Facebook have come to town”; the new major industry players had become new players in the same old lobbying game. The more radical narrative was that the networked public sphere had come into its own; that the events reflected a new model of political organization and democratic participation. The game itself had changed, not merely its players.

We set out to try to understand which narrative contained more truth by using a platform we developed, Media Cloud, that allows us to map the evolution of a public controversy by collecting time slices of thousands of sources, and using text and link analysis to map the progress of the debate over time. We map who is saying what, and who is citing whom, at what point in the emerging public conversation. What emerged from our study of over ten thousand articles, web pages, and blog posts that discussed SOPA, PIPA, or COICA over a period of eighteen months was a map that supports the proposition that what we had seen was quite a different game from what we had seen in the traditional, massmediated public sphere.

A diverse network of actors, for-profit and non-profit, media and nonmedia, individuals and collectives, left, right, and politically agnostic, had come together. They fundamentally shifted the frame of the debate; experimented with diverse approaches and strategies of communication and action; and ultimately blocked legislation that had started life as a bi-partisan, lobby-backed, legislative juggernaut. While it is certainly possible that behind-the-scenes maneuvering was more important and not susceptible to capture by our methods, what is clear is that by ProPublica’s tally, before January 18, 2012 SOPA/ PIPA had 80 publicly declared supporters and 31 opponents, but by the next day the bills had 65 supporters and 101 opponents.

The January 18th online protest campaign and its anchor, the Wikipedia blackout, were the core interventions that blocked the acts. But our study suggests that that day’s events cannot be understood in terms of lobbying or back room deals; rather, this outcome represents the fruits of the online discourse and campaign whose participants are so many of the authors of this volume.

Our approach focuses on mapping the public online portion of the networked public sphere. We combine three core elements. First, we understand the relevant communicative sphere not in terms of a stable, broad category of sites that are “blogosphere” or “political blogs,” but rather in terms of discrete “controversies.” By “controversy” we mean a set of communications and actions around a core set of connected issues, irrespective of whether they originate in blogs or mainstream media, websites or even the customer-service discussion boards of gaming companies.

Controversies have linguistic markers, a temporal dimension, and a political-economy valence or potential outcome. We use textual cues, here SOPA, PIPA, and COICA, as ways of filtering a broader range of blogs, online media, organizational and personal sites to draw in sites that addressed the controversy. Second, we emphasize the time dimension. We understand controversies as having a beginning, an end, and internal dynamics that can shift and change in ways that are revealing. Temporally-sensitive tools offer better insights into the shape of influence, framing, and action than do tools that capture broad, time-independent states. As a result, we find a public sphere that is more diverse and dynamic than has generally been portrayed by prior computationally-instantiated analyses of the networked public sphere. Third, we combine the text and link analysis with detailed human analysis, including interviews, desk research, and coding, particularly around highly-visible stories and sites that emerge as significant from the network analysis.

This allows us to typify the phenomena we observe in the data in terms of the unfolding political economy and the discursive structure of the controversy over time. In this, our work preserves a bit more of the richness and complexity of historical and sociological analysis of social movements, using computation to create a corpus of objective data guiding our selection of particular interventions and organizations for more detailed analysis, and highlighting relations among sites and interventions at given moments over the course of the controversy.

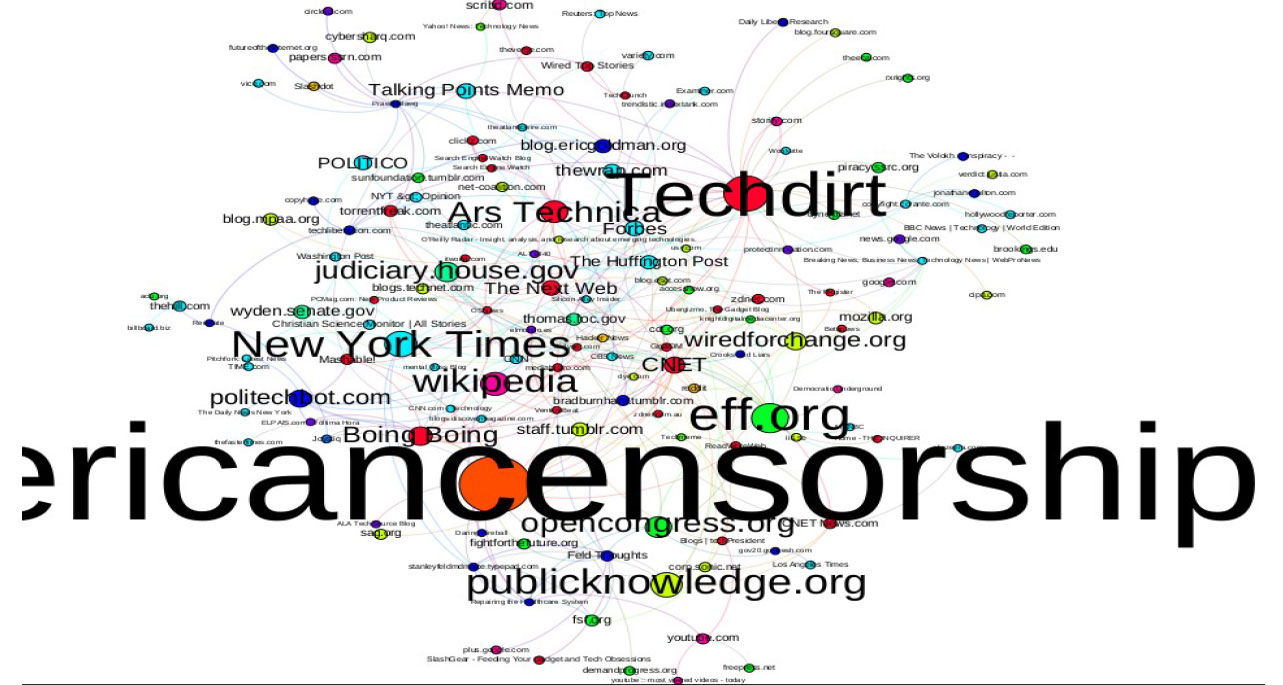

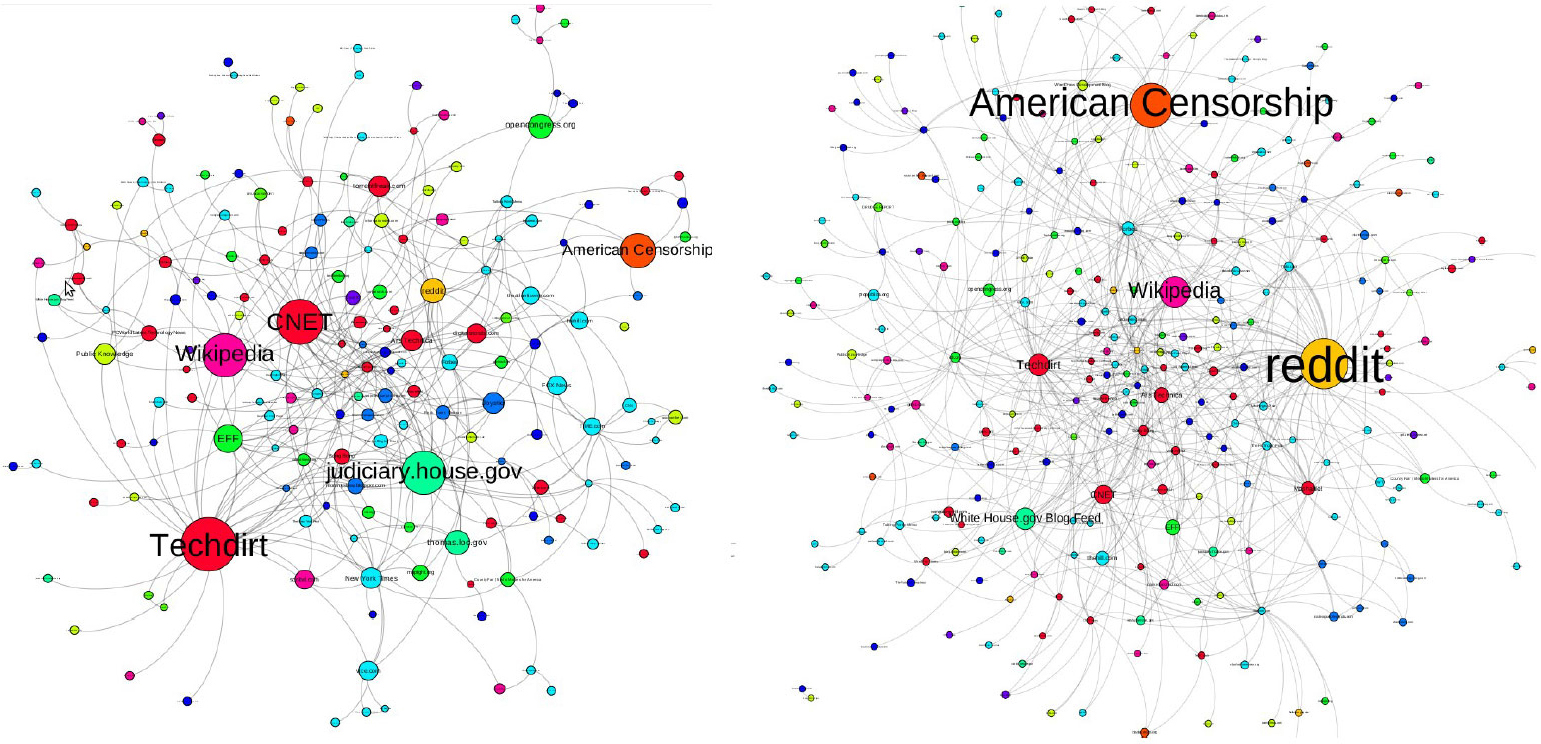

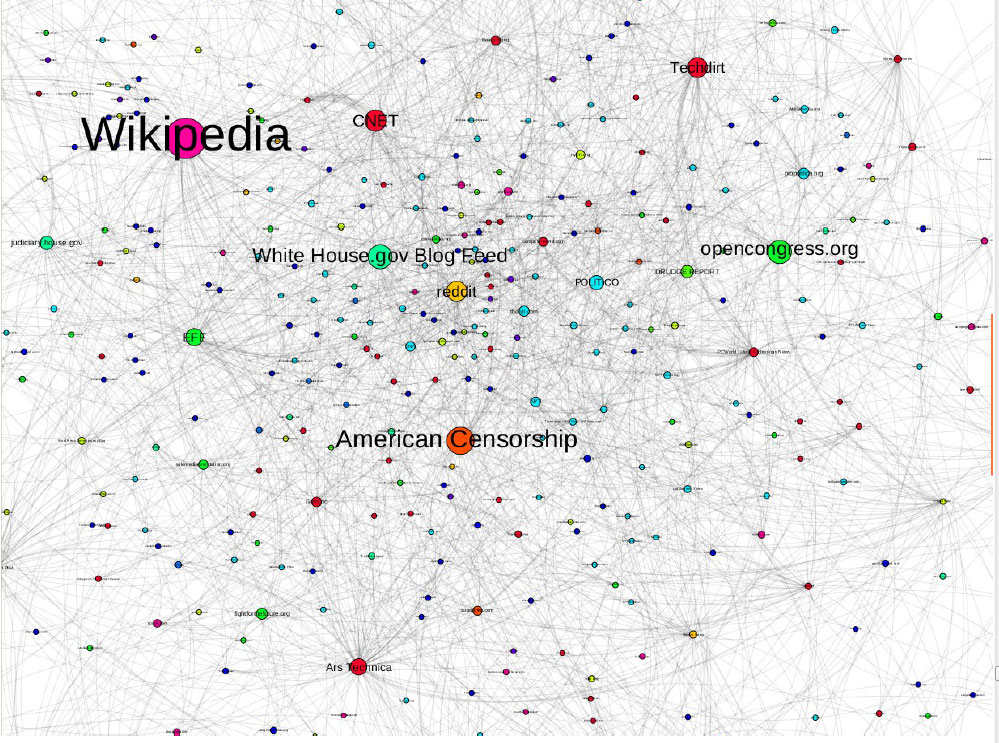

The following narrative and maps present the storyline of the seventy months between the introduction of COICA in September of 2010 and the defeat of PIPA in January of 2012. The data are 10,456 stories from one thousand three hundred seventy-nine distinct sites that mentioned one or more of the bills during that period. The maps represent the stories published each week. The size of each node reflects the number of other nodes active during that week that linked to the node, giving us an initial observation of who was a highly-linked node during that week. Node colors represent media type; we identify 11 different media types.

Consistent with most prior work on the blogosphere, we treat links as evidence of attention. The location of the node provides a measure of how close any two nodes are based on how many other nodes link to both nodes during that period. We treat such nodes as related in attention. The use of the maps reflects our sense that attention is time-dependent, not constant over long periods, and that a highly-linked node at time t1 will be influential on everyone at that time, even if that particular node is barely noticeable from the perspective of a full 18 month period. It allows us to capture who set the agenda in any given week, so that when that agenda is then taken up by later nodes we can still observe the origins of an intervention. Our approach suffers several obvious lacunae. We do not analyze Facebook or Twitter data; nor do we cover mailing lists, IRC, or simple email. All these likely played a large role. Nonetheless, our approach captures a larger ratio of the diverse sources operating in a defined controversy than prior studies have generally sought to analyze.

We coded 11 media types, with nodes colored as indicated below. The numbers that follow refer to the respective [r,g,b] value, and color names are descriptive. Listed in alphabetical order, these media types are: (1) Blogger(s): blue, [0,0,255]; (2) Gaming Site: azure blue, [0,119,255]; (3) General Online News Media: light blue, [0,238,255]; (4) Government: sea green, [0,255,153]; (5) Independent Group: lime green, [0,255,38]; (6) News Aggregator: chartreuse, [81,255,0]; (7) Private Sector: yellow green, [200,255,0]; (8) Tech Media: red, [255,0,43]; (9) Social Linking Site: light orange, [255,196,0]; (10) SOPA/PIPA/ COICA-Specific Campaign: orange, [255,77,0]; (11) User-Generated Content Platform, Networking Site, or Internet Tool: pink, [255,0,157].

We identify nine core findings from our analysis.

First, the networked public sphere is much more dynamic than previously observed. In any given week or month, a major node like Wikipedia may be secondary, while an otherwise minor node, such as the blog of a law professor commenting on an amendment or a technical paper on DNS security, may be more important. The dynamic nature of attention in controversies over time means that prior claims regarding a re-concentration of the ability to shape discourse miss important major fluctuations in influence and visibility. Perspective, opinions, and actions are developed and undertaken over time. Fluctuations in attention given progressive development of arguments and frames over time, allow for greater diversity of opportunity to participate in setting and changing the agenda early in the debate compared to the prevailing understanding of the power law structure of attention in the blogosphere. It also likely provides more pathways for participation than were available in the mass-mediated public sphere.

Second, individuals play a much larger role than was feasible for all but a handful of major mainstream media in the past. A single post on reddit, by one user, launched the GoDaddy boycott; this is the clearest example in our narrative. But we also see individuals embedded in what would in the past have been peripheral organizations playing a role in ways that would have been historically impossible. Notably, Mike Masnick of Techdirt became the single most important professional media site over the entire period, overshadowing the more established media. Individual blogs by academics were able to rise at various moments, like the visible role that law professor Eric Goldman’s blog posts played in early December 2011, when the manager’s amendment to SOPA came out and the OPEN Act was introduced.

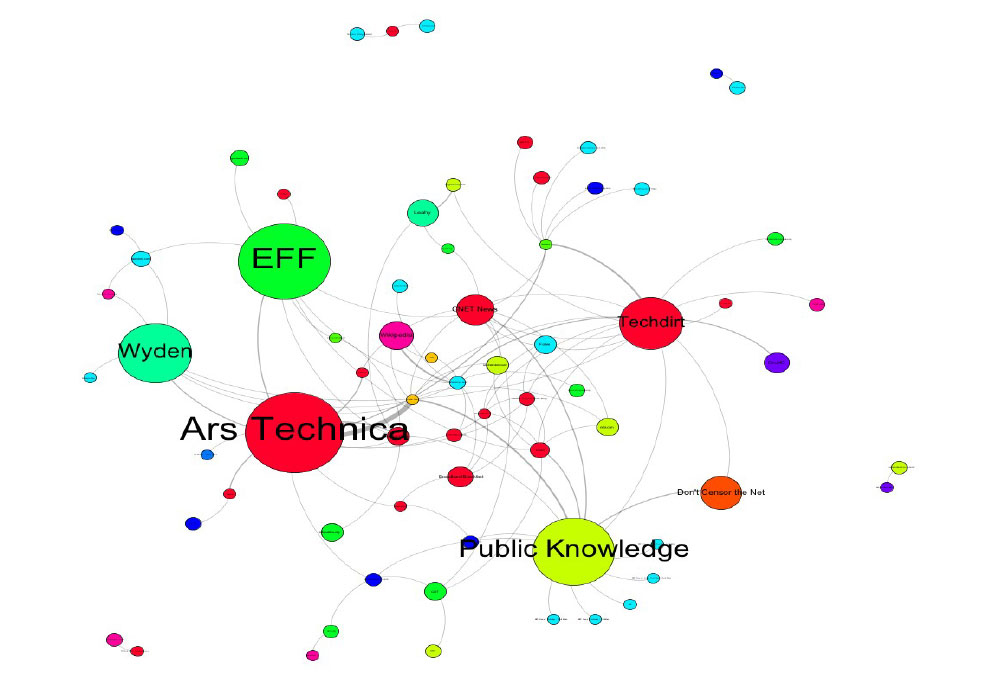

Third, traditional non-governmental organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Public Knowledge played a critical role as information centers and as core amplifiers in the attention backbone (below) that transmits the voices of various, more peripheral players to the wider community.

On several occasions various letters would be written by experts, and then posted and amplified by the EFF or Public Knowledge. These organizations also played a critical role in informing the network about changes and upcoming legislative events.

Fourth, widespread experimentation of new and special-purpose sites played a critical role in converting discussion into action. Several different organizations and individuals experimented with dozens of special-purpose sites and mobilization drives, some of which were indeed successful in garnering attention and converting it to action, emails or phone calls to Congress, the symbolic strike of January 18, 2012, or consumer boycotts. Among these, Demand Progress was an early player against COICA, Dontcensorthenet played a large role around the introduction of PIPA, and Fight for the Future emerged as a force around the introduction of SOPA; each of these players instituted successful efforts prior to the ultimate Wikipedia boycott. Similarly, the reddit boycott on GoDaddy was a transformative moment in the campaign over corporate support or opposition to the bill. The widespread experimentation in these sites was their critical feature. It replicated with regard to online mobilization the same kind of innovation model we have seen for Internet innovation more generally: rapid experimentation and prototyping, cheap failure, adaptation, and ultimately rapid adoption of successful models.

Fifth, highly visible sites within the controversy cluster were able to provide an attention backbone for less visible sites or speakers, overcoming the widely perceived effect of “power law” distribution of links. Fight for the Future benefited from links from more established sites, like the Mozilla front page. The phenomenon was not limited, however, to the largest emerging sites, but was available for more discrete interventions as well. Julian Sanchez of the Cato Institute, for example, authored a careful critique of the oft-repeated but poorly founded claim that piracy cost the copyright industries fifty-eight billion dollars a year. Cato itself did not receive a very substantial number of links, but was sufficiently visible within the link economy for Techdirt to link to it, and the Techdirt story was, in turn, linked to by both reddit and the EFF, further amplifying this critique. Sometimes amplification is direct—a top site links directly to an initial intervention. Sometimes an intervention can be transported to larger audiences over a series of amplification hops of increasing visibility. This dynamic, interventions that get noticed by increasingly more visible sites, and are then themselves amplified by yet-more visible sites, is what we call an “attention backbone.”

Sixth, at least on questions of intellectual property, the long-decried fragmentation and polarization of the Net was nowhere to be seen. Political activism crossed the left-right divide throughout the period; the opposition was every bit as bipartisan as was congressional support. Demand Progress and Dontcensorthenet are the two most obvious nodes in this bipartisan effort, but we also see more traditional left and right political blogs, like DailyKos and HotAir, joining in the fight on the same side.

Seventh, subject area, professional media, in this case tech media, played a much larger role in shaping the political debate than the traditional major outlets. Techdirt, CNET, Arstechnica, and Wired carried the burden of media coverage throughout the period.

Eighth, consumer boycotts and pressure played a role in shaping business support and opposition. The two most visible instances were the reddit boycott on GoDaddy and the pressure gamers put on game companies to oppose SOPA/ PIPA, which bore fruit in the last six weeks of 2011.

Ninth, the network was highly effective at mobilizing and amplifying expertise to produce a counter-narrative to the one provided by proponents of the law. Technologists, law professors, and entrepreneurs emerged at various stages of the controversy to challenge proponents and make expert assertions that went to the core of the debate: the meaning of changes in various drafts; the effects of the laws on DNS security or innovation, or the constitutionality of the bills.

The Combating Online Infringements and Counterfeits Act (COICA) was introduced in September 2010. A September 20, 2010 report in The Hill framed the bill as an uncontroversial, bi-partisan effort, spearheaded by Senators Leahy (D-VT) and Hatch (R-UT) and backed by all major industries involved and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Senator Leahy stated that “Protecting intellectual property is not uniquely a Democratic or Republican priority—it is a bipartisan priority.”

The basic framing that this new law would save millions of jobs and billions of dollars and had broad bipartisan support remained the core narrative of proponents over the following year and a half. The counter-narrative that drove the major Internet protests of January 18, 2012 and ultimate abandonment of the statutes began to emerge almost immediately. Its progression suggests a more dynamic, diverse, and decentralized networked public sphere than was true of the mass mediated public sphere or has been described in prior computationally-instantiated descriptions of its shape and structure.

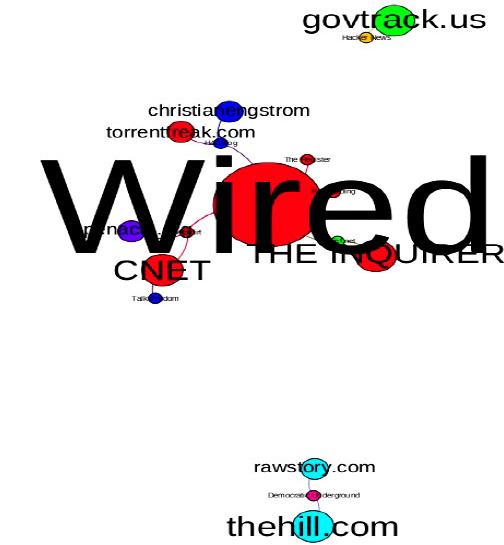

The first fortnight after the introduction of COICA consisted of a two-stage pump. Traditional media paid no attention to the law, with the exception of The Hill’s single story. The alarm was raised by West Coast tech media, in particular CNET and Wired, which were the first sites to report on COICA critically on September 20, 2010, and Techdirt, which linked to both stories and framed them in terms of threat. By the following week, however, action had shifted from tech media to NGOs, most prominently the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the left-leaning Demand Progress. We do, however, also see efforts by industry—in this case CE.org, the consumer electronics industry, opposing the bill. In this second week, EFF plays two roles that it will sustain during this first wave of the controversy. First, it provides an information clearinghouse about what is happening in the legislative arena. And second, it plays a role that others like Public Knowledge or Techdirt play in future iterations of the debate: it amplifies peripheral voices and makes them visible throughout the (still small) network engaged in the controversy. In this case, EFF is amplifying a letter by eighty-seven Internet engineers who wrote to the Senate Judiciary committee that the legislation “will risk fragmenting the Internet’s global domain name system (DNS), create an environment of tremendous fear and uncertainty for technological innovation, and seriously harm the credibility of the United States in its role as a steward of key Internet infrastructure.” By posting this letter on a site of major visibility, the EFF here, and others later, essentially create an attention backbone, along which an otherwise peripheral intervention can travel to the attention of many more participants than the initial speakers could have reached given the visibility of whatever outlets are directly under their control.

Week 1

Week 2

Demand Progress, by contrast, begins to lead during this period the translation of online outrage into political action by initiating a petition drive that ultimately collects over three hundred thousand signatures. This model of translating online debate into congress-focused communications will, of course, become a core force of the efforts to block the laws.

Little occurs in October, but mid-November, as the Senate Judiciary Committee considers and approves COICA, sees a burst of activity. Several features are notable. First, while the Fox News, the Los Angeles Times, and other mainstream media outlets begin to take notice, online tech media continue to anchor the flow of information within the controversy. Second, Public Knowledge joins EFF, and begins to take on both the information clearinghouse and attention backbone amplifier roles, roles that it will later play to a much greater degree.

Most dramatically, however, we see the right wing of the blogosphere taking up the resistance to COICA, and we see the left-right coalition online that continues to typify the entire controversy emerge very clearly. In the detail of the map from November, we see a range of libertarian blogs and organizations, like Cato, Atlas Shrugs, or Techfreedom, and the core blogs in the right wing of the general political blogosphere, such Hot Air, Instapundit, and Red State. This emergence of the right wing resistance is initiated by Patrick Ruffini of Engage LLC, a consultancy that specializes in building online campaigns for the political right, which also launches Dontcensorthenet. Ruffini continued to collaborate with David Moon and David Segal of the left-leaning Demand Progress throughout the campaign. Interestingly, the focal point for the right wing was not the Senate’s action on COICA, but the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Operation In Our Sites, an allegedly anti-piracy operation which involved extensive seizure of domain names and was seen as sweeping too broadly and aggressively that brought home to liberterians and the right-wing more generally the threat created by COICA.

November 2010, detail.

In late November 2010, Senator Wyden blocked lame duck passage of COICA, setting the stage for the reemergence of the controversy in the Spring of 2011, when Senator Leahy introduced the successor bill, PROTECT-IP, or PIPA.

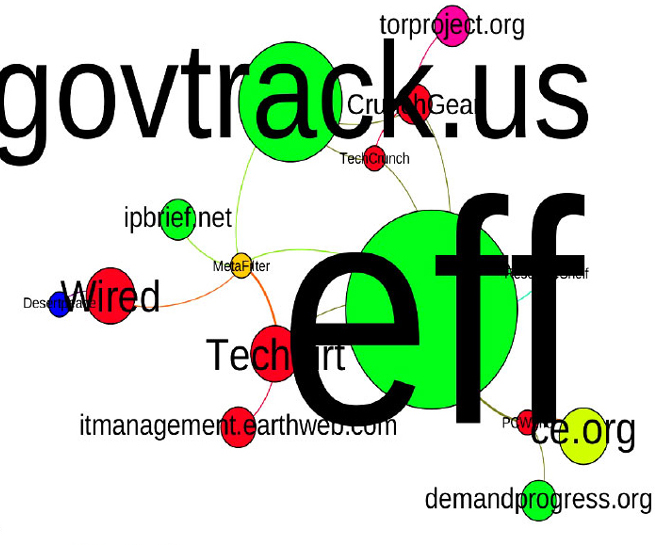

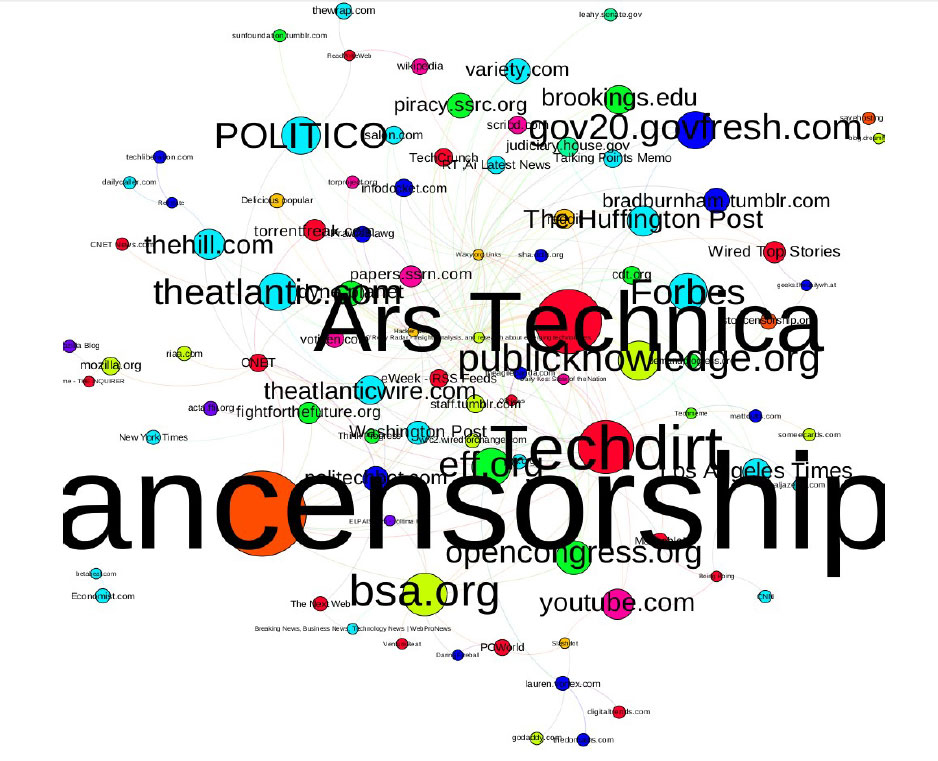

Phase II: PIPA, May 2011

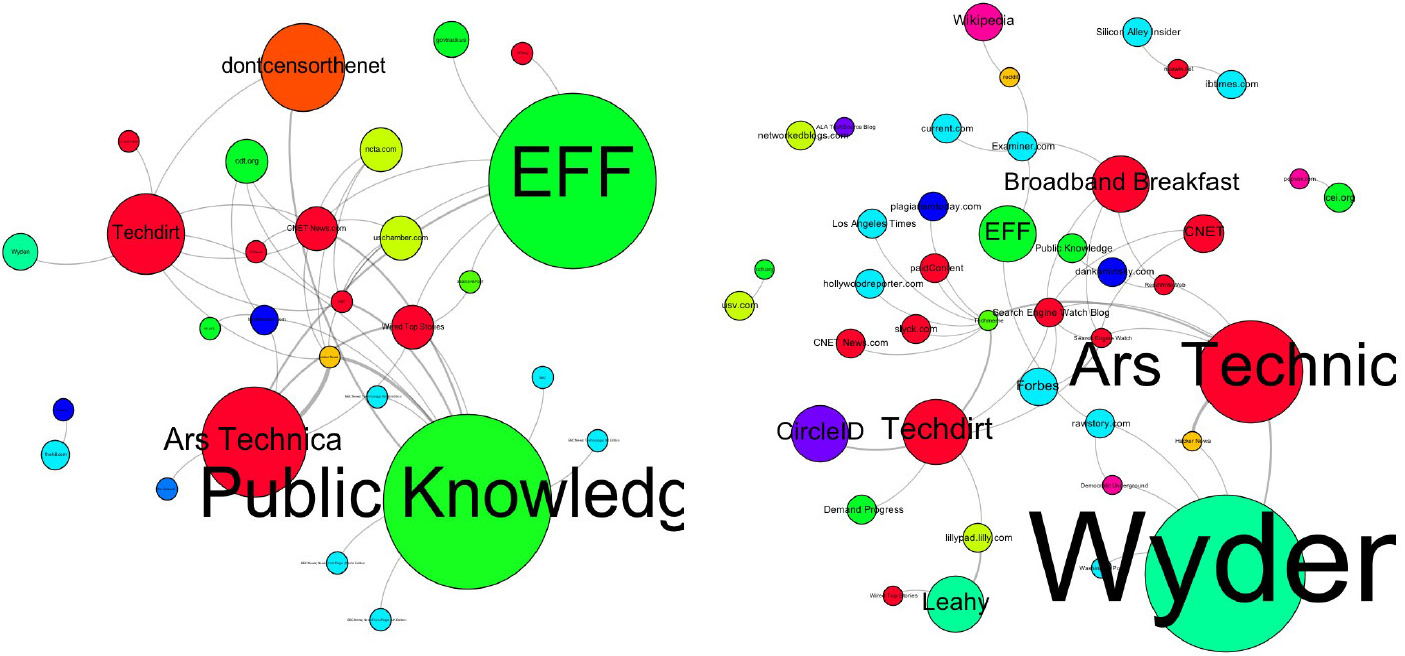

Looking at the entire month of May 2011, we see four major elements. The tech media, with Ars Technica partly replacing Wired and CNET alongside Techdirt; Public Knowledge and EFF share subject-area NGO leadership; special-purpose online campaign, here most prominently the Dontcensorthenet online petition, similar to the Fall of 2010 drive by Demand Progress; and Senator Ron Wyden’s own announcement that he is placing a hold on PIPA but may not be able to stop the flood, which raises the alarm more generally.

When we break May down into before and after Senator Wyden’s hold, we see very clearly that the NGOs and online campaign play a core role in the lead up to Wyden’s placing the hold, and then tech media take the role of disseminating and amplifying Wyden’s action after the fact.

Week 2, Week 3 May 2011

At that point traditional media do begin to pay attention; for, example, the Washington Post and the LA Times appear, but online these major news sites play a relatively small role. The larger visibility of Forbes in the third week owes to a single online opinion piece by Larry Downes, a highly articulate critic of PIPA.

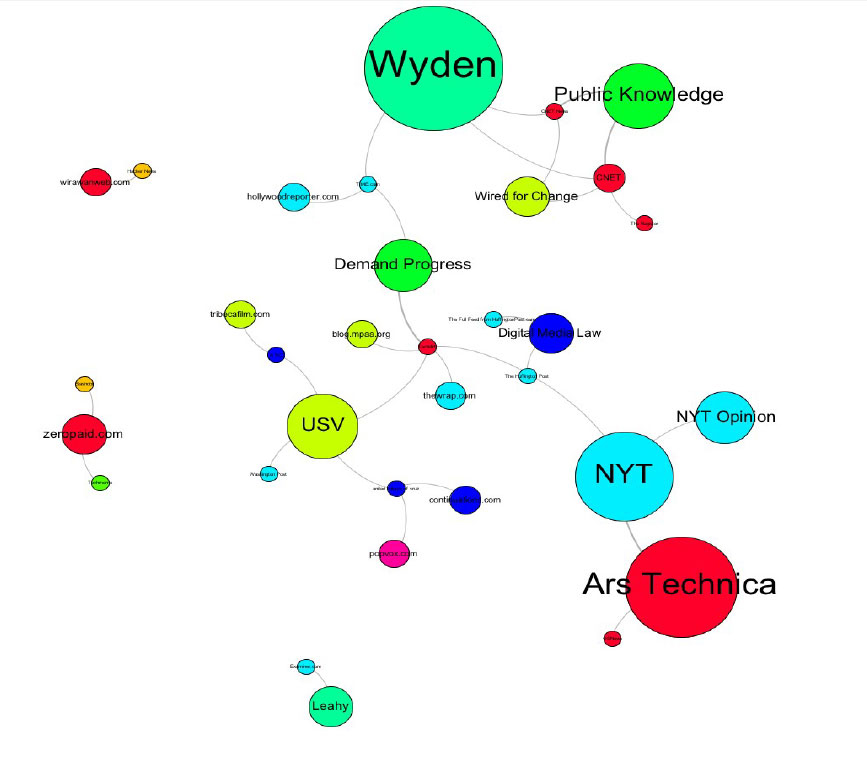

June 2011 still sees some of the same voices and dynamics already described continue; we note here only significant new observations. First, we see for the first time that a June 8 New York Times editorial plays a significant role in the conversation. Second, while in May it was the right-of-center petition drive, Dontcensorthenet, that was growing, in June Demand Progress is highly visible. The collaboration between the two groups continues. Third, we see that Union Square Ventures, and its principals Brad Burnham and Fred Wilson as individuals, organizes a letter from venture capitalists explaining how PIPA would endanger innovation on the Net. Finally we see here, as we see elsewhere during this period, that efforts by industry-side interventions, while successful in getting on the editorial pages of the LA Times and other media, do not seem to thrive in the online environment.

Here, Digital Media Law is an effort by the screen actors’ guild to support the law; and while it is linked to by the Huffington Post, it does not link to the rest of the conversation.

Phase III: SOPA

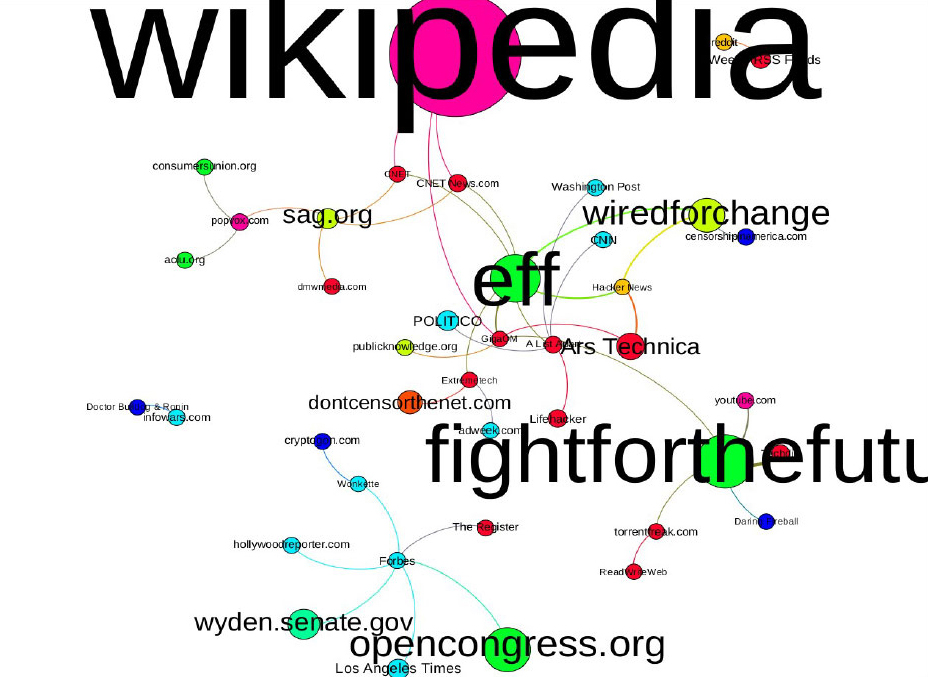

After a summer lull, Congress returned to the arena with the introduction of SOPA in the House on October 26, 2011. The three most important “newcomers” to the maps during these weeks are Wikipedia, Fight for the Future, and Open Congress. Wikipedia at this stage plays a purely information role. The protest that would emerge almost three months later had not yet been hatched, and our analysis of which parts of Wikipedia are being linked to over this period makes it clear that links to Wikipedia are informational: they are links to the articles on SOPA and PIPA, not to mobilization on talk pages. Fight for the Future (FFTF) and Open Congress, co-founded by Tiffiniy Cheng and Holmes Wilson, come to play a central role from here to the end of the campaign. Here, FFTF marks the first major successful use of video in the anti-SOPA/PIPA campaign, presenting a video informational polemic with a point of action to contact legislators. Open Congress offers a complementary model of access to the written materials on the Act, again, with a point of contact and an ability to “vote” publicly on the bill. The screen actors’ guild (SAG) is active, but does not garner as much attention.

Week of October 24, 2011

October 31-November 7, 2011

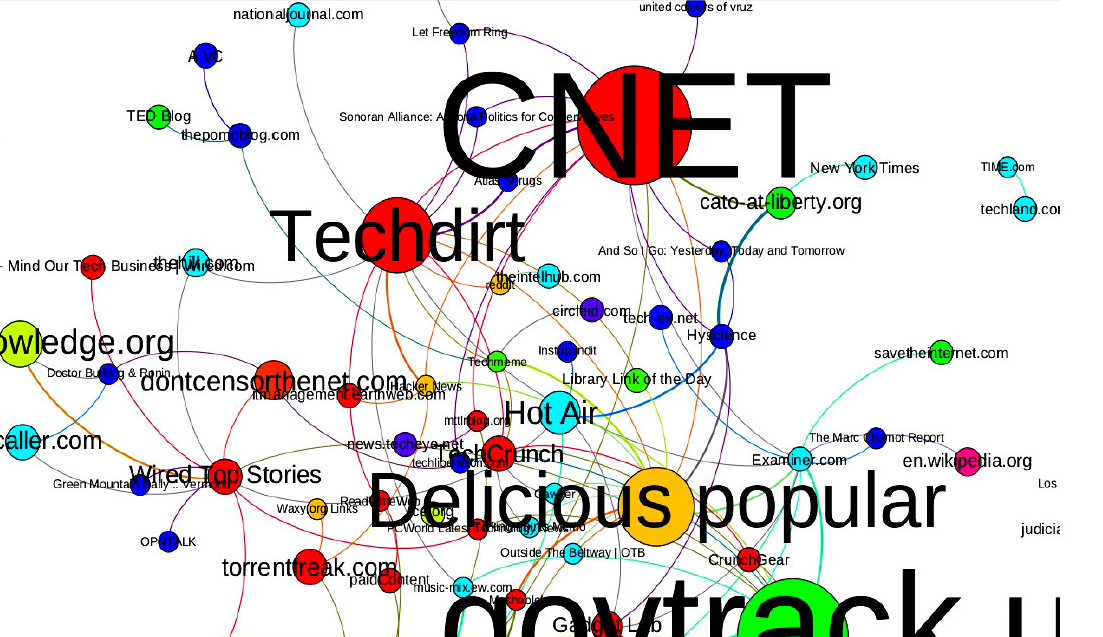

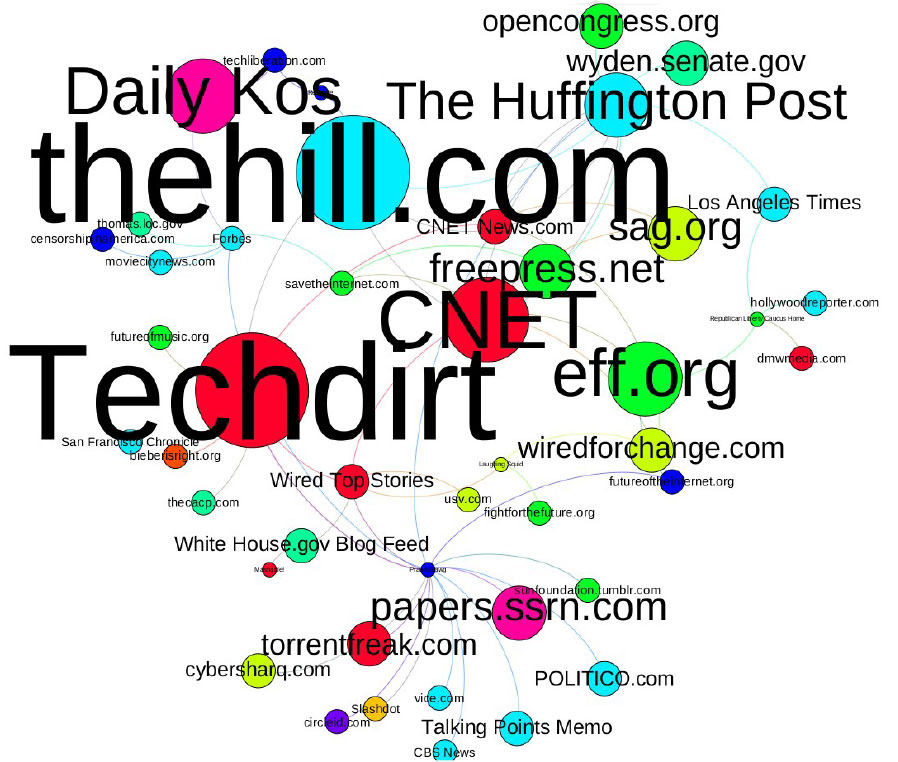

The following week, the first in November, is notable as the only weekly or monthly time slice we observe that looks remotely similar to the prevailing conception of the blogosphere or networked public sphere. It is the only week where Huffington Post, Politico, DailyKos, etc., and traditional media like the LA Times or the Hill, appear prominently. Similarly, Free Press and the Screen Actors’ Guild (SAG) make a significant appearance. On the other hand, this week also exhibits the possibility that in this network, academic work tackling the issues, rather than simply dueling press releases, can gain visibility. Here, the links to Derek Baumbauer’s paper in SSRN are prominent, driven at least in part by his own cross-posting and linking to them on several platforms like Prawfsblawg. The more “normal” look of this first week provides sharp relief for the remainder of the month, and in particular for the development and emergence of activism, in this case, American Censorship Day. Beginning in the second week in November and continuing from then on, that newly-created site, initiated by the co-founders of Fight for the Future, Participatory Politics Foundation, and Demand Progress with Public Knowledge, the EFF, and support from the Mozilla Foundation, became a major point for coalescence on action, and ultimately the model for the January 18, 2012 protests.

November 7-14, 2011

The prominent appearance of the New York Times during this period reflects, however, the continued importance of the major outlets. It reflects widespread linking to Rebecca McKinnon’s opinion piece explaining how SOPA and PIPA would strengthen China’s repressive firewall and import part of its capabilities to the United States.

In the map of the last week of November, several interesting features emerge. In addition to the obvious continuity, YouTube becomes a prominent platform, although no single video dominates this effect. The Business Software Alliance (BSA) receives much attention when it announces, on November 21, that it has reversed its position and now opposes SOPA. Research papers receive substantial attention; here, Allan Friedman’s analysis of the effects of SOPA on cybersecurity, published on brookings.edu, and survey results of research conducted by Joe Karaganis at the Social Sciences Research Council (SSRC) suggesting that the practices targeted by SOPA and PIPA are rare, and that public opinion supports a certain level of “copy culture.” Finally, the possibility of individual voices emerging periodically at critical moments is exhibited by the visibility here of Brad Burnham’s tumblr.

Week of November 21

A weakness of simple visual examination of the the maps, however, is revealed by the discrepancy between size and location of the node describing Alex Howard at O’Reilly Radar. His posts link to all of these highly-visible sites, and his node is located at the center of the link economy. However, because he acts by identifying and linking out to these nodes, rather than being linked-to, his bridging role does not “pop out” in a simple visual examination of the maps.

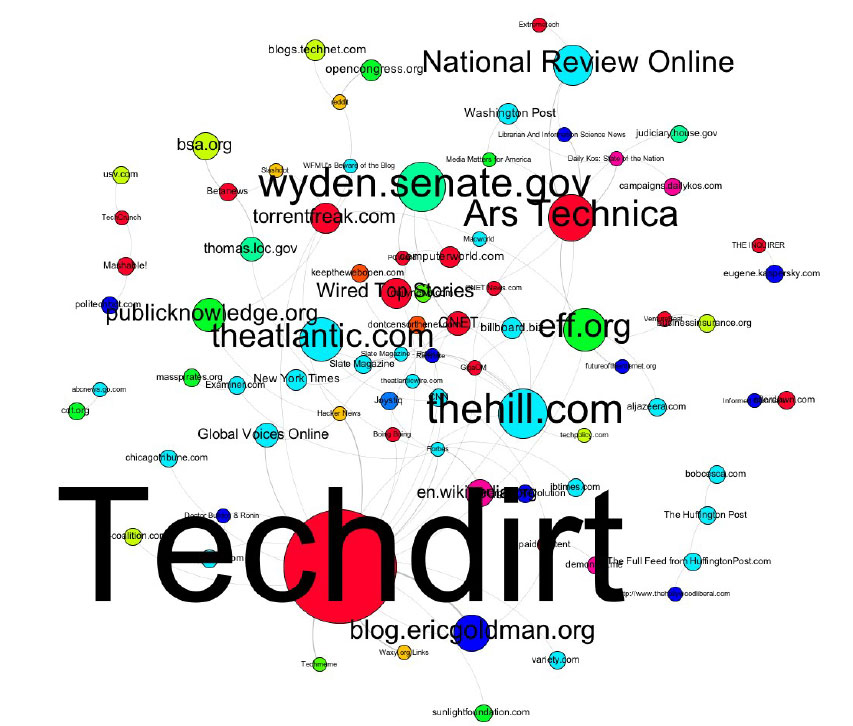

In the first two weeks of December of 2012 some of the action shifts back to D.C.; the National Review conducts dueling editorials as the right wing tries to reconcile between its members who support SOPA and those who oppose it. Sunlight Foundation’s review of contributions to members gets some linking, but the most interesting observation, from the perspective of the role of individuals and the mobilization of expertise, is the prominence of the analysis of the SOPA managers’ amendment developed by law professor Eric Goldman on his blog.

December 2012, Week 2.

December 2011, Weeks 4, 3

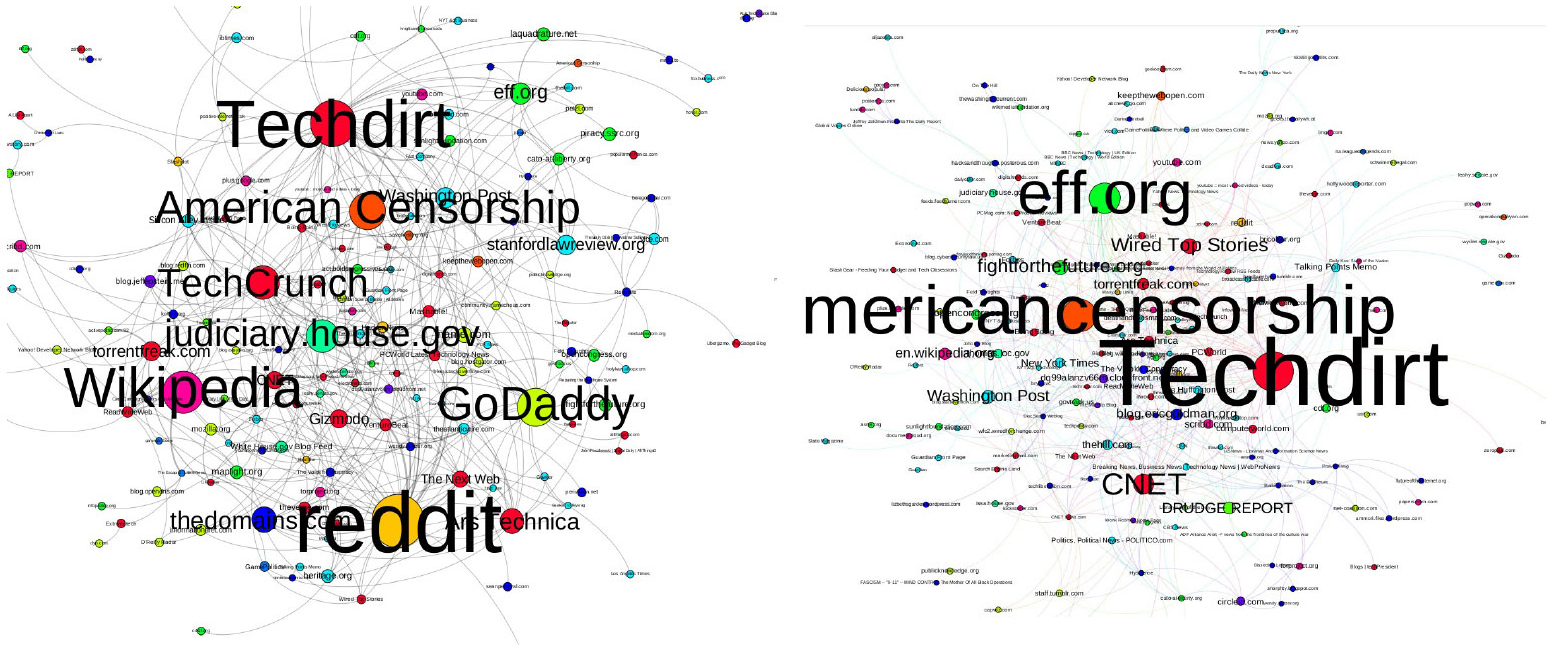

On December 21, 2011, the House Judiciary committee released a long list of corporate supporters of SOPA, in the hope of bolstering the claim that SOPA was good for business and innovation. The difference between the map before and after that event is stark, and provides one of the clearest examples we have of (a) the dynamism of the networked public sphere and (b) the possibility of converting discourse into action. It marks a major mobilization by online users, initiated by a single reddit user, to boycott Go Daddy for its support of SOPA/PIPA. Go Daddy retreated and abandoned the acts almost immediately. Following this boycott, we later see gamers follow a similar path in January, with users pressing customer support sites and sharing their queries and answers from vendors on sites like Kotaku, Joystic, mommysbestblog, and epicgames. The bottom half of the map during the fourth week of December is a stark instance of converting talk into action in the networked public sphere, as well as an instance of how a single speaker, with an idea, can move a large group.

Furthermore, while this map cannot distinguish between reasons for links to Wikipedia, an analysis of the actual links that make up the aggregate reemergence of Wikipedia as a major node in the fourth week of December shows a mix, with a significant portion linking to the debate launched by Jimmy Wales within Wikipedia as to whether SOPA is so dangerous to the open Internet that Wikipedia should shut down in protest for a day. The debate within the Wikipedia community, including over two thousand participants in the decision, was itself a fascinating instance of direct democracy—in this case, within the community of contributors to one of the world’s more visited and important Web sites.

The overwhelming story of January is the explosion of action and attention around the blackout on January 18, 2012. The single week of January 16–23 saw over three thousand five hundred stories on SOPA and PIPA, about 40% of the total number of stories between the introduction of SOPA and its defeat, and about one third of all stories throughout the 18-month period we studied. In this particular moment of massive mobilization, certain of the long-standing core nodes remain visible: Techdirt, CNET, and Ars Technica; Wikipedia; the EFF; and Open Congress and Fight for the Future. The new major node, which had already emerged during the prior week, Whitehouse. gov, is the administration’s public declaration of its opposition to SOPA/PIPA, a declaration made in direct response to a petition drive that garnered over fifty thousand signatures using the platform of petition.whitehouse.gov. The only other notable feature is the growing role that reddit came to play in the last three weeks of the campaign, following the initial activation around the GoDaddy boycott. By the week of the boycott itself, reddit is located at the very heart of the map.

The major flip in support in the House and Senate between January 18 and 19 clearly shows that the protest of January 18 closed the deal. But it is impossible to understand that day without also understanding the discourse, framing, and organizing dynamics of the preceding 17 months. This period, as we saw, was comprised of a highly dynamic, decentralized, experimentation-rich public sphere, where different actors played diverse roles in diagnosing the problems with the act, re-framing the public debate from “piracy that costs millions of jobs” to “Internet censorship,” and organizing for action. Clearly, our analysis does not cover all aspects of the organization. We have not studied Twitter; we have not studied back channels we know existed, such as mailing lists. There are individuals, like Marvin Ammori, whom we know from interviews and available published accounts played a major organizational and intellectual role, but do not show up in our data using public-facing communications alone. Despite these limitations, the data do cohere to a remarkable extent with our qualitative understanding of the dynamics.

January 2012 Weeks 1 and 2

January 2012 Week 3: detail

January 2012 Week 3 Overview

Perhaps the SOPA/PIPA events were unique. Perhaps the high engagement of young, net-savvy individuals is only available for the politics of technology; perhaps copyright alone is sufficiently orthogonal to traditional party lines to traverse the left-right divide; perhaps Go Daddy is too easy a target for low-cost boycotts; perhaps all this will be easy to copy in the next cyber-astroturf campaign.

Perhaps.

But perhaps SOPA/PIPA follows William Gibson’s “the future is already here, it’s just not very evenly distributed.” Perhaps, just as was the case with free software that preceded widespread adoption of peer production, the geeks are five years ahead of a curve that everyone else will follow. If so, then SOPA/PIPA provides us with a richly detailed window into a more decentralized democratic future, where citizens can come together to overcome some of the best-funded, best-connected lobbies in Washington D.C. Time will tell.