Who are the greatest boxers of all time? Why—and how—did they become great? Are contemporary superstars such as Roy Jones, Jr., Bernard Hopkins, Oscar De La Hoya, Floyd Mayweather, Jr., Mike Tyson and Lennox Lewis better, or worse, than their counterparts of decades past? Why have certain eras produced an abundance of outstanding talent while others have not? This book answers these questions.

Anyone who has ever debated the merits of boxers from different eras knows there is a significant segment of the sports community who believes such comparisons are unfair. After all, aren’t the athletes of today bigger, stronger and faster than ever? Does it not make sense to believe that boxers are also bigger, stronger and faster than ever?

On a superficial level the “newer is always better” attitude towards athletic excellence appears to be valid, except for one important caveat; a boxer’s performance, unlike that of a swimmer, track and field athlete, or weightlifter, cannot be defined in terms of finite measurement. Boxing’s interaction of athleticism, experience, technique and psychology is a far more complex activity than just running, jumping, lifting or throwing.

To blithely state that today’s top professional boxers are better than their predecessors simply because measurable athletic performance has improved in other sports—whose winners are determined by a stopwatch, ruler or scale—is analogous to suggesting a singer is great only because he is capable of reaching a higher note than anyone else. Of course no reasonable person would agree with this statement because it totally ignores the complex nuances of the singer’s craft, such as timbre, inflection, vocal range and phrasing. Yet many people, without even realizing it, apply this same logic to boxing, oblivious as they are to the complex nuances of the boxer’s craft.

Even though today’s professional athletes are, on average, bigger than ever, it is illogical to relate this fact to boxers because they compete in separate weight divisions appropriate to their size. Except for heavyweights, the weight differential between opposing boxers rarely exceeds ten pounds. As for heavyweights, why should the “bigger than ever” label automatically stamp today’s giants as better fighters just because of their superior bulk? I challenge anyone with a modicum of interest in this sport to take a look at the four current heavyweight champions (whoever they are at the moment) and explain to me how they are better than the “small” heavyweights of 30 or 40 years ago, when fighters named Ali, Liston, Frazier, Holmes, Norton, Foreman and Quarry were contending for that once precious title.

Are today’s fighters stronger than ever? To properly answer this question one must first determine how strength manifests itself in a boxing match. In competitive weightlifting, the definition of effective strength is obvious; whoever can lift the most poundage always wins. On the other hand, a golfer’s strength is not measured by how much he can lift, but by how far he can hit the ball, and a tennis player’s superior strength is useful only if it translates into a powerful serve or return. If the stronger player is slower, less skillful, or lacks experience, strength becomes less of a factor in determining the outcome of a match.

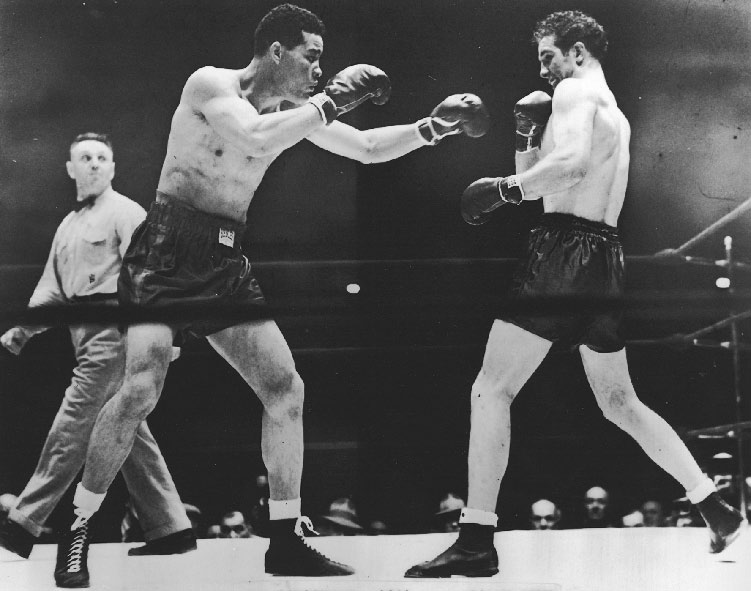

“He can run, but he can’t hide” was heavyweight champion Joe Louis’s response when asked about Billy Conn’s superior speed. Trailing on points, Louis (left) knocked Conn out in the 13th round of their 1941 title fight.

Strength is certainly useful to a boxer trying to control an opponent during infighting, or in a clinch. But it should be understood that strength and power are not synonymous. A fighter may be very strong but have only average hitting power, or he can be of average strength and possess a powerful knockout punch. Punching power is more important to a fighter than strength. Nevertheless, many fighters have achieved greatness despite having only average strength and hitting power. An example of this type of fighter was Depression-era champion Barney Ross. Many of his opponents were physically stronger and more powerful, but very few could match his consummate boxing skills, physical toughness and fighting spirit.

Notwithstanding his ability to stand up to the type of severe punishment that often took down much “stronger” men, Ross used strategies inherent within the art of boxing to counteract an opponent’s superior strength or punching power. He faced the best fighters of his time and won titles in three weight divisions while losing only four of eighty-one professional bouts. He was never stopped. How does one measure that type of strength?

The effective application of the art of boxing to defeat an opponent possessing superior strength and power was apparent as far back as 1892, at the very dawn of the modern boxing epoch, when James J. Corbett (“Gentleman” Jim) knocked out the legendary John L. Sullivan (“The Boston Strongboy”) in the 21st round to win the heavyweight championship of the world. This scenario would repeat itself countless times over the next century, as it did 72 years after Corbett-Sullivan when a fighter then known as Cassius Clay used a similar hit and move strategy to upset the brutish heavyweight champion Sonny Liston.

Although Corbett and Clay (soon to be renamed Muhammad Ali) were younger, faster and better conditioned than Sullivan and Liston, their intelligent use of speed enabled them to frustrate and eventually break down two of the most powerful fighters to ever hold the heavyweight championship.

Speed is a valuable asset for any athlete. Yet, as important as speed is to a boxer, it cannot determine the outcome of every match. A competent professional boxer can utilize a variety of tactics to offset an opponent’s superior speed. And—lest we forget—all the speed in the world will come to naught if a punch lands with enough force to stop a fast stepping opponent in his tracks. As Joe Louis so aptly put it before his heavyweight title fight with the lightning quick, but nevertheless doomed, Billy Conn: “He can run but he can’t hide.”

Today’s world class athletes routinely run a mile in less than four minutes and the hundred-yard dash in almost nine seconds flat, and can lift the equivalent of a small automobile off the ground—all of which is irrelevant to the sport of boxing. When technique, experience, strategy and psychology are thrown into the mix, an opponent’s superior speed, strength or power are situations that a competent boxer must deal with and attempt to overcome.

Another dimension that cannot be measured with a stopwatch, ruler or scale involves the character of the athlete. Character, or as it is known in the boxing vernacular, “heart” (and during the English bare-knuckle period, “bottom”), is important to any athlete aspiring to greatness. But the word takes on added meaning when it is applied to professional boxing. “We are not speaking here of simple courage. Any man who ties on the gloves and walks into the ring has a degree of courage,” wrote Pete Hamill on the subject of heart. “To say that a man had heart was a more complicated matter. The fighter with heart was willing to endure pain in order to inflict it. The fighter with heart accepted the cruel rules of the sport. He must not—could not—quit. He might be outclassed and outgunned but he never looked for an exit.”1

Few heavyweights of any era could match Mike Tyson’s tremendous punching power. Athletically, he was blessed with all the tools for boxing greatness. If his talent was for basketball or football his character flaws would not have affected his performance nearly as much, and he would have maintained his lofty status. But professional boxing is different; it asks questions of its athletes that other sports do not.

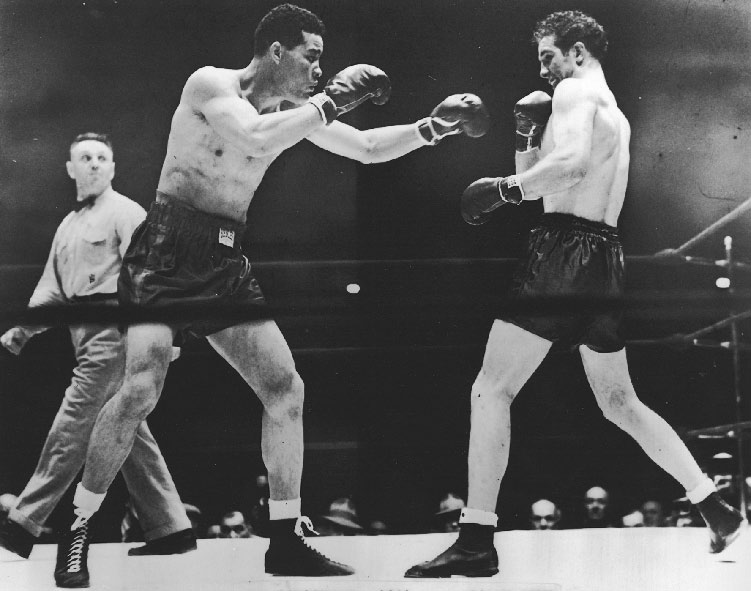

Legendary Depression era boxing rivals Barney Ross (left) and Tony Canzoneri square off in 1933 (courtesy Stephanie Arcel; from the Archives of Ray Arcel).

When confronted with an opponent he could not overpower, Tyson became frustrated and his fragile confidence wavered. His vaunted “killer instinct” appeared to fade in the later rounds. Too often he welcomed the respite of a clinch. In extreme situations he either stopped fighting or sought the nearest exit by fouling out. Although Mike Tyson possessed the physical attributes of a great athlete, he did not possess the psyche of a great fighter. Evander Holyfield defeated Tyson as much with his character as with his fists. Whoever said “character is destiny” must have had the unforgiving sport of boxing in mind.

These are just a few of the topics to be discussed on the path to boxing enlightenment it is my sincere wish this book will provide.

A final note: When a lawyer attempts to make the strongest argument possible on behalf of his client, he requires the testimony of credible witnesses to bolster his case. To enhance this book’s validity I have included the testimony of three of the world’s most renowned teacher-trainers: Teddy Atlas, Emanuel Steward and Freddie Roach. Over a dozen other experts—among the sharpest minds in boxing—have also contributed their insights and opinions. Some of these experts are old enough to have personally witnessed the best fighters of the past 70 years. This may be the last opportunity to delve into the wealth of information and knowledge they have to offer concerning the “Old School” vs. “New School” boxing debate.

All of the interviews were conducted independently—one on one. The reader will undoubtedly note a similarity in many of the views expressed. A conscious decision was made not to edit out the overlap, for it is the very consistency of these independent opinions that lends strength to their truth.

I have spent over 40 years seeking out and meeting with top boxing experts, documenting conversations, and gaining insights. The information contained in these pages challenges many preconceived notions about the nature of boxing as it exists today. Whether you agree or disagree with the book’s conclusions, of one thing I am certain—no one who reads it will ever look at a boxing match in the same way again.