CHAPTER 4

JOUISSANCE

AND ITS RELATION TO THE REAL, THE SYMPTOM, FANTASY AND DESIRE

In this chapter we will look at a kind of sexual satisfaction that Lacan called ‘jouissance’ and distinguish it from pleasure. Some other terms are introduced: ‘need’, ‘demand’, ‘desire’, ‘symbolic father’, ‘fantasy’ and ‘transference’.

How can you tell if what you are considering is a symptom or not? In medicine the diagnosis of symptoms is largely a visual matter: the patient is inspected by the trained eye of the doctor.

The doctor sees the outward images or signs and then infers the identity of the underlying disease.

Medicine

In psychoanalysis diagnosing symptoms is very different. So much so that perhaps the word ‘symptom’ shouldn’t be used for both. First of all, the psychoanalyst doesn’t look, he listens.

Psychoanalysis

Freud was the first to listen carefully to patients, to study their language rather than their images, and to investigate the unique meanings that key words had for each of his patients. He did not make the assumption that he always knew beforehand what his patients’ words meant.

This is demonstrated by two patients with exactly the same outward ‘symptom’, ‘anorexia’, but each has completely different underlying problems. One anorexic’s symptom was her way of trying to communicate her experience of sexual abuse by her father, while the other anorexic saw her mother die painfully of breast cancer and was terrified of becoming a woman with breasts and suffering her mother’s fate. So, because of the diversity of human life and language, there never could be a diagnostic dictionary of fixed meanings for psychoanalysis as there is for medicine, where meanings are far more fixed.

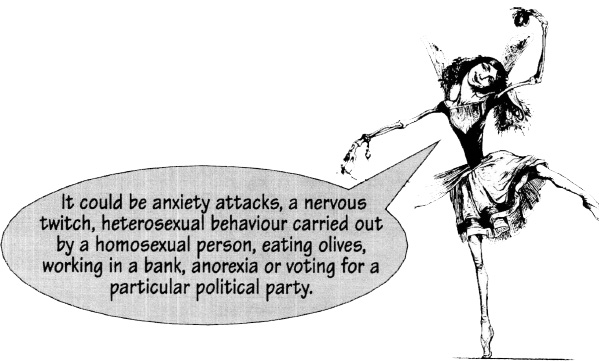

Psychoanalysis is difficult for clients and analysts, not only because there is no diagnostic dictionary to rely on, but also because it is not always obvious what a patient’s symptoms are. A symptom might be any behaviour or experience.

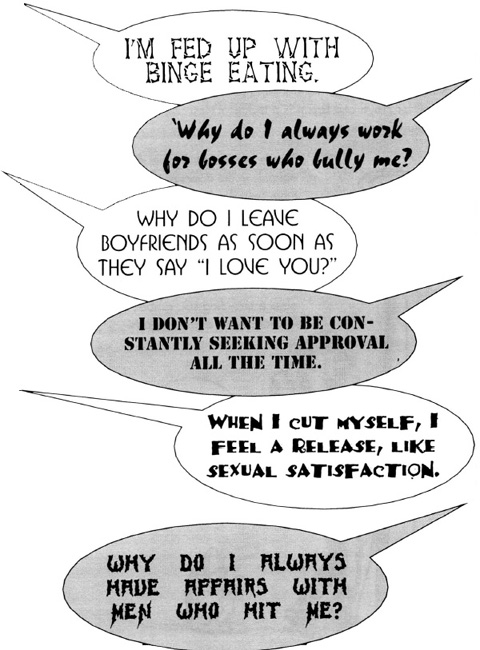

The symptom is often something that patients complain about, but it can also be something about which they are unaware. But typically patients complain about their symptoms. They might do this by saying:

What do analysts listen for in their patient’s language when looking for symptoms? A special kind of sexual satisfaction, excitement or enjoyment that Lacan called ‘jouissance’. ‘Jouissance’ is French for ‘coming’ as in orgasm. Lacan used this word because he thought that people take a sexual enjoyment in their symptoms, usually secretly. Jouissance is often an unconscious enjoyment. Lacan argued, along with Freud, that people often take sexual satisfaction or jouissance in all sorts of activities that appear to have nothing to do with sexual intercourse. ‘Sexual’ for Freud and Lacan is a technical term and means far more than sexual intercourse.

People are extraordinarily different from animals in the diversity of things that give them sexual enjoyment or jouissance. People and animals can get sexual satisfaction or enjoyment from smells, images, sensations, but only people can get sexual enjoyment from words, from language, and an extraordinarily diverse range of objects including silk, rubber, black leather jackets and lampposts.

Animals are relatively straightforward about sex, it has a fixed meaning for them. But some people get sexual enjoyment or jouissance from masturbating with a shoe, some with telephone calls, and some from whipping or being whipped. But it is almost universal for words or signifiers to have an erotic effect, especially when they represent the desire of the other. The most erotic thing for most people are signifiers, hearing another speak their desire.

Let’s get back to the idea of jouissance as sexual enjoyment, and its connection with suffering. If you ask someone to tell you about their experience of orgasms, usually they will tell you what a wonderful thing an orgasm is. But, imagine an experiment: if you were to stop someone having their orgasm just five seconds before they had it, what do you think they would experience?

But people don’t talk about the discomfort and pain, they only talk about the fun bit that comes afterwards, the jouissance. Now compare this situation with an hysteric (we will find out more about hysterics in chapter seven). Typically the hysteric complains:

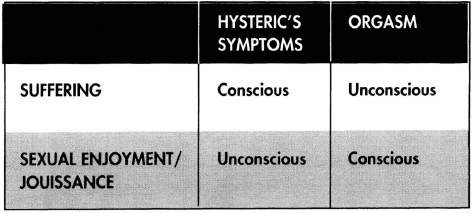

But hysterics won’t usually tell you about the satisfaction that they take in complaining. No doubt such hysterics actually suffer pain, but they also enjoy their symptoms. Their enjoyment is usually unconscious: whereas the subject having an orgasm also suffers pain and discomfort, but it is usually unconscious, while s/he enjoys the orgasm consciously. So orgasms are a kind of hysterical symptom with a change of emphasis!

The pleasure in sex starts by gradually building, with a linear increase or acceleration of pleasure. Freud called this the ‘Pleasure Principle’. When the increase has been well established, the ‘plateau phase’ begins, when the pain and discomfort start setting in. This pain, which is the interruption of the linear increase of pleasure, becomes increasingly unbearable, until, finally, when the pain is at its height, there is a sudden release of jouissance, of sexual satisfaction.

So the variations of meaning in language, and suffering have all become intertwined with jouissance, with sexual enjoyment. This knotting together of different elements make up the symptom.

When someone asks to be psychoanalysed it is usually because they have become aware of some difficulties or problems that they have, and cannot tolerate their suffering. Typically patients say that ‘I want my symptoms to disappear’. But it turns out that whatever their symptom is, the symptom is not the patient’s fundamental difficulty, but their solution!

The symptom is a clever trick, a compromise that ‘speaks the truth’ about the patient’s trauma and desire, and what is real for them. But it does not speak with a voice that is clear or easy to understand. The symptom encodes, in symbols, what is in the real. In the course of a psychoanalysis, typically taking some years, the meanings of the symbols or signifiers are worked through, and the often complicated meanings of symptoms can become clearer.

In contrast, a psychoanalytic approach would try to understand how drinking solved a problem for him, and more specifically, how drinking might be connected with his suffering. Perhaps then he might be able to change, assuming that he was ready to pay the price of change. It is also possible that when he discovers his reasons for being a drunk, he may prefer to remain a drunk. We will look at this ethical problem of a cure in more detail in chapter eleven which asks:

‘What is the Good of Psychoanalysis?’

What the symptom always does is to produce an excitement or jouissance. Jouissance is an attempt at compensation, when the patient tries to ‘balance out’ his suffering.

But as with all symptoms, despite the client’s complaints, there always seems to be some jouissance. This enjoyment or jouissance is not the same as pleasure.

JOUISSANCE ≠ PLEASURE

Pleasure and pain are within Lacan’s category of need. The satisfaction or enjoyment of jouissance does not address needs, such as the need for warmth or food. Jouissance is always a compensation, an attempt to patch up shortfalls in the categories of ‘demand’ and ‘desire’ as a way of living with the real.

THE SYMBOLIC FATHER

The symbolic father is not the same as the biological father, whose sperm helped create the subject. Nor is the symbolic father necessarily a man who lived with the subject and played football with him, or her. So what is the symbolic father?

The symbolic father is any agency that separated the young subject from its mother. So for example, if the mother leaves her child to go to work, then mother’s work is the symbolic father. If a lesbian lover spends time with the mother, separating the mother from the child, then the lover is the symbolic father. The symbolic father can even be the person who does the mothering, if she is identified as pushing the child away. The separation is regarded by the child as the mother’s desire for someone else, for someone other than the child.

How does Lacan’s theory of the symbolic father help explain the relation of need, demand and desire? First let’s look at three technical terms that Freud and Lacan introduced to psychoanalysis: ‘need, demand and desire’—they ore often confused.

NEED

‘Need’ is something physiological such as the need for food or for warmth. Not much about people is simple, but if you could imagine a need on its own—which would never happen—it would be something that could be completely satisfied. If someone is cold, he can be warmed, and if he is hungry, he can be fed. Need in this sense can be eliminated, temporarily.

A newly born infant is mostly in a state of need. He has sensations of pain and pleasure which are more or less managed by whoever mothers him. Let’s call that person the ‘motherer’, it could be an older brother, sister or the father. So the motherer is the sensation manager of the infant. S/he feeds and changes him, keeping him neither too hot nor too cold, and appearing to the infant to be very much in control of his pain and pleasure. The motherer is powerful in relation to the baby’s helplessness. Note that this relation of power over sensations, of another person’s mastery over your pain and pleasure is one definition of sexuality, of love or the erotic.

As the infant gets older the motherer feeds him less often, but talks to him more. What is she doing? She is feeding her baby words, signifiers. In the meantime the infant quickly gets the idea, from his lack of power, and the motherer’s power, that he had better find out what the motherer wants, so that he can give it to her, so that he can continue avoiding pain and getting pleasure. At this point the problem of the real, of impossibility, takes centre stage for the infant.

In order that the infant can be reassured that he is giving his motherer what she wants, as she makes herself increasingly absent, and increases the time between his feeds, he starts learning language, swallowing the signifiers that she has been feeding him. Infants are pressured to speak by their pain and pleasure, by the absence and presence of their powerful motherer. In this way the baby identifies the management of his suffering with his motherer, with the mother tongue.

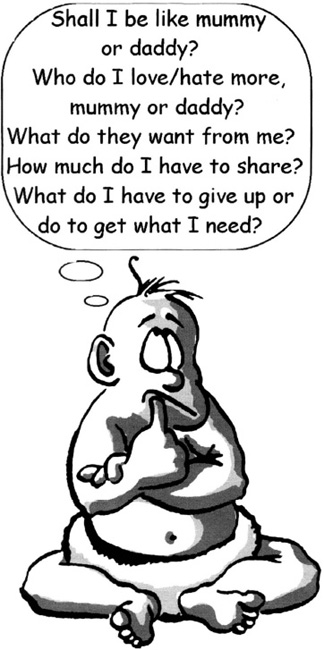

Once the child has learnt to speak he has a whole new set of problems that are far more complicated and difficult than the simple needs he started out with. In addition to managing the old problems, his needs, the pain and pleasure, he has new problems: demands, loves and hates, as well as difficulties with ideals, values and ethics. He has problems of conflict with ‘the good and the bad’, and identifications to make and break. And, crucially, he has to come to terms with the symbolic father, with the other who the motherer desires.

What happens after the first phase of need? There is a kind of progression, from need to demand and then on to desire.

DEMAND

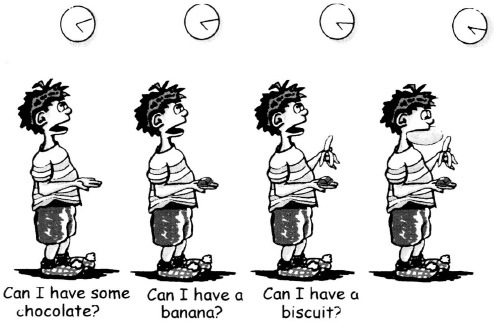

‘Demand’ is a more difficult idea to explain than need. Here is an example of a demanding little boy who says to his mummy:

Whatever the boy is physically given, he will ask for something else. What the boy is looking for above all is not an actual object, a biscuit or banana, but an object that does not exist. He is looking for something he will not be given. So he will continue testing his motherer’s resources and patience until he finally succeeds in finding something that she will not give. The object of demand cannot exist! For some spoilt children being refused the object of your demand is something that only happens when you have grown up. Until it does you will keep on demanding, and demanding, and...

Note that while the object of need—a sensation—can be supplied completely, the object of demand cannot be supplied at all, because it doesn’t exist! Need and demand in this sense are opposites.

There is a popular aspect of demand: love. Demand is always the demand for love. What is love? Loving is being in a state of demand, of wanting to give something that you, the lover cannot give, and wanting to receive something that your loved one cannot give you.

DESIRE

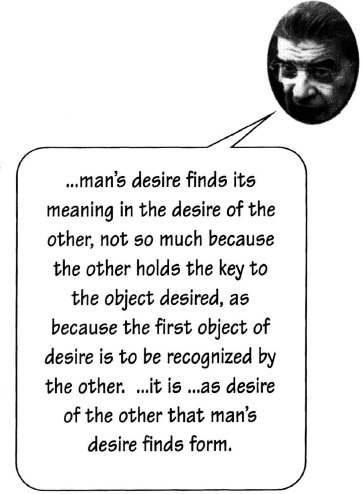

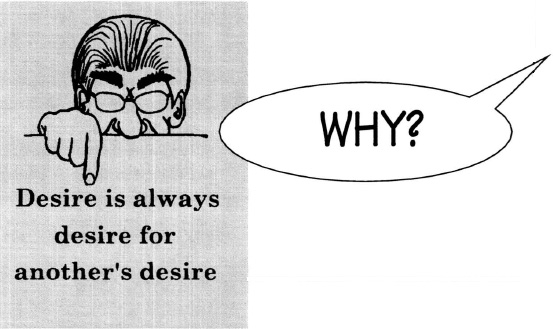

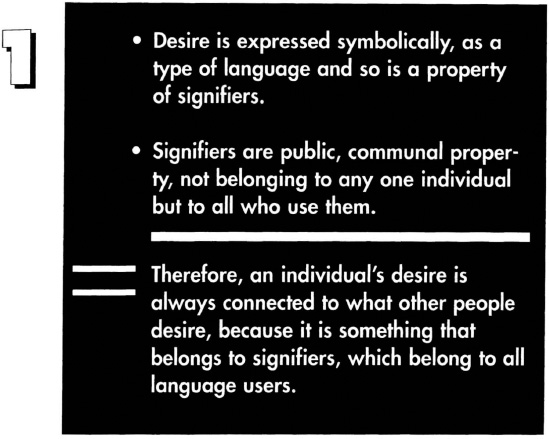

Desire is another difficult idea, and, Lacan argued, uniquely human, because it is a property of language. Language is communal property, being owned by no one individual, so each individual desire is part of language. An individual’s sexual desire, for instance can often be aroused by a particular form of words, typically those of a potential lover signifying their desire.

Desire dominates our lives and sets us apart from all other animals. Desire is another word for ‘lack’, for something that is missing: the object of desire. Desire can change its object, and desire often hides—although it will be revealed in dreams, slips of the tongue and symptoms—but it always organises the subject’s life in a far more comprehensive way than we ordinarily believe, as we saw in the case of The Fallen Woman.

ere is a review of the terms introduced in this chapter and their relation to each other:

ere is a review of the terms introduced in this chapter and their relation to each other:

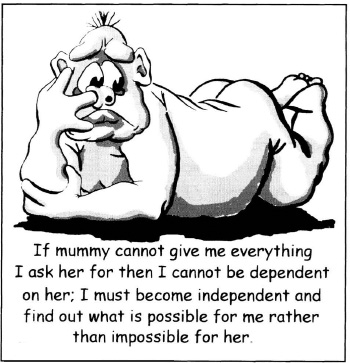

There is a progression, from need to demand and then on to desire. During the first phase of need, the dependency of the child on the motherer is established. In the following phase of demand the child is working in the opposite direction, to separate from the motherer, to separate his desire from his motherer’s by placing impossible demands on her that s/he cannot meet. When s/he cannot meet the child’s impossible demands, the child’s dependence on her has been proved false, and his or her independence of the child’s desire has been proved to exist. This proof usually entails the motherer being presented with thousands of fatiguing examples and repetitions of demand. The child reasons:

Once this proof—that the motherer cannot provide all that the child demands-is sufficiently clear, the child is able to begin to start identifying its own desire; its own desire as separate from its mother’s. This is why children are so demanding; their frustrated demand is what gives birth to their desire. Parents identify their own desire out of their frustrated demand with their parents, so desire is the rejection of demand. This is why every generation of parents say:

So desire emerges from the child’s own frustration, from his demand, addressed to his parents, to which he found an inadequate response. Of course each child usually manages to find his own impossible demands. This is why it is naïve to try to give a child everything she asks for. If a child doesn’t work through the impossibility of its own demand it will never discover its own desire, and it will demand until it dies. To extinguish demand the child must go beyond it and suffer frustration.

To summarise:

A ‘need’ is for sensations, that can be ‘given’.

‘Demand’ is for an object that cannot be given.

‘Desire’ is for an object that can sometimes be reached.

But, if the object of desire is reached, then it no longer remains the object of desire; another object will become substituted in its place.

In the shifting from need, to demand and on to desire, there is always some residue. All adults obviously continue to have basic needs, although these do not usually seem as urgent to us as they are to young infants. We have to have some needs in order to survive; we need some food and warmth. And demand is also something most of us have at least a minimum of. A minimum of demand is necessary to keep desire going, and for us to love.

But if you have too much demand, as most of us do, then some of your demand could be metamorphosed to desire. If you have not proved—with your impossible demands—what others cannot do for you, then you will not be able to discover what your own desire is. To find out what you really want in life, to discover your desire, you must have experienced your demands being unmet, some impossibility, an experience in the real. This is one reason why life is hard.

When someone has worked through his demand he can speak his desire. Such a person could tell you what they desire and how it drives their life. But many people live in a sort of trance, half asleep, with hardly any idea what they really want. They do not know their own desire and they do not follow it.

But they know best, or at least better than anyone else, what their best course of action should be. Each one of us is The Authority regarding our own resources. If, for example, you live in a homophobic society it may be far easier for you not to recognise your homosexual desire, than to risk rejection by your employer, friends and family. It might be best for you to hide your desire from yourself and others, rather than suffering the consequences of coming out.

For such people who do not act on their desire—most of us—jouissance is the compensation we provide for ourselves, through the symptom. The symptom makes jouissance, and is a tortured compromise between the demand for love, and the desire to speak the truth of unconscious desire plainly, so that everyone will understand.

A subject’s demand for love can never be properly articulated because demand, or love, is for an object that does not actually exist. This is why love has always been such a popular theme of songs, poetry and art throughout history.

THE WORKINGS OF DESIRE

In this section we will look at the ways in which pleasure, desire and jouissance are not fixed but in flux—because of their relation to language—and how the fantasy works to keep desire going by using a fixed idea.

The infant according to Freud is ‘polymorphously perverse’ He meant by this that the ways in which the infant can derive pleasure and satisfaction or jouissance are not fixed, but can vary enormously. There are infinitely many forms that can provide pleasure and satisfaction, but as the child ages, the sources of his pleasure and satisfaction become increasingly fixed. All pleasure for the infant is in relation to the motherer and the symbolic father, so pleasure takes on a relation to language, to signifiers.

Adults too have an extraordinary range of sources of sexual satisfaction including words, breasts, specific smells, hair, genitals, rubber, animals, a particular voice, a kind of look... But as time passes the source of jouissance, or the object of desire becomes increasingly fixed.

The list of objects of desire for infants is infinite, because sexuality is not fixed for people as it is for animals. Remember that if you wave any red object at a stickleback, at the right time of the year, he will do a mating dance. That is what ‘red’ means to a stickleback. It has one and only one fixed meaning. Because people have language, and because we con mote all year round, meaning is in flux, especially sexual meaning.

The meaning of sex is not fixed by the seasons or reproduction. In fact, it is often very difficult to separate meaning and sexuality when people are concerned, but not so with the other animals.

The world is a very chaotic place for infants, where meaning is not fixed. In the whole animal kingdom human infants are the most disorganised and most helpless, for the longest period. If you compare a baby with a dog, an ant or an elephant at six months, or at any time up to five years, it is the human who is the most helpless, the most dependent.

To express yourself in language you must have learnt the rules of grammar and word meaning. So repression and expression are two sides of the same coin. In order for there to be an expression, there must have been repression. So, for example, it is now common in Europe and America for Jews to assimilate, to become absorbed into the culture of the country that they live in. To do in Rome as the Romans do. Typically such Jews do not practise their religion, and they often marry non-Jews. But if there was to be a strong resurgence of anti-Jewish racism, with Jews being murdered and treated badly, you could be sure that there would be a renewal of Jewish culture, and a failure to assimilate. Many ‘Jewish atheists’ would find God, and there would be a return to the old traditions.

Sometimes there is too much repression which is called ‘trauma’, sometimes there is too little, which is also a problem. There is probably hardly ever just the right amount of repression; so most of us are neurotic. Patients in psychoanalysis have either too much or too little repression. In both cases there is always some surplus demand, waiting and nagging to be metamorphosed into desire.

Here are two different but related ways of answering this question. The first is a bit abstract:

This conclusion may seem absurd because we are used to the idea that our desires are private, not public. Certainly we can hide our desires from others and from our own consciousness. But if I hide my desire from myself then it will find some other way of ‘speaking’. Desire always uses signifiers to express itself. Whether or not you are aware of it, or consciously willing, you will be spoken by your signifiers—and if you don’t speak them, they will speak you, in a slip of the tongue, in a dream or as a symptom.

Why did Lacan say that ‘desire is desire for difference?’ The object of demand is that which the other cannot give. So the child of poor parents might demand money from them, while the child of wealthy parents might demand that they tolerate his poverty-stricken appearance, ragged clothes and lack of interest in being respectable.

The orientation of the child’s demand is in the opposite direction to what his parents ask of him. This is because parents tend to resist some of their child’s demands, and so the child’s desire is always the efficient establishment of difference, in relation to his parents’ demand or desire.

LACAN’S THEORY OF FANTASY AND TRANSFERENCE

What does fantasy do? The most important function of fantasy is to help keep desire going. Desire is the stuff of life, the most important fact of human existence. How does fantasy help maintain desire? By fixing.

Usually a subject’s fantasies are dose variations on a single theme. Lacan called the underlying fantasy that generates these variations the ’fundamental fantasy’. Because the subject’s fantasies are all similar they have the effect of minimizing the variations in meaning, which might otherwise cause a problem for desire. Here is one example: if you desire your lover, but your lover is on the other side of the planet, what do you do? Why does your desire not disappear, in the absence of its object? How do you prevent your desire flagging? You wheel in a special mechanism: fantasy. You fantasize that you are with your lover.

So fantasy operates to keep desire roughly constant, to protect it from too much variation. Having your object of desire too far away is one problem: having it too close is another. Sometimes, when the object of desire has been too close, or present for too long, desire can begin to flag. Witness the fading of sexual interest that lovers often have in each other after years together. Desire in these cases can be maintained via fantasy. Typically such lovers fantasize—sometimes unconsciously—that they are having sex with someone other than their partner. Some evidence for this is the common use that lovers make of pornography. As Freud put it:

This leads us to another fundamental concept of Freud’s that Lacan developed—‘transference’.

‘Transference’ is a kind of translation. In transference an image or idea of the subject is projected onto someone else who is not the original love object. There is also a transfer of love or hate and supposed knowledge to a new person, of the sort that had Socrates put to death. If a man’s mother had a big nose, he may marry a woman with a big nose because he ‘mistakes’ his wife for his mother; he transfers or translates his love for his mother to his wife.

He meant that whenever there is love, there is always a mistaken identity, because when there is love there is demand, and demand is for something that does not exist. With the first love, between the motherer and infant, the powerless infant imagines that there exists some special object, something which will maintain his relation with the powerful motherer. All other love relations that follow from this first one seem to be based on it. Every consequent love relation appears to be an attempt to reproduce what the infant believes he once had in his relation with his motherer. What is this object, that is so important for infants, and what is its relation to desire? Lacan’s answer is that it is ‘a fiction’, something that does not actually exist except as a kind of convention, but that does not stop us looking for it!

The child’s demand is always addressed to an other, or m/other, to those who care for him, so the desire that grows out of the child’s frustrated demand is always in relation to others, and to the language of others, because it was the other who frustrated the child and fed him words instead of pleasure.

The child’s demand is always addressed to an other, or m/other, to those who care for him, so the desire that grows out of the child’s frustrated demand is always in relation to others, and to the language of others, because it was the other who frustrated the child and fed him words instead of pleasure.