Every day, I learn something. Duran is a better fighter than me, but he, too, is not great in the way that Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis, Kid Chocolate, Willie Pep and Henry Armstrong were great. The fighters in the old days were really great. If Duran and I were born in their time, it would’ve been impossible to go to the top. The old-timers fought like tigers.1

Alexis Arguello, former featherweight, super featherweight, and lightweight champion.

In 1984 American boxers won nine of 11 gold medals at the Los Angeles summer Olympic Games. No other Olympic boxing team had ever dominated the competition so completely. But there is an asterisk attached to this unprecedented achievement; Cuba and the Soviet Union, perennial Olympic powerhouses, did not compete in the 1984 Olympics. The communist boycott was payback for the United States’ refusal to participate in the 1980 Moscow Olympics after Russia invaded Afghanistan earlier that year.

With their toughest competition absent, the talented American squad easily dominated the rest of the field. However, when the Cuban and Soviet teams returned to subsequent Olympic competition, the results were quite different. In five Olympic tournaments since 1984 American boxers won only a total of seven gold medals compared to 35 won by boxers from Cuba, Russia and the former Soviet bloc countries. To paraphrase Professor Einstein: “Dominance is all relative.”

Many of today’s boxing pundits completely ignore “relativity” and historical perspective when they point to the dominance of Roy Jones, Jr., and Bernard Hopkins as proof of their greatness.

Before he turned pro in 1989, Roy Jones, Jr., was the best amateur middleweight boxer in the world. He was blessed with dazzling speed, trip hammer reflexes and above average punching power. Roy breezed through his early pro fights. Opponents simply could not match his extraordinary athletic gifts. Stymied by his speed and awed by his reputation, they were incapable of effectively countering his frenetic and unorthodox style of boxing.

[This photo appears in the print book

but is not included here

due to copyright issues.]

Roy Jones, Jr. (left) pulls away from Antonio Tarver’s jab in 2004. As Roy’s extraordinary speed and reflexes began to slow with age, his technical deficiencies were exposed—along with his suspect chin (Getty Images/Doug Benc).

As Roy continued his romp through the middleweight and light heavyweight divisions, his talent mesmerized both fans and faux experts. Many believed they were witnessing true greatness. The one blot on his record—a loss by disqualification—was avenged with a first round knockout. In a 14-year span (1989 to 2003) Roy won 48 of 49 fights while acquiring title belts in four separate weight divisions (middleweight, super middleweight, light heavyweight and heavyweight).

Roy’s army of admirers considered his victory over John Ruiz, in 2003, for a portion of the heavyweight championship, the crowning achievement of his career because he gave away height, reach and 33 pounds. Roy justified the 3-to-1 odds in his favor by pounding out an easy 12 round decision over his painfully slow opponent.

The fact that Ruiz was one of the worst fighters ever to claim ownership of the heavyweight championship should have tempered people’s enthusiasm. But the media, blind to reality and infatuated with Jones’ supremacy of the light heavyweight division, went over the top in praising his one-sided victory over a much heavier opponent. The most goggle-eyed tribute was this gem that appeared in the New York Times two days after the fight: “Just deal with the overall ring mastery, work ethic, technical proficiency and confidence: Jones and Ali are equal. There is a possibility that Jones pound for pound, may be even better. This is blasphemy, I know, but not too far to the right or left of the truth.”2

Other media comments were similarly off kilter. Boxing Digest magazine, said in its May-June issue for 2003, “Jones … made a case for himself as the best of all time with his easy domination of the hapless Ruiz.”3 The New York Post said on March 2, 2003, “Jones … won a masterpiece 12 round unanimous decision at the Thomas and Mack Center Saturday night.”4 To the faux experts, whose frame of reference and lack of perspective allows for such misjudgments, Jones’s one-sided victory over the incompetent Ruiz confirmed their opinion that he ranked with the greatest fighters of all time.

But not everyone was so quick to place Roy Jones, Jr., alongside boxing’s immortals. A minority of critics—mostly old school trainers—believed his athleticism was obscuring fundamental flaws. He was off balance much of the time and his defense was based entirely on speed, reflex and a sense of anticipation. His critics, and even some of his fans, were also put off by a reluctant warrior attitude. Consistent with Roy’s evasive hit and run style was his insistence that HBO-TV add a clause to his contract giving him the right to choose opponents.

Boxing is a dangerous sport and one can’t blame a fighter for attempting to earn as much money as possible while facing the least risk. But at the same time Roy sought out the weakest of the herd by choosing an assortment of docile challengers, he kept insisting that he was an all-time great fighter.

Before his shocking knockout losses to Antonio Tarver and Glen Johnson tarnished his stellar image, Roy Jones, Jr., was, in this writer’s opinion, the most overrated champion in the history of the sport. This is not to say he wasn’t a very good fighter. His speed, power and instinct made him an elusive and dangerous foe. At his peak Roy was a very good fighter—but he was never a great fighter as judged by the standards of the Golden Age.

Roy fought and trained in an environment that did not allow for much progress beyond his high-level amateur skills. It was only when his reflexes and speed began to slow with age that his technical inadequacies—and suspect chin—were exposed. When that happened he became just another fighter, and a very vulnerable one at that.

Jones never attained the high level boxing skills of a Tommy Loughran, Maxie Rosenbloom, Ezzard Charles, Archie Moore, Harold Johnson or Joey Maxim. These former light heavyweight champions were able to stay competitive even after they had gotten older and slowed down because they had acquired abilities and experience that supplemented their natural talent. Each had earned the equivalent of a Ph.D. in the art and science of boxing. Even in their dotage, when they were washed up, these fighters could still exhibit the classic moves of an experienced old pro.

Throughout the course of his 17-year career, Roy was exposed to a steady diet of second and third rate opponents. The weak competition provided little incentive or pressure to improve his boxing technique. He became complacent. Unlike the fighters mentioned above, Roy never became a savvy old pro—he just became old. When his speed and reflexes slowed there was nothing savvy to fall back on.

In an earlier era Roy would have been vulnerable even during his prime, before his speed and reflexes deserted him. The Golden Age pros, unlike their modern day counterparts, would have known how to override his athleticism, exploit his technical weaknesses, and find his chin. Roy’s one-sided victories over a slew of inept challengers fooled fans and faux experts alike into thinking he was an all-time great fighter. A few misguided souls even placed him alongside Sugar Ray Robinson. During his prime Roy’s toughest opponents were James Tony and Bernard Hopkins, who are, by Golden Age standards, just slightly better than average. He defeated both by decision, but there was no evidence of “greatness” in either fight.

In his iconic 1958 boxing novel The Professional, W.C. Hienz has an old school trainer named “Doc” Carroll explaining to a reporter why a popular undefeated champion is not all he seems. The dialogue could just as well be referring to Roy Jones, Jr.:

DOC: “People have the idea the other guy’s a great fighter. That’s a Joke.”

REPORTER: “He’s a pretty good one, Doc. Let’s give him that.”

DOC: “Sure he is. He’s champion of the world, isn’t he?”

REPORTER: “That’s what I mean.”

DOC: “But not a great fighter. Let’s not get confused about that. Quicker than the rest, so he covers better. He looks good at it, but he’s not what he looks. You’ve got to see through all that.”

REPORTER: “I can see it, now that you say it…. I could see that lithe brown body and the fast hands and all the natural grace, but I could see now that always, without it being a conscious thought, there had been the impression lying dormant within me that something was not there. It is the way a passage of music will raise you and then leave you up there all alone, feeling but not quite knowing that something is missing and wondering what is wrong.”

DOC: “Window dressing.”5

W.C. Heinz based the character of “Doc Carroll” on Jack Hurley, a master trainer famous for developing the great 1930s lightweight contender Billy Petrolle (known to fight fans as “The Fargo Express”). The authentic boxing experts interviewed for this book also possess the rare ability to see beyond mere “window dressing.” Therefore it comes as no surprise to this writer that the following comments were expressed while Jones was still undefeated and riding the crest of his supposed invincibility.

Teddy Atlas: “Roy uses his reflexes and his anticipation rather than technique. His technique has a lot of holes in it. I don’t think any real boxing guy would argue with that. I don’t even think Roy would. There are a lot of technically better fighters, but he depends on reflexes, a sense of anticipation, timing, those kind of great talents.

“But the old school contenders would have taken advantage of that. They would have set him up for punches. They would have been like those pheasant hunters that know how to decoy a pheasant that’s hiding in the bush to flush him out and into a shot—instead of missing the shot. They would have flushed him into it. I mean these guys would have taken advantage of his technical flaws and they would have put him into position to expose them. And then, once those technical flaws were exposed, I don’t think his speed and talent would be flaunted so much. I don’t think it would be up there for us to bow to anymore. Instead we would have said, ‘Well he certainly moved back quickly before he got caught with that left hook that put him on his ass,’ or ‘Wow, that looked like a real fast punch he just threw until he got hit with that body shot right after it.’

“The old timers would have had answers to his moves and instead of being awed—and that’s probably the right word—instead of being awed by his speed and power, we probably would have been looking more at his flaws. We wouldn’t have been saying, ‘Wow, look how fast he is.’ We would have been saying, ‘Wow, look at the way he pulled back and got caught with that left hook, look at the way he drops his hand for that uppercut, and look at the way Archie Moore saw the opening and dropped a left hook on his chin. Gee, too bad he wasn’t taught better. You know what? That fella Roy Jones, Jr., could have been a good fighter. He had a lot of ability.’

“I think Roy Jones, Jr., is a terrific athlete. He has a terrific combination of speed and power. But you know what? I don’t think he gets past Archie Moore. I’m sorry. And he doesn’t get past Harold Johnson, Ezzard Charles or Billy Conn either. I don’t want to keep going, but I could go on … I could. And I’m saying this for a reason. I could name ten old timers within four minutes of thought that he doesn’t get past. I mean these guys, especially in that division, were freakin’ monsters!

“All of the things we are talking about; the experience, the toughness, the endurance—and I don’t mean physical endurance—of having fought that kind of competition their whole life! Jones would have looked at his manager and said, ‘What are you doing? Where’s HBO? Where’s that contract? Wait a minute … let me read the contract.’

“Look. I don’t want to get too crazy. But when people talk about speed, I say what about the things the old timers had that took away speed, like body punching, feinting, cutting the ring down or missing a punch on purpose so you could make a guy like Jones, who made a lot of mistakes and pulled back from punches, move right back into a punch he never saw and say, ‘Where’d that punch come from?’ Or he might not even get a chance to say it.

“Fighting those killers that used to inhabit the light heavyweight division, your concentration had to be so keen every second or you were gone. Well, you know what? Jones never had to be in that kind of fight. So I’m sorry. But look. I think Roy is a terrific athlete and, as I’ve said, he has a terrific combination of speed and power. But you know what? All those guys had good combinations of speed and power.

“Why do I always have to protect the reputation of the old timers? Why do I have to be a guy that says it? Can’t somebody go to a library and appreciate these guys and look at the films that are there and appreciate what abilities these guys had instead of trying to see what they didn’t have? See what they had! The top fighters of today don’t have a market on these things. They didn’t invent anything new.

“The boxers who fought 50–60–70 years ago had to perform under far more difficult conditions, and they had to do it with tremendous fighters—all the time. I don’t know if Jones could have got through these guys. But let him get past one, then the next one, then the next one. I know he isn’t going that far. And I’ll take it one step further. I like Roy Jones, but I don’t know if he would have stayed in the business, because I don’t know if his temperament—forget about his abilities in the other areas—I don’t know if his temperament would have allowed him, on a consistent basis, to deal with that type of competition. People don’t understand that temperament is an ability.

“The temperament of the old time fighters would have outweighed a lot of other abilities that Jones had that they could match in physical terms too. I love guys like Archie Moore, Ezzard Charles, Billy Conn, but you don’t have to go to that stratosphere to identify fighters from that era who were capable of doing things that would negate what Jones does in the ring. There were so many others who would be able to overcome his speed and athleticism and expose Jones in the areas that he’s flawed.

“I do give Roy credit for doing so many things wrong and still being successful. He gets away with it. But instead of just looking at what Roy does well, I look at what he does wrong and why he gets away with it. That tells me a lot. He gets away with it not because of what’s there. He gets away with it because of what is not there. A good fighter would exploit those things.”

Dan Cuoco: “When Roy Jones, Jr., was in with a fighter he respected, or a fighter that could punch, he fought a defensive fight. Roy was not at his best when fighting defensively. The old timers would walk him down and work him over. I don’t think he could hold his own with forgotten greats such as Eddie Booker, Holman Williams and the Cocoa Kid, never mind a Ray Robinson or an Archie Moore. I think it would be no contest. I think he would even be respectful of a Carlos Monzon. Carlos would work him into the ropes—Roy never liked to fight on the ropes—and Monzon would have a field day with him.

“In his time Roy’s speed allowed him to get away with unorthodox methods. One of those unorthodox moves was to lead with a left hook. But a top fighter would not fall for that ploy. The fighters I mentioned would have used that left hook against him, countered it, and put him away. I’m picking the old time greats over Roy Jones, Jr., who I think was a little more flash than substance.”

Freddie Roach: “I don’t mean to rap Roy Jones. But I don’t see him as a great fighter. He’s a talented athlete. He’s probably a great athlete because he can play a lot of sports and his natural ability of speed, which is a great asset of course, especially in the sports world, is tough to conquer. But if Roy Jones doesn’t knock you out early he usually doesn’t knock you out late.

“It’s the punch you don’t see coming that usually knocks you out and Roy has that great blinding speed, but once he slows down a little bit in the later rounds he becomes less effective. And now that he’s getting a little bit older I think he’s going to get exposed a lot more. Back in the old days there were good fighters. They learned their sport. A lot of the champions nowadays are just good athletes and they can get by because there’s not a lot of competition like in the earlier days.

“I think one of the best throwback fighters that I’ve had a chance to work with was Marlon Starling, who was welterweight champion in the 1980s. He was really a throwback. He learned his trade. He learned the art of boxing. He wasn’t just naturally gifted. He had to work at his game.

“Roy Jones, Jr., is a tremendously gifted athlete but he is technically flawed. He crosses his legs. He walks with his left foot first when he goes to his right, when he makes that cross. If I see a fighter doing that I know I’m going to attack right away because once those legs are crossed like that I’m going to put him right on his ass. He walks heel to toe a little bit. He doesn’t stay on his toes like a fundamental fighter should. He gets away with it because he has such blinding speed. But with him getting a little bit older speed is something he is going to lose, and when those speedy guys lose that split second it’s only a fraction of a difference but it takes a toll on them. The speed was enough to get them by. Back in the old days you needed a lot more than speed to get by.

“I think Archie Moore and Bob Foster are beating Roy Jones, and even Michael Spinks, who came a little bit after them and was a pretty good fighter. When Spinks came along the light heavy division was pretty good at the time. You had Dwight Qawi, Eddie Mustafa, Matt Franklin. It was competitive but none of them were great fighters technically. They were just more or less tough guys.

“I think the art of boxing has changed over the years. I had 54 pro fights, the last one in 1987. Now 54 fights is not a lot of fights compared to the guys back then. Years ago guys fought two or three hundred pro fights and they really learned their craft. Experience is a great asset. We get better with age, we learn. The thing is, I don’t think that fighters of today get that capacity to learn.”

Rollie Hackmer: “Roy Jones, Jr., is off balance much of the time and his feet are too wide apart. He has fallen on the canvas several times. Those are amateurish instincts. A good fighter doesn’t get caught up in a situation like that and he does that too frequently. Roy does not rank as a great light heavyweight. My fighter, Doug Jones, would have knocked him out. Lloyd Marshall would have knocked him out. What do you think Ezzard Charles would have done with him? Handed him his head!”

Wilbert “Skeeter” McClure: “It takes a great opponent to make you a great fighter and Roy Jones, Jr., hasn’t fought one yet. That’s OK. That’s history. Some presidents never have big wars in which they can win and become heroes. That’s the way the ball bounces. Jones hasn’t fought an opponent that even came close to bringing out the best in him. I said the same thing about Mike Tyson before he fought in Japan against Buster Douglas.

“I was in Atlantic City for the Tyson vs. Michael Spinks fight and some sports writers were praising Mike Tyson, saying he’s the greatest heavyweight ever and I said to them, ‘Don’t you guys have memories?’ Mike Tyson hasn’t fought a fighter yet who wanted to beat him, who would say, ‘I would die before I would let this man beat me.’ He never fought an opponent like that. All the great heavyweights have fought guys like that. Until Tyson fights a heavyweight who says, ‘I want to beat you and there is no way in the world I will not beat you’—when he gets knocked down, when he gets a cut eye, when he gets a bloody nose in the third or fourth round and he struggles, his greatness remains a question mark.’

“Buster Douglas started Tyson’s downward spiral. Cus D’Amato once told me, ‘Every time one of my fighters walks in the ring he has an 80 percent chance of winning. I don’t gamble. If you were my fighter every time you would have walked into the ring you’d have an 80 percent chance of winning.’ And that’s the same pattern he followed with Mike Tyson. He knocked out nearly everyone he fought. In one year he had three 90 second KO’s. That was supposed to happen. But that did not prepare him when he fights a Buster Douglas, or he fights a Holyfield, or a Lennox Lewis, and he’s hurt and its not in his system that ‘I’ve got to fight, fight, fight.’ That’s what I am referring to.”

Mike Capriano, Jr.: “Roy is not in the same area of quality as some of the people we’ve spoken about, certainly not the quality of an Archie Moore, Lloyd Marshall, Jimmy Bivins or Gus Lesnevich. My goodness! Jones as one of the greatest light heavyweights of all time? Let him box Floyd Patterson at 170 pounds. Patterson would beat him both as an amateur and as a pro. Victor Galindez and John Conteh would have beaten him. Archie Moore would have banged him around. In a fight between Roy Jones, Jr., and Saad Muhammad, I’m betting Saad.

“To be great you have to go through the killers—provided you survived and were not damaged too badly. Look at Moore’s opponents. I mean this is ridiculous! There is no way you can rate the fighters of today with the fighters of that era. I don’t care what they do or how many title defenses they put up.

“You can’t blame Roy Jones for not having the competition for proving himself when he was at his peak. There were no Lloyd Marshalls or Carlos Monzons around to test him. I’m not blaming the fighters. I’m blaming the guys that rate them. I wouldn’t characterize the fighters as being at fault for being overrated. It’s the people that come up with these ‘all-time rankings’ who are at fault. The guys that rate the all-time great fighters don’t have the understanding, they don’t have the exposure. It’s their problem, but their ratings are not to be accepted because they’re wrong, they’re fallacious. There is no doubt about it. Absolutely no doubt about it. They haven’t seen the great fighters and they don’t know what to see when they do see the great fighters [on film].

“It’s similar to the trainers who don’t know what to tell their fighter because they haven’t experienced that situation. They haven’t been up all those stairs, right to the top, and recognized the learning methods that the great fighters were fortunate to have. You just can’t give these current guys that kind of rating, absolutely not. It’s ridiculous. Just a few years ago they were making Shane Mosley another Robinson. Then he fought Forrest and is beaten twice. There are no Robinsons, no Armstrongs, no LaMottas.”

While there are no fighters today who are comparable to a Sugar Ray Robinson, Henry Armstrong or Jake LaMotta—it is also evident there are no fighters who compare to their toughest competition either.

You will not see the likes of Bernard Docusen, a brilliant boxer who gave Sugar Ray Robinson one of his most difficult fights at welterweight. Nor will you see fighters resembling middleweights like Georgie Abrams or Jose Basora, two master craftsmen who never won a title yet extended Robinson in hard fought decisions when the Sugar Man was still in his prime.

During the 1930s “Hammerin” Henry Armstrong won titles in three separate weight classes (featherweight, lightweight and welterweight) in one ten month span. Armstrong is universally ranked among the greatest of the great. Yet a forgotten iron man named Baby Arizmendi went to the post with Armstrong on five different occasions and not only did the tough little Mexican last the distance every time, he whipped Armstrong in their first two fights. Davey Abad and Willie Joyce, two outstanding boxers, also gave a prime Armstrong all he could handle in multiple fights.

Holman Williams campaigned in both the welterweight and middleweight divisions in the 1930s and 1940s. Legendary trainer Eddie Futch called Williams the greatest pure boxer he ever worked with.

Can you imagine any of today’s world champions extending a prime Sugar Ray Robinson or Henry Armstrong? Can you imagine any of today’s top middleweights extending Jake LaMotta?

In 1993 I asked Mike Capriano, Sr., the trainer who discovered, taught and managed Jake LaMotta, to name The Bronx Bull’s toughest opponents. He named Sugar Ray Robinson, Jose Basora, Jimmy Reeves, Tommy Bell, Lloyd Marshall, Fritzie Zivic, Bert Lytell, Marcus Lockman and Holman Williams.

Aside from Robinson, the best of the lot may have been Detroit’s Holman Williams, a stable mate of Joe Louis. How good was Williams? The legendary Eddie Futch, who trained hundreds of fighters and 17 world champions from the 1930s to the 1990s, said Holman Williams was “the greatest pure boxer I ever worked with.”6

During the Golden Age of talent and activity, the middleweight division was considered the toughest of all the weight classes. A 160-pound fighter was light enough to move with extreme speed, yet heavy enough to punch with significant power. Some middleweights were capable of dropping heavyweights. But no matter how great the fighter, the depth of talent and competition made it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for any active middleweight to remain champion for more than three years.

The deterioration of boxing’s infrastructure during the 1950s resulted in a gradual decline in both the quantity and quality of boxers. Every weight division was eventually affected. By the early 1960s only a handful of Golden Age middleweights was still active. They included Joey Giardello, Gene Fullmer, Dick Tiger, Henry Hank and George Benton. Other top middleweights of the period were Emile Griffith, Joey Archer, Luis Rodriguez and Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. Such stiff competition precluded any one fighter from establishing dominance over the division. This was the last decade the middleweight division was capable of fielding a similar grouping of world-class fighters.

It was not until the 1970s that a middleweight was able to establish dominance and hold onto the title for more than three years. That fighter was Carlos Monzon, an arguably great fighter, who won the title from Nino Benvenuti in 1970. Monzon held the title for seven years and defended it a record (up to then) 14 times. No other middleweight champion had ever come close to those numbers.

Carlos Monzon retired in 1977, at the age of 34. Three years later, in 1980, Marvin Hagler won the championship. Hagler also dominated the middleweights for seven years, defending the title 11 times. He retired in 1987, at the age of 32, after being outpointed by Sugar Ray Leonard.

It is no mere coincidence that two boxers, less than a decade apart, dominated the middleweights for seven years. The key to their longevity—aside from their obvious talent—was the middleweight division’s almost total lack of top tier challengers. Once Monzon and Hagler had dispensed with the two or three fighters who posed the greatest threat, they ran out of serious competition. This had never happened before.

After defeating Benny Briscoe and an aging Emile Griffith, Monzon’s toughest opponent was formidable Rodrigo Valdez. Monzon strengthened his claim to greatness by outpointing Valdez, a genuine throwback fighter, in two closely contested title fights. The rest of his defenses involved ordinary club fighters such as Jean Claude Bouttier, Tom Bogs, Tony Mundine, Fraser Scott and Tony Licata.

Marvin Hagler’s top challengers included Vito Antuefermo, Alan Minter, and Tommy Hearns, whose decision to slug it out with Hagler resulted in one of boxing’s most spectacular first rounds. His other challengers—“Caveman” Lee, Mustafa Hamsho, Tony Sibson, Wilford Scypion, Juan Roldan—were all tough but ordinary fighters.

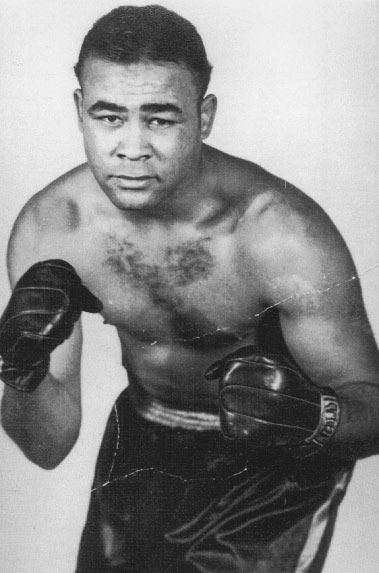

Archie Moore named Charley Burley (above) the greatest fighter he ever faced. But even the prodigiously talented Burley could not remain undefeated in the torrid middleweight division of the 1940s (The International Hall of Champions).

The quality of fighters turned back by Hagler and Monzon, in all but a few of their title defenses, pales in comparison to the many great and near great middleweights who populated the division four decades earlier. These fighters gave the division the fearsome reputation it justly deserved: Jake LaMotta, Charley Burley, Archie Moore, Jimmy Bivins, Lloyd Marshall, Holman Williams, Ezzard Charles, Jose Basora, Cocoa Kid, Marcel Cerdan, Bert Lytell, Tony Zale, Al Hostak, Eddie Booker, Freddie Steele, Fred Apostoli, Teddy Yarosz, Georgie Abrams, Ken Overlin, Alabama Kid, Nate Bolden, Billy Soose, Steve Belloise, Jack Chase, Allen Mathews, Solly Krieger, Ceferino Garcia, Kid Tunero, Coley Welch, Jock McAvoy and dozens of additional fringe contenders and first-rate journeymen boxers who were a test for any middleweight in the world.

Archie Moore fought ten of the fighters mentioned above. He often stated that Charley Burley was the greatest fighter he ever faced. Eddie Futch was in awe of Burley, calling him “the finest all around fighter I ever saw.”7 In 1991 Futch described the way Burley fought to author Ronald K. Fried: “He was really something to see. He was a master at slipping punches, counterpunching. He walked to you with a good jab, feint and make you miss. He didn’t move his legs too much, he’d just slide over, make you miss a punch and he was right there on top of you with either hand punching.”8

But even a fighter of Burley’s astonishing talent could not establish complete dominance in the torrid middleweight division of the 1930s and 1940s. During his prime Burley lost to Jimmy Bivins, Bert Lytell, Ezzard Charles, and Holman Williams, and boxed draws with Cocoa Kid and Georgie Abrams. One has to wonder how Marvin Hagler and Carlos Monzon would have fared against these outstanding middleweights?

Mike Capriano, Jr.: “Marvin Hagler would have been too good for the middleweights of today. Yet the people we knew in the 1940s and early 50s would outbox Marvin Hagler. From our experienced eye, the people that we saw looked better, were better, and had an understanding of what to do. And they were all better inside fighters. They knew how to drop four or five punches on the inside and tie the opponent up to prevent him from getting his own punches off.”

Emanuel Steward: “I think Ray Leonard, Tommy Hearns and Marvin Hagler would have been strong with any era. Marvin would have been a problem, regardless of what people think, for a Ray Robinson or a Carlos Monzon. He was a solid and fundamentally sound fighter.”

Tony Arnold: “If a fighter dominates his division he’s the best of his time. But if he’s dominating a piss poor division with third-rate fighters that, only means he was better than them. It does not mean he was great. Look at the type of opposition Jake LaMotta, Ike Williams, Sugar Ray Robinson and Kid Gavilan faced year after year. Hagler never fought anybody like that. He could have been a great fighter but he has yet to prove it to me.

“Hagler had defenses against the likes of Roldan, Obelmejias, Hamsho and Sibson. They were ordinary. Hagler was a good enough fighter to dominate ordinary opposition. Does that make him great? I don’t know. He had a lot of ability. But there was no excuse for his loss to Sugar Ray Leonard. No top-notch middleweight rated as great as Hagler would be able to lose to a Sugar Ray Leonard who was throwing flashy but very weak combinations. And he barely beat an over the hill Roberto Duran. Can you imagine Tony Zale having trouble with an over the hill Roberto Duran at middleweight? He would crush him in three or four rounds.

“Hagler could not beat Rocky Graziano. And believe me, Graziano was no great fighter. I think Rocky would have knocked Duran out as a middleweight. Duran couldn’t face a real middle. I’m not blaming Hagler. What I’m saying is I don’t think you can truly rate him as a great fighter because he never proved himself to me as a great fighter. He proved that he was a very good fighter against third-rate opposition. Does that make him a great fighter? I don’t know. In my opinion I say no. I’m not saying he wasn’t a great fighter. I know I’m contradicting myself. What I’m saying is he might have had greatness in him because he was a damn good fighter but whether or not he could have been great I don’t know. There’s no way to answer that because he never fought the type of fighters that would have proved to me that he was great.

“I think Monzon had greatness in him also. He showed real ability against certain fighters. Monzon showed against Benny Briscoe that he could really box. But neither fighter ever faced opponents of the caliber of Freddie Steele, Solly Krieger, Ken Overlin, Fred Apostoli and Teddy Yarosz. How good were those guys? Look at their records.”

Erik Arnold: “My dad and I were watching films of Sugar Ray Robinson’s 1950 European tour the other day and then took a look at some of Hagler’s fights. You could see that Hagler didn’t have that flow. A great fighter has a certain flow in his style that appears completely effortless. Hagler didn’t quite have that effortlessness. It was one punch followed by another punch in automatic sequence. He was mechanical and couldn’t deal with movement. This is one of the reasons Leonard defeated him, and it’s also why Duran gave him trouble.”

Dan Cuoco: “Marvin Hagler was another fighter who didn’t perform at his best when he gave certain fighters too much respect. That’s what happened when he fought Roberto Duran. It resulted in Duran going the distance with him and giving him a much tougher fight than it should have been. If Hagler fought somebody like Carlos Monzon I think the fact that he would have given Monzon that same respect would have taken Marvin’s best attributes away from him because he would have been a little too cautious and would not have let his punches flow the way they normally would flow. I think they both had great chins so I see the fight going the distance. I’m picking Monzon over Hagler by decision.”

Whether one considers Carlos Monzon and Marvin Hagler great, near great, or just very good, there is no arguing that both were highly evolved seasoned boxers; Monzon fought 81 times before he won the title. Hagler took the title in his 54th pro bout. Had they fought in the Golden Age, both would have been ranking contenders and perhaps even won the title, but they would never have been as dominant as they were in their own time. Until the early 1960s the middleweight division was just too damn tough.

By the time Bernard Hopkins became middleweight champion in 1995, the division’s talent base was even thinner than it had been during Monzon and Hagler’s era. Bernard Hopkins was 30 years old and a “veteran” of 29 professional fights when he won the title. Over the next ten years he defended his laurels a record breaking 20 times. Nine of his defenses came after his 35th birthday. Hopkins was 41 years old when he finally lost the title to Jermain Taylor in 2005.

The faux experts point to Hopkins’ unprecedented run of 20 straight title defenses as proof of his greatness. It is a number they can understand. What they fail to understand is boxing. Taken out of historical context, 20 title defenses is quite impressive—not unlike the record-breaking number of gold medals U.S. boxers won in the 1984 Olympic Games in the absence of their toughest competition.

When cold statistics replace balanced and informed analysis, all perspective is lost. Do the people assigning greatness to Hopkins consider that 18 of those 20 defenses were against fighters who would have been prohibitive underdogs if matched against the weakest challengers of Monzon and Hagler?

Great middleweight champions such as Sugar Ray Robinson, Mickey Walker, Freddie Steele, Harry Greb, Marcel Cerdan and Jake LaMotta could never have defended their titles 20 times over 10 years against the kind of brutal competition that populated the middleweight division from the 1920s to the 1950s. It is even more ridiculous to think any of these fighters—no matter how great—could have been “dominant” in their eras as they approached their 40th birthday.

Tony Arnold: “I never saw a sport deteriorate in every way that boxing has. The fact that Bernard Hopkins can remain champ for 10 years and make 20 successful defenses doesn’t show how good Hopkins is—it shows how bad the sport has become.

“Hopkins is an ordinary talent who is a little better than the talent that’s around him. He is a decent fighter for today. Fifty or sixty years ago he’d be considered an ordinary fighter. Maybe he would have been a main event club fighter in the small clubs.

“Ordinary fighters dominate today because their opponents are less than ordinary. That’s the key. These so called “experts” rate Hopkins among the top ten middleweights of all time, but how can they evaluate great fighters if they don’t recognize the quality of their opposition? All they know is Hopkins was champ for ten years and he had 20 successful defenses. That makes him great?

“They are using the wrong criteria for judging a fighter. Today’s boxers, after they turn pro, get a little bit better, and a little bit better, and then their ability reaches a certain level and it stays the same because they are fighting mostly third-rate club fighters for the rest of their careers. Even though some of today’s talent may well have developed into terrific fighters if they had fought during the Golden Age, they can never really improve because the quality of their competition does not improve.

“Years ago you fought progressively better opposition, so when a guy got to the top you knew he was beating better and better fighters. They had so many fights against so many good fighters that after a while they had the answer to everything. They fought fighters with every different style—but fighters with skills. Hopkins is fighting other club fighters his whole career. How is he ever going to develop?

“I saw Hopkins on the way up and I never thought he looked that good. In his first title fight against Segundo Mercado he was dropped twice. He made excuses about the height of his opponent but that was no excuse. The fact is that a very ordinary fighter held him to a draw. A great fighter, in any division, even if he’s off, doesn’t have trouble with someone like Mercado. Even if he doesn’t look good he still whips these guys. It was just a poor performance by a fighter who himself is just a glorified club fighter.

“You used to see fighters with certain skills. Where are middleweights like Joey Giambra, Willie Troy, Bobby Boyd, Spider Webb, Florentino Fernandez or Georgie Benton? You don’t see anyone on that level today. The top fighters of today, if matched against the really good fighters of years ago, would look like rank amateurs because the things they are able to get away with they would not get away with against the old timers. Could you see De La Hoya at 145 pounds with any of the good fighters of the past? I do not see him beating any of the major contenders. It’s not even close with a Luis Rodriguez or Emile Griffith in their primes … or Billy Graham … or Gil Turner. I also cannot see Shane Mosley, at his best, defeating championship caliber fighters from the 1930s, ’40s or ’50s.”

Teddy Atlas: “Hopkins does get a little too much credit in certain areas, but the things that I do like about him are that he has learned how to fight. He is a well-rounded boxer. I’ll give him credit for that. But there’s so much missing nowadays that he can get away with calling himself ‘old school’ because people don’t even know what ‘old school’ is.

“I like Bernard, and he probably is ‘old school’ for what’s around today. Except don’t go to the old school because—and it’s not a knock on him—what he doesn’t understand is that all those guys knew how to fight in those days. And the temperament that he brags about? Having a fighter’s temperament. Well guess what? The old school fighters didn’t brag about it because they all had that quality.

“Look, as I’ve said, for today Hopkins is a well-rounded fighter. He can fight inside and he can fight outside. He times guys. Hopkins was a much better fighter than Felix Trinidad, who was much more one-dimensional. Trinidad was made to order for Hopkins. But, having said what I said, he still doesn’t come up to all those other things. It’s more a matter of the game being so depleted of real fighters today that if a guy tells us he’s just like an old school fighter and he shows us a little something, we automatically close our eyes and say ‘yes.’

“But the reality is that he’s not beating a Holly Mims or a Joey Giardello, or a Gene Fullmer. He’s not beating any of the top middleweights from the 1940s and 1950s. When he would start to move around and do his stuff and they started hitting him in the body, and they started stepping to him and suddenly they were three inches out of range, and then they were six inches into range before he even knew it and he wouldn’t know how to get rid of them. It would have been a different story.

“If Bernard were fighting back then he would have to find a way to create more offense. He would not have been allowed by those guys to win with only defense. That is what he is known for. Defense is his forte. That’s what separates him and he gets moved to the front of the class by being defensively responsible. But in those days that would not have been enough, because those guys would have been those things too but they would have been aggressive, and they would have forced him to find a way to either be more aggressive or lose.

“Bernard is put on a pedestal today for being smart and cautious. People say he is a good defensive fighter, which he is. In today’s landscape he can get away with being 90 percent defensive. In those days that wouldn’t have gotten him on a subway—not with these guys—because that would only have been part of the solution. He would have to have found a way to be more offensive minded to win fights with these guys—not just fence with them.

“Bernard is a good fighter, but in the era that we are talking of he doesn’t stand out. He becomes just another one of those guys that can’t get it on that level.”

Erik Arnold: “After Bernard Hopkins knocked out Felix Trinidad, Larry Merchant said that Hopkins “is one of the best middleweights of all times.” Merchant actually said this. It’s on the tape. I say based on what? Hopkins didn’t show any real ability in that fight.”

Dan Cuoco: “I think Hopkins’ skills would have allowed him to compete in any era. I see him fighting competitively because Hopkins has, over the years, learned the tricks of the trade. He knows how to slip punches, he knows how to fight and conserve energy and he knows how to defend himself. I also think he’s a good counter puncher. But Hopkins’ style of fighting is probably more effective today than it would have been in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s. Bernard often leads with his head. The fighters of the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s learned how to angle their bodies to a point where opponents were not going to butt them as often as you see in today’s era.

“Today’s fighters seem to come in with their head before their gloves. I remember reading how the old timers trained day after day to properly position their bodies, learning how to lean forward so that if they were butted they always got hit on the side of the head and not directly head on. So I don’t think one of Hopkins’ most effective weapons—his head—would be as effective against the best fighters of previous decades. He is skilled enough to at least be competitive, but I don’t see him having an edge over them.”

“Bernard Hopkins was very effective when he fought guys that were flawed, such as a Felix Trinidad. He owned them. But we’re talking about guys that weren’t flawed, contenders and champions who continuously fought the best of their era. Hopkins, in his lifetime, may have gotten in the ring with only seven or eight guys who were skilled fighters.”

Bill Goodman: “Bernard Hopkins is a good fighter in today’s market. But compared to the better middleweights of the past he is not a great fighter.”

Are these experts being too hard on Bernard Hopkins? Let’s start with Bernard’s record. As of July 2007 he has had 54 fights in 18 years as a pro. That averages out to only three fights a year. Reviewing tapes of his fights reveals to the knowing eye that Hopkins is an intelligent yet unremarkable boxer possessing decent defensive skills, a professional attitude and a solid punch. While these qualities are more than enough to make him a dominant world champion today, fifty years ago such skills would have been considered commonplace.

The fact that a 38-year-old middleweight was still dominating what used to be considered boxing’s toughest weight class says far more about boxing’s decline than it does about Hopkins’ alleged greatness. His impressive victories over the talented but robotic Felix Trinidad and an overweight and under motivated Oscar De La Hoya are not, by themselves, proof of greatness.

Teddy Atlas: “People say Bernard’s got an attitude like the fighters of the old days. The only difference that I would say about that, to argue it or contest it a little bit, is that if he really had the attitude of those other guys he would have taken advantage of his position after he defeated Felix Trinidad and shown more eagerness to fight.

“It looked like Hopkins was really going to miss his opportunity after he beat Trinidad because he only had two fights against ordinary opponents over the next two years. The old time guys in that same position would have found a way to fight…. I don’t know how many fights … but they would have made sure their dance card was filled a lot more than he filled it.

“Maybe he was lucky, but things did work out his way because in the end he made money and he’s still making paydays. There’s no denying that. But he could have paid a price had the times not been fortunate for him. Years ago, with the abundance of fighters that were around in those days, his boat would have sailed without him. But there is such a shortage of marquee names nowadays that he was able to still get plugged into lucrative fights.

“Bernard was opportunistic. He was picking his spots—which I’m not knocking him for. I think he should be given as much credit for being a good manager as he is for being a slick fighter because he wound up making a lot of money. But Hopkins benefited from boxing’s barren landscape. There are so few guys that you can sell to the public nowadays. The public doesn’t have any faith or trust in knowing there is going to be just solid fights. Other than the few big marquee names they are skeptical about how many good fighters are out there, and rightfully so. But in the old days you could sell 20 guys in one division to fight the champion. If Carmen Basilio or Gene Fullmer all of a sudden said, ‘Hey, I just won the title, I ain’t fightin’ nobody,’ everybody would move on without them. There’d be 20 other guys to consider and they’d be left at the freakin’ curb. But nowadays it’s almost like the inmates are running the asylum. The fighter can say ‘Hey, freak you. Who are you going to sell?’ And in reality they’re right. There’s nobody to sell. So Hopkins benefited from boxing’s barren landscape more than he benefited from good judgment.

Again, I’m not knocking him, but he did not match the actions and attitudes of the old timers in terms of his eagerness to fight after defeating Trinidad. He can argue and say that during that period he was smart. And, luckily, it did turn out well for him. But if the boat had sailed because people had other choices, then how smart would it have been? So that bragging about his temperament rings a little hollow. Not that I’m perfect, but I’m looking at it with a little more earnest eye. I’m not just going along with what he’s telling me. I’m going along a little bit with what I’m actually seeing. And I’m going along a little bit with a comparison of what it could have been and what it was.”

Kevin Smith: “I think Bernard Hopkins can be thrown back into the 1950s, maybe even the 1920s, and he’d be semi-successful. He does a lot of things well, it seems. He is well schooled, by today’s standards. But today’s standards are far lower than they were in the 1920s or the 1950s. There were great fighters in every era. There are even great fighters today. Are they as great as the 1920s or 1950s? No.”

Rollie Hackmer: “Bernard Hopkins would be a good journeyman with some of these fighters from the past. He had average boxing skill. A fighter like Joey Giardello would have taken him apart. There were so many good fighters at that time. What do you think Tony Zale would do with these fighters today … what do you think he would do with Roy Jones, Jr.?”

Hank Kaplan: “Hopkins has a lot going for him. He’s got great determination and a lot of heart. At the beginning he was not that skilled a boxer, but as he matured and slowed because of age, he developed good defensive techniques. But a good boxer, like the early 1960s middleweight contender Joey Archer, may have been a little too busy for him with his skilled use of a left jab and great footwork. Henry Hank, another top middleweight of that era, had a persistent offensive attack that may have nullified Hopkins’ defensive skills.”

Mike Capriano, Jr.: “Bernard Hopkins and Roy Jones Jr. are good but not great fighters. Sam Baroudi, a contender from the late 1940s, would have beaten both of them. Fighters who were not even considered outstanding during that time would have beaten Bernard Hopkins. Middleweight contender Herbie Kronowitz, a good boxer, tough and experienced, with an excellent jab and footwork, would have beaten Hopkins. In his prime Ralph “Tiger” Jones would have beaten him as well.

“The best fighters of recent years would also not have fared as well against the old timers. Tommy “Hit Man” Hearns won five world titles. Jake LaMotta would stop him. Rocky Graziano would stop him also because Hearns couldn’t take a punch and Leonard and Hagler stopped him. Hearns would not have stood up to the killer welters, middles and certainly not the light heavyweights of the 1940s.

“Styles make fights. All of the dangerous old time contenders were “Hit Men,” and they could take a punch and were crafty. Hearns had guts but could not take these killers. The old super middleweights of the 1940s such as Lloyd Marshall, Bert Lytell, Jimmy Edgar, Eddie Booker, would have KO’d him. Hearns’s record is 61 wins out of 67 fights, with 48 KOs. The record is misleading. It’s a toss up between Hearns and De La Hoya, as to who would have won.

“There was a much better level of fighter in the old days. You can win seven titles today because of the alphabet soup organizations and all the added weight classes. Maybe the good fighters of today would have developed better had they fought in the old days, but the way they are now, it would not happen.”

Carlos Ortiz: “Bob Foster would knock out any light heavyweight today. They couldn’t compete with a Bob Foster. Are you kidding? Who could beat Archie Moore today? Nobody. Nobody! They don’t have the quality. Harold Johnson? Forget it. Those were good fighters. I would bet all my money on yesterday’s fighters against today’s fighters.”

In their primes Roy Jones, Jr., and Bernard Hopkins were talented fighters surrounded by a sea of mediocrity. They never reached the skill level or experience of Carlos Monzon or Marvin Hagler—the last arguably great middleweights of the 20th century—but they didn’t have to. Both Jones and Hopkins benefited from the worst assortment of challengers ever faced by a middleweight or light heavyweight champion since the advent of boxing gloves. Is it any wonder they stood out as giants in a land of pygmies?