Chapter One

The African Charioteer

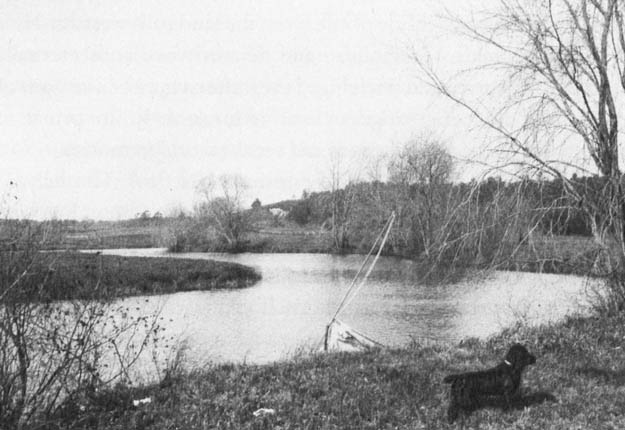

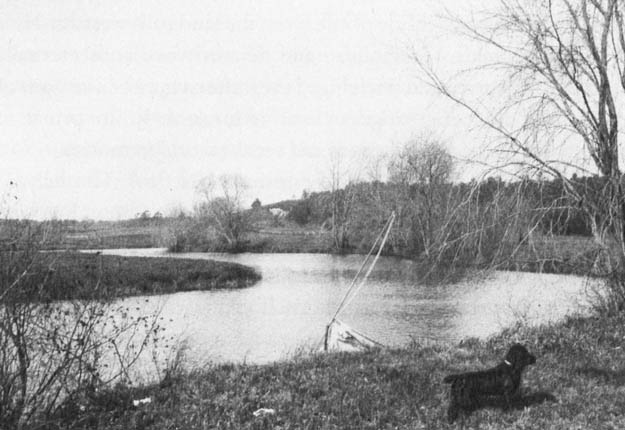

Concord River, 1911

“A photograph is only a fragment, and with the passage of time its moorings become unstuck. It drifts away into a soft abstract pastness, open to any kind of reading.”

—Susan Sontag

April 6, 1911, Concord, Massachusetts:

As far as the eye could see that day, nothing moved. In the foreground, a dog, a black spaniel, stands immobilized, nose pointed forever toward the horizon. Beyond the dog, a river, stilled to a rippled skein of marble, winds through the landscape. The halyard on the mast of a skiff pulled up on the riverbank hangs in a lifeless curve; streamside trees and shrubs are caught in mid sway, and on the other side of the river, the land rolls westward in a rising wave, fields, farmhouses, and distant woodlands eternally fixed in early spring and unchanged even after a hundred seasons of growth. It’s a sleeping kingdom waiting for some future prince to break through the thorn hedges and set the world in motion.

The shutter snaps. The river resumes its flow. The halyard begins to flutter. The inanimate dog breaks into a bounding run, and the photographer, a trim black man in a dark suit and a bowler hat, removes the plate holder and slips it into an oblong carrying case at his feet. He straightens himself and, with one hand resting on the oaken tripod, stares out at the landscape he has just trapped, his alchemy accomplished.

There are two other men in the field that day, both white. One has a neat, graying beard and is dressed in rumpled tweeds and high-topped calfskin boots, much worn from years of outings. The other wears a blue cotton overshirt and a heavyweight Winslow German vicuña cloth sport coat and woolen trousers. These two stand apart from the black man, squinting toward the scene that will reappear at some future point fixed on the glass plate the black man has just extracted from the camera. The white men have field glasses with them, and as they look out across the landscape they raise the glasses periodically to sight the ducks that wheel and settle over the river in small hammering flocks.

This is early spring in New England. It is a sunny, warming day, about eleven o’clock in the morning judging from the shadows cast by the standing dog. Somewhere up the hill, behind the little group of men, you can hear the sound of a piano emanating from the half-opened window of a farmhouse. Inside the house, in the parlor, a copper-haired woman dressed in a nobby shirtwaist of silk Duchess satin is leaning over the keyboard, tentatively sounding out the opening bars of Edward MacDowell’s “To a Wild Rose.” Somewhere, off beyond the low hill to the south, a horse whinnies; somewhere the sad three-note whistle of a song sparrow sounds off.

Across the river a flight of red-winged blackbirds rises up from the marshes and resettles, a small flock of ducks comes whistling down the flood, and the white men shift in place, raise their field glasses, and then agree to move on. Their intention today is to sail upstream to the wide waters of Fairhaven Bay to look for birds. The black man waits, then unscrews the camera, packs it into a square-shaped leather case, folds the tripod and hoists it over his shoulder, and the three of them walk toward the river. The dog is first, crisscrossing the path, snuffling everything, then the white men, then the dark man in the rear, carrying most of the equipment. You see them drop below the hill, legs first, then midriffs, then their shoulders, their hats. And then they are gone.

The woman at the keyboard sounds a full D-minor chord. A strand of auburn hair comes loose and falls over her smooth forehead. She has China blue eyes and hums softly to herself as she plays.

Alternatively, you might reverse the flow of time and begin on the morning before the photograph was made.

The 8:42 train from Boston, via Cambridge, Belmont, and Lincoln, heaves into view around a curve, slows, and with much squealing and steaming halts at Concord Station. A natty little man with a round, balding head and darting eyes jumps briskly onto the platform and looks around expectantly. This is Mr. Samuel Henshaw, executive director of Harvard University’s renowned Museum of Comparative Zoology and a man known for his orderliness and punctuality.

In spite of the fact that Concord is a mere fifteen miles beyond Cambridge, this amounts to a trip to the wilderness for Mr. Samuel Henshaw, and, always prepared, he carries with him on this occasion a heavy twisted hickory walking stick and wears his newly purchased two-buckle rolled lumberman boots in case of possible encounters with savage dogs or snakes, possibly both.

Henshaw is greeted at the station by a tall, imposing figure with a high forehead, a rudder-straight nose, serious dark eyes, and a well-trimmed beard. This would be William Brewster, the ornithologist, founder of the Nuttall Club, the American Ornithologists’ Union, president of the recently organized Massachusetts Audubon Society, and a well-known figure at the Harvard Museum.

The two men shake hands, Henshaw formally, the heels of his new boots snapped together, and the two of them walk to the front of the station, where Mr. Brewster’s new Model T Ford touring machine is awaiting them.

Lounging against the high doors of the vehicle, his legs crossed and arms folded, is a dapper black man, who straightens slowly when the two white men appear. This is Brewster’s manservant, known to the white community by his surname, “Gilbert”—better known among his peers in the Cambridge black community where he lives as Mr. Gilbert. Mr. Robert A. Gilbert, that is, the pianist.

This man, in his current guise as “Gilbert,” opens the driver’s-side door for the white men, who, after some deliberation as to who should enter first, settle themselves in the backseat. Gilbert leans into the automobile and sets the spark and throttle levers, then walks slowly around to the front of the car and slips his left forefinger through the choke loop. He waits for a second, then yanks the ring and at the same time throws the crank mightily with his right hand. The engine barks, sputters to life.

It should be noted that in the year 1911 this process is an art fraught with many pitfalls—failed or false starts, occasional broken arms from the kickback of the crank. But for Mr. Gilbert the act is carried out with an air of balletic grace, a slow dance in the palm courts of the Ritz.

Now in the driver’s seat, Mr. Gilbert releases the emergency hand brake, presses down the low-speed pedal with his left foot, and, as the machine begins to growl and roar, eases up the pedal and shifts into high gear. They move off from the station, riding high above the throng, passing through the rural streets of Concord town like European dignitaries, the only machine that will pass that morning. They are headed northward to Monument Street and Brewster’s country home, “October Farm.”

Henshaw would spend the day and the night there with Brewster and Gilbert, ranging the fields and water meadows of the Concord River in search of birds. He would pass the night at Brewster’s “camp” by the riverside (and shiver the night through—partly from cold, partly chilled by the ghostly hooting of the surrounding owls) and then return on the morning train the next day. We know all this because a few days after his return Henshaw wrote up an account of the visit, inscribed in vaguely mock heroic phrases, as if he were ascending some undiscovered tributary of the Amazon. Henshaw described Brewster’s automobile as a chariot, the village as an outpost, and the Concord open lands as wilderness tracts. He also described the driver of the automobile—Brewster’s “African Charioteer”—who conducted the two of them through the wild interior of the province of Concord and ultimately to the country hacienda of William Brewster.

Suffice to say that this Henshaw was not a well-traveled individual.

The so-called African charioteer was a small, well-formed man, aged 42 at the time. He wore a dark wool four-button jacket, a white starched shirt with a detachable collar, and a black tie. For this occasion, and perhaps for his own entertainment (Brewster would not have cared what he wore), he had donned a conductor’s cap with a freshly polished black leather visor and a hatband with two brass buttons. Inasmuch as they were traveling eastward, toward the sun, he wore the cap at a slight, almost unnoticeable angle, the shiny visor pulled down to shade his large dark eyes. Gilbert, it appears, was good at roleplaying. Like most men and women of his race living in the United States of America in 1911, he had to be.

Gilbert drove with a relaxed, although formal poise, both hands on the wheel, head fixed forward, his eyes glancing left and right, reviewing the familiar landscape of Concord as the vehicle rolled on. There was some banter between the white men in the backseat, and at one point Brewster leaned forward and jokingly admonished Gilbert to drive with care. Top speed of a 1910 Model T was all of twenty miles an hour. But these carriages were noisy and still new to the streets of Concord; the local horses were suspicious and tended to bolt.

The air was clean and fresh that sunny day, and as they swept eastward through the town, they passed small white houses set back from the street behind picket fences, freshly whitewashed for the coming season. They passed the old brick-front market, with the wooden bins of local vegetables set out on the sidewalk for the shoppers. They puttered by the livery, and the mill dam, and Wright’s Tavern, where, one hundred and thirty-six years earlier, local farmers and tradesmen had assembled to plot resistance to what they viewed as the repressive government on the other side of the Atlantic.

The two white men in the backseat chatted formally as they rode along, perhaps even uncomfortably. Henshaw was a bit of a problem at the museum, carefully attending to more details than were necessary, even down to the number of paper clips doled out to the hardworking secretaries. There had been talk among the staff members at the museum, even at the upper levels, and Brewster knew it. But Mr. William Brewster, as far as I can determine, was a man who kept his opinions to himself. His field notes describe what he saw, not what he thought, and his personal diary, which he maintained along with his field journals for over twenty-five years, are a circumspect accounting of birds seen, of dogs, of works in progress at his farm, or the arrivals and departures of his house-guests.

Did Gilbert eavesdrop as these two chatted in the backseat? Did he size up this Henshaw for his known flaws? Gilbert and Brewster were intimates in a manner that we now, in the early twenty-first century, would be hard-pressed to understand, an interdependency that fed the daily lives of each. They had spent nearly every day together for fifteen years, either in town at Brewster’s locally famous bird museum on Brattle Street in Cambridge, or in the field and camps on the river at Concord, or sometimes on expeditions into the wilds of Maine and northern New Hampshire. If anyone knew of the little tempests at the museum it would be Mr. Gilbert, even if Brewster had not shared a word with him. Gilbert was a good listener and reader of character, and he had a sharp eye for white behavior. But he too was circumspect, kept his own counsel, was ever polite, knew when to make his appearance and when to stay in the shadows, when to speak and when to remain ignorant. Or feign ignorance.

Even at home, among his own people, he was formal, an inscrutable presence. His inner emotions, it was said, were expressed at the keyboard, and even there he favored airs and arias, the theme from Ponchielli’s La Gioconda, Chopin mazurkas, the new piano works of Amy Beach and Edward MacDowell, and sentimental popular songs such as “The Roses of Picardy.” On Sundays he consented to Baptist and Episcopal hymns. And once or twice a year, at night, when he was in a certain mood and alone in the house with his wife, Anna, Mr. Gilbert descended to the lower depths and deigned to play a few of the currently popular low-class rags, his left hand arcing across the keys in the bouncing, offbeat stride style, and he, almost, but not quite, smiling.

Gilbert was not fond of jazz, even though he was an accomplished pianist, was not given to histrionics, or boasts, or, what seemed to him, the loud braying laughter one sometimes heard on the streets from his people. His employer, William Brewster, also despised the new form of music known as jazz, eschewed theater, rarely went to church, except at Christmas and even then only at the behest of his wife, Caroline. He avoided clubs, rarely drank, and ironically, given the fact that he now owned one, hated the new machines known as automobiles.

Gilbert quite agreed.

The souls of these two men, master and servant, one white and born with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth, one black and from humble beginnings, had, by some fluke of fate or history, been forged in the same smithy. Nevertheless, the vast divide of the American social and racial chasm yawned between them. As the African American scholar Cornel West wrote, race matters. And as F. Scott Fitzgerald pointed out, the rich are different.

Gilbert proceeded up Monument Street, passing en route the farms and vegetable plots of Concord. Three miles along, he turned right up a long unfinished drive and halted at the main house. Here, with Gilbert’s assistance, arrangements were made for the outing. Gilbert carried out the rucksacks, field gear, thermoses, and field glasses. He packed an older model 8 x 10 mahogany Perfection Viewing Camera and a plate holder in a leather carrying case, and thus burdened the three of them set out down the old cow path beyond the house, past a field of birches, over the hill to a meadow above the Concord River.

Below this spot, by the side of the river, Brewster maintained several outbuildings landscaped with native trees, flowers, and shrubs. Here, he would commonly pass his days and visit with his guests—of whom there were many in those years. The little group of friends would often eat at the site, and sometimes even sleep there rather than return to the confines of the big house on the hill.

The cabin by the river was the third of Brewster’s various abodes, the fourth if you count a houseboat he maintained on Lake Umbagog in northern Maine. The first was his mansion “The Elms” on Tory Row on Brattle Street, in Cambridge. The second was the large, well-appointed farmhouse on Monument Street, set back from the river.

Brewster was a man who, in some circles at least, might be described as a traitor to his class. Although he was moneyed and never had to work, he had no interest in Society matters, was uninterested in politics. And although he was the founder and first president of a number of bird organizations and had many friends and allies, he avoided social events and the frivolous men’s clubs of Boston. Furthermore, although he was of good stock, that is to say a descendant of the Brewsters of Plymouth, because of poor eyesight in his youth, he was educated at home by his mother and did not attend Groton or Harvard—something that was de rigueur for most Boston Brahmin males. He was most comfortable out in the field observing birds. Very comfortable, in fact. Obsessed.

As the three of them worked their way toward the river they stopped often to observe the birds of the season. Gilbert acted as spotter on these occasions as would some local guide in the wilds of the North Woods. He spoke quietly, even casually, to Brewster.

—I believe I hear a bobolink, Mr. Brewster—

And a second later, there would be said bobolink, rising up from the field, fluttering and sailing only to drop down again into the long grasses.

Gilbert had a sharp eye and a good ear for calls. At one point in an open area, near a copse of trees, the little troop stopped. A medium-sized bird with a brown back and a red breast rose up, chirping, and landed on a branch at the edge of the woods, flicking its wings and tail and continuing to cluck.

—What would that be?—Henshaw asked.

Did Gilbert look over at Brewster briefly before answering? Was there an exchange of glances?

—That was a robin—Gilbert said haltingly, adding, sotto voce—Sir.

There must have been a certain undertone to all this. Samuel Henshaw’s brother, Henry, was a popular and well-known bird man and a good friend of William Brewster and his company of ornithologists. Samuel, by contrast, was an innocent afield.

“We were guided through the dense forests of Concord,” he wrote in his account of the day, “by Brewster’s faithful colored friend and helper, the redoubtable Gilbert, a skilled field observer and factotum for the great man.”

Slung over his shoulder on a thick leather strap Gilbert carried the oakwood tripod and, in his right hand, the leather, boxlike case with the camera and plate holders. In the meadow above the river, the three of them stopped while Gilbert set up the tripod and screwed the camera onto the brass plate. He swung the lens toward the river and stopped, eyeing the scene on the ground glass:

Roll of meadow in the foreground.

The river beyond, banked by black willows and buttonbush.

He framed the scene, fixed the high sweep of pasturelands, walls and woods beyond.

Tree swallows flitted above the river, chattering flocks of blackbirds started up and settled on the opposite shore. Above them, the great sky rose in cerulean blue. Behind them, at the house, the woman with the copper-colored hair struck an opening chord.

Gilbert sank beneath the black camera hood, twisted the knobs of the rack and pinion focusing devices, and then, as he focused, the dog bounded into the scene. Gilbert raised his head, whistled, brought him to a halt, and squeezed the shutter bulb.

The river freezes. Swallows halt in midair. The willows cease to sway. The spaniel turns to black marble.

Mr. Robert Alexander Gilbert, pianist and photographer, servant, valet, factotum, and gentleman’s gentleman for the estimable William Brewster, has stopped forever a small, isolated piece of the world as it stood at eleven o’clock in the morning of April 6th, 1911, in the village of Concord, Massachusetts.

For all we know he left something of himself upon the scene in the process.

Inasmuch as we know anything about the undiscovered country of the past, we know about the events of that day as a result of the invention in the 1830s of an ingenious device that had the capacity to concentrate light waves and permanently fix images on a chemically coated glass or tin plate. The camera is in fact an alchemist’s mortar and pestle or a shaman’s drum. It can alter realities. It can reorder the accepted flow of hours and days and arrest any given moment in the flight of time. The photographer, in the role of alchemist or shaman, has the ability to stop the world and hold everything in place, unmoving—the land, streets, people, skies, clouds, running rivers and streams, wind in the trees, flowing grasses, all stilled in midcourse, lovers caught forever in that ecstatic music, forever young. Whatever happened before the image was exposed and what happens afterward is open to interpretation. This means, among other things, that we, the invaders from a time yet to come, observing one of these captured segments, can make of it what we will. The photograph is not really an image incised by light on celluloid film or a glass plate. It is an imaginary history.

And so we can say with as much authority as any other extant record of that day that the three men spent the rest of the afternoon on the river, spotting birds, and that, toward dusk, they rowed and sailed back down the river to the bend at Ball’s Hill, where the cabin was located, and that here, roughing it (in the view of Henshaw), they had a dinner of eggs and canned SS Pierce meats, with mustard and white bread, prepared by Mr. Gilbert, who, it should be noted, this being the relatively broad-minded environment of Concord, sat at the table with the white men.

The following morning Gilbert drove Henshaw back to the 9:22 train at Concord station and then returned to the farm.

A few days later Henshaw received a short note in the mail.

My Dear Mr. Henshaw,

I found five dollars under a pitcher in your room this morning. Fearing you may have left it by mistake I am writing to ask what disposition you wish made with it.

Respectfully yours,

R. A. Gilbert

The handwriting is small, scrolling left to right. Also neat. The passive voice regarding money, the distancing, the formality, are intentional.