CHAPTER 5

Dropping into Darkness

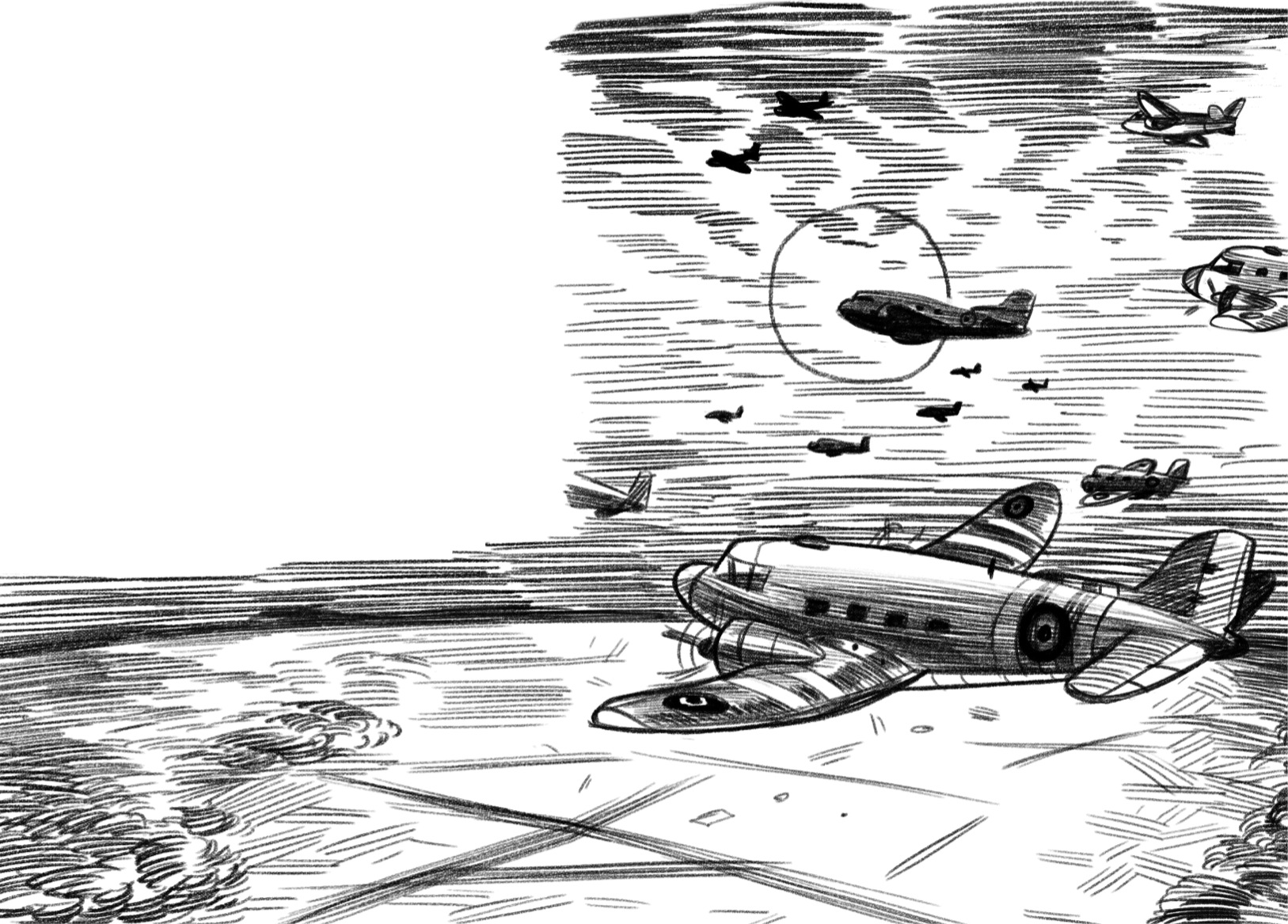

Just after midnight on June 6, 1944, the largest air fleet in history began winging its way across the English Channel. More than eight hundred planes lifted off from air bases scattered around England. In the air, the planes formed perfect long lines. About 20,000 paratroopers were on board. They were going to parachute into enemy territory in the dark!

Usually the paratroopers joked around with one another. Many had become good friends after training hard together for nearly two years. But that night, “the men sat quietly, deep in their own thoughts,” said General Matthew B. Ridgway.

No doubt, they were thinking ahead to their dangerous goal. They had to take control of the important bridges and roads that led away from the beaches. These routes were the only way the Allies could move big numbers of troops inland—and right now they were heavily guarded by Germans. The Allies had already destroyed other major bridges and roads, so these routes were key.

The airplanes neared Normandy about 1:30 a.m. Suddenly, planes started rocking wildly and veered off course. The air blazed with tracer bullets fired from German guns on the ground. Blue, green, and yellow streaks lit up the sky like fireworks.

Soldiers lurched inside as their planes took hits. The shells sounded “like someone threw a keg of nails against the side of the airplane,” said Sergeant Dan Furlong.

Airplanes turned into death traps. Pilots opened hatch doors and flashed the green light—the signal for paratroopers to jump. According to the plan, it was much too soon. The locations where they were supposed to land were still far away! And yet it was safer to jump than to stay aboard the aircraft. “The green light popped on and, ‘Go Geronimo,’ we all jumped,” said trooper Carl Cartledge. “I’ve never been so glad to get out of an airplane in my life!”

Chaos filled the sky. Thousands of planes were swerving off course, trying not to collide. Enemy machine fire caught troopers in the air. Burning aircraft exploded and plunged to earth. Troopers landed all over—in fields, trees, and barns. Hardly any ended up at the correct spots.

Some troopers hit the ground at high speeds. They stayed black-and-blue for days. Landing in water was even worse. Paratroopers plunged into fields that the Germans had flooded in order to block the advance of Allied troops. Fighting for their lives, soldiers struggled to break free from heavy gear and tangled chutes. Hundreds drowned.

Seventeen-year-old Ken Russell dangled from the roof of a village church! Ken had lied about his age in order to join the army. In Normandy, he managed to free himself and jump twenty feet to the ground. Then he went into combat on his own against Germans firing at Allied planes. Later, he met up with more paratroopers to attack German gun sites.

Thousands of other troopers also landed alone and lost in the dark. The men were supposed to link up with their units as soon as they were on the ground. On D-Day, however, for most, this never happened. Instead, they joined up with men they’d never seen before. Or they fought alone. They fought Germans wherever they found them, inventing attack plans on the spot.

Lieutenant Richard “Dick” Winters, a paratrooper from a team called Easy Company, landed in the middle of nowhere without a gun. His rifle had been whipped away in the air. Winters unstrapped the knife from his ankle and set out to find the thirty-two men in his troop.

Suddenly figures loomed in the darkness ahead. Were they friend or foe? Winters snapped his “cricket.” It was a tiny clicker that troopers used to identify each other at night. He heard two clicks back: click-clack, click-clack. Good! That meant Allied troops. Luckily, Winters had found five men from his own troop, Easy Company.

Eventually, thirteen men of Easy Company linked up on D-Day. Their commander was missing. (He died when his plane exploded.) So Winters became their leader. The small force captured four big enemy cannons that were tearing up Utah Beach—even though the Germans guarding the tanks outnumbered them four to one.

The brave efforts of paratroopers met with other successes. German soldiers couldn’t make sense of the scattered attack “pattern,” and they failed to counterattack. Most important, the paratroopers seized key exit bridges and roads.

However, by the end of D-Day, the paratroopers had suffered a terrible toll. About one out of five was killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. As a result, the US military never had troops parachute in at night again.