Chapter Eleven

A Journey Through the Memory House

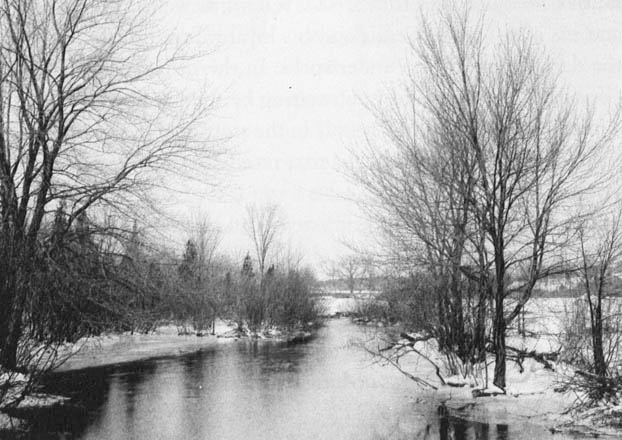

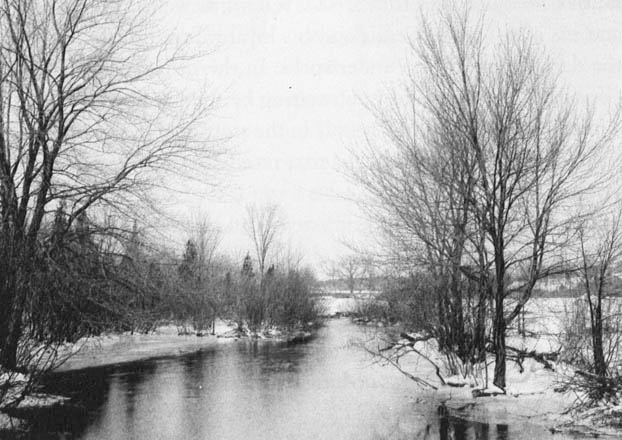

Concord River, undated

“The camera is a mirror with memory.”

—Anon

It was late winter in New England, 1920, and a warming trend had melted the ice of the Concord River so that the dark stream filled and flooded over the riverbanks. Below a seamless sky, the river flowed northward between the bankside red maples, leafless now, their branches and trunks black with rain. It was nature morte, as the French term a still life painting, only worse: no flowers or fruits, no dead game birds and rabbits, no color. No birds, and the trees skeletal, the sky a uniform pearl and paled to white, sunsets and sunrises mere slashes of dull light, the outline of a structure with no color.

He may have taken the train out with Caroline and ERS that winter day, then left them to putter in the house above the river while he went out for a walk. He trod over the hill, through Mr. Brewster’s beloved birch field, where the two of them so often spotted the bluebirds, then down through the cow pastures where, in spring, the meadowlarks boasted their presence with their two-note whistles, and then onward, dropping always downhill, through the dark pines, where the two of them once photographed the nest of young great horned owls, all whited out in their immature plumage. Farther along still, to the place where they once saw a fox making off with a grouse in its mouth, and finally to the old cabins where the two of them had spent so many days. The doors were secured, the lack of human footprints in the snow indicated to him that no one had been here for months; he had to break through the crust and force his way to the doors—a small black figure in a vast white woods, all bundled in scarves and his fedora pulled down low, his tricot box coat, the collar drawn up high and tight on his neck.

He carried with him this day his Maximar roll-film camera with its Zeiss Tessar f:4.5 lens and double-extension bellows—easily portable and folded now in its leather case. Gilbert tended to work in the pictorialist style, soft focus, warm, favoring patterns, the broken reflections of tree limbs in meltwater, gray tones shading from black to a filtered blurry white of new-fallen snow, the light softened and even kind in an otherwise heartlessly cold season. I wonder if, alone by the river, away from Caroline and ERS, far removed from the scurrying of his attentive daughters, who without a mother grew up quickly and watched after him; I wonder if, alone there by the river, a lump did not rise in his throat and a short sob escape.

He snapped open the camera, raised it and squinted through the viewfinder, adjusted the bellows with the focusing lever, and then turned away, a tear blurring the landscape.

I only wonder, but the images are sad and long. Cold. The quiet beauty of the frozen world. Time and death, and the river flowing.

A scream overhead, and he looked up to see a rough-legged hawk circle once and stream off to the southeast.

Mr. Brewster would want to know about that. It was not common in 1920 to see the rough-legged hawk in winter, so many having been shot out of the sky by vindictive farmers and sportsmen practicing their aim. It was in these same years that gunners would collect at high points along the migratory flyways, and, for no particularly good reason, slaughter thousands of hawks and eagles as they passed along the ridges, riding the thermals southward on their migratory routes. By this year, the Lacey Act, which made it a federal crime to shoot anything but game birds, had passed, Mr. Brewster and his Audubon Society having been instrumental in its passage. But nevertheless the practice continued, causing a precipitous decline in the populations of predatory birds.

Kind-eyed William Brewster was now dead and buried, and the river ran on without him. At his many memorials and subsequent encomiums, Brewster had been recognized as the very dean of American ornithology, the father of field studies of bird behavior, the founder of two professional organizations dealing with ornithology, writer and conservationist, and also a gentleman. Brewster’s childhood friend, the American sculptor Daniel Chester French, who later would design the Lincoln Memorial, had made a short expedition to Concord earlier that year. He and Gilbert had scoured the fields around October Farm in search of a suitable memorial to the naturalist. Gilbert thought he remembered that somewhere on one of the sharp ridges above the river he had seen a particularly beautiful granite boulder, so he and French had tramped the ridge looking for it. It was not in the place that Gilbert recalled, so they walked on farther southward, and then found it, a large pink granite stone, about three feet high, leaning out of the autumn leaves. They dug it out, and French eyed it, studying the shapes, the grain, the subtle colors.

—Perfect—he said—but I won’t touch it—

—Don’t—Gilbert said—he would have liked it the way it lies—

—You have a man to haul this?—French asked.

He did. Patrick and company, the Irish and Swedish workers who had helped around the farm. Gilbert said he would arrange to have the boulder hauled up to the farm where it could be loaded on a motor truck and carried to Mount Auburn Cemetery.

French came to the cemetery the day it was put in place, once again eyeing the placement, requesting to have the boulder moved a foot this way, twisted upward a half a foot that way, and then changing his mind and shifting it again, and then turning it to set the flat face forward. They had the wording of the inscription ready, a passage from The Song of Solomon:

“For lo, the winter is past, the flowers appear on the earth; the time of the singing of birds is come.”

Caroline had turned over the funeral arrangements to William’s lifelong friend R. H. Dana, who set the date for July 14th and retained the Concord minister Dexter Smith, who was an avid birdman and a friend of Brewster’s, to conduct the service. There was a big crowd at the funeral, and all the dignitaries, the Harvard men, the members of the American Ornithologists’ Union, members of the Nuttall Club, Miss Minna Hall, one of the two founders of the Audubon Society, along with her cousin and cofounder, Harriet Hemenway, and the company of associated friends and relatives and all of them dressed in black.

The Reverend Mr. Smith spoke in darkly religious terms of the great man (knowing full well that William Brewster was not a religious man) and it was all ashes to ashes and dust to dust and all to the earth return, and they stood there in their black hats and veils, and one or two tears slipped from the squinty Brahmin eyes, from the women mostly, and even Mr. Gilbert remained dry-eyed, holding his emotions in for the time being, here in the presence of all the powerful whites, and he the only black man there that day. Men did not weep openly in 1919—except for Patrick. They could all hear him back there sobbing and blubbering and blowing his nose loudly with a great waterfall of tears rolling down his ruddy old cheeks. Sanfred’s father, Lars Bensen, who stood near Patrick in Nordic fortitude, must have been uncomfortable. But the black-clad rows of Brahmins standing in front would have understood—“He’s an Irishman; they’re so emotional, so childlike, can’t help themselves”—whereas in fact a great number of them would have loved to wail that day, such was the depth of their feeling.

Gilbert may have choked back a tear himself; but it was more in lament for the exigencies of life; this was a dark and clouded summer for him. He had cried freely at Anna’s funeral a month earlier, burying his face in his big white handkerchief, his shoulders hunched and shuddering and his daughters weeping beside him, and the old preacher strutting and jabbing the air and singing loud that here was a daughter of God lying in her casket, gone now to meet Jesus in that bright and shining Kingdom where now there was no separation, no differentiation by color, or by creed, or by class, no distinction—white or black, or even Irish, and wasn’t sister Anna entering now into that lustrous Heaven.

And inasmuch as this was a musical family, the full choir was there that day, all fixed in clean black silken robes with white vestments over the gowns, and the girls choir, hair straightened, all lined up and accompanied that afternoon by two violinists and a man with clarinet, Mr. Baldwin, whom the Gilberts knew from Robert’s Washington Street days, and the preacher sang out then—swing low now, sweet chariot, swing low and carry your sister upward—and the tears by this time were rolling freely down Mr. Gilbert’s cheeks and he just can’t help himself, sobbing bitterly, and his daughters—especially little Edyth, the youngest—wailing, although Mary, the female head of the family now at age 18, was handling herself well, it was said. And then the organ and violins pitched in and the clarinet whined sadly, hitting here and there a flatted third and seventh, and all the choir starts: Sway right. Sway left, dipping with each oscillation, and then a step forward, “Swing Low,” step backward, “sweet chariot,” and they begin to clap, a slow workaday hammer, singing and swaying and even though he doesn’t do that normally, there he is, rocking along with the rest of them—hard to the east and hard to the west, rolling and dipping and singing out in that great, darkened baritone of his, “A band of angels coming … for to carry me home.”

It was even worse for him at the gravesite, when they lowered Anna into that brown earth on Montbretia Path in the Cambridge Cemetery by the river Charles, where their only son, Robbie, lay buried. It was July. Hot. The winds were off the river, the sun flattening the light and making everything a yellow white and ugly. The black community of Inman Square was there that day, all gathered together for yet another funeral (there had been many in the past year because of the 1918 pandemic, the plague of the Spanish Lady); all the church people were there, as well as Mr. and Mrs. Allen, their neighbors, and Anna’s cousins, and a few people from across the river in Boston.

When Gilbert and his daughters got home to Inman Street after the funeral there was a big bouquet of flowers waiting, and a little card, signed by the Brewsters (arranged by Caroline and ERS, not by William) “with deepest regrets.”

He and his daughters and Anna’s cousins drank iced lemonade in the parlor, and later, after everyone had left, Mr. Gilbert sat down at his upright Estey piano and he and Mary and Emma and Edyth sang a few of the old hymns that Anna had loved.

“It’s what they did in that household,” Gilbert’s old neighbor, Tom Allen, told me. “They sang together, you could hear them even on a weekday night, they sang together.”

But after the girls went up to bed Mr. Gilbert stopped singing, he could still hear them sobbing through the floors and, hearing this, he broke down again and then he got down on his knees all by himself and folded his hands together and alone there on the first floor of the big house, he prayed.

Also in attendance at William Brewster’s funeral were a few members of the staff of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, where Mr. Brewster had served as curator of birds, among them the director, Samuel Henshaw, who, it should be noted, was probably there because he felt that in his position it was important to be seen in the company of the august figures of the world of natural history. Samuel was the brother of William Brewster’s very good friend Henry Henshaw, an avid birdman who shared correspondence with Brewster and who recently had published a book about his bird adventures. Frank Chapman, who was by then with the American Museum of Natural History, in New York, was also there. Although younger, he too was a good friend of Brewster’s, and, along with Daniel Chester French and a younger man from the Harvard museum named Thomas Barbour, would write one of the biographical introductions for Brewster’s four posthumously published books.

This Thomas Barbour was a rising star at the museum. He was a Harvard graduate, but was not, as were so many of the Brewster crowd, a native Bostonian, and was not an ornithologist, but concentrated primarily on reptiles and amphibians. He was a large, heavyset man with a mass of curly hair, and had great jowly cheeks, and a profound curiosity about the living things of the world. He and his wife Rosamond, who was a star in the Brahmin constellation and well off (as was Barbour’s family), ranged the world every year hunting new specimens for the museum’s growing collection.

Everybody liked Thomas Barbour. He was a shambling hail-fellow-well-met type who would slap you on the back and invite you out for a drink, and if you professed even a passing interest would invite you to come hunt obscure lizards with him on remote islands of the South China Sea. On more than one occasion he had been known to leap over café tables in exotic places and go crashing after the fleeting shadow of some rare lizard he thought he had seen. His wife was no slouch either. She was a bluestocking low-heeler, as the Boston Brahmin females were categorized, and hardly knew the difference between a reptile and an amphibian before she married Barbour, but she went everywhere with her world-rambling husband, and on a few occasions even personally helped capture strange snakes for his collections.

Barbour had met Robert Gilbert through Brewster and came to know him better after Brewster’s death, instructed by undocumented orders from Brewster that arranged to have Gilbert come over and carry on the work he was doing at the Brattle Street bird museum at the Harvard museum, funded, I believe, by the legacy of William Brewster.

Brewster had left most of his estate to Caroline: all the furniture, most of the books in his extensive library, silverware, his watch, his automobile, plus fifty thousand dollars, and the house and land at 145 Brattle Street, along with additional properties to the north and east. His collection of mounted birds and bird skins, nests, and eggs, along with their cases and cabinets, his manuscript catalogues, and his collecting pistols, he gave to the Museum of Comparative Zoology. To his loyal assistant, Robert A. Gilbert, he willed a thousand dollars.

The will also instructed that on the death of Caroline the sum of $60,000 should be conveyed to the museum, three quarters of which should go to the payment or part payment of the salary of a competent ornithologist, who would take charge of the collection, the remaining one quarter to be used at the discretion of the director. It was funds out of this one quarter, I think, plus perhaps a little from the larger fund, that financed Gilbert’s position at the museum, a post that he held, off and on, for the rest of his life.

Barbour was not technically the curator of the museum at the time of Brewster’s death. Officially Samuel Henshaw was still curator, but for some years the staff and board had been plotting how to get rid of him. He was a very good accountant; his books, his desk, his management of the collections and materiel were precise. But he was rigid, humorless, unimaginative, and antisocial, and not liked by any of the people who were associated with the museum He reigned from his window desk in a large upstairs room at the museum, surrounded by his terror-struck female staff who, following his minute instructions and attentive oversight, did virtually all the work as precisely dictated by Henshaw. There is an undated photograph of him, caught unawares, staring out the window with his round Lenin-like bald head, shadowed by natural light. He kept on his person all the keys to the museum cabinets and doors and closets; you had to request permission from him to open a cabinet, and he required that his secretaries request paper clips from him rather than help themselves. He was an entomologist by training and had been hired in 1892 to oversee the management of the place and did such a good job at his menial tasks that he thoroughly impressed the equally controversial Alexander Agassiz, who had no interest in petty details. Henshaw had insisted, with constant wheedling, to have his title advanced from “assistant in charge” to “curator.” This was essentially the same title held earlier by the world-famous naturalists Alexander and his father, Louis Agassiz, and it gave Henshaw, in effect, control of the whole museum, including the management of the generally independent-minded staff. Alexander Agassiz, who was arguably as skilled a naturalist as his father, and a world authority on coral reefs as well as embryology, tired of the details of the management and resigned in 1898, which catapulted Henshaw ever upward in the hierarchy.

Barbour had first visited the museum when he was 15 years old, and loved the place at first sight. He was such a sharp naturalist even at his young age that he recognized an error in the labeling on one of the exhibits and privately vowed that he would someday return to Harvard and become director of the museum. He was a New Yorker, from a rich family, and normally would have been bound for Princeton, but he came to Harvard instead to be near the collections and the renowned biologists associated with the research the museum was then carrying out. He somehow managed to have himself posted to Cuba during the First World War, the equivalent of the brier patch for him, given the number of as yet unidentified lizards and snakes on the island. He had rich friends; he was a crack biologist; he himself contributed funding to the museum through his family; he got along with people; and he had that insatiable curiosity and energy that often drive the likes of great naturalists such as Brewster and company. Furthermore, unlike anyone else at the museum, he got along with Samuel Henshaw, an art in itself.

When Barbour came back to the museum after the war, he was 25 years old, Henshaw was then 67. Everyone, from the president of Harvard College, A. Lawrence Lowell, on down to the secretaries, and probably Mr. Gilbert himself (although he wouldn’t have mentioned it, even if asked), felt that the Henshaw regime had lasted long enough and that Barbour should assume the role of director. In fact he already was, de facto. Henshaw would never answer people’s letters, would not respond to requests, and cloistered himself away from personal encounters so that staff members had to go through Barbour to negotiate their requests. Finally, in exasperation, Lowell came to Barbour to help him convince the little tyrant to retire. Barbour, incredibly, was sympathetic to Henshaw. He was a precise little old man, he said, who had no life other than the museum—in all of his thirty odd years there he had never taken a day of vacation. Barbour convinced Lowell to let him ride, and Henshaw held on for another ten years, supported by his ebullient, outgoing subaltern. When, in 1927, he was finally ordered to retire—he was by then 75 years old—he flew into one of his rages, turned on Barbour, his sole protector, spit his cobra venom, and walked out the door and (to no one’s regret) never returned. He took with him stacks of documents from the museum and made a cold fire of them in his home. Reportedly the fire burned for two nights straight.

Gilbert came into the museum in the midst of all this and was taken under the vast protective wing—the bulk, actually—of Thomas Barbour, who was his junior by twenty-five years. There is a certain cosmic justice in the fact of Mr. Gilbert’s employment there in these years. He was the first black person to work at the museum and the environment there was not particularly favorable to blacks, or for that matter anyone who was not Caucasian, or in fact, male. Harvard scientists, along with the staff of most other American institutions, had been deeply engrossed in the classification of races, an obsession that lasted well into the 1940s. There were still some American textbooks in the mid-twentieth century that placed Africans between Caucasians and gorillas on the evolutionary scale. In fact Gilbert’s presence at the museum, not to mention his popularity there among students and staff, would have turned the gorge of the founder, Louis Agassiz.

Agassiz was one of those all-round naturalists favored by natural history museums of the time. He had come to Harvard to deliver the Lowell lectures in 1846 from his native Switzerland, where he had made a name in the scientific community for his studies in both geology and ichthyology, his primary field. He is considered, even today, the founder of the field of glacial geology, and he was one of the most respected, innovative scientists working in Europe at the time. He stayed on at Harvard after the lectures, established himself in the department of science, and in time founded the Museum of Comparative Zoology. When he died, in 1873, his son Alexander took over as curator.

Louis Agassiz did his most insightful work abroad while he was still young, but as he aged, he seemed to have become stuck in his opinions. He was notorious for his rejection of Darwin’s theories on evolution, and he stubbornly maintained his position even after the scientific community came to embrace the theories. Furthermore, for all his good science, Agassiz was an abject racist who was repulsed by Negroes.

Stephen Jay Gould, another controversial Harvard professor who worked at the museum in the late twentieth century and who was a strident critic of the inherent racism of the early anti-evolutionists as well as contemporary creationists, unearthed and published in his 1981 book The Mismeasure of Man a damning passage from Agassiz, describing an early encounter with a perfectly innocent, probably gentlemanly, black waiter in Philadelphia:

… it is impossible for me to repress the feeling that they are not of the same blood as us. In seeing their blackfaces with their thick lips and grimacing teeth, the wool on their head, their bent knees, their elongated hands, I could not take my eyes off their face [sic] in order to tell them to stay far away. And when they advanced that hideous hand towards my plate in order to serve me, I wished I were able to depart in order to eat a piece of bread elsewhere, rather than dine with such service. What unhappiness for the white race to have tied their existence so closely with that of Negroes in certain countries! God preserve us from such a contact.

This would be standard fare were it to appear in some Ku Klux Klan screed, but the fact that it was written by a man considered to be the father of American science is worrisome.

Agassiz carried his racism through his life, but although not on record that I know of, Alexander, who was widely traveled, was probably a little more tolerant. Henshaw was at least polite and tried to be fair, but he probably did not accept blacks as social equals. Barbour himself may have carried all the contemporary prejudices too, but he was far more worldly than any of the previous curators, having spent weeks in the field with people of various colors, hunting his lizards.

I stepped into this somewhat cloistered world of the Museum of Comparative Zoology early on in my hunt for Gilbert. Shortly after my photographic land use project was completed, I took a job as research assistant for a man named Wayne Hanley, who worked at the Massachusetts Audubon Society and was writing a book to be called Natural History in America. My job was to scout out the artwork that would appear in his forthcoming book, and this begat many trips to the library of the MCZ, as the museum was called. It was during this time when I came to know Ruth Hill and an assistant named Ann Blum, who, among other useful contributions, discovered a Brewster photo album of a trip he had taken without Gilbert through the American South, down to Key West and on to Cuba. We were looking through this album one afternoon when I noticed a photograph of an ivory-billed woodpecker, a species that is now believed to be extinct. We also found the extensive diaries and journals of William Brewster with their meticulous accountings of bird arrivals, train schedules, and the daily comings and goings of Mr. Brewster and his associates.

It was in this collection that I also found one of the most reprinted photographs of William Brewster, a portrait by Gilbert of Brewster standing in front of one of the lodges somewhere in Maine, with his Belgian Back Action collecting gun crooked in his elbow and his rudder-straight nose poking out from a slouch hat with its brim folded back. He’s in tweeds that day, and high boots, staring off at the forest beyond, and has a brace of ducks dangling from his left hand.

While I was working in the library looking for artwork to illustrate Hanley’s book, it was my custom to take periodic breaks and go wandering through the inner sanctum of the back halls of the display rooms, where the offices of the biologists who worked at the museum were located. I was interested to note there, in the shadowed warren of narrow hallways, the tiny offices of some of the most famous names in American science: Stephen Jay Gould, E. O. Wilson, Ernst Mayr, and the ornithologist Richard Paynter. I asked Ruth Hill about the older biologists to see if I could find anyone who might remember Gilbert, but even though the museum tends to maintain its hold on employees, there weren’t many left. Ernst Mayr had come to the museum in 1953, after Gilbert’s death. Paynter, who arrived in the 1940s, had heard a lot about Gilbert, but never knew him. There was at the time an old entomologist, age 90, who still came to the museum every day to study his insect collections, but he had no memory of Mr. Gilbert—possibly not much accurate memory of anything, save insect genera.

During this time, through the auspices of a fellow researcher, I came to know a few of the scientists who used to inhabit the caves of the museum and was invited to join them at their regular midday meals in the Department of Malacology. These lunches were the remnants of midday meals established at the museum in the 1930s by Thomas Barbour and were held in what came to be known as the “Eateria,” a wide, airy room set at the end of the museum and lined with Barbour’s collected volumes on natural history.

In Barbour’s time, these repasts were elaborate, prolonged Roman feasts, consisting of delicacies such as elephant’s-foot stew, the meat of exotic snails, the sweetmeats of bush babies, and white grubs. Barbour himself was a prodigious eater and gourmand who would commonly down a quart of rum a day, and he presided over these meals with Rabelaisian gusto. The lunches began modestly enough with the installation of an electric stove and sink and refrigerator in the museum, but having discovered the culinary talents of Mr. Gilbert, Barbour soon expanded the festivities. Gilbert began preparing more and more inventive dishes, using first the meats from some of Barbour’s local hunting expeditions—ducks, geese, medallions of venison, terrapin soup, and the like. News of the quality of the presentation began to spread and soon visitors from outside the department began to attend, and as the popularity of these lunches increased, Rosamond brought a parchment guest book to the Eateria and attendees began signing in with the dates. President Lowell was a regular there and would often bring important visiting dignitaries from around the globe to the lunches—world-renowned biologists from Western Europe, Japan, and China. In time the guest book accumulated the signatures of visitors from more than forty countries. At the same time, the exoticism of the dishes began to increase as foreign biologists imported delicacies from their own countries and as the wide-ranging Harvard botany staff began bringing home tropical fruits such as mangoes, white sapotes, agles, and canistels and other exotic fare as yet unknown in New England, or even North America. Each of these new ingredients represented a challenge to the resourceful Gilbert, who, using his own devices and recipes, managed to present savory new dishes.

One of his lunches was even written up in Life magazine in the 1940s. Photographs show Barbour at table—a vast Roman emperor with full cheeks and a mass of marble-gray curls, holding forth, no doubt, on the virtues of rum and Chinese frog stew with diced pig’s ears and white grubs.

Gilbert, of course, was always there in the background, the invisible man as usual, but also as usual, the driver of the machine. He was versatile, able to switch menus or expand the quantities when it was announced to him that there would be ten more guests than expected that day. The few mentions of him in museum publications are couched in the race-tinged language of the period, “the loyal colored servant” with his “old fashioned courtly manners” and such like. He shadowed through the gatherings in his starched collars and his black suits, the silent presence, a mere adjunct as far as the collected dignitaries were concerned. As Gilbert himself used to tell people, with subtle self-mockery—he had been willed to the museum with Brewster’s collection of birds skins.

No one took especial notice while he was there. But they noticed when he wasn’t. After he died, the Eateria declined and eventually devolved to the old lunch hour of sandwiches and milk brought in from home.

The time I spent there was a period of upheaval in biological sciences. Up until the middle of the twentieth century, biologists based their work on field studies and were generally well-rounded, versed in botany, or mammalogy, as well as geology and herpetology and other fields unrelated to their own particular subject. But in the latter part of the century, as a result of the decoding of DNA and the subsequent advances in molecular biology, computers, new biometric tools, and quantitative methods began overtaking the adventurous world of field studies that had dominated the development of natural science in the past. It was no longer necessary to send bearded and bedraggled ornithologists and herpetologists out into the unexplored tributaries of the upper Amazon to collect original specimens to build museum collections; computers and molecular biologists could reveal yet undiscovered connections among life-forms by studying genetic codes in the sterile comfort of university laboratories—at less expense besides.

The old guard among the field staff of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, such as the ant specialist E. O. Wilson and the even more famous evolutionary scientist Ernst Mayr, who started the whole reexamination via genetics, were saddened by this decline. The lunchtime crew I was familiar with spent at least part of every meal peppering their dishes with laments for the decline of these expeditions to exotic, unexplored territories and the rise of a race of biochemical monks who now labored in laboratories filled with electronic devices. This decline was often contrasted with animated accounts of the grand museum expeditions of the past and the larger-than-life naturalists who were contemporaries of William Brewster. These included ichthyologists who scoured remote South Sea beaches and deep seas in search of unidentified species, malacologists who specialized in the parasites of extinct shellfish, famous bird collectors who were lost in the Amazonian tributaries, presumably eaten by cannibals, as well as authorities on the sex life of tamarin monkeys and on the deep-forest canopy flora of the Ituri forest in West Africa, and even students of psychoactive plants who, under the guidance of jaguar shamans and shape-shifters, had consumed all manner of bizarre mind-altering drugs. The consummate master of this latter group was Richard Schultes, a balding old man in steel-rimmed glasses whom I sometimes saw puttering around the museum’s famous glass flowers collection. It was said that by the time he quit his field studies he had partaken of most of the known psychedelic drugs of Amazonia.

But the ultimate hero of the contemporary Eateria was the wandering naturalist Thomas Barbour.

In the autumn of 1906, Barbour married Rosamond Putnam, who was a child of one of the old Brahmin families and a woman more accustomed to the social subtleties of thé dansants than the fetid forests of Borneo. And yet, the day after their wedding Barbour announced to Rosamond that by way of honeymoon they would embark on an expedition to the Dutch East Indies, a journey that had surprised but not deterred the fair Rosamond. This singular expedition began a lifelong voyaging. On this first trip, Barbour was charged and nearly slashed to death by a wild boar in the Sundarbans, and brave Rosamond had risked her life prodding a cobra for an action photograph taken by her husband near Lucknow. Later on, in China, while he and Rosamond were ascending the Si-kiang River, a local warlord had offered to have two recently captured pirates released from their cages and brought down to the steamer to be beheaded for the entertainment of the visiting foreigners. Rosamond politely refused that particular offer.

On all of these voyages, through the West Indies, through South America, Africa, and the then no less exotic swamps of Florida, Barbour collected his frogs and salamanders and snakes and lizards. He was indefatigable, and Rosamond seems always to have been in on the action. Barbour took many photographs on these various voyages, mostly of his newly captured specimens, but included among the albums in the museum collections were a few photographs of his wife. You see her there, ever straight up, dressed in her ankle-length crepon cloth skirts and white cotton shirtwaist with her flat, wide-brimmed straw hat fixed firmly over her brow. She stands there on the island of Amboina, squinting in the sun, thigh to thigh with bare-breasted women and half-naked warriors with penis sheaths and huge curving boar tusks fitted through their noses—and she, a banker’s daughter from Clarendon Street, more familiar with the delicacies of Lapsang souchong tea in Limoges cups than stews of still-paddling, fresh-caught frogs and roasted white grubs served with the meat of unidentifiable venomous snakes. At Japen Island, in the Dutch East Indies, one of their guides, Ah Woo, refused to go ashore inasmuch as too many Chinamen had been eaten there. At Wiak Island, as they approached the shore in their pulling boat, Ah Woo noticed that all the females of the tribe fled to their perched quarters and turned to stare back at them. Bad sign, he said, unfriendly males here, preparing for attack. No sooner had he spoken than a band of shouting, mop-headed natives, their nose tusks gleaming in the midday sun, appeared on the beach and began threatening them with spears.

One of the presiding judges of these last days of Barbour’s Eateria was a man named Richard Johnson who worked at the museum as an associate researcher in the malacology department. He was a 1951 graduate of the university who, not unlike Barbour, had started working for the department as a volunteer when he was 16 years old in the 1930s. He was subsequently drafted and sent overseas during the Second World War and then returned after the war to enter the college as a freshman. He was said to be a gentleman scholar of the old school who had produced more than fifty papers on malacology, most of which were published in scholarly journals of limited circulation devoted entirely to obscure species of bivalves, chitons, and snails and of no interest whatsoever to the general public. In the relatively cloistered world of shells, Johnson was a well-known character who smoked good cigars, had enjoyed a number of marriages, and even at age 70 liked to range through the New England countryside on his motorcycle. I was told by some of the other museum staff members that he was probably the only man left at the museum who might remember Mr. Gilbert. So I went to see him.

Johnson’s office was located behind a steel door in the upstairs gallery in the hall of mammals, just off the right fin of a vast skeleton of a sperm whale, which is suspended below the ceiling and floats above the lower galleries wherein lie the mounted displays of okapis, guanacos, klipspringers, and, in a large glass corner case of its own, a huge mountain gorilla with its fangs bared, beating its chest. All of these beasts were tended to and even stuffed for display by the versatile Mr. Gilbert in his latter years at the museum.

Having gained entry into the halls of the cosseted mollusk department, and having negotiated a narrow labyrinth of halls, I came finally to a door marked “R. Johnson.” There was a little ditty posted on the door that advised me that “if Johnson respondeth not, perhaps he is on a journey, or peradventure he sleepeth …”

I took a chance on awakening the sleeping scholar and knocked. There was a scraping of chairs from inside the office and a rangy man with a shock of gray hair and horn-rimmed glasses, perched low on his nose, opened the door—very much awake.

Following my usual introductory method, I described my mission while Johnson eyed me cautiously, as if I were slightly mad. He was at first nonplussed by my quest and stood twisting a pen in his long fingers.

“A black man who was assistant to Barbour?” he asked. “Here, in this museum?”

“Yes,” I said, “he is cited in papers and in his obituaries as assistant to the curator from the ’30s up to 1941. That would be Barbour, no?”

“Yes, but a black man? A Negro curator in the 1930s? I doubt it. This is a natural history museum, you understand. Maybe he worked at the Peabody.”

He was referring to the anthropology museum that is housed in the same building.

“No, it was here,” I said. “He worked first for William Brewster, then came here after Brewster died. He must have been here off and on, because he appears to have also been in Europe after the war.”

“Which war?”

“First.”

“This man is old,” he said. “I will confess to being long of tooth myself, but I’m not that old.”

I explained that Gilbert had returned to the museum in the thirties.

He thought some more, rambling through the names of various workers he had known and then he nodded vaguely.

“Come to think of it,” he said, “I do remember a black man here. But it’s not the same person, I don’t think. This man was a shuffling old Negro, like a porter on a train. He used to cook for Barbour and the distinguished guests of the Eateria, I think he was the one who was famous for his elephant’s-foot stew, which was a favorite of the regulars there. I think he also cleaned the exhibits and built shelves, that sort of thing, but he wasn’t a biologist, he wasn’t trained, just an old loyal servant. He was a shadow figure here. You’d see him in the halls …”

So be it. But there were one or two things the white staff of the museum did not know about the quiet old serving man who cooked their exotic stews, puttered around the exhibits of mounted bongos, tree possums, and civet cats who still live on today, forever frozen in their cases, their dusty glass eyes fixed on some feral past.