Thirty years ago, or even 20 years ago, a boxer was around four, five years before he got to be a main eventer. He’d have 50, 75 fights before we thought of putting him in a main event.1

Trainer quoted in September 1956 issue of The Ring magazine.

In 1991 Bob Foster, light heavyweight champion from 1968 to 1975, was asked if he thought he could have beaten Michael Spinks, who held the same title a decade later. “I would have beaten him,” replied Foster, “because Spinks had too much amateur in him.”2 Foster’s “too much amateur” remark stands as a fitting description for the vast majority of today’s contenders and champions.

I can no longer tune into a televised fight that is already in progress and quickly determine if I am watching a preliminary bout or the main event. So many of today’s headliners look and fight like preliminary boxers it is impossible to tell the difference.

Since the 1990s the line separating top amateur boxers from top professional boxers has become blurred. There exists a hint of lingering amateurism in the fighting styles of Roy Jones, Jr., Antonio Tarver, Corey Spinks, Zab Judah, Floyd Mayweather, Jr., Vernon Forrest, Vladimir Klischko, Jermain Taylor, and a gaggle of other lesser-known belt holders and contenders. Body punching, bobbing and weaving, infighting, feinting, timing and mobile footwork are among the lost boxing arts. These skills are rarely seen today, even among champions considered superior boxers.

Amateur boxing has to take some of the blame for what has happened to the quality of professional boxing over the past two decades.

Amateur boxing is governed by international Olympic rules. These rules encourage a long-range stand up style of boxing. Body punches are rarely thrown because they do not count in the scoring. Amateur rules do not allow bending, ducking or weaving, as that could lead to unintentional head collisions. An amateur fighter using these moves risks a point deduction. Clinching or tying up an opponent is also disallowed.

On the plus side, amateur boxing emphasizes safety. Most fights are limited to 3 rounds and competitors must wear headguards. The referee, at his discretion, can administer a standing eight count or end the bout if a boxer appears overmatched. Skillful boxing is encouraged and rewarded. A knockdown counts no more than an accurate jab in the scoring.

Aside from trying to create a safer environment, amateur officials also want to distance the sport from anything reminiscent of the sleazy professional boxing world. But in their zeal to create a safer and cleaner image for boxing, they have taken away many of the fighter’s traditional tools, including body punching, infighting, clinching, bending, ducking and weaving.

Prior to 1976 amateur boxers planning to turn pro were not as concerned with mastering the international style. That attitude changed after Sugar Ray Leonard and his gold medal winning Olympic teammates received lucrative television contracts.

Insiders and observers say too many fighters are stuck in the amateur mode of competition, although they are competing as pros.

Emanuel Steward: “A lot of today’s fighters are still doing the amateur things. In the past amateur fighters who turned pro went to professional trainers. You had the Charlie Goldmans and the Ray Arcels—the guys who taught them the tricks of the trade. What’s happening now is that the amateur kids are staying with the same coaches. A lot of them are not making the transition to becoming professionals because the coaches themselves can’t make the transition. So a lot of the kids in the pros are still fighting like amateurs.”

Mike Capriano, Jr.: “Today most fighters turn pro with a similar stand up style because the scoring under international amateur rules does not count body punching. So the boxer that weaved and was able to get under the punches is discouraged from doing so. Everyone turning pro is a stand up fighter, or close to it. They all have a certain type of style, which is common today. If they had fought in the 1930s or 1940s they would be facing different types of styles, which they’d have no experience with. They’d have problems trying to adjust.

“Usually where amateurs trained there were also very skilled professional fighters. A young fighter had the advantage of watching the pros train.”

Teddy Atlas: “Some of these kids today do have a lot of amateur fights and they do get experience in that way, but what happens next is that when they go into the pros it’s almost like they’re going into a non-competitive environment. It’s like going from tackle football to flag football. When they go into the pros they’re navigated so much that any theoretical advantage they may have gotten from their amateur experience, especially if they were on the top level nationally and internationally, is lost.

“It really is like going from playing full equipment football to suddenly playing flag ball, because now they are going in the opposite direction. They are consistently matched with inferior opponents and the result is that any development that was gained in their amateur careers, that was there for them to continue to improve upon in the pros, is lost. They are not forced to face reality. They are not forced to face decisions and have urgency in the ring and in their career.

“They’re like a turkey that’s put out on a farm for a year to just eat the best food until their head is chopped off for the freakin’ dinner. You know what? That’s actually a pretty good analogy, because they go from amateur, where they might have had 160 fights, to the pros and the first thing the manager does is start buying fights for him, making sure that they’re non-competitive. They actually make sure that they don’t have any competitive fights while they are building up his undefeated record.

“If you try to make a comparison to this era and 50 or more years ago it’s a joke because the old time guys, wherever they were getting experience, whether it was in the pros, or the amateurs, that experience was competitive experience at the time that it counted the most—in the formative years. They fought competitive fights.

“Why do you think a fighter like Francisco Bojado, a guy that was supposed to be the next star, blew up to 160–170 pounds and then lost to an ordinary opponent that he was not supposed to lose to? It’s because of what they were feeding the “turkey” when he turned pro. Do you think he can have the mental conditioning that the old timers had? Do you think there is any comparison to the mindset of a Bojado and another fighter from an earlier era? He may not have had the same number of amateur fights as Bojado but he had those competitive pro fights, perhaps a hundred or more. There’s no comparison. Those guys would have eaten Bojado and spit him out because they were getting conditioned for what the business was about. They were fighting those kinds of fights. “You take an amateur kid today and feed him ten or twelve easy pro fights—you cannot tell me that you’re on the same plane as the fighters we are talking about. That’s the difference, and that’s a huge difference.”

Freddie Roach: “A boxer learns the fundamentals in the amateurs. When I was an amateur, in the 1970s, we fought under professional rules. When we would go to the national tournaments it was under International rules and we’d get disqualified for bending too low and making the punch miss, which is something I was taught to do.

“Bobbing, weaving, and body punches do not count in the amateurs. All you can do is block the punches by putting your hands in front of your face. What kind of defense is that? In the pros it doesn’t make sense because you want to slip a punch and counter. When you slip a punch there is always the opportunity for a counter. If you don’t learn that as a young amateur it becomes hard to change later on. By the time a fighter gets to the championship level in the pros many are still putting their gloves in front of their faces but not attempting to slip the punches.

“Part of the problem is that you’ve lost the pro coaches. To me the amateurs were at one time like pre-school for a professional fighter in learning his trade. But with the new scoring system in the amateurs it’s a whole different sport. So when you turn pro it’s almost like you have to forget everything you’ve learned as an amateur in order to change into a pro style and it is very difficult to get someone to change.

“Body punching is a lost art today. They don’t score body punches at all in the amateurs. In the pros they should score it—they are supposed to—but a lot of judges just look for the headhunters. There is no bodywork anymore. I think that’s the biggest thing missing in boxing—knowing how to break a guy down with a body attack. These fighters back in the 1940s, and ’50s, they’d work the body and by the eighth, ninth, 10th round these guys’ legs would be gone. Body shots take a lot out of you, unlike headshots, which you can recover from during the course of a fight. Headshots may put you on ‘queer street’ a little bit—body punches kind of stay with you the entire night. They take their toll. So that is missing, along with the numbers of fighters, the quality professional trainers and the role models to learn off of.”

Wilbert “Skeeter” McClure: “I had 148 amateur fights. I turned pro after winning a Gold Medal in the 1960 Olympics. My first 4 pro fights I didn’t clinch because in international amateur competition you don’t clinch. The referees will penalize you.

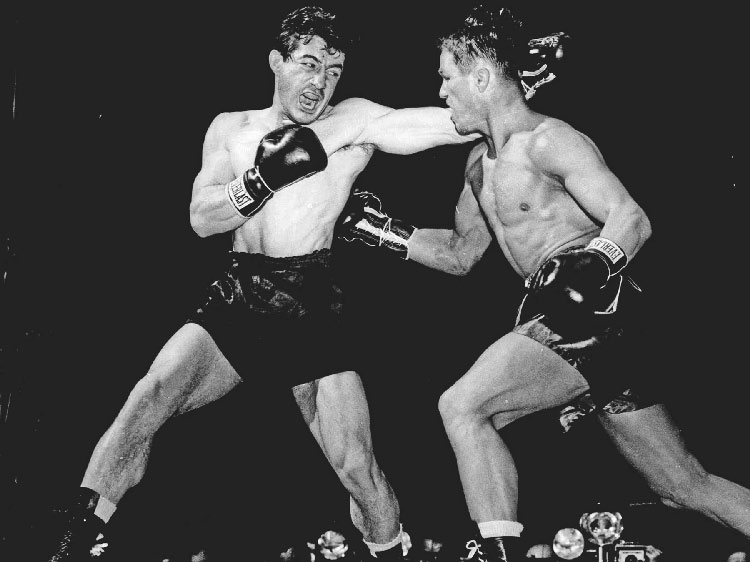

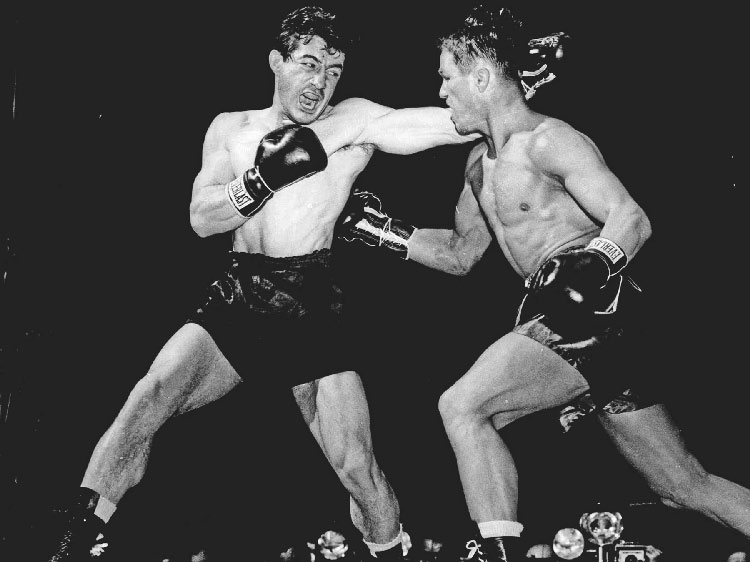

Tony Zale (right), a serious devotee of the (now) lost art of body punching, lands his favorite punch on Rocky Graziano during their 1948 middleweight title fight, won by Zale on a third round KO. (AP Images/Wide World Photos).

“The main difference between amateur and professional fighting is the distance and how tough and savvy the fighters are in the pros. Like they foul you in some interesting ways. The amateurs are clean, clean, clean. But in the pros you learn that it’s a war out there. They are going to grab you, yank you, push you, step on you, and foul you deliberately. You’ve got to be prepared for that, and that’s what I was learning.”

Teddy Atlas: “Very rarely do you see inside fighting today. Fighters are not at the level to be able to know how to do it and the trainers are not there who would be able teach it. But even if a fighter desired to fight on the inside the referees today don’t allow him to.

“In the old days the referees were developed as real referees. They understood what was going on. The referees knew when a guy was not clinching. They understood that he was getting position. The referees did not panic and break the boxers apart right away, as they so often do today, and have the boxers go outside to avoid that kind of fighting. They didn’t tap him and say ‘get out of there.’ They watched and let him do his thing, and ply his trade.

“Those old time fighters were magnificent in the way they knew how to maneuver on the inside. There were so many aspects to it. If you understood what was happening you could see that when it looked like a fighter was tiring, what he was really doing was moving his arm underneath the other guy’s arm so he could hit him with an uppercut. And when his hand was on top, over the glove, all of a sudden it went underneath, and the next thing you know he’s got his shoulder in there and he’s hitting him with a punch, or turning the guy’s elbow to maneuver him into a punch. You’d see a fighter push his opponent so the other guy would start to push back and then all of a sudden he’d pull back and walk him into something.

“It was a science. It really was the ‘sweet science.’ That writer was right. I’ll bet you he watched inside fighting when he thought up that phrase. I bet you the writer who said that—I think it was Liebling—I’ll bet you he was watching a fighter who knew how to fight on the inside. When you ask about the lost techniques, the inside gift, the inside science, that’s where I go.”

Chuck Hasson: “‘CompuBox’ never counts body punches. I’ll see a guy that’s directing his attack to the body and at the end of the round the announcers report that according to the ‘CompuBox’ count he landed six punches. Well I saw him land 15 to 20 body punches but they don’t even detect these punches.

“I loved to watch body punching and inside fighting. I especially enjoyed the way the masters would maneuver inside. Despite being where all the danger is, they would be slipping, sliding, moving their head, and blocking with their arms shoulders and elbows. I love the art of body punching and infighting. But you don’t have the master trainers to teach a fighter how to do either. And today’s fighters are being pushed into 12 round bouts without having fought enough sixes and eights. It seems like every fight is a 12 rounder.”

A good boxer in the Golden Age would look for mistakes—and even try to tempt them from an opponent—and then take full advantage. They adapted to the style of an opponent as a match progressed.

Tony Arnold: “There’s another problem today’s fighters have—they don’t know how to capitalize on another fighter’s mistakes. You see it time and time again. They know to throw a jab and then follow with a right hand but they cannot see a mistake and then know how to capitalize on it. Like the way Archie Moore used to sucker a guy into a right hand lead. Archie was ready with his own right hand counter, or he would come inside the opponent’s right lead with his left hook. How do you think he knocked out Bobo Olson?

“Archie was a master at drawing leads. He’d expose one side of his head so you’d throw a right hand or he’d lean to the left so you’d throw a jab. How many fighters know how to do that today? If you draw a lead you’re making the opponent do something that you are prepared to counter. Who teaches that anymore? That’s a lost art. That’s a skill of a master fighter. And they could do it so subtly you don’t even know they’re doing it. Many times a fighter would purposely drop his left shoulder or drop his left hand to expose himself to a right hand lead because he wants that lead so he can counter punch. These are the skills of a seasoned professional fighter.

“There are so many things that are lost today it’s incredible. Guys call themselves trainers and teachers but they don’t teach the fighter ring generalship or the tricks of the trade. They think a trick is stepping on the other guy’s feet, but there’s a lot more to it than that. You want to make the guy fight your fight. A master fighter can do that—not just to try to meet the guy in the center of the ring and hit him harder than he’s hitting you, or beat him to the punch. You try and make things happen.

“Maxie Shapiro, a 1930s era lightweight contender, was a master at ducking, weaving, and sliding with a purpose. He knew an opponent was going to throw jabs or straight rights at him if he moved his head a certain way. That’s real skill—making the other guy do what you want him to do. So many things like that are missing today. When you talk about the different eras of fighters you have to take that into consideration.

“Golden Age fighters didn’t just go into a fight and say, ‘I’m going to knock this guy out,’ or, ‘I’m stronger than him and I’ll overpower him.’ They did not go in with that attitude. The attitude was, ‘I’m going to make this guy do what I want him to do. I’m going to make him fight my fight. I’m not going to fight his fight.’ And the real good fighters could do that. They would make the fighter chase them. Sugar Ray Robinson was the grand master at that. He could knock you out going backwards. He would retreat so the guy would come in faster on him and then he’d pop him as he was coming in. Look what he did with Gene Fullmer in that second fight. Robinson was a faded old man then but he set him up for that left hook so perfect you could see it coming. Fullmer was always coming in with those wide right hand swings to the body and Robinson let him do it many times and he would block the punches with his left forearm, and sometimes he’d take the shots. And in the fifth round Fullmer came in again with the wide right and Robinson stepped in with a perfectly timed left hook. That’s a master executing a move.

“Archie Moore did the same thing in his last fight with Harold Johnson in 1954. Johnson was winning the fight. He had Moore down. But Moore couldn’t quite catch him, couldn’t quite get his rhythm. Johnson was scoring points and boxing beautifully and Moore was frustrated. Johnson was too quick and too smart. In the 14th round Archie came in slow for the first minute and suddenly, when Johnson jabbed, he sprung in with his right. Archie was timing those jabs. Johnson was becoming so confident because Moore was just standing at the end of those jabs. This is just one of the thousands of things a great fighter could do. They talk about Holyfield and Michael Spinks as great fighters but they didn’t fight that kind of fight.

“Bob Foster knew how to set up his left hook. The problem with him is that I don’t think he could have survived Moore. He had the perfect style for Moore in that Foster’s half crouch would play right into Moore’s right hand. It would just be a question of time. Foster was a helluva fighter. The problem was his durability. Speaking of durability, look at Billy Conn. Nobody but Louis could knock him out.

“I’m not just being kind of sour grapes because it’s not my era. You can see it. I mean there were guys in the 1960s and ’70s, even in the ’80s that were really skilled fighters. Wilfredo Benitez was a fine fighter, he had a lot of natural skills. He was a young fighter, yet he could hold his own with veterans. Marlon Starling was a good all around fighter, as was Wilfredo Gomez. It started fading, I think, around the 1990s. Things got worse.”

Mike Capriano, Jr.: “Different styles—that’s what made the business. In the 1920s, during the prolific era of New York’s Lower East side lightweights, intelligence was important. Benny Leonard was a tremendous influence in every weight division. The Benny Leonard style of setting you up for knockout punches was taught then, as was the correct way to tie up an opponent.

“Leonard’s style was to outbox you and look for a spot—cross that right hand, or drop that hook or uppercut. There was not a mark on him. Charley Burley was similar. He’d move around throwing fast punches and size you up as he looked to knock you out. Henry Armstrong learned to slip punches and move you back, which exhausted the fighter moving back.

“There are no super skilled boxers like Tippy Larkin, Billy Graham, or Maxie Shapiro. I don’t see them around. There were many different types of fighters and you’d see many different styles, and that’s probably what made them better fighters.

“I don’t see anyone with that type of skill today—in any weight division. Some of today’s fighters look good, and they seem to have the natural instincts and maybe somebody is teaching them but I still don’t see the moves. They need more seasoning.

“You don’t see a fighter bend and weave in anymore. I mean we might see somebody bob back and forth and move in but that is not your classic bend and weave move. Even Tyson never did that. He’d bob back and forth but he just distracted you, and then he’d throw those overhand punches. Tyson bulled his way in. He bobbed, but he didn’t weave. He tried to overpower you. And when he couldn’t overpower you he got stymied. Tyson really had no moves.

“We don’t see fighters today sliding in. We don’t see the feints, the hook off a feint, step to the right and uppercut, moving, grabbing the elbow and spinning the fighter. We don’t see any of that today because it’s gone and nobody knows how to teach it. You don’t see any of these fighters making the same moves as the old time fighters—absolutely not. The fans today never saw these fighters.

“Of course there were also fighters who were crude and strong, or had great endurance, but were not as skillful. But the difference between then and now was that the old timers knew how to use their endurance and strength. So if you weren’t such a great boxer you knew how to utilize what you had in order to win. There are fighters today who also are very strong and have endurance but they don’t know how to utilize these assets.

“I’m not preserving any situation where my status is better than anybody else’s. I’m not doing it to lie. I’m telling you what we saw and what we know. There is such an agreement by those that were there and observed. Sure, there could be upsets if some of the old timers were matched up against today’s best, but I don’t think so.

“Craftiness is missing. Moore was crafty. Dempsey was crafty. Duran had great instincts and was crafty. Not feinting, no body punches, and no craftiness—these are the hallmarks of today’s top fighters. Looking back over the years I have to say that the farther back you go, the better the fighters are.”

Teddy Atlas: “I still see fighters from the 1930s and 1940s. I have been privileged to see the films. Not everyone gets to see them. Those old timers are doing things that I still do not see today’s guys doing. Whether it’s judging distance better, or jabbing an opponent’s shoulder to distract or unbalance him, or letting an opponent think he’s safe when he’s not safe, or doing a feint for more than just motion but actually to make something happen. So many subtleties are missing. I’d just love to hear the trainers talk about the old timers. They’d say things like, ‘He’d feint you and make you bend down and tie your shoelaces.’”

Bill Goodman: “The fighters all look the same because they are not groomed properly. Conditioning the fighter with strength training and other forms of physical work has taken the place of real teaching. The Russian pros all fight the same way. Most of them have extensive amateur backgrounds and they all fight using the stand-up Olympic style. The fighters are uneducated. But it’s not their fault. They are not being taught properly. “I never see a sharp, varied attack; slipping, blocking, sidestepping, moving on good legs with good balance and using an active left hand properly. They throw a jab and they stop. It’s a big deal if they throw two in a row.

“A seasoned pro can adapt his style to avoid punishment. You used to see fighters adapting fast to avoid punishment. Today it’s all the same, minute after minute, round after round. If you see one round you saw the whole fight. You can go home. One round is the same as the other round. They don’t have variance in it. They all fight the same way. You saw the guy fight once, even if he’s fighting the same opponent he fought previously, he’s going to fight the same way.

“There are little things they could do to make it more interesting. Ninety-nine percent of the time the fighters don’t move off from punching, which makes them too easy to hit after they’ve delivered their volley. The fighter walks in, throws a few punches, gets lucky and hits his opponent. But after landing his punches he should slide out, or spin out, and move off to his right. That move allows you to get off again. You’re too easy to hit when you stand in the same place. Even if you slide back a little bit, it’s not enough. You’ve got to move off of punching and keep moving. That’s the secret of the matter—keep moving. But the fighters don’t know how to use their legs to keep moving. They don’t know how to spin out to another position after throwing a volley of punches. Spinning is a forgotten art. Who spins today?

“Fighters are not being taught to use their legs properly. They don’t know how to bend either. You also never see guys practicing to develop coordination between the arms, legs and body. They used to teach that all the time. Fighters would practice for hours to perfect coordination between arms and legs so they worked as one. They don’t develop that, so how can today’s fighters look like those of yesteryear when you don’t see that? Watch a fighter shadowboxing in the dressing room before a TV fight. You see the arms moving but not the rest of the body or the feet. They stay in one place. It’s all hands, hands, hands. There is no coordination or synchronization between the legs and the arms.”

“I can’t blame the fighters. The ability is there. They have the potential to be much better than they are because the ability is there. You can make a fighter out of some of these guys but nobody shows them. They think they’re showing them.”

The finer points of boxing are also now mostly lost on fans, too, the experts say.

Ted Lidsky: “If today’s fans were shown some full-length films of Sugar Ray Robinson, they’d think it’s something different and unusual, but they wouldn’t understand what he was doing. It’s a different language.

“There’s always been ‘fighting’ but boxing was something different. I very rarely watch fights anymore these days. I can’t watch an entire fight. It’s kind of depressing to watch. But if this was what boxing was when I was a kid I would be embarrassed for having spent so much time watching it because it’s nothing but brutality. There is no beauty in this. It’s fighting, nothing else. There used to be skill and grace in conjunction with the brutality. Even sluggers were smart. Take a look at Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter. He didn’t take a punch to land a punch.

“You know, we’ve had discussions about people being actually knowledgeable about boxing. If you watch fights nowadays as a fan, if you can sit through an entire fight then you don’t know boxing. I don’t care if you know statistics. I don’t care if you could give me the history back to the Romans, you don’t understand boxing itself. If you can sit and watch this thing, what boxing has become, and what fighting is, then you don’t like boxing. You like fighting. You like brawling. And it’s not the same thing. If you compare what boxing once was and what it has become, this is checkers in comparison to chess.”

Tony Arnold: “Even if you take a lot of people today and have them look at films of great fighters of the past, they still wouldn’t know what they are looking at. They wouldn’t understand the moves. The problem is people don’t have the eye to see the good and bad points. They’ll only see the obvious, which is natural unless you’re really into the business. Mike Tyson walks in with a wild roundhouse swing and knocks the other guy flat—that they can understand. But a Joey Maxim smothering a guy’s punches, and slipping and sliding, and staying out of trouble by stabbing a guy with jabs and then sidestepping his rushes, they wouldn’t understand.

“Somebody watching films of Willie Pep might say, ‘Oh he runs all over the place.’ They don’t see what he’s doing in there, how he switches gears, how he starts to the left and then swings around to the right almost in the same motion. I’ve never seen anybody be able to do that. Pep was not only a moving target, he was a target that was moving from all angles. He wasn’t just moving, he was moving with a plan. The plan was to constantly keep you off balance, so you didn’t know where he was going to be from one second to the next.

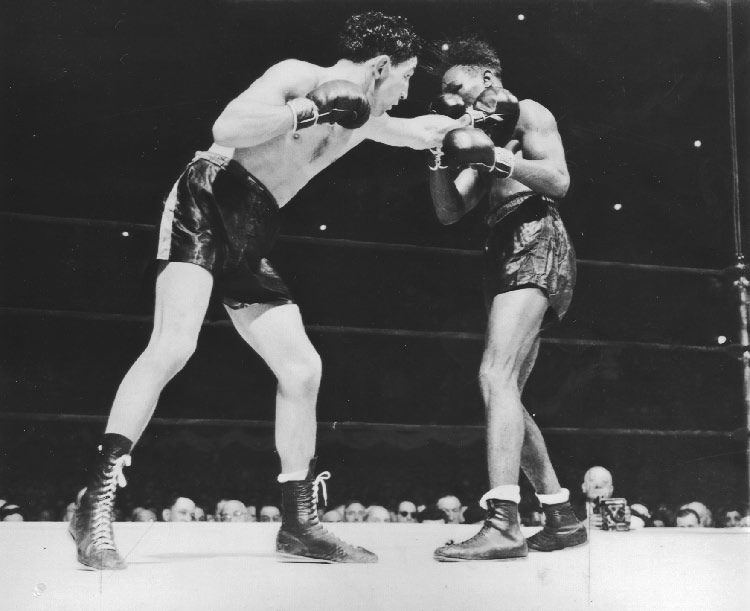

“Fighting Willie Pep is like trying to stamp out a grass fire,” said one opponent after fighting the elusive “Will-o-the-Wisp.” Pep (left) jabs the great Chalky Wright in 1942. Pep combined speed with brilliant boxing technique to win 229 out of 241 pro fights (The International Hall of Champions).

“Pep was always within punching room, hitting you with jabs, and coming up behind you, and moving side to side. Pep was always moving with a purpose. He wasn’t just flying around the ring. A lot of people wouldn’t see that. It depends on who’s looking at the fights.”

Chuck Hasson: “Today it is so much flash and everything is built on speed, whereas in the old days there were subtle moves that you just don’t see anymore. Head feints, eye feints, shoulder feints, body punching. Teddy Yarosz, who was middleweight champion in the mid–1930s, had a boring style but he was a master at out-maneuvering an opponent and having him do what you wanted him to do. It might not be fun to watch but it was effective and it won fights.”

Bill Goodman: “All that’s required today is a guy that can stand up. You showcase a guy with a good chin that stands up and he is accepted. Years ago you needed more than that. Today that’s all you need. Nothing. You’re a fighter.”

Tony Arnold: “My trainer, Willie Grunes, used to tell me if you can avoid blocking a punch with your gloves, do so. Slip inside, slip outside or slip under it and counter punch. Because if you are busy using your hands to defend yourself, you might not be able to hit your opponent back fast enough with a counter. So you keep your hands free. That doesn’t mean you never block punches with your gloves. I mean you’ve got to use common sense. But if at all possible, particularly when you are on the ropes you want to keep your hands free to punch.

“Fighters today get trapped on the ropes and all they do is try to cover up while the other guy’s pounding away. You see it all the time. But I never hear the announcers say, ‘Why isn’t he slipping and sliding; why isn’t he ducking; why isn’t he trying to tie the guy up; why isn’t he sidestepping? Why isn’t he countering?’ I never hear any of that.

“When a fighter’s back is to the ropes and he goes into a shell it automatically triggers an attack in his opponent’s mind. He’s going to swarm into you. If you’re in that position on the ropes you’re basically saying to your opponent, ‘Come and execute me.’ But what you should be doing is looking for an opening. You shouldn’t be thinking ‘I’m on the ropes, I’m trapped.’ You’re not trapped. Your opponent’s coming into your web. You don’t keep your hands rigid. That’s like having a gun in a holster. What good is it doing? You’ve got to have those hands free. When your opponent comes in, if he throws a left hook, or a straight right—or whatever—you slide, you bob and you bang in two or three counters. Pretty soon he’s saying, ‘What am I doing? Who’s on the ropes, him or me?’

“You use the ropes. You can use the ropes to support your back as you slide and slip and throw counter shots. That way you’re not in a defensive position. And if you’re countering him and hitting him good, when you see you have a chance you can spin him off and get him on the ropes, or get out to the center of the ring, and you haven’t taken too many punches. But what you don’t want to do is lay on the ropes and hide behind your gloves.”

Erik Arnold: “Today’s fighters don’t know how to avoid punches. When they are hurt they either grab and hold onto their opponent or just put their back against the ropes and wait to be executed.”

Unlike their Golden Age counterparts, one rarely sees today’s professional fighters—from rank novice to multiple belt holders—duck, parry, slip, sidestep, ride, weave or roll to avoid punches. Most walk into punches. The emphasis today is on aggression, strength and punching power. Defense is given short shrift. Television encourages this type of fight because it appeals to the broadest possible audience. As a result, fighters are taking more punishment than necessary, especially, as noted above, when forced to the ropes.

Whenever their backs are to the ropes most of today’s fighters adopt Ali’s passive “rope-a-dope” posture. The “rope-a-dope” is both a dangerous and inadequate defense. It subjects the fighter to unnecessary punishment. In the entire history of boxing this non-strategy worked exactly once—when Muhammad Ali used it to exhaust George Foreman in 1974. His continued use of it in subsequent fights, and even in training, caused him untold damage. Yet Ali’s influence, good and bad, persists.

Mike Capriano, Jr.: “The old timers were exposed to many more fights, but at least they knew how to fight and protect themselves. They knew the ‘sweet science.’ Plus the trainers and all the people in the industry understood boxing better so they knew when a fighter was shot, knew when his legs were gone, and knew when he was hurt to take him out of the ring. They don’t know this today.”

One might think that by fighting only three or four times a year boxers are suffering less physical damage than the old timers. I’m not so sure. What I see are boxers getting hit with more punches in less than half the fights of their Golden Age counterparts. With all the sophisticated medical tests available and attention to pre and post fight physicals, the rate of injury and death in boxing has not decreased. It may be even worse today. Nevada, the second busiest boxing state after California, is supposed to have one of the finest boxing commissions. In 2005 two fighters died and two others sustained career-ending brain injuries. It was the first time since 1933 that two fighters died in Nevada in the same year.

Compounding the physical dangers of professional boxing are incompetent boxing officials. A serious problem that is not being adequately addressed is the competence of referees. There is far too much inconsistency in this area. Too many fights are allowed to continue beyond the point when they should have been stopped. State boxing commissions are part of the problem. They remain a convenient dumping ground for political hacks and cronies who are owed patronage appointments. The state boxing commissions could also take a much more active role in policing the sport if they stopped being subservient to the promoters and sanctioning organizations. There can be no middle ground when it comes to boxing safety. The main concern must be the physical well being of the boxer.

Ted Lidsky: “There’s always been a certain level of brain injury in boxing. In the older literature they talk about it. The averages go from 17 percent to about 25 percent of boxers walk out with frank dementia and about another 25 percent with clear cognitive problems like memory loss and all the rest. That’s 50 percent, and that’s a huge number. It’s really inexcusable. And that’s the way it used to be when fighters knew how to duck. Nowadays you see fighters who are still boxing, still relatively young, who are already slurring and showing all kinds of evidence of brain injury because they don’t get out of the way of punches at all. Whereas it was shameful before, it is totally inexcusable now. It’s wholesale brain injury. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

If, as renowned author and boxing maven Norman Mailer once said, “boxing is a dialogue with fists,” then today’s top fighters are conversing with a very limited vocabulary. Fighters used to take pride in their ability to avoid punishment. Today many of them take pride in their ability to absorb punishment. With defensive techniques at an all time low, many bouts appear to be nothing more than survival of the fittest contests.

In 2002 Mickey Ward (right) and Arturo Gatti fought like two late model cars in an endless demolition derby, turning their fight into a monotonous display of mindless brutality (AP/Wide World Photos).

It would be delusional to believe that boxing is not a brutal sport. But like a controversial work of art that some consider a masterpiece and others pornography, an especially brutal boxing match should at least have a redeeming quality to it. First of all, there must be an element of drama. At the very least, it should be interesting and entertaining, if not hair raising. Dempsey vs. Firpo, Zale vs. Graziano I and II, Basilio vs. DeMarco I and II, Moore vs. Durelle I, Arguello vs. Pryor I, Ali vs. Frazier I, Hearns vs. Hagler and Foreman vs. Lyle were interesting, entertaining and hair raising. In his description of the first Alexis Arguello–Aaron Pryor contest, boxing historian Mike Casey defined the quintessence of the genre as “a chess game that combined skill, nerve and an oddly poetic form of brutality.”3

I love a good rock ’em, sock ’em donnybrook as much as any fan. Few athletic events equal the electricity and excitement generated by a great pier six brawl between two evenly matched fighters. I know I am in the minority, but I cannot put the Mickey Ward vs. Arturo Gatti trilogy (2002–2003) in this category.

Junior welterweights Arturo Gatti and Mickey Ward were on the downslide when they crossed gloves the first time. Neither fighter had any pretenses toward greatness. Both were lion-hearted club fighters in the twilight of their careers out to prove who the toughest guy on the block was.

Ward vs. Gatti (specifically their first and third fights) was boxing stripped to its essence; two men attempting to beat each other into submission with their glove-encased fists. While I admired their heart and tenacity, I was disappointed by the almost total lack of boxing technique. There was not the slightest attempt by either fighter to avoid punches. The jab, boxing’s most effective and basic punch, was an after-thought. Footwork? The fighters knew only one direction—forward. Defense was non-existent.

The first Gatti vs. Ward fight (named in every poll as boxing’s fight of the year for 2002) was a vicious war of attrition. Every hard fought round was just like the one that preceded it. The fighters reminded me of two late model cars in a demolition derby that keep smashing into each other over and over—a fender would fall off, a rim sent flying, a grill smashed. But despite the hundreds of punches that found their target, neither fighter possessed enough punching power to put an end to their mutual misery. So the fight dragged on, round after round, with no let up or change of pace. It eventually became—to this observer—a monotonous display of mindless brutality. By the fourth or fifth round I found it unwatchable. There was a stupid quality to the violence. Gatti and Ward were fighting like two crazed masochists entertaining an audience of screaming sadists. This wasn’t what boxing was meant to be.

Crusading journalist Jack Newfield called boxing his “guilty pleasure.” It is a sentiment shared by many sensitive aficionados of the sport. I confess that I have enjoyed many a brutal fight, but Gatti vs. Ward drained the spirit of this guilt ridden boxing fan.

In their second fight, the more versatile Gatti, under the direction of his new trainer Buddy McGirt, wisely elected to box and move. He won an easy decision over Ward. I thought his change in tactics created a more interesting and entertaining contest than their first fight. But, for whatever reason, Gatti reverted to macho mode in the rubber match and the result was another crude and witless slugfest.

One journalist described their third fight as “breathtaking in its brutality”4. He is probably too young to have attended the Monday night fights at the old St. Nick’s arena in New York City. Every now and then a mini Gatti vs. Ward fight would take place on the undercard between two tough but limited preliminary fighters. Of course, by the time a fighter hit main bout status, he seldom fought with such reckless abandon. To do so, especially on a monthly basis, would be a prelude to career suicide.

Teddy Atlas: “Part of what made the first Gatti vs. Ward fight such a brutal fight—as much as we acknowledge their strengths—a lot of it was because of their lacking. Because a lot of those older guys wouldn’t have been quite as easy to hit with that many clean punches. In the eras we are talking about, those guys wouldn’t have found each other so easily.

“But that ninth was quite a round. They were magnificent in the way they acted as fighters. The sad part is that the people of today see so little of that kind of behavior … they don’t understand that was just automatic with almost all the fighters back in the generations we’re talking about. We appreciated it but we didn’t get up and set off fireworks when we saw a fight like that.”

In spite of the prevalence of fighters adhering to the “I hit you—now you hit me—now I hit you” school of artless boxing, there are a few contenders and champions who do attempt to hit and not get hit in return. But their actions are often misunderstood. When Roy Jones, Jr., zipped about the ring like a Mexican jumping bean on speed, the faux experts called him a “master boxer.” Of course, this was said before his three consecutive losses to mediocre opponents exposed Roy as a fighter possessed of tremendous speed and athleticism but with a minimum of solid fundamental boxing skills.

Erik Arnold: “Instead of really knowing how to box, guys like Roy Jones, Jr., Pernell Whitaker and Meldrick Taylor and the rest fly around the ring and they consider this brilliant boxing. I mean these guys don’t really know how to use a jab, they don’t know how to slip punches, they don’t know how to take advantage of opportunities. As Hank Kaplan would say, ‘They are speed merchants’ who don’t show any real boxing skills.

“Not long ago, on the undercard of a Wladimir Klitchko fight televised by HBO, I watched an American featherweight beat some talentless Mexican fighter. The American won easily just by flying around the ring and throwing more punches than the other guy. But according to Lampley, Foreman and Merchant [announcers for HBO], he was ‘showing consummate boxing skills.’”

Bill Goodman: “Boxing bears very little resemblance to what it was in the past. Even the lingo is different now. I don’t even know what the hell they’re talking about. The announcers use expressions I never heard before. ‘He’s throwing punches in bunches,’ they say. What the hell kind of shit is that? ‘He’s exhibiting a high work rate’ is another favorite. In all the years I never heard these expressions. The whole conversation and vocabulary is strange to me. The people running the show today don’t know the score. They don’t have the experience and they have no connection whatsoever with the past.”

A few years back the ephemeral heavyweight contender Chris Byrd exhibited a few evasive moves and was instantly labeled a “throwback” to scientific boxers of the past. The way some people talked about this very mediocre boxer you’d think he was the second coming of Gene Tunney. But after struggling to a draw with the crude Andre Golota, winning a squeaker over ordinary Jameel McCline and being destroyed by Wladimir Klitschko in 2006 even the clueless faux experts have stopped calling Byrd a “scientific” boxer.

In 1960 Dr. Max Novich, a former collegiate boxing champion and president of the Association of Ringside Physicians, gave the following description of scientific fighters of the Golden Age:

“These champions moved in the ring with agility by means of footwork always remaining balanced and in position to attack or defend. They never remained more than momentarily in one position. This made them moving and elusive targets. They shuffled, circled, advanced, side stepped or retreated to make an opponent miss or lessen the effects of a counterblow. They also developed a conditioned neuromuscular coordination of the hands and feet.

“This style of boxing is known as on-balance counterpunching. It is the jewel of boxing performance encompassing the mastery of all the techniques and skills of boxing such as blocking, parrying, slipping, bobbing and weaving, feinting, sidestepping, timing, judgment and poise. This is the boxing of championship caliber.”5

There is an expression that accurately captures in words the current state of the art. It is fight announcer Michael Buffer’s ridiculously stretched out catch phrase, “Let’s get ready to rummmmmble.” Without realizing it, this preening, well coiffed mannequin has given us the perfect clarion call for what boxing has morphed into: a mindless, destructive human demolition derby.

I am not trying to hide the fact that boxing is indeed a “rumble” of a sort. Professional boxing will always be a brutal and dangerous contact sport. But a true definition must make the distinction between boxing and a street fight with gloves. A six-year-old banging the keys of a piano produces sound—but not music. And two talentless but brave fighters clubbing each other senseless will produce a fight—but not boxing.

What a pity more people do not understand the difference.