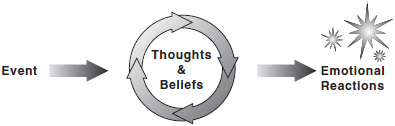

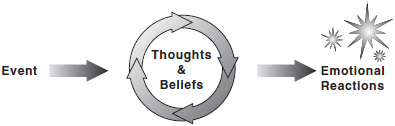

You probably think an event itself determines the way you react to it. That is not true. Actually, your beliefs and thoughts determine how you react. This is why two people can react so differently to the same event. Understanding the relationship between thoughts and reactions is critical to learning to control stress. To illustrate, let’s look at an example.

Imagine yourself standing outside a movie theater where a friend has agreed to meet you for the 6 o’clock show. You arrive on time at 5:45, and you stand outside the theater. Try to picture the scene—traffic going by, people walking past laughing and talking, the temperature of the air, and the sounds and smells around you. Imagine yourself pacing slowly up and down, looking at the advertisements, watching other people go in. It’s now 5:50, then 5:55, and still there is no sign of your friend. Finally, the clock strikes 6. The last people have gone in, the movie has probably already started, and still your friend is not there. Stop and ask yourself how you would feel . What would your actual emotion be, and how strong would it be on the 0–8 scale? Most people report that they would be either worried or angry (maybe around a 6 on the scale).

Now imagine that your friend comes running around the corner and, before you can say anything, says, “I’m so sorry I’m late, but there was an accident right in front of me and I had to help the people while they were waiting for the police and ambulance and my phone has died.” Now how would you feel? At this point, most people report that their anger or worry disappears.

If we asked you what caused your emotions as you stood outside the theater, you would most likely answer that you were worried or angry because your friend was late. But let’s look at what happened. Obviously, your friend was late before she showed up. But she was still late even after she arrived. In other words, the event did not change; your friend was late in both cases. However, your emotion changed dramatically. So it could not have been the event that directly caused your emotion. What changed was your interpretation of the event—your beliefs about it. These beliefs are what caused your emotion.

Before your friend showed up, you might have been thinking such thoughts as, “She’s always late” or “She’s so irresponsible.” Those thoughts would have made you feel angry. If you were thinking, “I hope she’s okay” or “Maybe she had an accident,” or perhaps “Did I come at the wrong time?” you probably would have felt anxious. After your friend arrived and you realized that she was neither hurt nor irresponsible, your thoughts immediately changed. In other words, it was your beliefs about your friend’s lateness—not the lateness itself—that caused you to feel worried or angry. If you could have changed your beliefs while you were waiting, you could have saved yourself a lot of unnecessary stress. That is exactly what you will be learning to do in this lesson and the next.

In order to think realistically, you should understand these five points:

• Your emotional reactions are the direct result of your thoughts and beliefs about an event, not the results of the event itself. Two people react differently to the same event because they think differently about it. Let’s say that two men go up in a plane for a skydiving lesson. One man happily jumps out of the plane because he thinks he will experience a great feeling of freedom. The other decides to stay inside the plane because he thinks he might get killed. The relationship between events and reactions is shown below:

• Extreme emotions are caused by extreme beliefs. By changing your extreme beliefs, you can learn to control your emotional reactions.

• Many of your thoughts and beliefs are automatic, which means that they come very fast and you may not be consciously aware of them. So, it may seem that you just react, without any thought. But the thoughts are really there. It just takes time and practice to identify them.

• Although it is not easy, it is possible to learn to control your thoughts and thus control your emotional reactions. Most people who are troubled by stress believe they have no control over their reactions. But, as we have stated, this simply is not true. Your thoughts and beliefs are not easy to change; you have spent many years developing them, and they have become a part of you. But you can change them. Once again, the key is practice.

• Realistic thinking is not the same as positive thinking. Positive thinking asks you to look through rose-colored glasses and see the world as a wonderful place. But we all know the world is not always wonderful; this is why positive thinking never lasts long—we tend not to believe it. Realistic thinking, in contrast, asks you to look at situations rationally and objectively. This means that sometimes it is reasonable to feel anxious, angry, or sad. Other times you will notice that your emotions are linked to unrealistic thoughts. When this is the case, the key to changing your emotions is to believe your new thoughts.

People who are highly stressed tend to make two types of errors in thinking. First, they overestimate how likely it is that an unpleasant event will happen (overestimating the probability). Second, they overestimate how bad the consequences will be if that event does happen (overestimating consequences). In this chapter we will examine the first of these errors: overestimating probabilities. We will discuss the second in the next chapter.

No doubt you can think of times in your own life when you have overestimated the probability of something bad happening. For example, if your boss says he wants to talk with you, you may immediately think, “He’s going to yell at me.” If someone cuts in front of you in traffic, you may think, “She did that intentionally.” Or if you are asked to take on a new responsibility, you may think, “I won’t be able to do it.”

In each of these examples, you are assuming a 100 percent probability. By thinking that your boss is definitely (100 percent) going to yell at you, you are thinking that there is no other reason your boss might want to talk with you. Realistically though, there are many reasons your boss may want to talk with you, only one of which involves anger. So you are overestimating.

You may be overestimating even if you don’t assume that an unpleasant event is definitely going to happen (100 percent probability). For example, you may not think that you definitely can’t do the job, but you may still think that it is very probable that you can’t, say 70 percent. But if you have been asked to take on a new responsibility, then at least someone thinks that you can do it.

Overestimating probability does not apply only to worrying. It can also apply to other negative emotions such as depression or anger. If your neighbor is playing his stereo loudly, you may think, “He’s just doing this to annoy me.” Actually, however, the realistic probability that annoying you is your neighbor’s motive is much less than 100 percent and is probably quite unlikely. Imagine if instead of that belief, you thought to yourself, “He may be doing it on purpose (say 5%), but it’s more likely he doesn’t realize it’s bothering me.” Think about how much less angry you would be. If you can learn to estimate and think about probabilities more realistically, you can reduce your stress.

To change the way you think, you must first learn to identify your thoughts. You can do this by asking yourself questions. Each time you notice your stress level increasing, ask yourself, “What’s making me feel this way?” or “What is the bad thing I’m expecting here?” Let’s say a business meeting has just been scheduled for this afternoon, and you are worried about it. Immediately ask yourself, “Why am I worried?” If you answer, “Because there is a meeting,” remind yourself that events do not cause feelings. Ask a more specific question: “What is it about this meeting that is making me worried—what bad thing am I expecting?” You may answer something like, “I might have to present a report.” Now you have managed to identify a belief or, put another way, a negative expectation.

It is important that you be totally honest when you are trying to identify your thoughts and beliefs. Sometimes when you ask yourself a question, the answer may seem so silly that you will not want to admit that you actually had such a thought. But much of our stress is caused by silly beliefs—and they stay with us precisely because we never spell them out and realize how silly they are. So having ridiculous thoughts does not mean that you are crazy. Denying that you have them can hurt more than acknowledging them.

Of course, not all your thoughts will be easy to identify. If you feel an emotion and cannot determine what is behind it, try to guess a few likely thoughts. The simple process of considering and rejecting these possibilities may lessen your stress, or may lead you to the thought that is really causing your emotion.

For example, let’s imagine that you came out of a shop to find that someone has double-parked beside you and you cannot move your car. You feel an immediate rush of intense anger. To do realistic thinking means that the first step would be to ask yourself, “Why am I feeling angry?” If you cannot come up with an answer, try and make up a few possibilities: “This person is deliberately trying to make me late,” “I am extremely inconvenienced,” “This person is trying to take advantage of me in some way.” By brainstorming in this way, you might find that one of these thoughts rings a bell and is the main underlying belief that you have in the situation. Even if none of the thoughts rings true, questioning the reality of each one (see below—Looking at Evidence) should help to reduce your anger.

There are two other rules to remember when identifying your beliefs. First, you should try and phrase your belief in the form of a statement. Statements of supposed “fact” are usually responsible for negative feelings, but we often don’t realize this. For example, if your house was broken into and you thought to yourself, “I wonder if I’ve lost a lot?” (a question), you would probably not be too depressed—instead you might be concerned, inquisitive, or curious. These are not emotions that are too stressful. However, if you were to think, “I’ve lost everything,” then you would probably be feeling very depressed or panicky. In other words, extreme, negative feelings generally follow statements of negative events. If you find yourself identifying a curious question as your thought or belief, then you have probably not identified the real thought—in other words, the negative expectation.

Second, for this exercise, you should also try not to let feelings or voluntary actions be the subject of your thoughts. For example, you might ask yourself the question, “Why am I feeling nervous about this meeting?” and might then identify the thought, “Because I will be embarrassed.” But remember, embarrassment is not a necessary outcome to the meeting. It will depend on how well you can do your realistic thinking. So looking at how realistic this belief might be is not possible because it will depend on you. Instead, you should ask yourself, “What is it about the meeting that might make me feel embarrassed?” If you then come up with a statement such as, “I haven’t prepared my work properly,” then this is a clear statement and belief that you can check in terms of how realistic it is. Similarly, if you come up with a thought regarding why you are feeling anxious about the meeting along the lines of, “Because I’m sure I’m not going to say anything,” then again this cannot be tested because it is up to you whether you say anything or not. A thought such as “I know I’ll say something stupid,” on the other hand, can be checked for reality.

Once you have identified your initial thought, the next step is to ask yourself, “How likely do I really think it is that this will happen?” Usually, the lower the realistic probability, the less intense your emotion will be. For example, if your partner is late and your initial thought is that he or she has had an accident, you will be far more worried if you think there is a 50 percent chance of an accident than if you think there is only a 5 percent chance.

The goal is to convince yourself that the probability of a negative outcome is as low as possible. But you must really believe it. If you tell yourself that there is no chance your partner has had an accident, even though you believe deep down that there is a good chance, you will not reduce your level of stress. The key is to change your actual beliefs, not simply to change what you say to yourself. To help to really convince you that you are overestimating, you need to learn to look at realistic evidence for your beliefs. By learning to always check your thoughts against the evidence, you can start to think much more realistically. There are four types of evidence that will help you.

The first way for you to identify real evidence about a belief is to consider all of the facts, figures, and general rules about a situation. For example, what have other people told you about this situation, what have you read, or what have you heard through the media? One warning—everyone thinks they know the difference between real evidence and wild imaginings. But people who are highly stressed tend to ignore the positive evidence and focus only on the negative. You need to look out for this tendency in yourself. Try consciously to focus on all of the evidence, not only on the negative.

Say your partner is late and you are trying to determine the realistic probability that he or she has been involved in an accident. You may ask yourself, “How many cars are on the road in the city tonight?” Perhaps you estimate 10,000 cars. Then, based on your rough knowledge of accident rates, you may ask yourself, “How many of those cars are likely to have an accident tonight?” Perhaps two. That means there is a 2 in 10,000 chance that your partner will have an accident—no doubt much lower than you originally thought.

You might have a tendency to say, “Yes, but I always think that my partner will be one of the two.” This is precisely what we mean when we say that your thinking needs to stop being based on “gut feeling” and to begin to be based on realistic evidence. You need to look at all of the evidence and realize that your partner has about the same chance of being in a car accident at any given time as you have of winning the lottery!

Another good way for you to challenge your estimates is to try and look at previous experiences you have had in that situation. For example, with your partner who is late getting home, you might ask yourself, “How many times in the past has my partner been home late?” “How many of those times were because of an accident?” “Is my partner generally a good driver?” “Would I have heard by now if he or she had been in an accident?” Your answers to these questions will probably help you to further reduce your estimate of how likely it is that your partner has been in an accident.

Remember again not to focus on the negative. Maybe your partner did have an accident once and came home late. But what about the 50 times he or she has been late for other reasons? If you focus on the one time and ignore the 50, you are not thinking realistically. Chances are, once you have examined all the evidence, your initial thought will not seem nearly as likely as it did at first.

Another way to learn to think more realistically is to think of all the possibilities, not just the one that initially worries you. For example, why, apart from an accident, might your partner be late? List the possibilities: he or she got caught in traffic, had a flat tire, met some friends, or maybe had to finish a project at work. You know your partner’s habits. Does he or she oft en lose track of time? Does he or she like to work late because the office is quiet after others go home? Clearly, an accident is only one of a large number of possible reasons for your partner’s lateness. There is little use in focusing on one negative possibility if so many other events are equally possible.

By examining the realistic evidence and listing all the possibilities, you should be able to convince yourself that, while your partner may have had an accident, the probability is actually very, very low. If you really come to believe this (by convincing yourself with evidence), your stress will decrease.

Finally, a good way of looking at realistic probabilities is to try and see the situation from a different perspective—usually, someone else’s. For example, if the situation were reversed and you were the one who was late coming home, would you expect your partner to be stressed? Why not? The answer to this question will often help you to see how unrealistic you are being and will help to change your view of the situation.

Changing perspectives in this way is a good strategy for finding evidence relating to social situations. These situations are oft en difficult to examine in other ways. There are usually no statistics or written facts about social situations. For example, imagine that two colleagues are talking loudly outside your office. You may feel angry and identify a thought such as, “They are totally inconsiderate.” Now try to change perspectives—imagine that you are one of the people talking in the corridor and one of the colleagues is in his office. Are you talking loudly because you are totally inconsiderate, or could there be something else going on—perhaps you don’t realize how loud you are? By putting yourself in the other person’s place in this way, you can often reduce your extreme feelings very quickly.

No one said it would be easy to change your thoughts. It is not enough to read through this lesson and say, “Okay, I’ll think more realistically in the future.” Your negative thoughts are deeply ingrained in you; they come automatically before you can stop them. If you want to replace them with realistic thoughts, you will have to make a commitment to regular, formal practice. The way to do this is to write down your thoughts and then challenge each one. To challenge a thought means to look at all of the evidence for it and then decide how realistic it is based on that evidence. Writing out your beliefs may seem tedious at first, but it is the best way to identify and examine them objectively.

The form to use for this step is the Realistic Thinking Record, a form for recording your thoughts and your responses to them. This form is a bit trickier than the others you have used, and it is important that you use it correctly. If you read the instructions below carefully and consider the examples and case studies that follow, you will soon be an expert at using the form.

• In the first column, record the event—the thing that triggered your negative feelings. Include only the event, not your feelings about it. For example, in this column you would put “job interview tomorrow,” not “doing badly at the job interview.”

• Next, record your initial expectation, thought, or belief. Ask yourself, “What is it about this event that bothers me?” This then is the belief that is directly leading to your negative feeling. Remember to be totally honest about identifying this belief, even if it sounds silly. Remember, also, to phrase this belief in the form of a statement and to try not to include feelings or actions that are up to you.

• The most important column is the evidence. Here you need to list all of the evidence you can think of that supports or does not support your belief. Because this is realistic thinking (and not positive thinking), you do need to record even evidence that supports your belief. Hopefully, if you are being honest and are thinking hard, you will find more evidence against your belief than for it. However, when you do this exercise, you might occasionally find that your beliefs are realistic. In this case, the exercise might be telling you that it is quite understandable to feel stressed about this situation and perhaps you need to deal with it in a different way, such as trying to change the situation.

When you are listing the evidence, try to think of each of the four types of evidence we discussed—general knowledge, past experience, alternative explanations, and changing perspectives. Not all types of evidence will fit for all situations, and you may need to be clever and think up other types for some situations. Remember to watch out for biases in your thinking. Make sure you look at all of the evidence, not just the negative.

• Once you have carefully evaluated all of the evidence for your belief, you should record the realistic probability that the outcome you are thinking about will occur. Take what you have written in the second column and ask, “Realistically, how likely is it that it will happen?” We hope that if you take into account all of the evidence, this probability will not be as high as it was when you began the exercise.

• Now that you have determined the realistic probability, how intense is your emotion about the event? Record that number in the last column using the 0–8 scale that you should now be familiar with. Ideally, having determined the realistic probability should make the intensity lower than it was when you began the exercise. But, remember, your emotion will only change if you believe your new probability. If you are simply saying a low probability to yourself, but believe deep down a higher probability, your emotion will stay high.

If you do not find your emotion changing, don’t despair. This is not an easy technique, and it will take lots of practice. It will not start to work overnight. We will also learn lessons in later weeks that will help the realistic thinking to work, and we will also continue on to the second part of realistic thinking in the next lesson. So, at this stage, your aim should be to practice the realistic thinking technique, not necessarily expect it to work completely. We hope you will start to see some effects from it, but there will be later additions that will help.

The Realistic Thinking Record is designed to be filled out each time you notice yourself reacting emotionally to an event. Make lots of copies of the record and carry it with you. When you feel your stress rising, fill out the form immediately if you can. If you can’t, do it as soon as possible— no later than the end of the day. Write down your thoughts and examine the evidence for each one. You should not wait for major stresses to use the technique. Remember, at this stage your main aim is to practice. Therefore, you should grab the opportunity to use the form whenever you notice any degree of stress, no matter how small.

Your ultimate goal is to reach a stage where you automatically interpret events realistically, rather than automatically seeing them in a negative way. In other words, you will eventually be able to do your realistic thinking while the event is happening. At first, however, most people stumble through a stressful event any way they can, then sit down later to try to think more realistically about it. This will not reduce your stress during the day, but it does give you practice. Next time, you will be able to start your realistic thinking a little sooner.

If, like most of us, you have some continuing worries or aggravations—money, your children’s health, job pressures, an annoying work colleague—practice realistic thinking on those as well. Long-term stresses provide a good chance to try to change your thinking during the event—in other words, while you are stressed, instead of later.

Anne wanted her daughter Ellie to start preparing some of the evening meals. But when she thought about approaching Ellie with this request, she felt very anxious (6 on the 0–8 scale). The first step was to try to identify her negative expectation. To do this she asked herself, “What is it about asking Ellie that worries me?” Her answer (her initial expectation) was that Ellie would get angry. Anne realized that she was assuming there was a strong chance that Ellie would get angry, and as soon as she recognized that thought she knew she was overestimating.

Anne then considered the evidence for her initial expectation. She considered her previous experiences and recalled a time when she’d asked Ellie to clean the bathroom. Ellie didn’t look exactly overjoyed, but she wasn’t angry. Anne told herself, “It’s a reasonable request that she help out,” and “Most adults who live in the same house share the chores.” Next, she looked at alternatives, at how Ellie might respond. “Maybe she’ll be happy to help,” thought Anne. “Or maybe she won’t be happy but still agree that it’s a fair request.” Finally, Anne tried to reverse positions and imagine what she would say if she were the one being asked to help out more at home. Anne knew straightaway that she would see what a fair request it was, and try her best to fulfill it.

Anne realized that her estimated probability of Ellie being angry (80 percent) was much too high. She decided that the realistic probability was more likely 20 percent. This new way of looking at the situation helped her stress level decrease, from a 6 to a 3. You can see that Anne was being realistic: she still thought there was a reasonable chance that Ellie would get angry, and so she still felt a little nervous. But she managed to reduce her estimate from 80 percent to 20 percent, and this helped her to go from feeling really scared to a little nervous. Below is Anne’s Realistic Thinking Record for her work situation as well as other examples from her week.

Anne’s Realistic Thinking Record

Joe had been with his wife in a restaurant where the waitress had forgotten their order and kept them waiting for 30 minutes before Joe finally asked what was happening. Joe had blown up at the time and had then spent the rest of the evening in a bad mood. Although he did not do his realistic thinking at the time, Joe’s wife encouraged him to do it that night, as a practice. When Joe asked himself what it was about his order being forgotten that triggered his anger, he identified his main initial belief as, “The waitress is incompetent.” Joe then tried to examine the evidence that the waitress was incompetent just because she forgot the order. His main evidence was found when he looked at alternative explanations for the order being forgotten. Joe realized that maybe the waitress had been extremely busy, maybe some major event had happened to distract her, or maybe some major issues in her life had made her particularly distracted tonight. He also changed positions with the waitress mentally and realized that, if it had happened the other way around, he would expect a customer to accept a single mistake and that one mistake does not mean a person is generally incompetent. Weighing up this evidence, Joe realized that there was a slight to moderate chance that the waitress was incompetent, but it was not 100 percent as he had originally felt. Below is Joe’s Realistic Thinking Record.

Joe’s Realistic Thinking Record

![]() Practice recording your thoughts and estimating realistic probabilities for at least one week on the Realistic Thinking Record.

Practice recording your thoughts and estimating realistic probabilities for at least one week on the Realistic Thinking Record.

![]() Record your thoughts and probabilities as soon as you notice your stress level increasing.

Record your thoughts and probabilities as soon as you notice your stress level increasing.

![]() At the end of the day, think of any instances in which you overreacted to an event but did not have a chance to record it. Record your thoughts and challenge them as if they were happening right now.

At the end of the day, think of any instances in which you overreacted to an event but did not have a chance to record it. Record your thoughts and challenge them as if they were happening right now.

![]() Continue to fill in your

Continue to fill in your

![]() Relaxation Practice Record

Relaxation Practice Record

![]() Daily Stress Record

Daily Stress Record

![]() Progress Chart

Progress Chart

![]() You can move on to Step 4 in about a week if you feel that you are getting the hang of realistic thinking. If you feel unsure in any way, reread this chapter and keep practicing for a little longer.

You can move on to Step 4 in about a week if you feel that you are getting the hang of realistic thinking. If you feel unsure in any way, reread this chapter and keep practicing for a little longer.

In this lesson we learned that your emotional reactions are directly related to your thoughts and beliefs about an event, and are not a direct consequence of the event.

• People who are stressed have a tendency to overestimate the probability of negatives in a situation.

• Realistic thinking is a method of changing your beliefs about a situation or event by looking at all of the evidence.

• Realistic thinking allows for the possibility that your thoughts may be realistic and, therefore, that your emotions may be appropriate in some situations. This is different from positive thinking, which is often hard to believe.

• Four main types of evidence can help you to determine whether your expectations or beliefs about a situation are realistic:

• General knowledge

• Past experience

• Alternative explanations

• Changing perspectives