One of the key features of stress is that it grabs your attention and focuses it on the source of threat. As discussed in Step 1, this is a helpful process if you are in immediate physical danger. However, if you are not in immediate physical danger, the tendency to focus on perceived threat is not beneficial—it just makes you more stressed. Often, when people are stressed, they are focused on things that might happen in the future (for example, not getting work in on time, being late, being disapproved of, or being embarrassed). If you look over your Realistic Thinking Records, you will probably see lots of these future-focused thoughts.

Sometimes stressful thoughts might not be concerned with the future, but rather focused on the past. It may be that you experience significant stress when thinking about events that have already occurred. This may be because you think the event shouldn’t have happened, and you blame yourself or someone else. Perhaps you rehash the event over and over in your mind, thinking about how you could have handled it differently. Or it may be that you are worried about the consequences of the event, taking you once again to future-focused thoughts.

Either way, we know that chronically stressed people are often absorbed in either the future or the past. Realistic thinking is a technique to ensure that your thoughts about the future or past are realistic, both in terms of probability and consequences. However, some people also find it useful to simply change the focus of their attention. Rather than focusing on the future or the past, they choose to focus their attention on the present moment, that is, what is actually happening around them right then and there.

You have already had some experience with present-focused attention in two of the earlier steps in this program. The first experience would have been in Step 2, when you learned deep muscle relaxation. Remember, the “break” minute between muscle groups, when you focus on your breathing? This develops your ability to stay focused on the present moment and to let all other thoughts and distractions go. You may find this part of relaxation to be a challenge. If so, don’t be concerned—in this step we introduce a technique for making it a little easier.

Your second experience of present-focused attention would have occurred in Step 5—prediction testing. When testing predictions you usually need to focus on what is actually going on around you, in order to gather the evidence you require. So, even though it is different from relaxation, prediction testing also involves present-focused attention. If you are carried away with thoughts about the future or the past, you will not be able to test your predictions accurately.

In this chapter, we build on these earlier experiences of present-focused attention, and introduce a new technique that you can use in almost all stressful situations. You may have heard of the concept of mindfulness. Mindfulness meditation is an awareness practice that derives from Buddhism. One of the defining features of mindfulness meditation is that it involves present-focused attention. Western psychologists have taken the concept of mindfulness and adapted it for treating stress, anxiety, and depression, with good results. Mindfulness meditation has also been found to have significant benefits for people with physical health problems such as chronic pain and coronary heart disease.

Many books have been written on mindfulness meditation, and it is not within the scope of this book to address it in depth. However, we will present some simple tips, taken from mindfulness, to help you stay in the present moment.

1. Start by focusing on your breathing, just like in your relaxation exercise. Breathe slowly and evenly. Notice the rise and fall of your chest and stomach as you inhale and exhale.

2. Now use your five senses. Ask yourself, “What can I see, hear, smell, feel, and taste—right now?” Notice the details. Pretend you are describing it to someone who has never seen, heard, smelled, felt, or tasted it before.

3. Notice when thoughts distract you. These thoughts might be the typical worries you oft en experience. Or they might be thoughts about the exercise itself, such as “Am I doing this right?” or “This is silly.”

4. Let those thoughts go. Make a decision not to engage with them right now. You can think about them later if they are important.

5. Refocus your attention. Return your attention to your breathing, and then use your five senses again. You may need to refocus many times as your mind wanders—don’t be distressed by this. Refocusing once your mind has wandered is a key part of the process.

Two of our case studies, Joe and Anne, found staying present to be a particularly useful skill. The following descriptions show how they put it into practice.

Joe noticed that he often felt highly stressed on the drive to work. He had completed a Realistic Thinking Record and knew that he spent much of the drive thinking about how bad the traffic was, predicting that he would be late for work, and worrying about all the work he had to get done. Joe knew that many of his predictions were unrealistic and unhelpful. For example, he knew that he was usually not late for work, and that even if he was late it wouldn’t matter very much. He also knew that the traffic was outside his control, and that no amount of stress and agitation on his part would make it move any faster.

Despite this realistic thinking, Joe still found the drive to work a stressful experience. He decided to practice staying present during the journey, hoping that this would help. In order to steady himself, Joe began by focusing on his breathing. He took slow and steady breaths, focusing on the rise and fall of his chest as the air flowed in and out. Next, Joe used his five senses to keep him fixed in the present moment. For example, he noticed that the clouds outside were dark gray in the center, with fluffy white edges. He became aware of each vehicle around him and his position on the road. Joe paid attention to music on his stereo and identified the separate sounds of the guitar, drums, and keyboard. He noticed the faint taste of toothpaste in his mouth.

Joe noticed the feel of the steering wheel in his hands and became aware that he was gripping it tightly. He used his relaxation training to let the tension go, and noticed the impact of this on his hands, arms, and shoulders. He became aware of several odors in the car—gasoline, coffee, soap.

As he was practicing being in the present moment, Joe also noticed some of the same old worries creeping back into his mind. At first Joe found these distracting. It was hard not to get carried away with his usual worrying thoughts. It took him some effort to let them go and refocus on the present, which he did by returning his attention to his breath. Once again, Joe used his five senses to anchor him into the present moment. He repeated this process time and time again, returning to his breath every time he noticed a distracting thought.

By the time he arrived at work, Joe felt considerably less stressed than usual. He was also reminded of how much he enjoyed music when he really listened, and resolved to dig out some of his old CDs after work.

Anne had taken a useful step toward reducing her stress by committing to a half-hour walk after work most evenings. However, she was disappointed to find that it didn’t help as much as she’d hoped. Anne usually walked with a sense of urgency, keen to get the walk over with so she could get on with other things at home. Anne’s Realistic Thinking Record revealed frequent thoughts such as “This is a waste of time,” “This isn’t helping,” and “I really should be doing X.” Often she felt even more tired and irritable by the time her walk was over.

Rather than giving up, as she was tempted to do, Anne decided to practice staying present during her walks. Instead of judging whether the walk was worthwhile or not, Anne focused her attention on her breathing, and what was actually around her. She really noticed the colors in the sunset, the salty smell of the nearby lake, and the crunch of leaves underfoot. As soon as she became aware of the usual worries about home and work, Anne reminded herself of her wish to stay present, just for this half hour. She then returned her attention to her breath and used her five senses again. Anne focused on what she could see (yellow and orange leaves, the muddy path, her own feet), hear (birdsong, a dog barking, the shouts of a child), feel (a breeze against her cheek, the soft lining of her coat pockets in her hands), smell (a fire burning, salt, her own perfume), and taste (apple). For the first time, Anne actually enjoyed her walk.

As you can see, both Joe and Anne used their breath and their five senses to anchor them into the present moment. This didn’t mean that their usual worries didn’t intrude—of course they did. But Joe and Anne patiently kept returning to their five senses time and time again, resulting in a significant reduction in their stress.

One analogy that can be useful is to think of your mind as a distractible puppy you are taking for a walk. You want the puppy (your mind) to stay on the straight and narrow path of the present moment. The puppy, however, wants to head off in all different directions, sniffing a future tree here and a past bush there. There is no point getting upset with the puppy, as it is just behaving as all puppies do. Instead, it is your job to notice when the puppy is heading off course, and gently tug it back onto the present path. If you remain patient, and keep doing this time and time again, the puppy will soon be spending more time in the place you want it to be.

What? There’s magic in worry? Not really, but plenty of people seem to think there is. When you worry, all the possible outcomes to a situation swirl around and around in your mind. Oft en the thoughts keep swirling even when you know there is nothing you can do to change the situation you are worrying about. It’s almost as if you believe that worrying will magically change the outcome. That is the so-called magic of worry. In other words, some people almost seem to believe that they must worry over things, just in case there is something that they have missed or forgotten.

This belief probably comes from the human need for control. Most of us have trouble accepting the idea that there are some things in life that we just cannot control. Rather than accepting this reality, we keep worrying, unconsciously hoping that somehow the worry will change things. This belief may not be conscious, but the worry is. Breaking the worry cycle requires you to accept the fact that you cannot control everything. Some events are going to happen whether you want them to or not, whether you worry about them or not. Your worrying will have absolutely no effect on these events. But it does have an effect on you; it can make your life very unpleasant.

Our case study Anne illustrates this principle well. Anne often worried about her daughter when her daughter stayed out late at night. She knew that her daughter was a grown, capable woman and that it was unlikely anything terrible would happen. But she felt that, by worrying about her daughter, she could reduce the chances of a negative event. Anne described a “magical” belief about the power of her own thoughts: “If I worry about it, it won’t happen.” This belief got in the way of Anne’s efforts to stay in the present. On the one hand, she wanted to worry less, but, on the other hand, worry made her feel safe. So naturally it was hard for Anne to let these worries go.

It was only when we questioned this “magical” aspect of worry that Anne was able to recognize how unrealistic, and unhelpful, her beliefs about the worry process were. Logically, she could see that worrying would have no impact whatsoever on the potential events that could befall her daughter. Some people would drive dangerously, whether Anne worried about it or not. Others would commit crimes, regardless of what Anne thought about as she lay in bed at night. It was hard to accept, but Anne had to realize that she could not protect her daughter from all the bad things in the world.

Anne eventually accepted that she did not have control over what happened to her daughter. But she realized that she did have control over her own thoughts, and her own stress. Anne decided to focus on the life that was taking place all around her, not the imaginary life in her mind. Once she made this decision, it was much easier for her to use her breath and five senses to stay in the present moment.

It may sound simplistic just to tell yourself, “Don’t worry.” But worrying is like any other habit; the first step toward breaking it is becoming more aware of it. When you are aware that you are worrying, you can make a conscious decision to return your attention to the present moment. If you need reinforcement, try putting up signs. For example, you may want to make yourself a large sign that says, “Return to the present!” and tape it to your refrigerator to remind you. Or put a reminder in your phone for times that you know you are most likely to worry.

Like all the other techniques outlined in this book, staying present is a skill that takes practice. But don’t be concerned. Practicing this skill won’t take any extra time out of your day! Staying present can be practiced while you are going about your usual business. For example, you could practice staying present while driving to work or taking a walk, as in the case studies above. Or you could practice while doing everyday chores, such as doing the laundry, brushing your teeth, or watering the garden. Use your imagination. There is no end to the activities during which you could practice this skill!

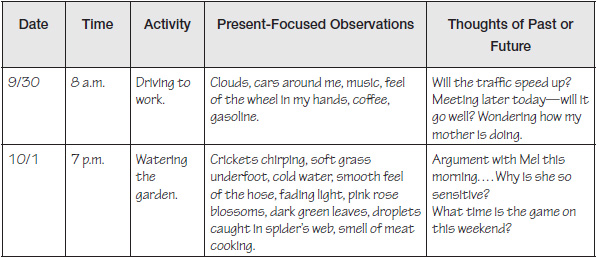

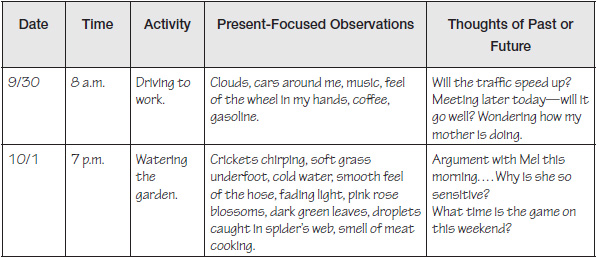

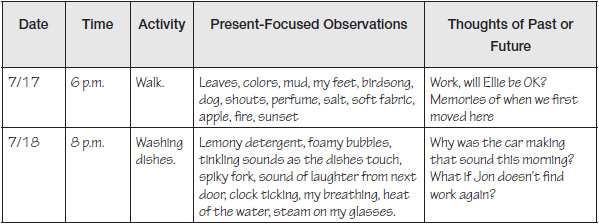

To help you practice, use the Staying Present Record. Complete this form after each practice.

In the first two columns, record the date and time you practice. This will allow you to see how regularly you are practicing.

In the next column, record the activity you are doing as you practice.

Next, write down any present-focused observations you made. That is, anything you noticed with your five senses. You probably won’t be able to note down every small detail that you noticed, but that’s OK. Just note down the ones you easily remember.

Finally, write down any thoughts of the present or past that you noticed while you were practicing. Remember not to worry if you have these thoughts while you are trying to stay present. Just notice them and return your attention to what is around you, using your five senses.

Joe’s Staying Present Record

Anne’s Staying Present Record

![]() The steps for staying present are:

The steps for staying present are:

1. Start by focusing on your breathing. Breathe slowly and evenly. Notice the rise and fall of your chest and stomach as you inhale and exhale.

2. Now use your five senses. Ask yourself, “What can I see, hear, smell, feel, and taste— right now?” Notice the details. Pretend you are describing it to someone who has never seen, heard, smelled, felt, or tasted it before.

3. Notice when thoughts distract you. These thoughts might be the typical worries you often experience. Or they might be thoughts about the exercise itself, such as “Am I doing this right?” or “This is silly.”

4. Let those thoughts go. Make a decision not to engage with them right now. You can think about them later if they are important.

5. Refocus your attention. Return your attention to your breathing, and then use your five senses again. You may need to refocus many times as your mind wanders—don’t be distressed by this. Refocusing once your mind has wandered is a key part of the process.

![]() Remember that staying present takes persistence. It is normal to be distracted by thoughts and worries. The key is to notice when your mind has wandered and use your breath and five senses to return to the present, time and time again.

Remember that staying present takes persistence. It is normal to be distracted by thoughts and worries. The key is to notice when your mind has wandered and use your breath and five senses to return to the present, time and time again.

![]() Keep filling in your

Keep filling in your

![]() Daily Stress Record

Daily Stress Record

![]() Progress Chart

Progress Chart

![]() Prediction Testing Record

Prediction Testing Record

In this lesson we introduced a technique for staying present.

People who are stressed often spend much of their time thinking about possible threats in the future or the past. By focusing on the present moment, that is, what is actually happening around you right now, you can reduce your stress.