CHAPTER 3

LACAN’S THEORY OF THE

AS THE IMPOSSIBLE TO SAY

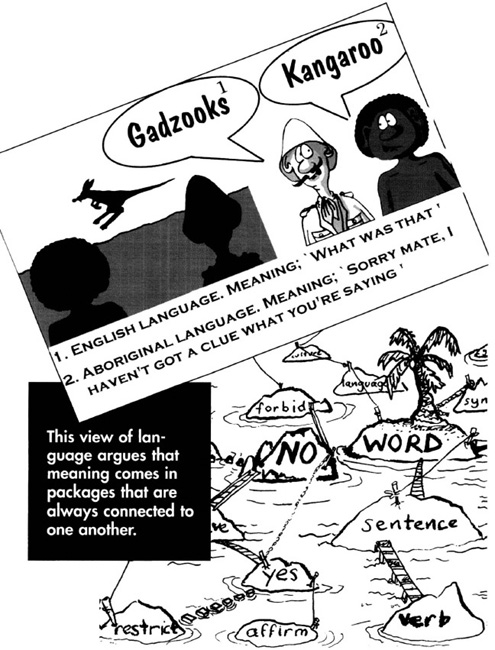

By the 1960s Lacan had a broad theory of the psyche or mind, with three different categories: ‘the imaginary, the symbolic and the real’. He pictured the three tied tightly together like a knot. The imaginary (in chapter one) is the domain of images, the symbolic (in chapter two) is about language or signifiers: what is the ‘real?’

The ‘real’ is not an account of reality, or the ‘objective world’ but a kind of recurring impossibility, a ‘return of the repressed’. When you read ‘real’ in this book it is meant in Lacan’s sense, not in the ordinary sense. The real for Lacan is ‘the impossible to say’, or ‘the impossible to imagine’. To understand this idea we should look first at a morsel of the history of science:

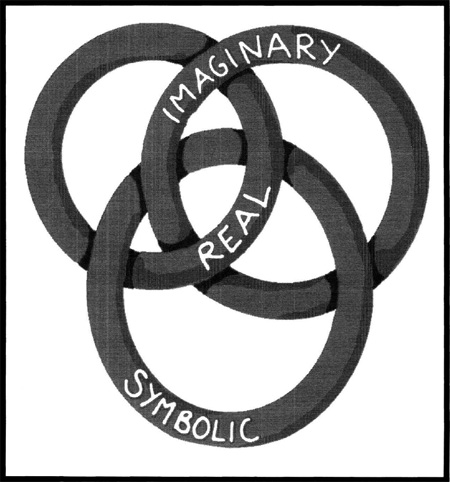

In 1687, the world was being shaken up in a big way by Isaac Newton. People were so impressed by Newton’s brilliant theories which, for the first time, accurately predicted the movements of the planets, and all manner of mechanical things, that almost everyone thought that it would only be a matter of time until science could predict all phenomena, the whole universe and everything in it. Man would know everything, and medical science would cure all ills.

It is now widely believed that there are at least three fatal problems with this idea:

The first is the problem of how we measure ourselves, measuring ourselves, measuring ourselves, measuring our... This is another version of the homunculus problem.

The first is the problem of how we measure ourselves, measuring ourselves, measuring ourselves, measuring our... This is another version of the homunculus problem.

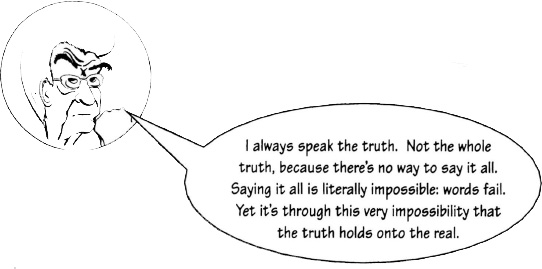

Or as Lacan said:

Here is the third reason why we cannot have knowledge of everything:

Here is the third reason why we cannot have knowledge of everything:

In 1925 another physicist, Werner Heisenberg, had some shattering news. Heisenberg had discovered that it was necessarily impossible to measure some things. He had been trying to measure the position and the speed of an electron as it orbited the nucleus of an atom, whizzing around, like the earth orbiting the sun:

Heisenberg could either find out what the velocity of the electron was, or he could find out what the position of the electron was, but he learnt that he could not find out both. Knowledge of both was mutually exclusive. His discovery produced a new attitude to science, with expectations completely different from those of Newton’s time. Science could no longer be relied on to solve all the problems of life. Since Heisenberg, science, however useful and informative, has become yet another set of impossibilities.

Heisenberg said that the very act of measuring the electron’s speed had an effect on it, and so produced the impossibility of knowing the electron’s position. So, instead of magically eradicating our impossibilities and our ignorance, science has become a detailed specification of them.

The real is that which cannot be symbolised or imagined at a particular time. So for Heisenberg, the real would either be the speed of an electron, or its position, whichever of the two was excluded. Lacan argued that we all endure important impossibilities in our lives. We all face big questions and dilemmas that cannot be avoided, and whichever option we choose, we necessarily exclude others. For instance, being a man, or being a woman entails specific impossibilities for each of us, as does being homosexual, heterosexual, black, white, a parent or childless.

One impossibility we all suffer from is the ideal of perfect communication. We all have to continually endure being misunderstood, misheard and misquoted. We are condemned to use language and to always be misunderstood, whatever precautions we take, even by people who do their best to understand us.

Word meaning is something that seems to be in flux. Word meaning shifts about beyond our control. If you want to know exactly, and without any doubt, what a word means you might try looking up the word in a dictionary. What do you find?

More words, and each of those words has a meaning you can read, but only as more words, and each of these words has a meaning offered by more words... This sea of signifiers with its potentially infinite connections is the same one in which we are each, as subjects, represented.

Lacan argued that our individual lives centre around what is real for each of us, that is what is impossible to say, and that our individual symptoms—which we all have—are the symbolic expression of what is real for us.

The real is about impossibilities, the impossibilities of language and life. Let’s look at the real by returning to the idea of word meanings in flux, with an extreme example, one that we all have some experience of:

A trauma is an important impossibility and refers to an experience in a person’s life that he has not been able to sufficiently symbolise, or to put into language. Trauma is an experience in the category of the real.

In the talking cure, in psychoanalysis, there is a putting into words, a symbolising of difficulties and traumas. This has the effect of metamorphosing the trauma, of changing the meanings that a particular signifier has for a subject. So ‘the trauma’ is actually changed by being spoken about. It becomes more clearly symbolised and less real.

Just as measuring the position of an electron means that you have an effect on the electron’s speed, so it is possible with psychoanalysis to change what is in the category of the real for a subject, through speech, by getting the patient to talk.

But it is not possible though to remove everything real from the trauma so that it becomes an empty category, containing nothing. We all have to live with the real, with ‘the impossible to say’. If we manage to find the words to say something that we could not say before, we can only do so at the cost of introducing new items in the real which we then cannot talk about. Language always introduces new indeterminacies, uncertainties and the renewed division of the subject. This is why Lacan argues that language is a universal trauma or wound, taking a unique form for every subject.

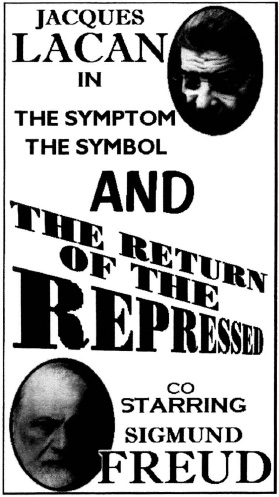

Lacan says that the real always returns. ‘It’ comes back, again and again and while each time ‘it’—the object of repetition—may be different in some ways, the pattern is the same. Freud had noticed that when somebody had a particularly difficult experience, a ‘trauma’—something that they had been unable to speak properly about— that some aspect of their experience would always return.

What form does this return take? It takes the form of the symptom, which is the return of the repressed. The trauma always returns in a symbolic form, as language, but is distorted by the ego and repressed, so that it is not consciously recognized. In this way the traumatised subject is ‘protected’ from coping consciously with their difficulty. Unless you can remember what you had repressed, it will return, again and again to haunt you, in symbolic form.

While ‘the return of the repressed’ sounds like the title of a ghostly horror film, it describes the patterns we find ourselves repeating. You might find that your love affairs always last until your partner proposes marriage, or that whenever you speak to your grandmother, you don’t know why, but you become depressed. Perhaps you always lose your keys on every birthday or anniversary?

The trauma returns in a disguise, as, for instance, the phobia of the woman who feared public spaces, because she didn’t want to be seen as a fallen woman, acting on her desire and living with its conflicts. Traumas also return in dreams and slips of the tongue.

You will have to wait until the chapter on psychosis and ‘Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem’ for the second reason why we cannot ‘know everything’.

You will have to wait until the chapter on psychosis and ‘Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem’ for the second reason why we cannot ‘know everything’.