CHAPTER 6

LACAN’S THEORY OF THE FOUR DISCOURSES

FOUR WAYS OF SPEAKING & BEING

Here is an example of people, apparently ‘communicating’:

What is ‘communication?’ Not the straightforward passage of language. It seems that there is always some addition, subtraction or variation, as the game of Chinese Whispers demonstrates. What people often do with language, it seems, is to misunderstand each other, especially in matters of love.

What is the relation of people to language? In Lacan’s theory the subject is divided, above all, by language. Language, as we have seen, fails each of us, and constitutes our subjectivity, that is what makes us human. Through language we misunderstand and are misunderstood.

The only way in which a subject can be undivided or ‘whole’, is for a very short time, by having jouissance, and we have seen that jouissance always comes in a package with problems, with suffering, conflicts and subjectivity.

In exactly what ways is the subject divided by language or discourse? Lacan believed that there are at least four different ways of being with language, four kinds of relation or discourse.

WHAT ARE THE FOUR DISCOURSES?

e’ve only got time to look at the slave-master discourse; it is the first and so the most fundamental of all four of Lacan’s discourses. Society could survive without the ‘discourse of the hysteric’, and that of ‘the analyst’, as well as without ‘the discourse of the university’, but we must be slaves and masters because we have competition, children and parents.

e’ve only got time to look at the slave-master discourse; it is the first and so the most fundamental of all four of Lacan’s discourses. Society could survive without the ‘discourse of the hysteric’, and that of ‘the analyst’, as well as without ‘the discourse of the university’, but we must be slaves and masters because we have competition, children and parents.

Lacan’s understanding of the slave-master relation was developed from Hegel’s theory. The main variables for Lacan are recognition, desire and jouissance. The slave, because of his subjectivity and loss, has some chance of reflecting and recognising his own desire: the master has far less chance of recognising his desire because he pressures the slave to recognise his demand for enjoyment. For Lacan the slave-master relation is universal, one in which we have all invested, either as slaves in some voluntary sense or as masters. As slaves we can enjoy the comforts of having a master, as a domestic pet does its human owner. As masters we can deceive ourselves about our desire by distracting ourselves with slaves whose purpose is to provide us with jouissance or enjoyment. This, to some extent, is the relation of parents to their child.

‘We live in a society in which slavery isn’t recognized. It’s nevertheless clear to any sociologist or philosopher that it has in no way been abolished....bondage hasn’t been abolished, one might say it has been generalized. The relationship of those known as “the exploiters”, in relation to the economy as a whole, is no less a relationship of bondage than that of the average man. Thus the master-slave duality is generalized within each participant in our society.’

‘The master has taken the slave’s jouissance from him, he has stolen the object of desire as object of the slave’s desire, but at the same time he has lost his own humanity. It was in no way the object of jouissance that was at issue, but rivalry as such. To whom does he owe his humanity? Solely to the slave’s recognition. However, since he doesn’t recognize the slave, that recognition literally has no value. The one who has triumphed and conquered the jouissance becomes a complete idiot, incapable of doing anything other than having jouissance, while he who has been deprived of it keeps his humanity intact. The slave recognizes the master, and thus he has the possibility of being recognized by him.’

Lacan argues that slavery and mastery operate universally in the mind and society. Democracy is a popular solution to political injustice but democracy does not eliminate slavery and mastery, it merely disguises it. In general people slave to be masters. Those who regard themselves as slaves suppose ‘their masters’ to possess knowledge and to have special access to jouissance. Many of those deemed to be ‘masters’ also promote the propaganda that they have knowledge and power, and hold the solution to the slave’s problems. The resulting slave-master relation is a collusion, a drama of compounded fictions. Each master is a slave to his own mastery. So the warders in a prison are a kind of prisoner too, confined in almost exactly the same way as the convicted prisoners.

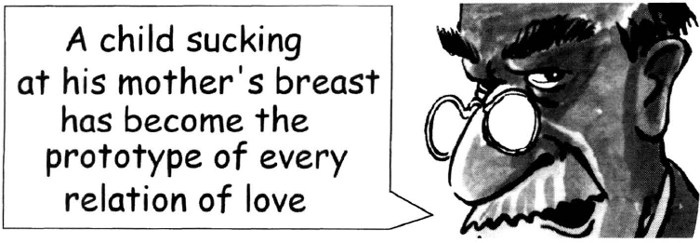

The idea and practice of being a slave is always entangled with the idea of being a master: the idea and practice of being a master is always entangled with the idea of being a slave. In the slave-master discourse jouissance is a central issue because infants and motherers both play at being slave-master, because the motherer-infrelation is the prototype for future adult sexual relations.

Slavery in the motherer-child relation arises from the suffering of pain by the child at what it understands to be the powerful hands of the masterful motherer. Who is in control of absence and presence in peek-a-boo games? Is it the baby as he gazes at the mother, then diverting his gaze, or is it really the motherer who actually has far more power to leave? For the baby, the motherer has the masterful position (she plays with her presence and absence by allowing her child a pretend mastery) but the mother may believe that her baby (which she chose to have) has made a slave of her.

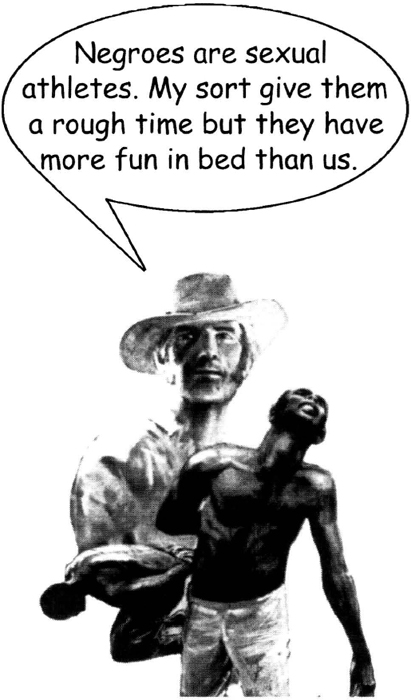

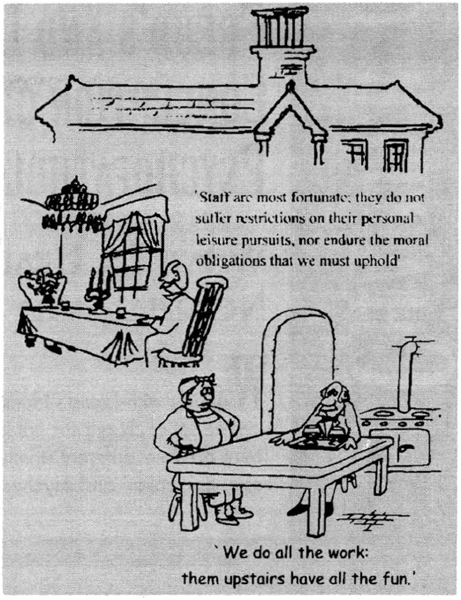

In a slight caricature: those who identify themselves as slaves, including prisoners, children, husbands, wives, employees, and those in any service industry usually believe that their master has all the fun, all the jouissance; while paradoxically those who identify themselves as masters usually believe that the slaves have a privileged access to jouissance. Sometimes slaves say that they are getting a fair deal but they will usually complain at the earliest opportunity and try to better their deal with their master.

One demonstration of the importance of jouissance in the slave-master relationship can be seen in submissive-domination sex enjoyed by so many, and in the popular erotic literature on the jouissance ‘of slaves and masters’ that details who takes jouissance from whom and how much. It is no coincidence that black people are sometimes regarded by whites as taking more enjoyment from sex than themselves.

Class divisions show a separation of the upper class and working class, both of whom believe the other to be stealing jouissance from themselves. Look at plays like ‘Oleanna’ (Mamet) or ‘Miss Julie’ (Strindberg) which dramatically switch around the roles of slave and master, or at the TV series ‘Upstairs Downstairs’. Each of these works illustrate the slave-master discourse: when the class or race barrier that holds jouissance in place is threatened by an interclass marriage, all hell breaks loose; the reassuring structure of mastery and slavery is in danger, as the economy of jouissance threatens a revolution.

Because slaves and masters have so much invested in the system that expresses and represses their desire, which both allows and forbids their jouissance, or their symptoms, it is common for both to show extreme loyalty or bondage to their slave-master culture. So much are the two entwined that it is often difficult distinguishing the slaves from the masters. This is one reason why revolution is so difficult to achieve: the oppressed have often become unconsciously invested in their repression.

Distinguishing slaves from masters is not possible. Nor is it possible, Lacan argued, to distinguish the healthy from the sick as we will see in the next chapter.