It’s like putting sand in the gas tank of a Ferrarri.

Edward Villella, former amateur boxing champion and world-renowned ballet dancer, on the negative effect of weight training for boxers and dancers.

It may sound strange, but I believe the movies Rocky III and Rocky IV influenced the current weight training trend among boxers. The movies, produced in 1982 and 1985, came out about the same time new and innovative strength training techniques were being developed for athletes in track and field, wrestling, football, baseball and golf—but not for boxing.

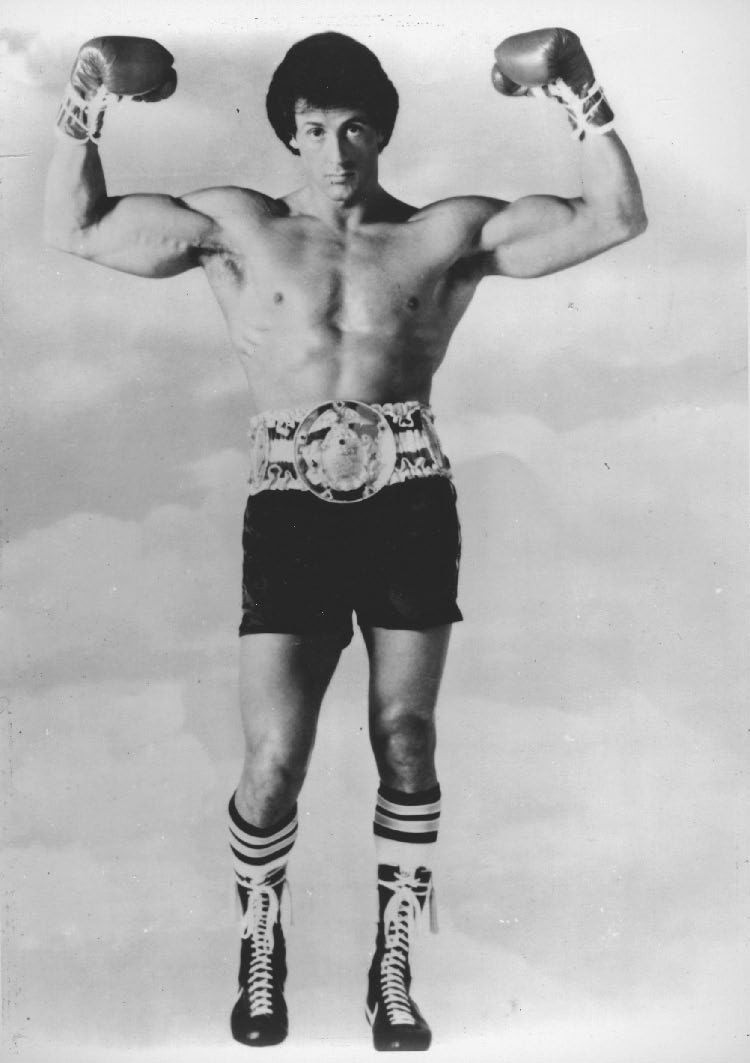

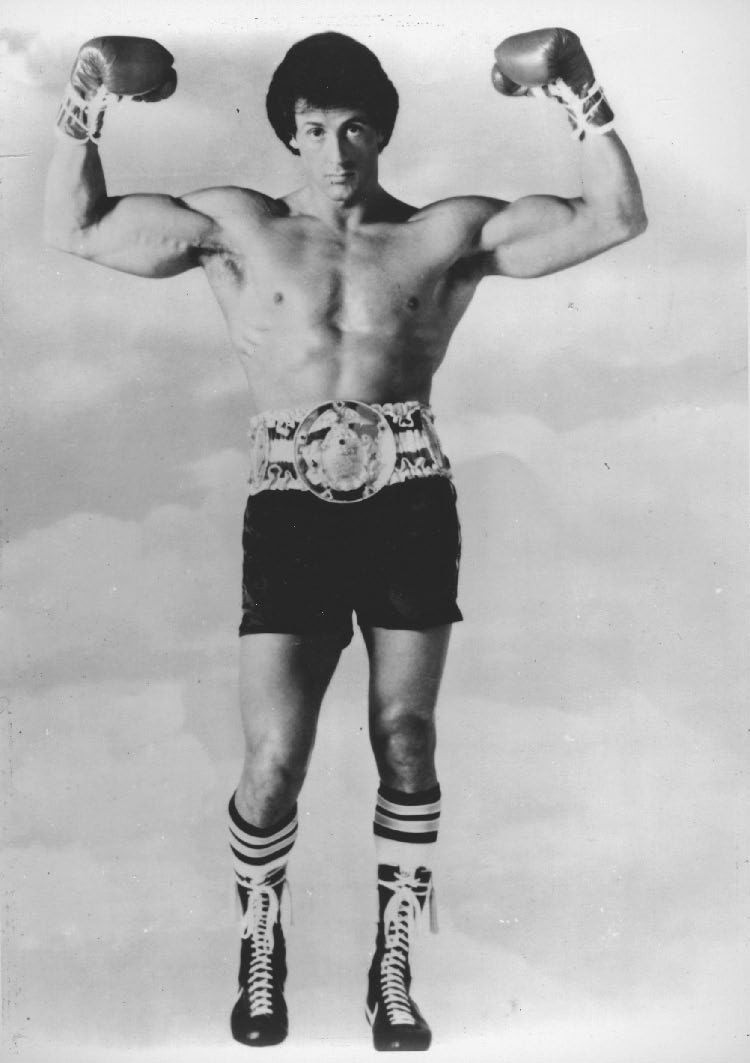

For Rocky III, Sylvester Stallone trained with world famous body builder Franco Columbu to fashion a physique that would have been the envy of any Mr. America contestant. Stallone had obviously spent months pumping some serious iron. He had the cut abdominals, wide lats, huge biceps and grapefruit sized deltoids of your classic muscle bound body builder. During the training scenes the movie showed him lifting heavy barbells, something that was missing from the first two Rocky movies. But Stallone’s impressively sculpted body was not a realistic depiction of what a fighter is supposed to look like. In the real world his physique would be totally unsuitable for boxing.

In Rocky IV the villain is played by the even more impressively built 6' 5" Dolph Lundgren. The movie depicts Lundgren’s character as an evil Russian heavyweight (Rocky IV was released a few years prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union) reaping the benefits of the latest “scientific” advances in physical conditioning. The training has turned him into a super fighter of immense strength and power. There are several scenes showing him cardio training and lifting weights while connected to a bunch of wires and monitoring equipment that looks straight out of Dr. Zharkov’s laboratory. He is also shown receiving injections of what are presumably steroids.

It wasn’t long after these highly popular films were released that many boxers began to appear with the oversized and out of proportion muscularity indicative of someone who has trained with heavy weights. Not coincidentally, a new type of trainer was making his entrance onto the boxing stage—the “strength and fitness coach.” Without the usual cadre of old school trainers—most were either dead or retired—to bring this misguided trend to an end, weight training soon became an accepted part of a fighter’s regular conditioning program.

In the late 1980s Evander Holyfield further popularized weight lifting for boxers when his management decided to hire former bodybuilding champion Lee Haney to increase the former cruiserweight champion’s strength and weight in preparation for his entry into the heavyweight division.

By the 1980s Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky had morphed into a muscle bound body builder (MGM/UA Entertainment).

In the ensuing years many of boxing’s biggest stars have gotten on the bandwagon. Oscar De La Hoya, Fernando Vargas, Shane Mosley, Mike Tyson, Jeff Lacy, Shannon Briggs and Arturo Gatti have all hired strength and fitness coaches to help them fine-tune their bodies for ring combat. And judging by the proliferation of barbells and weight machines commonly found in boxing gyms these days, many other fighters are either employing strength coaches or lifting weights on their own.

Most of the strength and fitness coaches have no experience working with professional fighters. Their background and experience involves training athletes in other sports. Aside from their lack of boxing expertise, what they all have in common is an emphasis on weight lifting to increase the strength and power of the athlete.

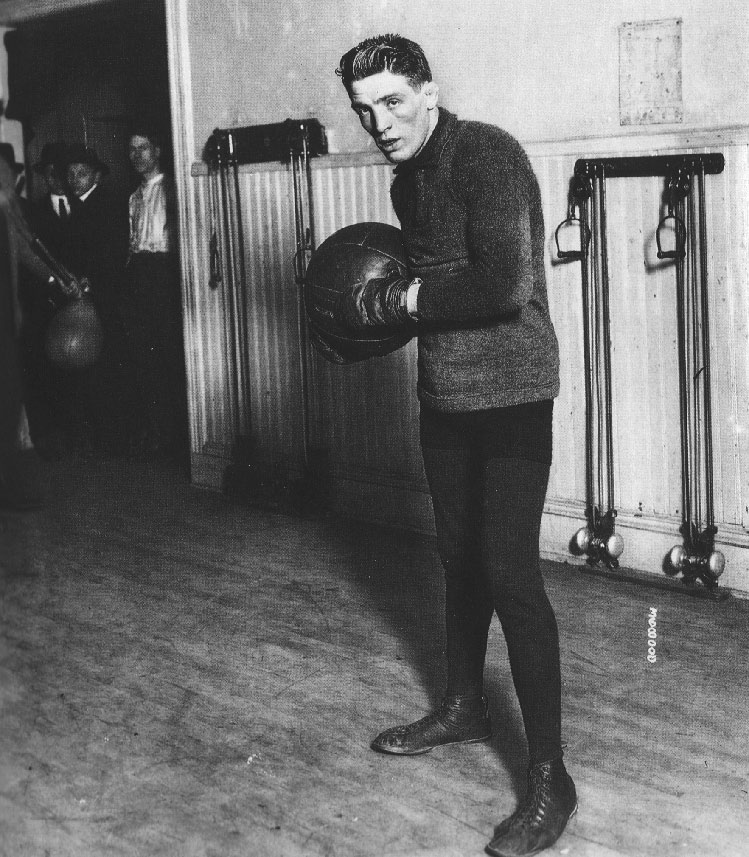

Prior to the 1980s the only weight training equipment seen in boxing gyms were light wall pulleys and the 12 pound medicine ball, as in this 1920 photograph of former welterweight champion Ted Kid Lewis.

Old school boxing trainers always frowned on weightlifting for fear it could lead to the dreaded “muscle binding.” Their fears were not unfounded. The muscles of a properly conditioned fighter are highly refined and attuned to the unique requirements of his sport. Weightlifting was seen as counterproductive because it slowed down reaction time and speed by creating unnecessary muscular tension, thereby interfering with the finely coordinated motor-neuron skills necessary for the split second moves in boxing.

Traditionally a boxer’s primary fitness goal was to attain the maximum in speed, endurance and power. Muscular development and strength was a byproduct of the normal training routine. However, not all weight-bearing exercises were off-limits to boxers. Working out with two to five pound dumbbells, wall pulleys (two to 15 pounds), or a 12-pound medicine ball was common.

If an underdeveloped boxer required additional strength, some trainers would have him exercise with weights that rarely exceeded 25 to 50 pounds. When the desired results were achieved the boxer would cease lifting and continue with his normal routine. It was important not to sacrifice speed for strength.

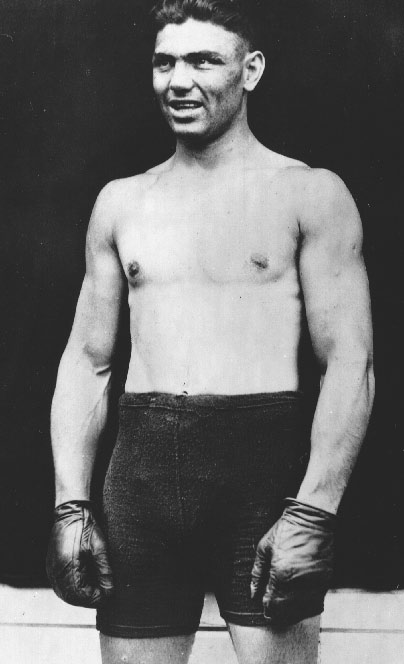

Old school trainers understood that pumping up the size of arm, back, leg and shoulder muscles with an aggressive weight-training program did not correlate to an increase in power. Punching power is a function of balance, leverage, coordination, speed and timing. A boxer has to be able to “snap” his punches. The most effective punchers in the history of the sport—Joe Louis, Jack Dempsey, Rocky Marciano, Sonny Liston, Jimmy Wilde, Bob Fitzimmons, Stanely Ketchel, Sugar Ray Robinson, Sandy Saddler, Archie Moore, Henry Armstrong, Bob Foster, Alexis Arguello, Roberto Duran—never included weight training in their daily workout routines. None of these super punchers had the type of unnatural bulging muscularity one often sees among today’s boxers.

Mike Capriano, Jr.: “Old time fighters had a sleek shape. They were not carrying extra weight through muscle. Fighters in the 1920s through the 1950s, heavyweights included, were trimmed down. They had long, smooth muscles. There was no need to oxygenate big muscles.”

A properly trained boxer is built more along the lines of a buff dancer than a tightly knotted bodybuilder or beefed up football lineman. In terms of their coordination, balance, footwork, flexibility, rhythm and timing, boxers have much in common with dancers. Professional dancers never train with weights for the same reason that boxers in the past did not. In their primes, three of the greatest boxers of the 20th century, Sugar Ray Robinson, Willie Pep and Muhammad Ali, could have easily been mistaken for members of a professional ballet troupe.

International ballet star and former amateur boxing champion Edward Villella in 1958, displaying the type of muscularity suitable for dancing or boxing (William Vassilov).

“Boxing’s appeal is its drama and grace, a blizzarding grace that amounts to an impromptu, exigent ballet, especially in the lighter and nimbler weights,” wrote essayist Edward Hoagland almost 40 years ago. “Hands, arms, feet, legs, head, torso—more is done per moment than in fast ice hockey; and since there is more motion, the athletes in other sports cannot surpass a consummate boxer for grace.”1

In the mid–1950s Edward Villella was the welterweight boxing champion of New York’s Maritime College, undefeated in 20 fights. Villella has since gained international fame, first as a lead dancer for the New York City Ballet under the direction of the legendary George Balanchine, and more recently as director of the acclaimed Miami City Ballet Company. Having experienced both the boxing ring and the ballet stage, Villella understands the unique training requirements of both disciplines.

Edward Villella: “I have never asked my dancers to do weight training. As dancers, we have long use of the muscle tone. We don’t want to short the muscle tone. We want speed and elasticity. I don’t think that you have to dismiss all weight training. You can exercise with four or five pounds, and you’d be surprised what that will do for you. When I was a dancer I’d occasionally put a one or two pound weight on either ankle. And then when I took them off my speed was just terrific, and my feet moved so quickly. And that’s what we need to do; we need our feet to move. Our feet are like a fighter’s hands. My great mentor George Balanchine said, ‘The floor upon which we dance is the music,’ which is the timing … it’s the phrasing. The dancer does not stay in one rhythm. You have to move in and out, in and out, up and down, slow, fast, set it up, go, go, go.

“Without a comprehensive understanding of your muscle tone, and the purpose of exactly what it is that you want to accomplish with a weight training routine, you could end up training against yourself. You don’t want the training to go against your talent. That is the thing you cannot do. You have to understand your talent and know how to feed it. And that is why I don’t want our guys to do that kind of thing. Guys are normally thicker muscle toned than women and I don’t want them to bulk up because they will lose that agility. Boxers and dancers are finely tuned instruments. Lifting weights would not be good for them. It’s like putting sand in the gas tank of a Ferrari.

“What we seek is to eliminate tension. If you train against that purpose it’s not going to work for you. For instance, if I were preparing our dancers for a style that requires very quick and light footwork, their training would be different than what is needed to dance in the much slower 19th century Russian Grand Imperial style. There is heaviness to that style. The moves have a beginning and an end, and then you start all over again. Whereas in neoclassicism, which George Balanchine provides us with, the moment your heel got to the floor that was your propulsion for the next step, therefore the continuity of it had terrific natural connection. So you didn’t ‘stop, gesture, stop, gesture.’ It’s like when you watch a heavyweight. They wind up and throw a big punch but they have no combinations. These guys are huge and they have four yards of left jab but it’s just hanging on ’em. They can’t go low, high, down. They can’t get that jab working. Pump that jab. Work those combinations … boom, boom, boom [demonstrates by shadowboxing and throwing combinations]. I relate to that kind of attack and speed.

“There is a whole connection about the approach to any physical gesture that we are about. It’s all totally connected and if you can be relentless in the way you approach these rotations, so that they are there and available for you any given second, you begin to dance instead of just doing a trick. And for me that is what differentiates fine dancing and fine fighting. It’s not enough that you’ve got a heavy right hand and a neat left hook and you throw two punches. There is more to it than that.

Rock hard Jack Dempsey, pictured in 1919, possessed the perfect build for a boxer—or dancer.

“My dancers have a repertoire where we have to dance in probably five, six, seven different styles, seven different periods, seven different choreographic approaches. They have the variety and they have the broader horizon. That was the beauty of my growing up at the New York City Ballet, which had a phenomenal repertoire. I danced everything from Swan Lake to tarantellas. You can’t get further away from being Oberon in Midsummer’s Night’s Dream to being the Prodigal Son, or Apollo. So unless you can counter and balance off all of these other things, you become a one trick pony.

“Dancing, as George Balanchine said, is a conversation; I offer a hand, somebody gives me their hand. Do I hold the hand, or do I just use what is necessary? For instance, if we are having a conversation I’m not going to shout at you the whole time. Nor am I going to talk like this [speaks haltingly]. So you have to have all of those ups and downs, sideways, expansions, extensions, all of this kind of flexibility that constitutes the purpose that you are about.

“But it’s really your mind driving your talent. So you need the talent and you need the mind that comes with the talent. It’s not like you’re trying to be a brain surgeon, but you need dance intellect just as you need boxing intellect if you are going to reach your potential. You need the intelligence that relates to your talent. And if you can combine that talent and that intelligence you are so far ahead of the game. So it becomes this mental exercise. I’m fond of saying our physicality is ‘mind driven.’ It’s not just the talent. It is the mind analyzing the talent, and all of the nuances that are available can be used.

“Dancing, like boxing, is moving through balance. And the athlete that you remember is the beautiful dancing athlete. I once took a bunch of athletes and intercut them with dancers and made it into a whole one-hour show. It was called “Dance of the Athletes.” Joe DiMaggio covering center field. His swing when he was at bat. Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Frank Robinson. These, to me, were the athletes who were the dancers. My favorite boxers are the ones who move and are beautiful to watch. The way Sugar Ray Robinson executed his combinations … the speed and accuracy … the timing aspect of it … the way a good defensive fighter could stand in front of somebody and bob and weave and pull their chin back, maybe just a quarter of an inch, and the punch would miss them. To me, that is absolute talent, which is so practiced, so rehearsed, so completely understood it becomes a conditioned reflex.

“Unfortunately, with my schedule, I rarely get to watch the fights today, and I can’t follow them. There was a fight on the other night, but it was all one sided. Let’s face it, a lot of the matches today are awful. They’re mostly mismatches, and it’s all setting up for the big payday, and to me that’s not what it’s all about.

“My father ran a trucking business in the garment center and his two closest buddies were former professional fighters. And they used to have poker games every Friday night and in the middle of the poker games the Friday Night Fights came on. Everybody stopped to watch the fights on TV and when it was over they went back to the poker game. I remember seeing great fighters like Willie Pep and Sandy Saddler, Tony Zale, Rocky Marciano, Carmen Basilio, Kid Gavilan and his ‘bolo punch.’ I can’t even think of all the names now.

“When I was an amateur boxer in college I had a tremendous advantage because I had trained as a ballet dancer for about seven years. Therefore, my legs were mine. They were in terrific condition for boxing. I’d wait until the third round and by then my opponent would be standing on spaghetti legs [laughs].”

Speaking of dancers, anyone fortunate enough to have seen master boxer Carlos Ortiz in his prime can attest to his beautifully coordinated and precise choreography in the ring.

Carlos Ortiz: “I never lifted a two pound weight in my entire fighting career. Weight lifting is not appropriate for fighters. It tightens your muscles. You stiffen up and get muscle bound. A fighter needs loose muscles that unlock and move. Weightlifting is something that shouldn’t be done. I never saw a fighter lift weights in my time. There is no comparison between a fighter, a football player, a baseball player or a golfer. Boxing is by itself. What you are trying to do is not get hit. The guy is throwing punches at you. You have to be very smart and fast to duck, shift and not get hit. Weight training doesn’t fit in.”

Mike Capriano, Jr: “I think using weights militates against the appropriate training that is required to be a boxer. That does not mean that we never did weight training. Boxers used light dumbbells of two to five pounds, and worked out with the medicine ball and wall pulleys. But the scientific answer is that if it develops muscles that slow down speed and negatively affects punching power, then it’s not a good program.

“Build yourself up a bit,’” the old trainers would say. And of course there is an element of strength involved. After all, you cannot be a weakling if you are going to box. But I don’t know that the design of reaching strength is solved by the methods being taken today by so many fighters. Up until about ten or fifteen years ago barbells were never in a boxing gym.

“The fighters today need rounds in the gym more than they need weightlifting. Doing presses, curls and other exercises with weights is not real conditioning for boxers, even with light weights, because many fighters are naturally strong and don’t need it. Few fighters were as muscular as Emile Griffith and Emile never lifted a weight in his life. In those types of naturally muscular physiques you didn’t want any more over development.

“Weight training increases the amount of oxygen required by the muscles. It also limits the amount of punches thrown and slows down the speed of the punch. We do not want bigger muscles if it comes at the expense of speed. Strength training is not making the fighter better if he loses speed. It is just trying to take shortcuts. And the fighters may actually be over straining their bodies with this type of training. It is not natural. Light weights at the end of a pulley system are OK, as is work with the medicine ball.”

Three of the strongest Golden Age fighters—Jake LaMotta, Rocky Marciano and Beau Jack—never lifted weights during their pro careers. (The information on La-Motta comes directly from “The Bronx Bull” himself.) Charlie Goldman, who trained and conditioned Marciano throughout his pro career, always espoused traditional methods. Beau Jack told this writer in 1997, “I never trained with weights because it slowed you up and tightened you up.”

In 1981 Salvador Sanchez, possibly the best featherweight champion of the past 35 years, told a reporter, “I don’t lift weights because it stiffens and slows the arms.”2 The lean and wiry Sanchez was built like a ballet dancer. Two of his top challengers, Wilfredo Gomez and Azumah Nelson, were both physically stronger and more muscular. Sanchez stopped both of them.

Harold Johnson (light heavyweight champion from 1961 to 1963) possessed the body of a Greek god. But he was quick to point out that weights played no part in carving his outstanding muscular definition. “The only weights I lifted were dumbbells for shadow boxing to put power in my punches. I was told I could hurt myself lifting weights, so I didn’t. I didn’t want to get injured.

“It’s not good for fighters—it makes you slow, muscles you up. They might give you power, but your opponent will see your punches coming. What’s the point in having power if you can’t hit nobody? People were sure I lifted weights, but I never did.”3

Teddy Atlas: “A lot of people who think that weight training was completely taboo, that the fighters did not use any weights in the old days, are wrong. It’s not true. The old time gyms had those light pulley weights. Almost all the gyms had them. And here’s the funny thing; with all the genius, and all the technology, and all the degrees that these strength coaches have, or whatever the hell they are—and most of them are bullshit artists—with all that, whenever something goes wrong they will tell you, ‘The fighter made a mistake and was put on too heavy a weight and it bulked him up and he lost his flexibility. So we’ll adjust his workout and put him on lighter weights.’ “A lot of these weight coaches are driven by their egos, so when the fighter gets on TV they want to say, ‘Look what I did to his body.’ But I notice that whenever there is a problem, the first thing they will say is that the weight training ‘bulked him up, it stiffened him, he lost his flexibility, he lost his speed. He should have been working with lighter weights’—which is exactly what the guys did in the old days, where it was part of their training regimen but with much lighter weights than what the fighters are using today.

“I think the problem comes down to this: Nowadays, instead of putting your eye on the ball, so to speak, and having to deal with what is going to make you a better fighter, there are too many searches for that magic drink from the fountain, that ‘purple liquid’ that you’re going to swallow and it’s going to make everything okay. Without the fighter or his management realizing it, they are undermining their own fighter. Instead of making him accountable in the areas that he needs to improve, they go looking for shortcuts.

“I’ve had fighters who have gone looking for the magic formula. I tell them, ‘You need to save your money to take that plane trip.’ And they say, ‘What plane trip? What are you talking about’? I say, ‘Tibet or Turkey, or wherever the freak you’re going to find that root. You’ll climb over that mountain and walk for about ten miles and then you’ll finally see this little tree and it’s going to be glowing and you’re going to pull this root and you’re going to chew on it and it will make everything go away. But you don’t understand. There is only one place you have to look for the power and that’s right in that mirror. That’s where you’ve got to start focusing on. Your problem is you’re looking for something else to make it for you but it’s right there. It’s you! Try to condition yourself instead of bringing something else in to change the condition. Try conditioning yourself.’ And that’s part of what’s happened.”

One of the fighters who went in search of the “purple liquid” cure Teddy Atlas speaks of was Fernando Vargas. After winning a Bronze medal in the 1996 Olympic Games, Fernando Vargas took the professional boxing world by storm. His aggressive style, engaging persona and fighting spirit won him a legion of fans. Vargas was a brilliant prospect. If he had fought during the Golden Age his career would have progressed in increments. After some 40 or 50 bouts, he’d be a seasoned contender and ready for anything. Instead, less than two years after turning pro, in his 15th fight, he won a Junior Middleweight title belt.

Unfortunately for Vargas, standing in his path was the equally talented but far more experienced Felix Trinidad. Each owned a portion of the junior middleweight title. Their mega fight showdown was set for December 2000.

Vargas’ management had good reason to be worried. On the plus side, Fernando was physically stronger than Trinidad and possessed knockout power. But so did Trinidad. They knew their undefeated tyro would be in for the toughest fight of his life. The “purple liquid” beckoned. Why not take advantage of the latest methods in conditioning and strength training for athletes in order to give Vargas an edge? Why not do like the professional football players do and hire a strength and fitness coach?

Enter John “Doc” Philbin.

Doc Philbin’s credentials were impressive—that is if you weren’t too concerned that his background and training had absolutely nothing to do with boxing. Philbin had worked for pro football’s Washington Redskins for seven years (1993–2000) as an assistant to head strength coach Dan Riley. Prior to his work with the Redskins, he was head coach for the 1992 winter Olympics bobsled team, establishing the fastest push times in the world. Philbin also worked with world-class sprinters and had written two books on strength and conditioning for the elite athlete. He had an M.A. in physical education and was a former collegiate decathlete. Yet nowhere in his curriculum vitae was there any mention of boxing, a sport whose technical complexities and physical demands are very different from football, track and bobsledding.

Ironically, the one area that Vargas was clearly superior to Trinidad, even before Doc Philbin entered the picture, was his strength. Vargas did not need the services of a strength coach. What he did need (aside from more experience) was an old school boxing coach who could instruct him how to make the best use of his superior strength.

Felix Trinidad’s style is especially effective against aggressive boxers who pressure him, which just happens to be the way Vargas fights. As expected, he made a beeline straight towards Trinidad. Vargas came on strong, especially in the early rounds, but Trinidad kept his cool and scored with accurate and damaging counter punches. The fight turned bad for Vargas after the sixth round. Over the next five rounds he took a severe beating. The fight was stopped in the 12th round. The next day Philbin and Vargas terminated their relationship.

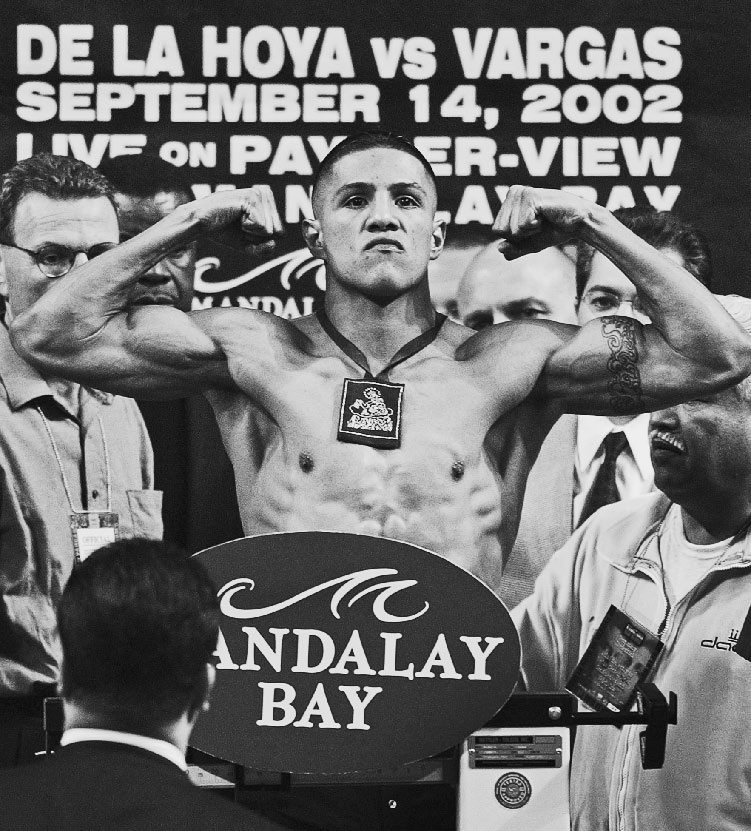

Two years later, Vargas, on the comeback trail, challenged Oscar De La Hoya for his version of the Junior Middleweight title. Time may have healed the physical and psychic wounds of the Trinidad debacle, but it did little to add to his experience. Vargas had fought just twice in the 21 months leading up to the bout with De La Hoya.

At the weigh-in Vargas was brimming with confidence. He called attention to his low body fat percentage and his impressively “cut” physique. He certainly looked stronger than De La Hoya, who appeared almost soft by comparison. But what no one knew at the time was that Vargas had surreptitiously taken illegal steroids to enhance his strength. This fact was not revealed until he tested positive for the drug after the fight. Obviously, Vargas felt that strength training alone was not enough. He wanted the extra boost that steroids would provide.

It was apparent from the opening bell that an energized Vargas was attempting to overpower De La Hoya and pressure him into a close quarter slugging match. De La Hoya had to call upon all of his experience and strategic acumen to cope with a physically stronger challenger who was intent on destroying him.

Although he was more aggressive than De La Hoya, Vargas was often wild and inaccurate with his punches. De La Hoya used evasive footwork and punishing left jabs to keep the fight at long range. He also managed to tie up Vargas on the inside, thereby nullifying his greater strength.

In the sixth round an enervating fatigue seemed to overtake Vargas. Had the tough Mexican punched himself out in his mad desire to destroy De La Hoya? It certainly looked that way. Vargas, exhausted and nearly defenseless, was knocked down in the 11th round by a powerful left hook. He beat the count but upon arising took 16 unanswered punches before the referee stopped the fight. Oscar De La Hoya had conceded strength to Vargas but not skill, experience or toughness. Even with the illegal drug boost Vargas could not gain the edge he needed to overcome a superior ring technician.

Fernando Vargas flexes his muscles prior to his showdown with Oscar De La Hoya in 2002. Despite taking illegal steroids, Vargas could not gain the edge he needed to overcome a superior ring technician (AP/Wide World Photos).

Fernando Vargas had deluded himself into thinking he could somehow override De La Hoya’s greater experience by ingesting steroids. Vargas and his management forgot (or more likely never knew) that the name of the game is boxing. Any old school trainer could have told them that muscles and machismo will only take you so far in a boxing ring.

Teddy Atlas: “Not too long ago I was very upset with a fighter I was working with and I said to him, ‘You know what your problem is? It’s the same problem with a lot of people, not just fighters. You are looking for someone else’s weakness to be your strength. That’s the problem with all you guys.’ You see, they don’t like to hear that. They don’t even know what the hell you’re saying at first, but they sure as hell don’t like to hear it. This was true for Mike Tyson as well. Tyson depended on others to be weak for him to be strong.

“Fighters take steroids not just for the physical advantages but because of what we have been talking about throughout this whole book—what the old-timers had and these young guys don’t have. They want to give themselves a way of being confident and a way of saying ‘I’m okay’ instead of being okay. They are seeking another way to be mentally together, confident, and ready to behave like a pro. When these guys grab onto these things they’re feeding their weakness instead of developing a strength. They don’t realize that because what they are basically saying is, ‘I can’t depend on myself.’ That’s what they’re saying. And that’s what I’m saying is at the essence of this whole argument: The greatest strength that these old time guys had over these guys was the ability to depend on themselves. That was their greatest strength—the ability to depend on themselves.

“When these guys are grabbing the steroids, the creatine, the growth hormones—or whatever—trying to get bigger what they’re basically saying is ‘I cannot depend on myself.’ They are saying the one thing that the old timers never said. The one thing that the old timers knew was at the forefront of anything they did was, ‘I can depend on myself when I walk out of that locker room, and walk up that aisle, and walk up those steps. That was the one thing that they embraced and that they always brought with them. All of them. Using steroids is the antithesis of that. They’re saying, ‘I cannot depend on myself. I cannot even get myself in the ring without at least thinking that I have some help.’ Old time fighters knew where the help was. It was in the development of them … in the truth of them.”

The usefulness of steroids to enhance a boxer’s performance has not been established. Unlike a baseball player whose steroid pumped muscles enable him to smack a home run into the stands, or a juiced up sprinter who explodes out of a starting block, the complex physical and psychological demands of professional boxing appears to place limits on the drug’s ability to establish a clear advantage when so many other factors are involved.

Perhaps it was the steroids that caused Vargas to fight so intensely and at such a terrific pace in the early rounds of his fight with De La Hoya. He seemed unable to slow down even if he wanted to. Over the last four rounds an exhausted Vargas, his muscles depleted of oxygen, could only fight in spurts.

Shane Mosley, who started his career as a 135-pound lightweight, has admitted lifting weights to increase his size and strength so he could compete in heavier divisions, thereby accessing more lucrative fights. Before his second fight with De La Hoya, in 2003, reporters were told that Shane was lifting weights to develop a “deeper chest.” This made no sense whatsoever. Was Mosley in a pectoral contest with De La Hoya? There is no correlation between a deeper chest and boxing strength or power. Statements like this point to the ignorance that is pandemic in boxing today. But with athletes in other sports benefiting from weightlifting and drug supplementation, many fighters believe they are missing out on something that could improve their performance. Fighters are using these methods to gain unnatural weight in order to compete in divisions their builds are not suited for.

Oscar De La Hoya started his pro career in 1992 after winning an Olympic Gold Medal in the 130-pound junior lightweight class. Five years later, weighing 146 pounds, De La Hoya took the welterweight title from Pernell Whitaker. The weight gain could have been natural, but a fighter moving to a heavier division is always concerned that he will not be strong enough or powerful enough to compete successfully at the new weight. Old school fighters compensated by gaining a few pounds through diet and, most importantly, utilizing boxing strategy and speed to win. They did not try to outmuscle the stronger fighter, which, in the absence of quality instruction, is what most fighters are attempting to do today.

In 1999 De La Hoya admitted to using creatine to increase his muscle size and strength and “something else” to increase his testosterone levels in preparation for his welterweight showdown with Felix Trinidad. “His body has changed, all of the weight has moved to the top,” said Gil Clancy, the well-known boxing trainer, who is not a proponent of weight training or drug supplementation for boxers.

Creatine is a natural substance that mimics steroids. It is supposed to keep an athlete exercising beyond his normal fatigue limits. Unlike steroids, the use of creatine is not illegal. Scott Connelly is the owner of MET-Rx, a company that manufactures creatine. Connelly said that De La Hoya came to his company because he wanted to enhance his physical performance in terms of strength and endurance and noted, “Within six weeks there was a major transformation in his body.” According to Connelly, other boxers have come to him to use his performance products, including Lennox Lewis, Evander Holyfield and Mike Tyson.

Whatever De La Hoya was taking, it apparently failed him in his fight with Felix Trinidad in 2000. He displayed a puzzling lack of stamina in the last three rounds that cost him the fight. De La Hoya claimed it wasn’t fatigue. He told reporters he made the mistake of coasting because he thought the fight was already won. But the same thing happened to him in his second fight with Shane Mosley in 2003.

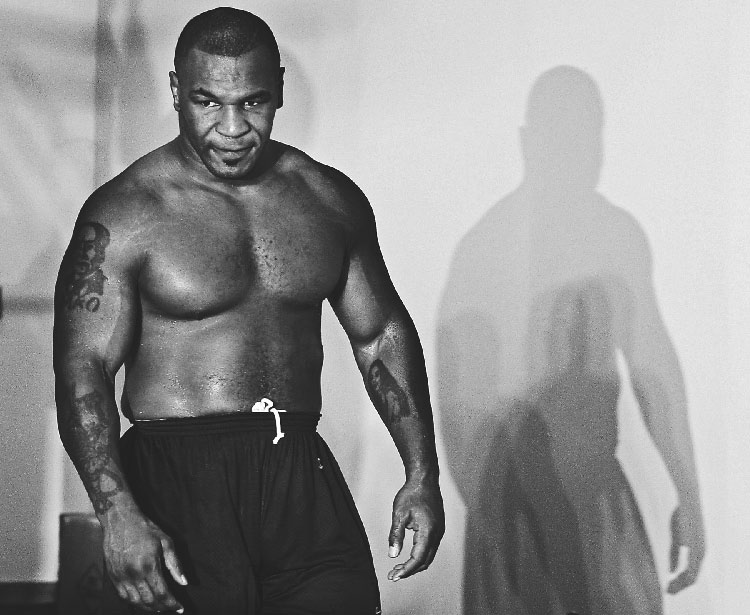

Cus D’Amato, Mike Tyson’s original trainer, did not attempt to enhance Tyson’s natural strength with weight training or steroids. Years later, with D’Amato long gone, and nearing the end of his tumultuous career, Tyson began strength training with Gunnar Petersen, a Los Angeles based strength coach popular with show biz types.

Putting Tyson on a strength training regimen was about as necessary as importing ice cubes to Alaska. In a few months Tyson had added 20 pounds of unnecessary muscle to his stocky frame. The ex-champ was convinced the “purple liquid” would enable him to recapture his prime and restore his confidence.

Mike Tyson as he appeared just days away from his disastrous 2002 fight with Lennox Lewis. Unnecessary strength training added superfluous weight and muscle more suitable for pro wrestling than boxing (AP/Wide World Photos).

The following description of Tyson appeared in the New York Post on October 12, 2001: “His upper torso cut like that of a bodybuilder and his waist trim and taut, Tyson tipped the scales yesterday at 239 pounds for tomorrow’s 10 round bout against Denmark’s Brian Nielsen.” It was pointed out that although Tyson was at the heaviest of his career, he also “might be in the best shape.”

The 260-pound Nielsen—nicknamed “Danish Pastry” by the press—was knocked out in the seventh round. Tyson was pleased with the result and continued working with Petersen in preparation for his upcoming title fight with heavyweight champion Lennox Lewis in June of 2002.

If Tyson had challenged Lennox to a bodybuilding competition instead of a prizefight, he would have won in a walk. In a photo taken just days before the fight, Tyson was shown sporting gargantuan pectoral and biceps muscles. He was built more along the lines of Hulk Hogan than a serious challenger for the heavyweight championship of the world. Not even Primo Carnera, the poster boy for muscle bound fighters, had ever appeared so bulked up.

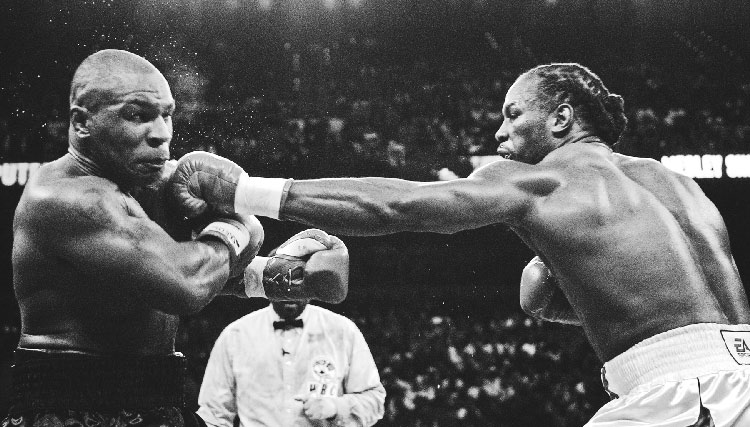

Tyson’s fearsome reputation had Lewis fighting very cautiously, even though every punch Lewis threw found its mark. Iron Mike appeared about as flexible as iron as he struggled in vain to mount an effective offense. His once vaunted punches were thrown without speed, precision or knockout power. The few punches that did land had no effect on Lewis. Tyson absorbed a frightful beating. The mismatch finally ended in the eighth round with Tyson flat on his back taking the ten count.

Mike Tyson (left) on the receiving end of a Lennox Lewis jab. Overweight and over muscled, Tyson was stiff and slow. He took a brutal beating before being knocked out in the eighth round (AP/Wide World Photos).

Mike Tyson was washed up before he ever stepped into the ring with Lennox Lewis, but his absurd training methods dashed any iota of hope of his ever winning back the title. He did not need additional weight and muscle. What he needed was less weight and more speed.

Arturo Gatti is the latest big name fighter to succumb to the lure of the “purple liquid.” Gatti, 35 years old and in the twilight of a colorful roller coaster career, hired strength and conditioning coach Steve Cruz to help him prepare for his welterweight title fight with Carlos Baldomir in 2006. In addition to having him lift weights, Gatti’s strength trainer incorporated swimming into his routine. He also had Gatti do a series of very fast push-ups in order to develop what he called “explosive power.” Shades of Rocky Balboa!

Arturo Gatti was only deluding himself. The gutsy fighter had been to the well once too often. No amount of “purple liquid” was going to turn back the clock. In his prime Arturo Gatti would have been a good bet to outfight and out hustle a fighter of Baldomir’s limited ability. The 2006 version of Gatti lost nearly every round to Baldomir before being stopped in the eighth round. There was no “explosive power.” The unusual training methods may have actually done more harm than good. Gatti had never looked so bad.

Former heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield has had an on again, off again relationship with his strength coaches. I cannot say for sure if it was strength training, steroids, or something else that created Holyfield’s stamina problems. This writer is of the opinion that weight training hurt Evander more than it helped him. He was still able to win important fights thanks to his enormous fighting heart and the weakness of the heavyweight division. In other words, Evander succeeded in spite of, not because of, his work with strength coaches.

Erik Arnold: “Did the weight training improve Evander Holyfield’s stamina? Did he become a harder hitter? What do I think of weight training for boxers? Nothing. If anything it makes these guys slower and more ponderous because they have these massive sculpted muscles, which really aren’t right for boxing. Look at Bob Fitzimmons and Jack Johnson. They exercised using traditional methods rather than a specific body-toning regimen and they were probably stronger and tougher than any of these muscle men today. Take 1970s heavyweight contender Mike “Hercules” Weaver. He was a hard puncher but had no stamina and his chin was poor. All the muscles in the world didn’t help him. Ken Norton had a great build but a fairly bad chin. Rocky Marciano would have knocked all these guys out.”

Steve Lott: “The weight trainers are not addressing the real problem, and that is that the fighters don’t know how to fight.”

In his recently published book on training for boxers, Box Like the Pros, former heavyweight champion Joe Frazier expressed his aversion to weight training for boxers: “I’m more from the old school. God hasn’t made better fighters yet than Joe Louis, Henry Armstrong and Sugar Ray Robinson. And those guys never lifted weights. Neither did Jack Dempsey or Jack Johnson. I never lifted weights and I was plenty strong in there … fighters don’t need big muscles. Big muscles don’t mean anything. You’ve got to be able to fight. If you can’t fight, no weights and no strength in the world are going to help you in that ring. And if you can fight—if you’re in shape and committed and do what your trainer tells you—you don’t need big muscles. You already can fight. What do you need big muscles for? Plus, even if them muscles make you stronger, they can slow you down, too … I don’t tell my fighters to lift weights” [From page 46, Box Like the Pros by Joe Frazier and William Detloff. Copyright © 2006 by Joe Frazier and William Detloff. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers].

Despite Joe’s sage advice, the trend today is for boxers to copy athletes in other sports by integrating weight training into their exercise programs. It is not unusual to see boxers doing curls, squats and bench presses with 80 to 200 pounds. This is especially true in the heavier weight divisions.

Wilbert “Skeeter” McClure: “To me the idea of having a fighter lift weights to increase strength is like messing around with something that’s not that critical … not that important. I’m not saying that in all cases it’s not helpful, but for most cases it won’t help a fighter become a better fighter. And it will not help him become a better-conditioned fighter. You just have to look at boxing history and compare today’s fighters to the fighters who did not use weight training and who were tough and strong. Fighters like Joe Louis, Jack Dempsey, Rocky Marciano and Jersey Joe Walcott would destroy any of today’s heavyweights. In fact, any of the fighters I just named could probably fight each of the people in the top ten in one night and do quite well against all of them. Really.

“I never lifted weights. I chopped wood, but that was minimal. I did not do it every day. There needs to be a good justification for lifting weights. Running for endurance and knowing how to keep from being hit are more important priorities. Speed is probably the most important element in boxing. Most people don’t understand the correlation between hand speed and power. It’s the punch you don’t see that knocks you down, not the one you see.”

Emanuel Steward: “Many weight trainers and conditioners confuse the training techniques needed for boxing with the strength training needed for football and other physical sports in which strength training has been utilized for many years.4

“I am very upset about having these strength coaches involved with professional boxers. Shannon Briggs had a weight lifting coach that messed his shoulders up. You can throw 95 percent of them in the alley as far as I’m concerned. When it comes to boxing they don’t know what the hell they’re doing.

“Recently we were interviewing Fernando Vargas for HBO and he says, ‘Look at me here, you never saw a Mexican cut like this.’ He was so excited talking about his impressive looking physique and his strength trainer and nutritionist. When we finished up interviewing I said to him, ‘Fernando, are you doing any boxing?—Because this is all you’re talking about.’ And that is a perfect example. He was so wrapped up into his strength training and nutrition program that he totally lost focus that he was a boxer. I felt he definitely handicapped himself.

“It gets to be where these guys get in the way. I’ll say to a fighter, ‘We got to box some today and the fighter will tell me, ‘I’ve got to save some today. I’m working out with my conditioning coach at 6 P.M. tonight.’

“Another time I’m working with Oscar De La Hoya and I get a call from Oscar asking me what am I doing around 7:30. He asks me, ‘Can you come over’? I go over there and this strength trainer has a whole bunch of weights that he’s putting on his back and he’s got to do a squat with what looked about 300 pounds. I said, ‘What the fuck are you guys doing! Get these fucking weights off his shoulders!’ As soon as I told him to take that shit off his shoulders, Oscar jumped off and ran into the house like a little kid that was just rescued.

“Bob Arum, Oscar’s promoter, set up a meeting with myself and the strength coaches. I told them they were harming the fighter and as far as I was concerned they needed to get the hell out of training camp.

“To justify their existence at camp, and show that they were doing something, the strength coaches were always writing in these thick pads, detailing all of the stuff they were doing with the fighter, and then submitting the pages to Arum. They would say, ‘We were just reading a book and we realized that the “letoid” muscle that’s in the thigh is where the fighter throws his punches from, and he’s got to be able to propel the punches off of a quick pivot and a thrust from the leg muscles and by using these weights to come down to the angle we were using, we can then build up his thigh muscles and that way he can have much better power.’ I asked them, ‘Where did you learn that? You read that in a book?! What you are doing here is experimenting on a fucking top athlete!’ And that is what most of them are doing—experimenting. That is all they are doing. I told them, ‘No more fucking weights’!

“Look at Tommy Hearns, Bob Foster, Joe Louis and all those great punchers. They are usually rangy guys. Even Foreman was a loose, naturally strong kid. They didn’t have these tightly muscled builds that came from lifting weights.

“A heavily muscled boxer like Frank Bruno after a certain amount of rounds in most of his fights nearly collapses from exhaustion. Even when he won the title the whole crowd tried to cheer him on so he wouldn’t get knocked out the last round, he was so tired. It’s because he lifts weights. When Michael Grant was coming into the ring to face Lennox he looked at Grant and said to me, ‘Well, I got me another one of my muscle babies.’

“Fighters like Grant and Bruno are so tight they can’t get their punches off normally. And after about five or six rounds their muscles become fatigued. A fighter also takes a chance tearing his muscles by weightlifting.

“I looked at Vargas after the sixth round of his fight with Oscar and realized he wasn’t even reacting. He couldn’t even block punches, couldn’t even move his arms to pick them off. When they ended up stopping the fight Oscar was pouring it on and Vargas was up against the ropes with his hands up but he couldn’t defend himself. And that’s what the weightlifting does. It gives you that temporary feeling of being strong with your push punches.

“Weightlifters don’t have good punching power because they push their punches. They may look strong but they don’t really punch hard. And they tire very quickly. So as far as I am concerned they can give me my old methods whereby a fighter gains physical strength by boxing with another guy his own weight, exchanging punches, blocking punches, pushing each other, going to the ropes. You develop the necessary strength from dealing with that.

“Most fighters are already naturally strong. Are you telling me the old method of beating on those heavy bags, skipping rope, hitting the speed bag and such—all of a sudden that’s outdated?”

Ted Lidsky: “A lot of fighters today think that lifting weights will improve their punching power. But no one has ever been able to figure out why some fighters punch harder than others. So if it isn’t really understood what makes one fighter punch harder than another, how can you use weights to work on particular muscles to develop a skill that no one fully understands? There are boxers who are strong enough to pick up a Volkswagen but they can’t crack an egg with their punch. These things are more fads than they are science. It’s the same thing with diet. For a while we had the carbohydrate loading craze. Everybody thought that was the proper diet for endurance sports. Now the thinking is back to having protein before an athletic event, and less carbo-loading. Well guess what? That’s the way fighters used to eat in the old days.”

Freddie Roach: “If you work out correctly you don’t need to lift weights. I think its bullshit. If you do your job properly, if you run hard, work hard in the gym, do your exercises as a fighter, I think you are doing more than enough, as long as you do your job correctly. I’m not just talking about going into the gym and shadowboxing a few rounds and going home. I’m talking about working hard, getting proper sparring and so forth.

“A big problem is that every strength coach in the world comes from a football background and it’s just such a different sport. Muscles don’t create punching power at all. I just don’t agree with it. I know Holyfield has been doing it. And even my guy James Toney was doing it for a short time. When he first came back into the gym he was tight and slow and I said, ‘James, what are you doing? This isn’t you.’ He said he was lifting weights to get a better physique because people were saying that he looked fat. I told him, ‘who gives a damn what you look like as long as you can fight like you can fight! You are going to get rid of all that bulkiness and tightness.’

“Speed is the asset, especially for a guy like James Toney. All these guys want to look like bodybuilders but looks and muscles don’t create power or speed. My trainer, Eddie Futch, was against weightlifting, my father was against weightlifting. I did very little weightlifting. I’m a strong person physically because I’ve been punching the heavy bag and working out my whole life.”

Bill Goodman: “Years ago you had fighters that never trained with weights and they turned out to be great fighters. But the trainers can’t teach today. They can’t show a fighter anything that would school him properly. So they compensate for this lack of knowledge by making up new fangled ways to train. They have him go out and run 15 miles and pick up weights and do all types of strength training because they’ve got nothing else to offer the fighter. They bring the fighter to a strength trainer. They did that with James Toney and he still lost. They’re full of crap. Jack Dempsey didn’t go to a strength trainer. Benny Leonard didn’t go to a strength trainer. It’s crap. The trainers don’t know what to do anymore. They make this stuff up but it doesn’t help the fighter.

“Years ago they tried to concentrate their effort in improving the fighter. The trainers schooled him boxing wise. Today they try to make up for that lack of ability by concentrating on excessive physical conditioning. In many cases it’s too much punishment for the body. They are putting too much effort in the wrong direction. The real problem is they don’t have the skills to teach a fighter. And who’s responsible for that? These amateurs that have come into the sport in recent years. Like that guy in a Miami gym who had his fighters hitting bubbles. It’s ridiculous. One old time trainer almost collapsed when he heard about it.”

Tony Arnold: “One of the reasons this is the worst era in the history of boxing is because you have the wrong ideas on training. The fighters of today are all in good condition for the type of fights they have. For example, Jermain Taylor was in good condition for his fight with Winky Wright. But Taylor was not on the go all the time. What I mean is none of these fighters have been put under extreme pressure, which makes a lot of difference. If they had to fight at a little harder pace I don’t know how they would react. Even De La Hoya and Holyfield had trouble going a fast 12 rounds.

“I think the old methods encouraged stamina more. A lot of time was spent on conditioning the legs and on stamina. A lot of fighters today spend too much time on strength training with weights and bulking up. Ray Mancini, towards the end of his career, was one of the first fighters to work with weights. He depended on strength and aggression. But the training slowed him down. It was completely contrary to the old style of doing things. The old time fighters proved they could fight longer. I doubt if a lot of these guys could go a hard 15 rounds.”

If Sugar Ray Robinson, Muhammad Ali and Willie Pep were fighting today they would be told by their strength trainers to add more muscle and weight to their lean physiques in order to compete against bigger and stronger opponents. Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano, Jersey Joe Walcott, Ezzard Charles and Joe Frazier would be considered “too small” to compete against the likes of Shannon Briggs, Sam Peter and Wladimir Klitschko. After three months lifting weights and taking various supplements, they’d all be looking like Mike Tyson clones. Of course their speed, punching power and coordination would be compromised, but they could at least take comfort in the impressive appearance of their new physiques. And of course the idiot chorus of faux experts would rave about how their impressively cut physiques proved they were in great fighting shape.

What would Charlie Goldman or Ray Arcel have to say about the following advice given by strength and nutrition expert Mackie Shilstone on how to enhance the muscle endurance of fighters? “Consider utilizing a load based on the ability to generate repetition somewhere between 10 and 30, depending on the fighter’s history of punches per round”5 How would the old school trainers react to conditioning coach Dave Honig’s belief that “fighters need to increase leg strength, which will increase the explosive power that enables them to deliver a more powerful punch.”6 No authentic boxing trainer ever talked like this. The advice is indicative of a very limited knowledge of the type of beneficial strength training required of a boxer.

Would training with weights have improved the performance or punching power of Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano, Marvin Hagler, Roberto Duran or Henry Armstrong? Could these fighters have possibly been in better shape for boxing than they already were?

And what is this obsession with body fat percentages that all of the strength and nutrition coaches seem to have? If a fighter is trained in the correct way there is absolutely no need to measure his lean to fat ratio in order to confirm that he is in top physical condition. A competent boxing trainer knows when his fighter is ready without having to measure his body fat.

Measuring body fat is just another form of irrelevant “window dressing.” Yet this useless information is often reported as hard news. Typical is this excerpt from the boxing web site SecondsOut.com describing Roy Jones, Jr., on the eve of his return match with Antonio Tarver: “Jones also came to camp at 190 and worked with conditioner Mackie Shilstone for six weeks prior to the fight. When they began their regimen, his body fat was 11.5 percent. By fight night, that number had been cut in half.”7 As it turned out, Tarver was not the least bit intimidated by his opponent’s impressive body fat percentage. He flattened Jones in two rounds.

Boxing scribe Kevin Iole devoted an entire paragraph in the Las Vegas Review Journal describing the history of Oscar De La Hoya’s body fat a few days before his title fight with Bernard Hopkins: “De La Hoya went into camp for the Sturm fight with 19.5 percent body fat and had 9.5 percent by fight time. By contrast, he had only 4 percent when he fought Julio Cesar Chavez for the first time as a super lightweight in 1996. De La Hoya vowed to have no more than 5 percent when he faces Hopkins.”8

In a follow-up article a week later, the news concerned the aesthetics of De La Hoya’s physique: “On Wednesday, De La Hoya’s midsection appeared cut and he looked as if he were in fighting shape.”9 Unfortunately, Oscar was unable to attack Hopkins with his impressive “six-pack” abs. Hopkins knocked him out in the eighth round with—of all things—a body punch.

Boxing reporting often focuses on such irrelevancies because the writers have a limited understanding of the sport. There is rarely any mention of possible strategies, comparisons to past champions or even an intelligent prediction on possible outcomes. Instead reporters cover for their lack of knowledge by parroting the fitness-babble of the strength and nutrition gurus.

Another convenient obfuscation is for newspapers and Internet sites to re-print the CompuBox “punch stats” that are announced at the end of every round of a televised fight. Example: “Taylor out jabbed Hopkins 64 to 29. But Hopkins had the edge in power punches connecting 101 to 60.” But why was Taylor able to out jab Hopkins? And how does a fighter connect with 101 so called “power punches” without having any effect on his opponent? For anyone who grew up reading the outstanding boxing reportage of Red Smith, Jimmy Cannon, Dan Parker, Ted Carroll, Frank Graham, Milton Gross, Lester Bromberg, Bob Waters, and Marshall Reed, what passes for boxing writing today leaves one in a profound state of despair. But in fairness to today’s reporters, their counterparts of decades past had an unfair advantage. They were fortunate to have access to knowledgeable trainers who could set them straight. Today’s boxing writers have few such resources. As a result, not only is the quality of boxers at an all time low, so is the quality of boxing reporting.

Ray Elson is a former world-class weightlifter. In the late 1960s he won regional and national amateur weightlifting titles and took first place in the Amateur Athletic Union Senior Metropolitan competition. Looking for new athletic worlds to conquer, Ray decided, at the age of 23, to become a professional boxer. Elson boxed for eight years in the light heavyweight division. In 1978 he made a decent showing against former light heavyweight champion Victor Galindez before being stopped in the eighth round. Ray Elson is one of the few people who can speak knowledgeably on weight training and boxing, having experienced both at the highest levels of competition.

Ray Elson: “When I came into boxing as a 175 pound light heavyweight, I was already very strong from my weightlifting. I had the strength of a heavyweight. If anybody tried to match my strength in the ring I had the edge. But I quickly learned that boxing was not about strength. And this is true of other sports, as well. In a sport such as collegiate wrestling the thin guy can beat the guy filled with muscles if he knows how to apply his strength and leverage. I also learned that a lot of boxers are big and strong, have a lot of muscles, but they can’t punch.

“Once I started boxing I had to retrain my muscles. You have got to become more supple. It has nothing to do with weights. Just hitting the heavy bag teaches your muscles. You strive for speed in boxing. While I was training as a boxer I never lifted weights. It would have been detrimental to my boxing if I continued to lift weights, especially heavy weights, definitely.

“I already had all the strength I needed. Doing heavy squats would have constricted my leg muscles—and you had to be supple and be able to move quickly on your feet. And this is what a lot of the strength coaches don’t realize—that these guys need speed. But what they are doing is constriction exercises. All this curling … you never do curls if you are boxing. Curling is a restriction. That is a pulling motion that constricts the biceps muscles.

“Everything in boxing is an extension, which is a pushing motion … not a pulling motion. If you are competing as an ‘Ultimate Fighter’ you can get your arm around a guy’s neck and choke him out. But you can’t do that in boxing. I never did any curls after I started fighting. I did them after I retired from boxing as part of my normal fitness routine, but not while I boxed.

“A lot of these strength trainers are body builders. They don’t know what it takes to be a boxer. If you are building yourself up using heavy weights your muscles are getting bigger and larger, but what you are doing is constricting and that will prevent you from extending your arm with suppleness and speed. Touch a bodybuilder’s arm—it’s hard like a rock. It’s not an athletic muscle.

“When I was training as a weightlifter I injured every part of my body. Lifting heavy weights puts a great strain on your muscles. There is a saying in lifting, ‘If you don’t have time to warm up, you don’t have time to train.’ It was very important to warm up. Even when I was training as a fighter I would loosen up like I was lifting. I would loosen up for ten or fifteen minutes and stretch out. And after my workout I would stretch out again … warm up and warm down.

“I believe weight training has a place in boxing but you have to know what you are doing. If I was training a boxer and wanted to integrate weights into his program, I would start out with ten-pound dumbbells and light squats. I would show him a routine to build him up. But more than anything what you need in boxing is ability, determination, and training. Strength isn’t as important as ability, speed and conditioning. That’s how Ali beat Foreman and Liston. That was speed and ability beating strength.

“I was fortunate to have a great boxing teacher in Rollie Hackmer. Rollie taught me something that fighters and trainers today do not know how to do. He taught me how to bob and weave and how to utilize my strength in the ring.”

Terry Todd, Ph.D., is a well known authority on weight lifting and bodybuilding. He is the publisher of Iron Game History and is professor of kinesthesiology at the University of Texas in Austin. Terry Todd could, if he wished, easily join the ranks of boxing “strength trainers.” His reasons for not doing so are both admirable and informative.

Terry Todd: “I think I know why the world of boxing was slow to begin to do what everybody else seems now to be doing. In boxing’s case it’s partly because the sport existed as a sort of separate activity once it stopped being a college sport in the late 1950s.

“When intercollegiate amateur boxing ended you no longer had the almost daily interaction that coaches in other sports have with one another, in which their having lunch together, or they pass one another in the hall, and they’d talk shop. People who were separated from what I would call traditional academic sports science didn’t hear as much, or talk about it, and therefore were not influenced by their peers in the same way they would have been had they still been part of it. Of course boxing was very active outside of the university setting for many, many years. But I believe this is part of the reason why—and I’m sure it’s not the only reason—but I suspect that it must play some role in why boxing was slow to adopt weight training.

“I think what has happened is that some boxing trainers, or managers, are reading about all of these changes that athletes have arrived at, from Tiger Woods on down, and some of them have sought out a strength trainer to work with their boxer. But I would be suspicious that a strength coach coming from another sport might not know enough about boxing to know how to put the fighter on a training program that would end up giving him what he needed without giving him what he did not need, if you follow me. In other words, give him something that would make him not just stronger but more powerful. Stronger is immaterial in boxing. Power is everything.

“I know there are boxing trainers who believe weight training could slow the speed of the boxer’s punch, and I am not prepared to say that such a view would be nonsense. But to me, when we have so much evidence that weight training appears to have improved speed … I mean there is a lot of raw data that doesn’t have to do with high level athletes, just average people, showing that rather than making a person slower, or losing flexibility, it appears that there is a slight gain in flexibility and a slight gain in speed of movement.

“However, I do believe that when some of the body building techniques that are popular now are done in combination with drugs—and particularly with drugs—you can produce enough body mass in certain parts of the body that it can actually lead to binding yourself in the way that historically people have argued you would become ‘muscle bound.’ I wouldn’t be surprised if some of what you see in boxing today, with the increased body mass and muscularity among certain fighters, is probably driven by steroids as well as by lifting.

“If a strength coach was able to increase the boxer’s explosive power and do it without adding enough body weight that would diminish his ability to throw more punches in any given round, or in the overall fight, and would not in any way cause him problems in terms of the defensive aspects of fighting, then you would come out ahead of the game. But in attempting to do this it would not be hard to put a boxer on a program—and I could write one out very quickly—that would be hurtful instead of helpful. I could easily give a boxer a weight-training program that has worked for other athletes. But I do not think it would be good for him.

“If someone said to me, ‘Well, I don’t care if you have qualms about this, you’re the guy, and we want you to give us your best thinking about strength training for our fighter,’ I would have some theories and ideas to suggest, but the only thing I’d feel pretty confident in was putting a boxer on a program that would not be really ideal for him and perhaps do more harm than good. What I would end up suggesting would only be by inference in that I would give him what has been demonstrated to be helpful for baseball players, tennis players or wrestlers. I know they are not the same sport but we do have a good bit of experience with these individuals.

“It could be that in time, as they begin to understand the special needs of boxers, the strength coaches will stay away from the type of resistance training that would not be helpful, and might even be harmful, and focus on where there could be benefits. What you don’t want to do is give up on any of boxing’s traditional training methods that have proven to work in the past and continue to be effective.

“One of the things that always interested me about boxing was how the athletes used to train with the medicine ball. I know that type of training fell out of favor in all sports but it was very popular years ago, along with light dumbbell exercises, and lots of sportsmen, even non-boxers, did it. The medicine ball workout built up the rotary muscles of the trunk and toughened up the midsection for being hit. For a while it just fell out of favor, especially with the people who were training athletes with weights, but I’ve noticed lately that it has gotten popular again.”

The saying “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it” should apply to boxing. Traditional boxing trainers—the few that are left—are not closed-minded. They are open to new ideas, provided they work. Unfortunately, most of the people currently training and managing boxers have no idea what’s broken and what isn’t.

Resistance training utilizing moderate to heavy weights has proven useful to athletes in football, track and field, baseball, wrestling and golf. However, when applied to boxing this type of training has not proven its worth and is, in fact, detrimental to the boxer. Hiring strength coaches who do not understand or have experience with the requirements and complexities involved in training professional fighters bears witness not to the sport’s improvement but to its continuing regression.