Psychosis is in some ways the most dramatic and extraordinary of the four clinical structures. What sorts of things do psychotics experience and do? Psychotics caricature the popular idea of ‘the mad person’ and are often unable to follow a career or intimate long term relationships for some or for all of their lives. A person suffering from psychosis will often have hallucinations of voices, and be uncomfortably conscious of being looked at—remember ‘the gaze’ and ‘the voice’ as examples of the little other?

CAN A SUBJECT BE JUST ‘A BIT PSYCHOTIC’, OR ‘A BORDERLINE CASE’?

Remember that Lacan thought your psychic structure would always be dominated by one of the four psychic structures: hysteria, obsessional neurosis, perversion, or psychosis.

You can’t be a bit pregnant, and, argues Lacan, you can’t be a bit psychotic, you either are or are not psychotic. This position is very different from Melanie Klein’s: she thought that we are all a bit psychotic, some of us more so than others.

This Klein-Lacan debate is complicated by two facts that often make it difficult to diagnose psychosis: the first we have already met; it is the problem of the same outward behaviour often having different underlying psychic structures. So, for example, some people, who are usually called by psychiatrists ‘manic depressive’, may appear to have some psychotic symptoms, while others may not. There are other examples of symptoms that can mimic psychosis such as hysterics who also hear voices and sometimes believe that they are being persecuted; so the diagnosis of psychosis is not always straightforward.

The second problem in diagnosing psychosis is that some people will lead their lives, apparently as neurotics, and then suddenly have a psychotic episode. For some psychotics, symptoms are not continuous, but may appear every few months or only once or twice in their lifetime—or even never at all! They have a neurotic layer or facade that lies over their psychotic structure. So it is possible, if nothing disturbs and triggers the underlying psychotic structure, for psychotics never to show any obvious psychotic symptoms for the whole of their lives!

This situation is a bit like someone who would be allergic to penicillin if they took it, but in fact they never have taken it. We would probably still want to say—assuming we knew—that such a person ‘is allergic to penicillin’, or would be, because they are capable, with their structure, of generating an allergic response to penicillin.

So there is a gulf between an underlying structure of neurosis or psychosis, and the symptoms or language presented by those underlying structures. It is therefore not straightforward diagnosing a structure as psychotic or neurotic because meaning in general is not fixed, but in flux. The difference between a neurotic and a psychotic is their language. Psychotics use language—or to be more Lacanian—are used by language in a different way from neurotics.

THE SYMBOLIC FATHER AND THE ‘NAMES OF THE FATHER’

The basis of this joke is the fact that while there is nearly always a question of paternity—as to who the father is—there is hardly ever a question of maternal identity. So your knowledge of your mother’s identity is relatively certain or fixed, while your knowledge of your father’s identity is far less certain and so is more likely to change.

With this mixture of paternity and identity in mind Lacan conceived ‘the Names-of-the-father’, which, he argued, has the special function of making psychotic structure radically different from neurotic structure.

Unfortunately, there is more than the Usual amount of guesswork required here, because Lacan never gave a course of seminars on the ‘Names-of-the-father’ as he did with many of his other ideas. To explain the ‘Names-of-the-father’ is not easy; we will need a detour around naming, the symbolic father, and the extraordinary work of the logician Kurt Godel, which will help to make sense of Lacan’s theory.

Lacan thought that to speak—to use language—you have to be separated from your motherer. If you are not properly separated from your motherer (by the ‘mother tongue’) then it will show in your language. What counts as proper separation? What is it in the separation from the motherer that allows the subject to speak? Lacan’s answer is ‘proper names’.

Lacan argued that the function of proper names allows a separation from the motherer, which in turn allows language. Without the special function of names we would not be able to speak and understand language, argued Lacan. Because psychotics have not been properly separated by names—from their motherer—they have a different relation to language, and a different way of speaking from neurotics.

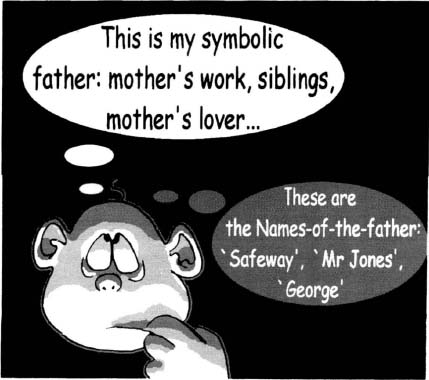

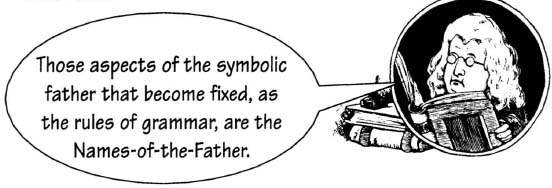

To make sense of this we should review Lacan’s concept: ‘the symbolic father’. A kind of separation of the child from the motherer is carried out by the symbolic father, which could be the motherer’s work, lover or siblings. But this symbolic father is not enough for proper and permanent separation that would prevent psychosis, because the identity of the symbolic father often changes, it is not fixed. So the separation of the child from the motherer would also vary as the identity of the separator—of the symbolic father—varied. What is required to prevent psychosis is a separation that is fixed and permanent. This permanence is a property of proper names, of the Names-of-the-father.

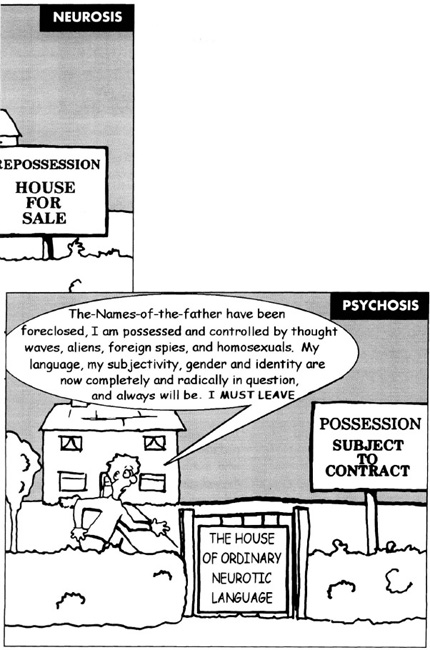

For neurotics the Names-of-the father are properly repressed and lie forever in the unconscious. But in psychosis the Names-of-the-father have not been properly repressed. To compensate for this lack of repression, psychotics introduce new identities into their lives that will then work to provide new repressions, that would otherwise be absent for them. These new repressions prop up their psychic structure and allow them to continue using language. What form do these new repressions take?

Often psychotics will speak about their being persecuted or controlled by aliens, of seeking asylum in a foreign country, or of changing gender.

In these cases there is the introduction of a new and conspicuous repressive identity that has the function of holding together language for them. These new and conscious entities have the function for psychotics that the Names-of-the-father have in the unconscious for neurotics.

HOW DOES THIS ‘HOLDING TOGETHER’ OF LANGUAGE BY THE PROPER NAME WORK?

We will look at two differences and a shocking revolution in mathematics and logic to help us make two distinctions: that between proper names and other words, and the difference between the symbolic father and the Names-of-the-father.

Let’s distinguish the Names-of-the-father from Lacan’s related idea, the symbolic father, who we met in chapter four. The symbolic father is any agency separating the child from the motherer. To find out how this Names-of-the-Father idea is different from the ‘symbolic father’ we should first look at some differences between proper nouns like ‘Fred’, ‘Smith’ and other types of word such as ‘table’, ‘house’, ‘white’ and ‘gay’.

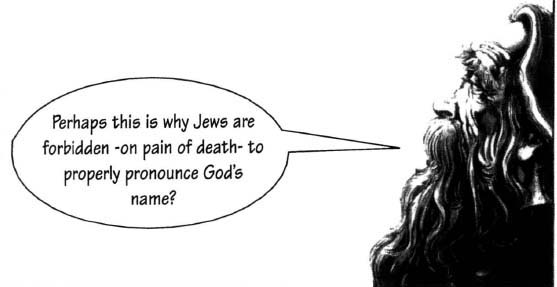

Take ‘gay’: it used to mean ‘jolly, happy’, but today it usually means ‘homosexual’, or ‘blue’ which at one time meant only a specific colour but now also refers to a mood of melancholy. But a proper name like ‘Fred Smith’ doesn’t change its meaning in the same way as a word like ‘blue’ or ‘gay’: ‘Fred Smith’ will always refer to the particular person or persons called ‘Fred Smith’, whatever happens to the English language over time. Proper names are forever glued to whatever they originally referred to. Lacan argues that there is a fixity about proper names that is absent in the other words in our language whose meanings shift. One type of fixed meaning are called ‘axioms’ or rules.

KURT GODEL’S REVOLUTIONARY INCOMPLETENESS THEOREM

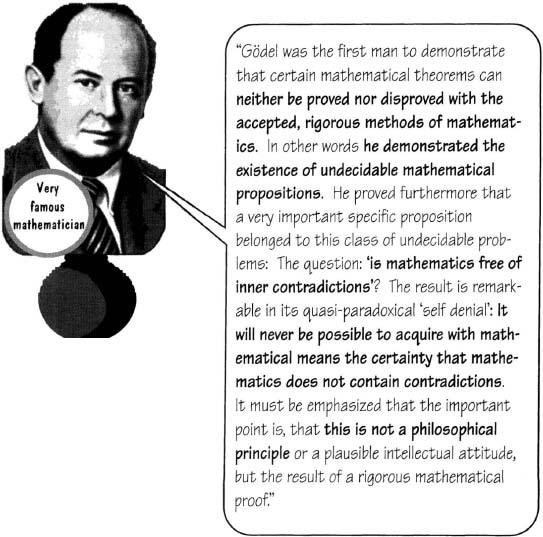

Kurt Gödel (1906-1978) was a logician and philosopher who is famous for having produced a logical proof about elementary number theory. He proved that there are rules that are true yet unprovable!

Before Gödel’s revolutionary work in 1931, it was taken for granted by all mathematicians that what was true could always be proved, and that everything would eventually become clear and proven, in just the same way that it was taken for granted after Newton’s discoveries, that we would fully understand all the workings of the world. But, as with Heisenberg’s work —which overthrew Newton’s tidy scheme— Gödel discovered a very surprising impossibility, a logically necessary impossibility, something that cannot be avoided. He destroyed the naïve and ideal conception of mathematics as ‘the true and provable’.

Put simply, Gödel proved that if you want to make a complete list of all the rules for making numbers, like a kind of grammar of numbers, then there are only two possibilities:

the list of rules will be incomplete, that is there will be some rules missing — which is a problem if you want a complete list.

there will be some inconsistency, that is there will be contradictions between some of the rules. Obviously if two rules contradict one another, it follows that they can’t both be true; one of them must be false. This is a problem because inconsistency is something that mathematicians and logicians avoid like the plague. It guarantees for them that there is something fatally wrong.

So Gödel proved that any system that is more complicated than counting must be either inconsistent (contradicts itself) or incomplete. And let’s face it, people can count and much more besides —we are much more complex than counting machines— so people must be ‘either incomplete or inconsistent’. How does this forced choice between inconsistency and incompleteness relate to Lacan’s theory of psychosis?

Put roughly, Lacan’s hypothesis about psychosis goes like this: for adults the generative base —that is the set of rules that produces language— is partially fixed. The generative base is like a grammar that produces all the different kinds of language and symptoms that each of us have. When we can use a language properly we can make a potentially infinite number of sentences, with every one of them grammatically correct, if we are not drunk or tired.

The underlying rules for generating all this extraordinary variety gradually become more fixed as children learn language. But it is probably true to say that there is a partially different set of rules for each person who speaks the same language. This would explain why we sometimes argue about the meanings of words.

When the fixed rules are laid down, as if they are written in stone, some rules can be fixed that are not consistent with each other, so that the rules contradict each other. For most people, for neurotics and perverts, the rules are not generally inconsistent but incomplete, that is, there are rules missing.

But for psychotics, the fundamental rules are contradictory; they have some fixed rules that are in conflict. So every pervert and neurotic lives his life with his own unique and changing incompleteness. But for the psychotic there are fixed rules that contradict one another, producing their very distressing symptoms of paranoia and hallucinations.

Where do the contradictory rules of psychotics come from? From the symbolic father, and from the Names-of-the-Father as we will see. But remember the relation that words like ‘table’ and ‘mean’ have in relation to proper names like ‘Fred Smith’? The fixity of proper names and the flux of adjectives and nouns are mutually supportive, and mutually dependent. They feed off one another. So it is with the symbolic father and with the Names—of—the—Father. The symbolic father is a thing in flux that changes because what separates the child from its motherer can change, but the Names-of-the Father are fixed, and once written can never be erased.

The fixity of proper names and the flux of common nouns and adjectives seem to be properties that rely mutually on one another. So proper names depend on the other bits of language, and the other bits of language depend on proper names.

For example, the symbolic father might be the biological father to start with, and then become a step-father, or sibling, and later be the motherer’s work.

But, while the identity of the symbolic father has been in flux, certain proper names have had their reference fixed. Perhaps with ‘Simon’, as the name of the biological father, ‘Fred’, as the name of the step father and ‘Safeway’, where the motherer works. So the child will have fixed some aspects of the symbolic father as proper names. It is these fixed rules that are the Names-of-the-Father.

The symbolic father may be more than ‘one thing’, such as ‘the biological father’, ‘the stepfather’, and ‘the motherer’s work’. But whatever bits make it up, the separation of motherer and child is seen by the child as the motherer’s desire for someone other than itself. The aspects of the symbolic father that remain in flux are not the Names of-the-Father.

Take the jobs of weaving and being a blacksmith. The meaning of ‘weaving’ is not precisely fixed; it might refer to weaving baskets, cloth or magic spells. Now think of the times when people were called after their occupations: Such as ‘Simon Blacksmith’ or ‘Helen Weaver’. Here you can see how nouns became proper names. In their passage to proper namehood, the nouns with variable meaning have come to have their meaning fixed; ‘Simon Blacksmith’ will always refer to a particular individual whatever ‘Blacksmith’ comes to mean as a noun, even thousands of years after he has died.

Lacan said that in psychosis:

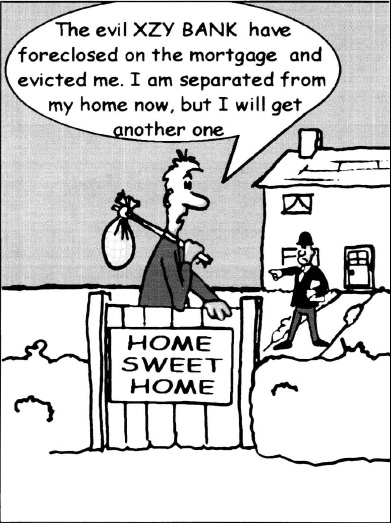

What does ‘foreclosure’ mean? Foreclosure is a kind of exclusion which occurs following the breaking of a contract. For instance when a mortgage lender forcloses on your mortgage, he excludes you from your home because you have failed to keep to the rules of your side of the contract with him.

All of us, psychotics and neurotics, have had a contract with the Names of-the-father. The terms of the contract are: as long as you do not speak the Names-of-the-father you will be permitted to live in the house of ordinary neurotic language. So, neurotics maintain their contracts with the Names-of-the-father while psychotics cannot.

How does the psychotic break his contract? He cannot gaurantee to keep the Names-of-the-father repressed and Unspoken.

Why? Because he has not been rigidly and properly separated from his motherer, so the rules of language and meaning are not properly fixed for psychotics. So when psychotics speak they always have some meanings that are far too fixed, and some that are far too loose, because the rules do not accord with the contract that binds neurotics. So when a psychotic was told that a messy room looked like a bomb had gone off in it, he jumped in fright, as if a bomb had literally gone off.

So if you have a mortgage on a house, and say ‘No, I can’t pay the lender’, the lender will ‘foreclose on the mortgage’. He will repossess your house and kick you out of it. Then the name of your lender will ring in your ears, as he who has separated you from your cosy home. In psychosis there is a price that the psychotic has not paid, and cannot pay. That price is the proper separation from the motherer, as marked out by the Names-of-the-father. Because the psychotic has not paid the price of separation from the motherer, language does not function for the psychotic as it does for the neurotic.

From a clinical point of view many psychotics are taken up in an extraordinary way with identity and with names. They may insist that they have been reincarnated and demand to be called by a different name, or wish to change their nationality, have sex change operations, or claim that a spell has been put on them that is changing their gender, identity and sexual orientation.

There is a clinical history often seen in cases of psychosis that involves either an absent and hence inconsistent symbolic father, or a very harsh or powerful symbolic father. We will see that these two sorts of symbolic fathers can amount to the same thing.

THE ROLE OF AN ABSENT SYMBOLIC FATHER IN PSYCHOSIS

ow it is time to relate Lacan’s theory to a clinical case:

ow it is time to relate Lacan’s theory to a clinical case:

It is not unusual for psychotics to have a history like that of a young man whose father left the family home when he was two years old. From that time until he was ten he slept in his mother’s bed, and did not know of any interest his mother had in any lover who had taken his absent father’s place. When he was seventeen he was persecuted by voices telling him that he was gay, and imagined that UFOs were communicating with him. These complaints completely dominated his life.

The inconsistency here is the presence and absence of the symbolic father, who, in this case also happened to be the biological father—not only the physical absence but also the symbolic absence; for the son had taken his father’s place in the matrimonial bed. Lacan’s hypothesis would probably be that this psychotic man had a pair of inconsistent rules, possibly along the following lines:

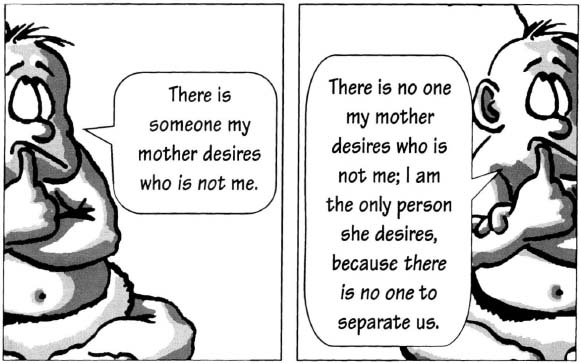

1. Up to age two, while there was someone—the symbolic father—separating him from his mother, he could say:

2. After his second birthday, when he started sleeping with his mother, there was no symbolic father separating him from his mother:

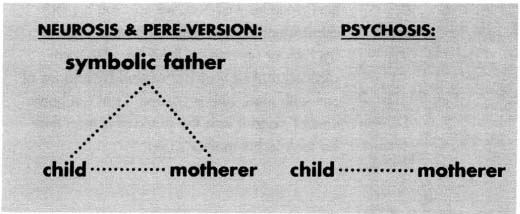

With neurotics and perverts there is a triangular relation between a child, its motherer and the symbolic father This triangular relation, with three rather than two people, which is also known as ‘The Oedipus relation’, ensures that the child is separated from its motherer, preventing the inconsistency described above from arising.

For psychotics there is a problem identifying the motherer’s desire for anyone other than themselves. They have failed to find anyone else whom the motherer desires. This often produces paranoia: grandiosity and ideas of persecution. Imagine, if you have someone who is enormously important in your life — your motherer— and you fail to find her desire for anyone besides yourself? You would be bound to see yourself as overly important; your world being totally dominated by one person and their desire for you.

In order to escape this vision of your life as totally dominated by this one person’s exclusive desire FOR YOU, you have a solution:

The idea of persecution introduces an other who takes up a position separating the subject from the motherer. In the case of the young man who had slept in his mother’s bed since he was two, we can see his thorough identification with his mother, that is, his lack of separation from her. He complained that he was persecuted by images of sex with men, and protested ‘I am not homosexual’; and it was the place of a man that he took in his mother’s bed.

But if the psychotic young man was to become a practising homosexual, then an important difference would become established: a distinction would be drawn between the young man and his mother, and they would then have become separate, because there would be a third person between them, because in fantasy the homosexual lover would be someone who both desired the young man, and was desired by the mother, so breaking the child-motherer duo.

For the young man, his feared object of love appears to be the same as his mother’s object of love, a man. This shared object of love would contrive the third element of the triangular or Oedipal relation that neurotics have, but too late to prevent psychosis.

In this case, the psychotic fantasies of sex with a third person, a man, caused torment, but seemed also to have had the function of preventing a more devastating break-down. The fantasy of the third person has the effect of preventing the inconsistency in the rules becoming apparent, by insisting —through paranoia— that there is someone who does separate the subject from the motherer.

As Lacan observed, the symptom is always a solution to a problem.

THE ROLE OF AN OVERBEARING SYMBOLIC FATHER IN PSYCHOSIS

Now it is time to explain how an overbearing, powerful and highly repressive symbolic father, such as a leader, can be equivalent to an absent symbolic father. Such a man is likely to be ‘too much’ for his children. He may, by being ‘too strong’ and highly repressive, increase the chance of having children who grow up to become psychotic. How can we explain this? By the fact that the father cannot possibly be present all the time. So that when he is absent, his absence is felt far more, again producing an inconsistency.

REPRESSION AND EXPRESSION IN AND OUT OF PSYCHOSIS

The idea of the absence or harshness of the symbolic father being important in psychosis is closely connected to Freud’s and Lacan’s theory of repression as learning. If we are to have an even chance of getting a mix of hysteria, obsessionality, and perversion, we should have an even amount of repression throughout our lives, without any peaks or troughs. So, in this unrealistic thought experiment there would be no traumas and no dramatic episodes of the sort that we have all experienced, just a thoroughly homogenous, bland, tame life.

What actually happens is that because repression varies, because we learn different things with different intensities, we each end up with one of the four different psychic structures: hysteria, obsessional neurosis, perversion or psychosis.

Psychotics, however have a kind of freedom, despite and because of their terrible symptoms. They can question in a more radical way than the rest of us, taking issue with things that most of us take for granted. Neurotics and perverts hove more that is rigidly fixed, that cannot be questioned.